Revista Electrónica Educare (Educare Electronic Journal) EISSN: 1409-4258 Vol. 26(2) MAYO-AGOSTO, 2022: 1-21

doi: https://doi.org/10.15359/ree.26-2.28

https://www.revistas.una.ac.cr/index.php/educare

educare@una.ac.cr

[Cierre de edición el 01 de Mayo del 2022]

Promoting the Development of Intercultural Competence in Higher Education Through Intercultural Learning Interventions

El desarrollo de la competencia intercultural en educación superior mediante intervenciones de aprendizaje intercultural

Promovendo o desenvolvimento da competência intercultural no ensino superior através das intervenções na aprendizagem intercultural

María Luisa Sierra-Huedo

Universidad San Jorge

Villanueva de Gállego, España

mlsierra@usj.es

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8809-7924

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8809-7924

Almudena Nevado-Llopis

Universidad San Jorge

Villanueva de Gállego, España

anevado@usj.es

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4366-8804

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4366-8804

Recibido • Received • Recebido: 09 / 06 / 2020

Corregido • Revised • Revisado: 14 / 03 / 2022

Aceptado • Accepted • Aprovado: 18 / 04 / 2022

Abstract:

Introduction. This article analyses the impact of an intercultural learning intervention in a Spanish university post-European Higher Education Area implementation. Objective. Our research’s main objective consisted of measuring the development of intercultural competence in the first cohort of a Translation and Intercultural Communication bachelor’s degree in a Spanish university, before and after taking specific courses in intercultural studies and spending a study abroad semester. Methodology. A mixed methodology was implemented, in which the Intercultural Development Inventory (IDI) was used as a measuring instrument. Additionally, in-depth personal interviews were conducted to complement the data obtained. Results. The results of this study show that the programming and sequencing of specific courses, together with experiences abroad, contribute to the development of intercultural competence. Conclusions. More intercultural learning interventions are needed in higher education courses to develop and build an intercultural campus and educate global citizens. When applying intercultural learning interventions and intercultural methodologies, students develop their intercultural competence, a key competence for 21st-century graduates.

Keywords: Intercultural competence; intercultural learning intervention; study abroad; intercultural development inventory; higher education; global citizen.

Resumen:

Introducción. Este artículo analiza el impacto de una intervención de aprendizaje intercultural en una universidad española, tras la implantación del Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior. Objetivo. El principal objetivo de esta investigación consistía en medir el desarrollo de la competencia intercultural en la primera promoción del Grado en Traducción y Comunicación Intercultural de una universidad española, antes y después de haber cursado asignaturas específicas relacionadas con los estudios interculturales y haber llevado a cabo una estancia en el extranjero de un semestre. Metodología. Se empleó una metodología mixta, cuya técnica principal fue el inventario de desarrollo intercultural (IDI). Además, se llevaron a cabo entrevistas personales en profundidad para complementar los datos obtenidos. Análisis de resultados. Los resultados del estudio muestran que la programación y secuenciación de cursos específicos, junto con las experiencias en el extranjero, contribuyen al desarrollo de la competencia intercultural. Conclusiones. Son necesarias más intervenciones de aprendizaje intercultural en los cursos de educación superior para desarrollar y construir campus interculturales y educar a una ciudadanía global. Cuando se emplean intervenciones de aprendizaje y metodologías interculturales, el estudiantado desarrolla su competencia intercultural, una competencia fundamental para las personas graduadas del siglo XXI.

Palabras claves: Competencia intercultural; intervención de aprendizaje intercultural; estancia en el extranjero; inventario de desarrollo intercultural; educación superior; ciudadano global.

