Revista Electrónica Educare (Educare Electronic Journal) EISSN: 1409-4258 Vol. 24(3) SETIEMBRE-DICIEMBRE, 2020: 1-15

[Cierre de edición el 01 de Setiembre del 2020]

doi: https://doi.org/10.15359/ree.24-3.26

http://www.una.ac.cr/educare

educare@una.ac.cr

Quantifying Sentence Variety in English Learners

Cuantificación de la variedad de oraciones en aprendientes del inglés

Quantificando a variedade de frases em estudantes de inglês

William Charpentier-Jiménez

Universidad de Costa Rica

San José, Costa Rica

wcharpentier@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8554-7819

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8554-7819

Recibido • Received • Recebido: 22 / 01 / 2019

Corregido • Revised • Revisado: 29 / 07 / 2020

Aceptado • Accepted • Aprovado: 18 / 08 / 2020

Abstract: This article studies students’ use of sentence variety in an ESL writing course. The study includes three sentence features: (a) sentence types, (b) sentence combining, and (c) sentence patterns. Although sentence variety is part of the curriculum, the actual use of sentence structures has not been measured so far. By understanding students’ use of sentence structures, it is possible to propose valid curricular changes in the language program. This quantitative project has been carried out by analyzing 36 paragraphs written by students in the first writing course of a B.A. in English. The study included 433 sentences. Each sentence was examined individually. Data shows that 14.54% of the sentences presented a type of error. The types of errors included were the following: 12 fragments (2.77%), 29 fused sentences (6.69%), and 22 comma splices (5.08%). The remaining number of traditional sentences studied was 370 (85.45%). Results demonstrate that students favor certain types of structures and ignore others. Therefore, the demands of the curriculum and the written production of students lack coherence. Consequently, curricular changes must be incorporated to improve students’ written production.

Keywords: Written language; second language instruction; sentence variety; higher education.

Resumen: Este artículo estudia el uso de diferentes tipos de oraciones por parte de estudiantes de inglés como segunda lengua en un curso de escritura. El estudio incluye tres subdivisiones de las oraciones: (a) tipos de oración, (b) combinación de oraciones, y (c) patrones de oración. Aunque la variedad de oraciones es parte del currículo, el uso real de las estructuras no ha sido medido hasta el momento. Al comprender el uso de las estructuras por parte del estudianteado, es posible proponer cambios curriculares válidos en el programa de idiomas. Este proyecto cualitativo ha sido llevado a cabo al analizar 36 párrafos escritos por estudiantes que cursan su primer curso oral en un bachillerato en inglés. Cada oración ha sido examinada individualmente. Los resultados demuestran que 14.54% de las oraciones presenta algún tipo de error. Los tipos de error incluyen: 12 fragments (2.77%), 29 fused sentences (6.69%), y 22 comma splices (5.08%). El resto de las oraciones tradicionales analizadas fue de 370 (85.45%). Se demuestra que los estudiantes favorecen ciertos tipos de estructuras mientras ignoran otras. Por lo tanto, las demandas del currículo y la producción escrita del estudiantado carece de coherencia. Consecuentemente, se deben incorporar cambios curriculares para mejorar la producción escrita del estudiantado.

Palabras claves: Lenguaje escrito; enseñanza de una lengua extranjera; variedad de oraciones; educación superior.

Resumo: Este artigo estuda o uso da variedade de frases utilizadas por parte dos estudantes de inglês como segundo idioma, num curso de redação. O estudo inclui três subdivisões de uma frase: (a) tipos de frase, (b) combinação de frase e (c) padrões de frases. Apesar da variedade de frases ser parte do currículo, o uso real de estruturas de frases nunca foi medido até o momento. Ao entender o uso das estruturas de frases por parte dos estudantes, é possível propor alterações curriculares válidas no programa do idioma. Este projeto qualitativo foi realizado ao serem analisados 36 parágrafos escritos por estudantes que cursam pela primeira vez um curso oral num bacharelado em inglês. Cada frase foi examinada individualmente. Os resultados encontrados indicam que 14,54% das frases apresentaram um tipo de erro. Os tipos de erros incluídos foram: 12 fragmentos (2,77%), 29 sentenças condensadas (6,69%) e 22 vírgulas seguidas (5,08%). O número restante de frases tradicionais estudadas foi de 370 (85,45%). Estes resultados demonstram que os estudantes preferem certos tipos de estruturas e ignoram outras. Portanto, as demandas do currículo e a produção escrita dos estudantes carecem de coerência. Consequentemente, as mudanças curriculares devem ser incorporadas para melhorar a produção escrita dos estudantes.