Resumo:

Introdução. Este artigo analisa o impacto da intervenção de aprendizagem intercultural na Universidade da Espanha após implementação do Espaço Europeu Do Ensino Superior. Objetivo. O principal objetivo da nossa pesquisa consiste em medir o desenvolvimento de competência intercultural na primeira coorte de um bacharelado em Tradução e Comunicação Intercultural em uma universidade espanhola em estudos interculturais durante um semestre no exterior. Metodologia. Foi seguido um método de mistura, cujo instrumento de medição era o Inventário do Desenvolvimento Intercultural (IDI). Além disso, entrevistas pessoais em profundidade foram conduzidas para complementar os dados obtidos. Resultados. Os resultados deste estudo mostraram que a programação e sequenciamento de curso específico, juntamente com experiências no exterior, contribuem para o desenvolvimento de competências interculturais. Conclusão. São necessárias mais intervenções de aprendizagem intercultural nos cursos de educação superior para desenvolver e construir campus intercultural e educar os cidadãos globais. Quando se implementam intervenções de aprendizagem e metodologias interculturais, os estudantes desenvolvem sua competência intercultural, uma competência fundamental para os graduados do século XXI.

Palavras-chave: Competência intercultural; intervenção de aprendizagem intercultural; estudo no exterior; inventário do desenvolvimento intercultural; ensino superior; cidadão global.

Introduction

The acquisition and development of intercultural competence are major desired outcomes for university students. This competence is one of the most important for college graduates to be successful in their working environments. The European Higher Education Area (EHEA) as well as study abroad programs such as ERASMUS + claim to promote this competence. Indeed, there are many programs that “refer to the importance of cultural learning and more recently intercultural competence, but there is still a lack of good practice” (Byram et al., 2001, p. 1), and it remains unclear how teachers/trainers can help their students to acquire and develop intercultural competence.

Study purpose and research questions

The main purpose of this study is to demonstrate how planned and internationalized courses, together with study abroad programs, can promote the development of intercultural competence in students and therefore can help them become global citizens. In particular, the following research questions are addressed:

1. Are intercultural learning interventions in higher education degree programs, such as courses on Intercultural Communication and Intercultural Mediation, promoting the development of intercultural competence?

2. Do students who participate in both intercultural learning interventions and study abroad programs increase their intercultural competence?

3. How intercultural learning interventions help educate global citizens?

State of the art

Twenty first century higher education institutions claim to educate future graduates as global citizens. However, there are no learning outcomes associated with such a claim. Universities create internationalization processes and programs, mainly based on study abroad assuming that through those programs, the participating students will become interculturally competent (Cressy, 2021). Intercultural competence (IC) and its development are seen as one of the key competences that future university graduates should acquire during their college years. However, there is still some disagreement about what it is and how to assess it and in which way it is the correct way of doing it. The first challenge is to define the concept, since IC is referred to in more than 20 different ways in the literature: international competence, global competence, global citizenship, intercultural sensitivity, cross- cultural competence and multicultural competence to name just a few. Deardorff (2006) standardized a research-based definition of the concept (see below). According to Deardorff (2014) IC is a very complex, broad learning objective, which in order to cover all aspects of it and measure it, must be divided into various learning outcomes including behavioral and communication skills. To be able to measure IC, cognitive knowledge is needed as well as experience in an intercultural context or interaction. This can be achieved through study abroad or service-learning programs (Deardorff, 2014; Prieto-Flores et al., 2016). Although, there are studies that show how those intercultural experiences alone do not increase the development of IC, and that intercultural interventions, as well as guided reflections are mostly needed (Cressy, 2021; Engle & Engle, 2012; Vande Berg et al., 2009). The final important characteristic of IC is understanding that it is acquired through an intentional and developmental process that may take an entire life (Deardorff, 2014; Witte & Harden, 2021).

Theoretical models started to be developed in the 1970s and 1980s in the Western world, the USA, the UK and the Netherlands. There are a great variety of them, that measure different spectrums of IC. The three most popular are the Milton Bennett’s Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS), Hofstede’s model based on difference on cultural patterns (individualistic versus collectivistic societies), and Byram’s Multimodal Model of Intercultural Competence (Hernández-Moreno, 2021). Byram´s model focuses on certain sub-topics of IC such as empathy and respect for the other, and most of his research is based on language acquisition. In contrast, Bennett´s DMIS is based on a developmental perspective of how to acquire IC, and how to understand cultural differences (Hammer, 2015; Hernández-Moreno, 2021).