Palavras-chave: Idioma escrito; ensino de um segundo idioma; variedade de frases; educação superior.

Introduction

Writing has become an essential skill in academic and work-related settings. Different from other skills, the process of writing may be less natural and arguably more difficult for some people, even for those who have learned the language in native contexts. Nosratinia and Razavi (2016, p. 1043) mention that “Writing is often considered as the most difficult skill to be mastered because of its complexity”. In addition, Tillema (2012, p. 1) argues that “Writing is one of the most important skills for educational success, but also one of the most complex skills to be mastered”. Part of this complexity derives from choosing the right vocabulary, developing an appropriate organization, and constructing clear and varied sentences. Sentence variety involves changing the length, structure, and kinds of sentences to avoid monotony, provide emphasis, and achieve different purposes (Henry, & Kindersley, 2017; Solikhah, 2017). For this reason, professors often guide students to include different kinds of sentences in their written work.

Several authors that have dealt with writing skills (Coombe et al., 2014; Reid, 2006; Sullivan, & Eggleston, 2006) include sentence variety as an important component of writing proficiency. Moreover, textbooks about writing skills generally include sections dedicated to certain types of sentence variety (Henry, & Kindersley, 2017; Hogue, 2007; Reid, 2001). When students engage with the subject matter through a variety of resources, they achieve the intended objectives and internatilze the given contents in a better way. Since educative curriculum materials reflect the academic content present in a language course or program, the guiding principle behind the inclusion of sentence variety in the language curriculum is to help students enrich their writing and engage their audience.

As mentioned before, textbook authors, as well as reference authors on the subject of writing, frequently emphasize the idea of sentence variety; however, this aspect has often been overlooked. On one hand, students may not see its importance because rubrics on writing relegate sentence variety as a secondary component of written production or do not include it at all (Green, 2001; Kelley, 2010; Penner, 2010). Professors frequently point out errors that students’ can easily perceive or offer advice on content and organization but not necessarily on sentence variety. When thinking about sentences, professors usually emphasize structure or organization, concepts that deal more with grammatical accuracy and punctuation than with the variety of sentences used. On the other hand, it is important to acknowledge that measuring sentence variety is not an easy task. In particular, no clear parameter of how many kinds of sentences or what distribution is ideal exists.

The purpose of this investigation is to quantify the number of sentence types students use when writing short compositions. Although its importance is clear, measuring sentence variety has not been fully integrated in the academic practice. In this research, sentences will be analyzed following three major kinds of classification (a) sentence combination, (b) sentence patterns, and (c) sentence types. The researcher considers that students may only improve their writing through a deep awareness of their strengths and weaknesses when writing. This can only be achieved through a systematic analysis of the kinds of sentences they use in their papers. A study of the present nature could increase this awareness and promote changes in students’ mindsets and academic practices.

Finally, the results of this study could induce the inclusion of sentence variety in scoring rubrics, self-assessment checklists, and peer-feedback checklists. In this way, students could become aware of their own production and improve their writing based on that feedback.

Literature Review

Quantifying sentence variety can be approached from different perspectives. As mentioned before, this study deals with three kinds of sentence constructions: (a) sentence combination, (b) sentence patterns, and (c) sentence types. These names are given for convenience in order to distinguish one form from the other. Nevertheless, it is possible that one kind of sentence may overlap into the others. Additionally, textbook writers do not consistently label these kinds of sentence structures in the same way. In order to avoid ambiguity, the following paragraphs describe the characteristics of each kind of construction.

Sentence combination is perhaps the most common kind of sentence structure found in writing books (Altman et al., 2018; Although most books describe them in similar ways, the descriptions given here follow what students learn during their major. For combining ideas include embedding different sentences into one by using compound verbs, compound nouns, or participial phrases. Although these structures are important when writing, sentence combination is defined in this research as those sentences that belong to each of the four categories: simple (consisting of only one clause), compound (consisting of two or more independent clauses), complex (formed by at least one independent clause plus at least one dependent clause), and compound-complex sentences (made from two independent clauses and one or more dependent clauses).

Along with sentence combination, sentence patterns have often been analyzed in different ways (Flores Mora et al., 2002; Hauschild, 2013; Kolln, & Funk, 2011). Kolln and Funk (2011) define sentence patterns as the “underlying skeletal structure of almost all the possible grammatical sentences” (p. 28). According to them, “ten such patterns will account for almost all the possible sentences of English” (p. 28). The main problem with this definition, however, is that grammarians have not often agreed on the number of patterns present in English. Kolln and Funk (2011) note that “this list of patterns is not the only way to organize the verb classes: Some descriptions include fifteen or more patterns” (p. 29). Other books often included seven patterns (Flores et al., 2002; Nichols, 1965), or even four patterns (Dee Richeson, 2015). As mentioned before, this study focuses on what students will find in the curriculum. Therefore, the analysis conducted in this paper will reflect the description provided by Kolln and Funk (2011). This list of patterns can be summarized as follows:

“Pattern I. NP1 + V-be + ADV/TP”: The musicians are here.

“Pattern II. NP1 + V-be + ADJ”: The players were happy.

“Pattern III. NP1 + V-be + NP1”: Alonso is a famous artist.

“Pattern IV. NP1 + LV + ADJ”: They seem nice.

“Pattern V. NP1 + LV + NP1”: The chairperson called off the meeting.

“Pattern VI. NP1 + V-int”: The baby was sleeping.

“Pattern VII. NP1 + V-tr + NP2”: The firefighters rescued the cat.

“Pattern VIII. NP1 + V-tr + NP2 + NP3”: I sent flowers to Laura.

“Pattern IX. NP1 + V-tr + NP2 + ADJ”: The jury found them guilty.

“Pattern X. NP1 + V-tr + NP2 + NP2”: They elected her president. (Kolln, & Funk, 2011, p. 30)

Sentences that include fronting, passive voice, or other transformations will be analyzed according to their underlying sentence pattern. When sentences contain a compound verb, they will be treated as separate sentences.

The term sentence types describes sentences that fall under four different categories: declarative, interrogative, imperative, or exclamatory sentences (Kolln, & Funk, 2011; Swick, 2009). According to Kolln and Funk (2011), speakers alter the basic sentence patterns described above to state a fact or opinion, give commands, express strong feelings, or ask questions. Each sentence type has particular features:

Declarative sentences: They are used to state a fact or an opinion. Each sentence follows a subject plus predicate structure. Compared to the other sentence types, these sentences are not altered; they follow exactly the same structures of sentence patterns. An example of a declarative sentence is The day is lovely.

Interrogative sentences: They are used to ask questions. They are often divided into yes/no and wh or interrogative questions. Yes/no questions alter the structure by inverting the verb and the subject (e.g. Are you home?) or by placing an auxiliary before the subject (e.g. Did you like it?). In turn, wh or interrogative questions alter the formula by substituting the noun phrase object, noun phrase subject complement, determiners, or adverbials with an interrogative word (What do you want?, Where is she?). In these cases, we either insert an auxiliary or shift the elements in the sentence accordingly. When substituting the noun phrase, subject slot with an interrogative word (Who is there?), the order subject plus predicate remains.

Imperative sentences: Their purpose is to give a command. In each sentence of this kind, the subject is not stated, but it is clearly implicit in the sentence. Some examples of imperative sentences are Go and Do it right now. These types of sentences are more often found in casual speech than in writing.