The next challenge is the assessment of IC. There are currently over 140 instruments to measure IC (Deardorff, 2014). A lot of research has been carried out to explore the assessment tools (see Fantini, 2009 in The Sage Handbook of intercultural Competence, among some of the most important reviews of IC tools). Some models are linked to certain tools like the case of Bennett DMIS (1993) and the Intercultural Development Inventory (IDI) (Hammer, 2015). Some key aspects of IC assessment have been researched previously, stressing that IC assessment should be done using a multi-method approach focusing more on the process than on the final outcome (Cressy, 2021; Deardorff, 2014). Measuring only the experience should not be considered sufficient. Intercultural training is seen as a must as well as guided reflection about those intercultural encounters. The use of the IDI to assess study abroad programs and experiences are common in the USA and some European countries. However, there is a lack of research in this area in the Spanish context. There are two important research studies, one using the IDI to measure study abroad programs (Rodríguez-Izquierdo, 2022) and to evaluate IC in service-learning programs (Prieto-Flores et al., 2016). There is no research into assessment of study abroad programs with intercultural training interventions and guided reflections in Spanish higher education.

Contextual and conceptual delimitation of the study

The research questions are based on the theoretical framework Bennett’s (1993) DMIS, because it focuses on the different ways that individuals “engage cultural difference in more holistic, sense-making/sense action frameworks” (Hammer, 2015, p. 13). Bennett’s Model identifies individuals whose culture is central in understanding their reality and then how they might develop into experiencing one’s culture in the context of other cultures. The DMIS guided the selection, planning and unit order of our course’s materials and activities, since it is one of the most constructivist-grounded approaches and our courses were taught following social constructivist methodology. The constructivist perspective implies that just exposure to difference is not enough; we create our own knowing and meaning actively involved, since learning is an active process that comes primarily from experience.

This study focuses on the first cohort of students in the degree in Translation and Intercultural Communication offered at a Spanish university post EHEA implementation. This empirical research is framed in a School of Communication and Social Sciences, in a university which was one of the firsts to implement the Bologna process in Spain. In order to answer the research questions, the researchers measured participants’ intercultural competence before and after taking specific courses on Intercultural Communication and Intercultural Mediation and spending a compulsory one-semester study abroad program.

Main assumptions

We think that sending students abroad alone does not increase their intercultural competence unless there are intercultural interventions, since “cultural contact does not necessarily lead to competence” (Bennett, 2008, p. 17). We also believe that courses such as Intercultural Communication or Intercultural Mediation should be part of the core programs of new degree programs under the EHEA if we really want our students to be interculturally competent when they graduate from university.

Additionally, we assume that the participants in this study, as third-year students in a Translation and Intercultural Communication degree, had previously acquired some skills, abilities and attitudes related to intercultural competence. Their desire to study and major in Translation indicates that they were previously interested in languages and cultures and probably had prior experience of travelling abroad. They had also previously taken courses in foreign languages and cultures, which to an extent, may have started to foster their intercultural sensitivity. The willingness to learn from different languages and cultures was present in the participants of the study.

Definitions of key terms

The main key terms related to this study are: intercultural competence (IC) and intercultural interventions (II). The first term is a very complex construct and there has been no agreement on how it should be defined. For the purpose of this study, we understand IC as the ability to behave and communicate “effectively and appropriately in intercultural situations based on one’s intercultural knowledge, skills and attitudes” (Deardorff, 2004, as cite in Deardoff, 2006, pp. 247-248). It involves “knowledge of others; knowledge of self; skills to interpret and relate; skills to discover and/or to interact; valuing others’ values, beliefs, and behaviors; and relativizing one’s self. Linguistic competence plays a key role” (Byram, 1997, p. 34, cited in Deardorff, 2006, p. 247). Finally, it should be recognized that the acquisition of IC is an ongoing process of development.