Exclamatory sentences: This type of sentences is used to place particular emphasis on a part of the sentence. Kolln and Funk (2011) state that “a formal exclamatory sentence involves a shift in word order that focuses special attention on a complement” (p. 100). Examples of exclamatory sentences are What an honest man you are! and How intelligent she is!

Because this category is rather short and their construction is tightly linked to their use, it is expected that students’ writing incorporates declarative sentences more than any other type of sentence in this group.

The present study also takes into account faulty sentence constructions. Fragments, comma splices, and fused sentences (also known as run-on sentences) are the main types of faulty constructions that students are asked to avoid (Brannan, 2010; Hacker, 2009; Henry, & Kindersley, 2017). When defining these terms, experts consistently follow the same criteria. Henry and Kindersley (2017), for example, define fragment as an incomplete thought idea, a comma splice as using a comma to link two sentences, and a and a fused sentence as a lack of punctuation between sentences. Since the purpose of this paper is to quantify sentence variety, faulty sentence constructions will be taken into account to reflect students’ actual language production.

This article has a different standpoint from other studies because it seeks to measure sentence variety from various perspectives. Most of the research consulted dealt with one kind of sentence variety only. Saddler (2002), for example, examined “the effects of sentence combining practice on skilled fourth-grade writers who have average sentence combining ability and less skilled fourth-grade writers who have below average skills in sentence combining” (p. 1). This study included forty-three students who were randomly assigned to two different groups. The experimental group learned sentence combining skills, specifically writing compound sentences, and the comparison group concentrated on grammar skills that sought to increase their vocabulary. In order to measure sentence combining skills, the study included the TOWL-3, a Sentence Combining subtest, and an oral sentence combining probe, among other tests. The main findings of the study suggested that sentence combining instruction improved students’ sentence combining skills in their oral and written production. In addition, data indicated that peer-assisted methods to organize instruction prove beneficial during instruction. Although the present study does not intend to analyze students’ writing improvement, identifying the kinds of sentences students use would provide clear indicators as to what kinds of sentences need reinforcement. On the other hand, using peer-assisted methods during instruction clearly serves to improve sentence variety, and this idea could be expanded to the various kinds of sentences proposed in this paper.

In a different study, Jenkins (2000) explored whether gender influenced students’ production of simple and complex sentences. In order to accomplish this, the researcher analyzed students’ classification essays and cause/effect essays. Subjects were both female and male students taking the first year in a developmental writing course. The study examined gender preferences in terms of sentence combination use as well as types and frequency of errors made with complex sentences. Results indicated that sentence variety did not change due to gender or writing task type. Data also pointed out that fused sentences, in the case of women, and verb-tense consistency, in the case of men, were the main types of mistakes found in students’ essays. Nevertheless, Jenkins (2000) mentioned that gender differences are not as marked as other previous studies have suggested. This study indicated that gender does not really affect sentence construction. Based on the results of the present study, however, it would be possible to recommend further research to explore if other characteristics, such as age, level, or background knowledge influence students preferences in sentence construction or types of errors.

Wood and Struc (2013) conducted a study on writing that included complexity, fluency, sentence variety, and sentence development. The purpose of the study was to “use a suite of 12 metrics to examine, describe and compare evidence of syntactic complexity, fluency, sentence variety, and sentence development” (p. 11). In terms of sentence variety, the writers examined narrative and argumentative texts written by 22 L2 learners at a university in Japan. This longitudinal study was conducted during the first weeks of students’ first, second, and third years. Sentence variety was measured through a statistically-based Sentence Variety Index (SVI). The index ranged “from 0 to 100, 0 indicating no variety (i.e., all sentences of one type) and 100 indicating maximum variety (i.e., all four sentence types equally represented)” (p. 13). In narrative writing samples, simple sentences comprise the majority of sentence types, but their number decreases while complex, compound, and compound-complex sentences increase through time. In argumentative writing samples, simple sentences also account for the majority of sentences, but their use only decreases during students’ second year and levels up during their third year. Complex, compound, and compound-complex sentences in argumentative writing samples increased during the second year. The first and third sample showed similar results for these kinds of sentences. These data suggest that level and instruction influence how students structure sentences. Quantifying sentence kinds through time can demonstrate if students use a wider variety of structures depending on the genre they are writing about or their level.

Sentence variety has also gained importance as a means to improve students’ writing in L2 settings. Solikhah (2017) “[studied the] … difference of corrections on grammar, sentence variety, and developing details to improve the quality of the essay by Indonesian learners” (p. 116) as well as the individual impact of each type of correction in students’ writing. In this paper, sentence variety included sentence combination only. This study included 66 students taking a research course in the English department of a university in Indonesia. Students were divided into three groups. The treatment consisted of a three-step procedure. First, students’ drafts were corrected throughout the course; the final product was an expository, 1,000 to 1,500 word-long essay. As a second step, each student discussed the results of their meetings with their thesis advisors. Finally, a set of drills focusing on grammar correction, sentence variety, and developing details was created for each treatment group. In order to gather the necessary data, student’s final essays were graded by 9 raters. Solikhah (2017) concludes that “contribution of each treatment was respectively as follows: sentence variety (58.5%), developing details (46.5%), and grammar (38.6%). Evidently, sentence variety is the most dominant technique to improve the quality of the essay up to 58.5%” (p. 125). These data prove the need for clear guidelines to treat sentence variety. A first step, however, should be to quantify the kinds of sentences students use and then concentrate on those structures that are less used.

As can be seen, experts often approach sentence variety from different perspectives. Sentence combination stands out as the most common kind of variety present in the literature. Some research on sentence variety concentrates on how instruction can help improve students’ writing. Other studies analyze students’ preferences in sentence construction. Finally, some writers have explored quantifying sentence variety in students’ papers. Nevertheless, all efforts for measuring sentence kinds have focused on one segment of sentence variety. The present study seeks to determine the number and kind of sentences students use in a broader sense in order to suggest changes to the current writing curriculum.

Method

Participants

A personal electronic mailing list of 36 sophomores taking the first writing course from the B.A. in English and B.A. in English Teaching was created. The list consisted of students who were taking the course for the first time and agreed to participate in the study. All students are learning English as a foreign language in a non-immersive language program.

Materials

A written consent document was created and distributed among the students encouraging them to participate. The texts to analyze consisted of students’ final paragraph. The topic of the paragraphs was free, but it had to follow a comparison and contrast rhetorical pattern. The number of sentences included in the study added up to 433.

Procedure

This study used a quantitative design. The researcher asked for permission to attend a class and ask students for their participation. After briefly explaining the nature of the study, students were given a written consent. The researcher instructed them to read it, asked any questions they considered necessary, and requested to sign it if they wished to participate. After collecting all the consents, a list of 36 participants was created. Students who agreed to participate provided an electronic copy of the final, in-class paragraph to the researcher. Students’ paragraphs were combined in a single document. All titles were deleted since they do not necessarily follow the structure of a sentence. All sentences were divided and arranged following the traditional definition of sentence: a structure that starts with a capital letter and ends with a period. After this, each individual sentence was analyzed according to their structure: (a) sentence combination, (b) sentence pattern, and (c) sentence type. Faulty sentences were also classified but were kept from any structural analysis.

Analysis of the Results

The following description and analysis synthesize students’ sentence use in their final paragraphs. Of the 36 students who participated, an equal number of paragraphs was analyzed. A total of 433 (100%) traditional sentences was examined. Traditional sentence here refers to sentences that start with a capital letter and end with a period. Nevertheless, it was concluded that 63 sentences (14.54%) presented a type of error. The source of error for those sentences can be divided in: 12 fragments (2.77%), 29 fused sentences (6.69%), and 22 comma splices (5.08%). The remaining number of traditional sentences studied was 370 (85.45%). Since the present analysis includes three ways to address the umbrella term sentence, some of the totals may show variations. For example, from the perspective of combinations, the same number of traditional sentences was analyzed (370); however, from the perspective of sentence type and sentence pattern analyses, results tend to be higher since each verb used in the main clauses, including compound verbs, was considered.