As for II, they are defined as the “intentional and deliberate pedagogical approaches, activated throughout the study abroad cycle (before, during, and after), that are designed to enhance students’ intercultural competence” (Paige & Vande Berg, 2012, pp. 29-30).

Study Context

International context

One of the main objectives pursued by the EHEA is to develop in European university graduates the ability to behave as interculturally competent citizens. This is evident in the Tuning Project, created to establish a consensus in European degree structures following the implementation of the Bologna process. This project includes the appreciation of diversity and multicultural issues, the ability to work in an international context, and the understanding of cultures and customs from other countries among the generic competences of the new degree programs.

As maintained by several authors (Mirzoyeva & Syurmen, 2016; Olk, 2009; Tomozeiu et al., 2016; Yarosh, 2012), the development of IC is accorded more importance in those majoring in Translation degree programs, as their work demands that they should be able to identify, know and understand their own and others’ cultural patterns, in order to socialize and work in multicultural settings and to act as cultural bridges, promoting understanding, key characteristics of an interculturally competent person.

National context

In the Spanish educational system, the Spanish National Agency for Quality Evaluation and Accreditation (ANECA) published a Libro Blanco del Título de Grado en Traducción e Interpretación (2004) [White Paper for Translation and Interpretation Degree Programs] which establishes some recommendations regarding generic and specific competences that need to be developed according to the configuration of current societies and their needs. In terms of generic competences, diversity and multicultural awareness, the ability to work in an international context, and knowledge of others’ cultures and customs are highlighted. Regarding the specific competences of the discipline, the ability to relate to other human beings, common knowledge about people and civilizations, and sociolinguistic competence are deemed important (Agencia Nacional de Evaluación de la Calidad y Acreditación, 2004).

Local and institutional contexts

This research focused on the first cohort of students in the degree in Translation and Intercultural Communication offered at a Spanish private university. This university was the only Spanish University to be created at the same time as the implementation of the Bologna Process.

The mentioned degree was established 14 years ago and presents a new approach to the area of Translation, with the introduction in its title of the nomenclature Intercultural Communication, which demonstrates the relevance of communication between people from different cultural backgrounds and, therefore, the importance of developing IC. This is the reason why the degree includes in its program a compulsory semester abroad during the fourth year and some courses, such as Intercultural Communication and Intercultural Mediation, that are aimed at helping students develop IC (Universidad San Jorge, n.d.). Conducting the research with the first cohort allowed us to understand what kind of new methods and training resources could be included in the two mentioned courses to enhance the students’ intercultural mindsets.

Theoretical framework

This study is grounded in Bennett’s (1993) DMIS conceptual framework. Discrepancies continue to exist in the contemporary theories and models of IC about the main focus of two paradigms: the ‘cognitive/affective/behavioral’ paradigm and the developmental paradigm, which seems to be mostly used, since developing intercultural competence is a lifelong process acquired through intercultural experiences and encounters (Hammer, 2015).

The IDI was created as a cross-culturally valid assessment of the DMIS and has been tested in diverse cultures and contexts (Dejaeghere & Cao, 2009; Nam, 2011; Paige et al., 2004; Wang & Kulich, 2015; Yuen & Grossman, 2009). Its use provided instructors and students with a “frame of reference to follow-up discussion, [it also] lends a sense of legitimacy to the instrument itself, and serves as the reference point for psychometric analysis” (Paige, 2004, p. 91).

Furthermore, IDI research findings “have infused international education with targeted study abroad program designs that are significantly increasing the intercultural competence of students” (Hammer, 2015, p. 13).

Methodology

Research design

The researchers employed a pre-post test comparison group design with the instruments administered before and after the study abroad program. The design of this study was based on the time frame of the core courses and compulsory semester study abroad established in the degree program (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Timeline research project and intercultural learning interventions

Note: Own elaboration.

The compulsory courses Intercultural Communication and Intercultural Mediation were taught by the two main researchers of this study during the third year of the degree program. These courses were planned and programmed together with the specific aim of developing the students’ IC through the acquisition of a set of knowledge, attitudes and skills, and to prepare them not only for their professional future, but also for their compulsory semester study abroad.