In writing courses, and this one is no exception, students are asked to add sentence variety to their written work. To explore the amount of sentence variety, three subsets of the sentence structures were analyzed. First, 370 structures were studied in terms of their sentence combining structure. As can be seen from Table 1, students tend to favor simple sentences while the use of more elaborate constructions decreases. Although it is impossible to establish what an appropriate balance would be, complex, compound, and compound-complex sentences together represent less than 50% of the total of correct sentences written by students. Additionally, only three sentences followed a compound-complex pattern. Considering that students are specifically instructed to add sentence variety, this structure remains below any permissible level in a composition course of this nature.

Table 1: Grouped Frequency Distribution of Sentence Combinations

Note: Compiled by author based on data gathered through students’ written work.

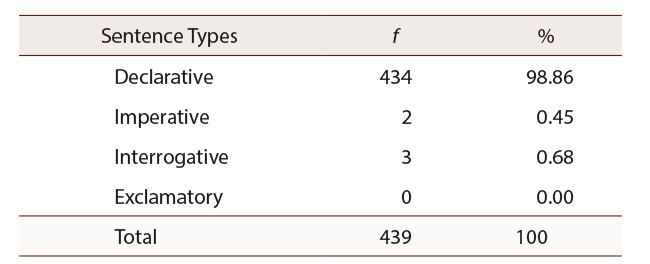

The distribution of sentence types shows a more dissimilar arrangement. Table 2 illustrates this distribution. On one hand, of all the sentences analyzed, students’ written production shows a greater use of declarative sentences compared to any other type of sentence. Nevertheless, this disparity may fall under normal parameters taking into account that imperative, interrogative, and exclamatory sentences serve very specific purposes that students may not have had the need to use. On the other hand, these results demonstrate that students’ written work cannot be considered a valid source to know if students are proficient when writing imperative, interrogative, and exclamatory sentences. Because of the nature of their paragraphs, students could avoid writing or may not find it necessary to write any other type of sentence besides declarative ones. Furthermore, they could purposely avoid those constructions that they have not mastered or find more difficult to use, as may be the case for exclamatory sentences.

Table 2: Grouped Frequency Distribution of Sentence Types

Note: Compiled by author based on data gathered through students’ written work.

The last subset of structures encompasses those of the sentence patterns. This writing course, however, does not explore the idea of sentence patterns for writing per se. The domain of sentence patterns is studied parallel to the writing course but in grammar courses. Nonetheless, students are advised to vary the types of verbs used and to avoid, as much as possible, the repetition of the verb to be as the verbal of the main clause. Considering this, Table 3 shows that almost half of the patterns used belong to pattern VII. Pattern VII is indeed one of the most common patterns in the language because of the number of verbs that can fall under this category (all transitive verbs) and their relative common use, a subject interacting with a single object. However, the rest of the patterns where transitive verbs are needed fall below 3% in terms of usage. Even smaller is the number of patterns IV and V. Patterns IV and V include linking verbals besides be verbals. These two patterns do not account for even 2% of the total number of sentences analyzed. Finally, those patterns where be is used account for more than 30% of all structures used. It is clear, however, that the figure is obtained from three patterns. Still, after pattern VII and VI, patterns II, III, and I respectively are the most used.

Table 3: Grouped Frequency Distribution of Sentence Patterns

Note: Compiled by author based on data gathered through students’ written work

It is important to mention that these data should not be taken lightly. Since the main purpose of this study was to measure sentence variety, a deeper analysis should be carried out to generalize the results presented here.

Discussion

More than any other skill, writing is perhaps the most difficult one to master. Vocabulary, spelling, punctuation, and structure are just some of the many features students must deal with when writing. Sentence variety remains secondary to most language learning settings. In some cases, this aspect is mentioned and studied, but it is not often evaluated or followed up. Abdullah et al. (2019, p. 89) mention that absence of “sentence variety is certainly not the only problem faced by ESL students, but to add to this predicament, they also lack native speaker’s intuition about what sounds right, and they may just be unaware of the monotonous nature of their writing”.