As Figure 1 illustrates, the pretest took place in September 2010 and the in-depth personal interviews were done immediately after the pretest. In the fall semester of the participants’ fourth and final year, they completed a compulsory semester abroad as part of the ERASMUS exchange program. Upon their return, participants took a post-IDI test and participated in post-in-depth personal interviews. As previously mentioned, the study was intentionally conducted with the first cohort of students since the aim was applying its results in the subsequent years.

Method

This is a case study, understood as an empirical inquiry that deeply investigates a contemporary event in a real-life context (Yin, 2009) and whose aim is to study a particular case intensively in order to, at least partially, shed light on a greater number of cases (Gerring, 2007). Researchers wanted to expand on the findings of IDI version 3 with qualitative personal interviews.

Regarding the personal interviews, the focus was on the process of understanding the meaning of the participants’ intercultural experiences and misunderstandings. The interviews attempted to promote reflection on students’ intercultural encounters (Nardon, 2017). This gave the researchers the opportunity to look into the detailed personal aspects of the students’ intercultural development and encouraged the participants to reflect on and connect their learning with their own personal experiences (Merriam, 2009).

Tools

The Intercultural Development Inventory

The use of instruments in intercultural training has existed since the 1970s (Fantini, 2009). However, as inferred from the state of the art, there is a lack of research published about the use of the IDI in the Spanish context. To select the use of the IDI in this research we took into account: requirements for using the instrument, scoring options, administration issues, cost, accompanying materials, training programs, theoretical and empirical base, validity and reliability, usefulness and finally existing evidence that the instrument is currently in use in intercultural training (Paige, 2004).

The IDI generates an individual or group profile with five different scores for the Denial/Defense, Reversal, Minimization, Acceptance/Adaptation, and Encapsulated Marginality Scales (Paige, 2004). One of the purposes of the use of the IDI is to evaluate and assess an educational program, and the effectiveness of different training and education interventions, as well as to improve the intercultural competence of participants. Respondents can describe their intercultural experiences “in terms of … their cross-cultural goals, … the challenges they face navigating cultural differences … [and] critical (intercultural) incidents they encounter around cultural differences” (Hammer, 2012, p. 117). Finally, since participants in this research had studied Bennett’s Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS) (1993) in class, the use of the IDI helped them reflect upon their own learning and results, what was evident during the personal interviews.

In-depth personal interviews

In addition to the quantitative method, we employed in-depth personal interviews that were taped, transcribed and analyzed. The software NVivo 10 was used for coding and analyzing the interviews.

Interviews were one of the most important sources of evidence and were key in understanding the developmental growth of the participants, nurturing the quantitative part of the study. They took place after taking the IDI tests in order that participants were able to comprehend their individual results and to understand and discuss some of Bennett’s (1993) DMIS concepts. In particular, they helped to assess cross-cultural goals, challenges and critical intercultural incidents, providing very valuable information from respondents’ cultural experiences (Hammer, 2012).

The administrator gave each participant feedback about their individual IDI results and the students learned about their primary orientation on the continuum. Students were encouraged to use that knowledge to continue their IC development.

Regarding the interviews that took place after the pre-IDI test, the questions were: 1) Why do you think that you have these results in the IDI test? 2) Could you recall any past intercultural experiences that may have led you to this stage? 3) How do you think you could further develop your intercultural competence?

Concerning the interviews that took place after the post-IDI test, the questions were: 1) How would you use the knowledge, skills and attitudes developed during the courses on Intercultural Communication and Intercultural Mediation in your near future? 2) How could courses like these be useful for university students in other degree programs? 3) How have these courses made you reflect about your experiences and about other’s experiences? 4) How could your experience abroad have an impact on the development of your intercultural competence?

Participants

The sample was (N = 14), the entire first cohort of students in a Translation and Intercultural Communication degree; 13 participants were Spanish and 1 Belgian, all female and with ages between 20-23 years old.