In this sense, data also indicates that 14.54% of the sentences analyzed included at least one type of structural error. This evidences that, by the end of the course, some students are not capable of writing error-free structures, despite the topics being directly addressed in the said course. Rubrics where fragments, fused sentences, and comma splices are directly evaluated seems a feasible solution. Such evaluation can have a formative, self or peer assessment format at the beginning of the course and a more summative assessment as the course advances. In addition, extra practice and video tutorials could be included for those students who struggle with some types of errors without slowing down those students who show proficiency in terms of punctuation.

Additionally, the data derived from this project reflects that students do not consistently use complex, compound, or compound-complex sentences. Some possible reasons that explain this phenomenon are that students do not see the need to use those sentence combining structures or that they do not feel they are ready to use them yet. What students may need at this stage is more guidance, where the teacher, as an editor, advises students when to use or not to use a particular combination. A plausible solution would be to ask students to incorporate combinations in their rewrites after they have raised some awareness on the structures they have been using and the reasons why varying them would improve their writing.

When examining the distribution of sentence types, it is evident that students mostly use declarative sentences. Although it is true that declarative sentences account for a majority of the structures used in writing, this also means that students could successfully complete the course without having to write imperative, interrogative, or exclamatory sentences. Nevertheless, as second language learners, students are instructed to use those sentences. Different from sentence combining, it is less advisable to ask students to write using different sentence types since their use depends on the needs of the writer. Therefore, what is necessary is to incorporate an alternative way to evaluate these structures. Composition alone, be it of paragraphs or essays, proves inefficient to demonstrate mastery of sentence type structures.

In terms of sentence patterns, the distribution may be considered somewhat normal due to the number of transitive verbs and the idea that pattern VII conveys. Nonetheless, the distribution shows a high use of be verb patterns. This poses certain questions that need to be answered in order to modify teaching practices: Are these patterns strictly necessary to convey what students wanted? Do students use these structures because they are simpler? Is it possible for students to express the same idea using other verbs? How can instruction be improved so that students raise awareness and stop relying on be verb patterns? By answering these questions, instructors can develop adequate strategies to determine which writing structures need more attention. The rewrite stage could be a phase that students dedicate to finding all be verb patterns in their own writing. During this part of the writing process, together with other peers and the instructor, students would be asked to revise those sentences and try to replace be verbs when possible.

Conclusion

Clearly, no one single teaching practice brings reform to writing instruction. However, the ideas presented here provide a structure within which small changes gather and flow together to become the substance of new curricular changes and teaching practices. However, in order to establish a true transformation, further research is required to determine the general needs of the population and the particular aspects of sentence construction in an ESL setting. Research about the use of sentence structures by advanced students in the program should also be conducted. This will allow comparing and contrasting the amount of variety and how or if students improve over the years. Finally, research should also strive for evaluating this and any other proposals derived from the present study.

Recommendations

The importance of teaching sentence variety properly offers several benefits. First, students’ writing will become more vivid and interesting. The result may be a more cohesive and coherent production on the part of students. Second, students will gain a set of structures that will facilitate the expression of their ideas in a better, clearer way. They may be avoiding structures not because they want to but because they do not know how to use them. Additionally, this may hinder their production and make them sound less natural. Finally, students will be able to critically analyze their own work and that of their classmates and other writers in general. By doing this, they would learn to imitate better practices and writing patterns to improve their writing.

By finding out what kinds of sentence students use and quantifying them, a study of this nature will benefit not only the curriculum but also students in general. First, writing courses could include clear guidelines and policies on how to treat sentence variety. In this way, professors would have a clear set of procedures in order to evaluate and guide students to include different kinds of sentences. A second benefit would derive from including sentence variety as part of calibration sessions. Calibration sessions are meetings where professors grade papers, in the case of writing, to standardize criteria, procedures, and marking. Coombe et al. (2014) argue that although calibration sessions are not popular among professors and tend to be time-consuming, they are essential to achieving standard procedures. Nevertheless, since no clear guidelines about sentence variety exist, the topic remains excluded from calibration sessions.

Declaración de Material complementario

Este artículo tiene disponible como material complementario:

- La versión preprint del artículo en https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3365374

References

Abdullah, L., Kassim, R., Ghani, N. A. A., Rahman, H. A., & Zamin, A. A. M. (2019). Enhancing ESL writing using sentence variety checklist. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 9(13), 87-95. 10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i13/6244

Altman, P., Caro, M., Metge-Egan, L., Roberts, L., & Wilson, P. (2018). Sentence-Combining workbook (5th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Brannan, B. (2010). A writer’s workshop: Crafting sentences, building paragraphs. McGraw-Hill.

Coombe, C., Folse, K., & Hubley, N. (2014). A practical guide to assessing english language learners. University of Michigan.

Dee Richeson, S. (2015). Sentence structure: The key to english usage, grammar and punctuation. CreateSpace.

Flores Mora, B., Alfaro Murillo, V., &Flores Mora, M. A.(2002). Basic english syntax. Editorial UCR.

Green, K. A. (2001). Correlation of factors related to writing behaviors and student -developed rubrics on writing performance and pedagogy in ninth-grade students (Publication No. 304723157). [Doctoral dissertation, University of Southern California, United States]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Hacker, D. (2009). Rules for writers (6th ed.). Bedfordf/St. Martin’s.

Hauschild, K. (2013). English sentence patterns. Beau Monde Language Services.

Henry, D. J., & Kindersley, D. (2017). Writing for life: Paragraphs and essays (4th ed.). Pearson.

Hogue, A. (2007). First steps in academic writing (2nd ed.) Pearson-Longman.

Jenkins, P. A. (2000). Linguistic differences between male and female developmental writers (Publication No. 304670190). [Doctoral dissertation, Tennessee State University, United States]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Kelley, K. (2010). A critical examination of rubric use for evaluating individual writing assignments in the undergraduate classroom (Publication No. 1480134). [Doctoral dissertation, Western Illinois University, United States]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Kolln, M., & Funk, R. (2011). Understanding english grammar (9th ed.). Longman.

Nichols, A. E. (1965). English syntax. Advanced composition for non-native speakers. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Nosratinia, M., & Razavi, F. (2016). Writing complexity, accuracy, and fluency among EFL learners: Inspecting their interaction with learners’ degree of creativity. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 6(5), 1043-1052. https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0605.19

Penner, I. S. (2010). Comparison of effects of cognitive level and quality writing assessment (CLAQWA) rubric on freshman college student writing (Publication No. 3433058). [Doctoral dissertation, Liberty University, United States]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Reid, J. M. (2001). The process of composition (3ra ed.). Longman.

Reid, J. M. (2006). Essentials of teaching academic writing. Heinle Cengage Learning.

Saddler, B. (2002). An analysis of the effects of sentence combining practice on the writing of students with above- and below-average sentence combining skills (Publication No. 3078214). [Doctoral dissertation, University of Maryland, United States]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Solikhah, I. (2017). Correction on grammar, sentence variety and developing detail to qualify academic essay of indonesian learners. Dinamika Ilmu, 17(1), 115-129. https://doi.org/10.21093/di.v17i1.783

Sullivan, K. D., & Eggleston, M. (2006). The McGraw-Hill desk reference for editors, writers, and proofreaders. McGraw-Hill.

Swick, E. (2009). Practice makes perfect. English sentence builder. McGraw-Hill.

Tillema, M. (2012). Writing in first and second language: Empirical studies on text quality and writing processes [Doctoral thesis]. Utrecht University, Netherlands. https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/241028

Wade, P. (2014). Sentence craft: A sentence-combining handbook paperback. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Wood, N., & Struc, N. (2013). A corpus-based, longitudinal study of syntactic complexity, fluency, sentence variety, and sentence development in L2 genre writing. Reitaku University Journal, 96, 1- 44.

Artículo de la Revista Electrónica Educare de la Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica by Universidad Nacional is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Costa Rica License.

Based on a work at https://www.revistas.una.ac.cr/index.php/EDUCARE

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at educare@una.cr