Results and Analysis

IDI results and analysis

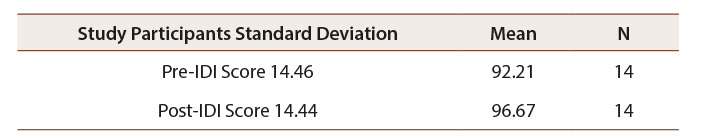

Regarding intercultural development, the first finding was that participant students made some progress in their intercultural learning between the pre-IDI test and the post-IDI test. According to the pre-IDI and post-IDI of the group profile, there was an increase in the students’ Developmental Score (Table 1).

Table 1: IDI Group Profile Scores

Note: Own elaboration.

The group profile scores show that the participants were within Minimization, which reflects a tendency to highlight commonalities across cultures. Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that there is an important differentiation between the IDI stages and the DMIS levels. According to Hammer (2012), while Minimization in Bennett’s DMIS is still an ethnocentric stage in which worldviews are still separated into us and them, in the IDI continuum, the stage of Minimization is considered to be an ethno-relative stage or part of the intercultural spectrum. In this mindset participants are able to understand and see cultural differences and similarities between cultures, tending to use generalizations in order to recognize cultural differences. However, it is considered a transitional stage from an ethnocentric stage into an ethno-relative one in which people have more cultural categories and start realizing that cultural differences are important in how people behave.

As can be inferred from Table 1, the mean of the pre-IDI test was 92.21 and the mean of the post-IDI score was 96.67. As a group, the sample’s developmental orientation (DO) or intercultural competence improved over a period of four semesters. The mean of the group’s Developmental Score was 4.45 and the standard deviation 9.63 (See Figure 2).

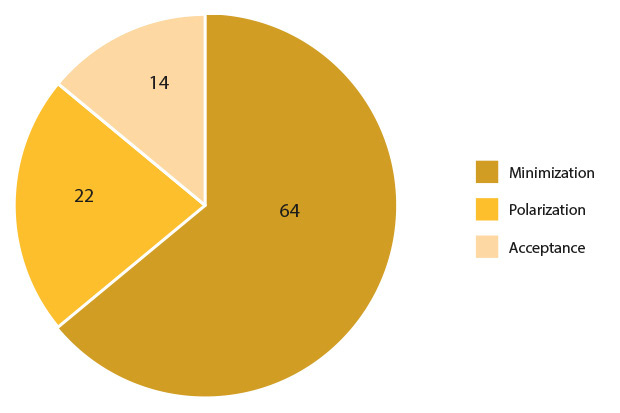

Figure 2: Pre-Test IDI group profile developmental orientations

Note: Own elaboration.

As Figure 2 illustrates, 57% of the students participating in the study when taking the pre-test were within the stage of Minimization, 14% were within Acceptance and 29% were within Polarization; 71% of the students were within the intercultural mindsets and 29% were within a stage of mono-cultural mindsets. This could be considered a high pre-test DO. We need to take into account our assumptions mentioned above: the students participating in the study already had interests in other languages and cultures and some previous international experience, since they decided to study Translation and Intercultural Communication (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Post Test IDI group profile developmental orientations

Note: Own elaboration.

Figure 3 shows that when taking the post-IDI test 64% of the students were within the stage of Minimization, 21% were within Acceptance and 14% were within Polarization.

There was a meaningful increase in the two stages of the intercultural mindset, and a significant decrease in the percentage of students in Polarization, within the mono-cultural mindset.

Overall, the study results show that 64% of the participants improved their intercultural competence scores over the period of almost two years. In addition, 43% of the participants showed an improvement of over seven points in their Intercultural Competence Development Orientation. It can be inferred that 29% of the participants improved their Developmental Scores and shifted from one stage on the continuum to the next. Sixty-four percent of the participants remained within the same stage of the continuum between pre and post-tests. It is important to highlight that this 64% were all within ethno-relative stages. Most of the students who significantly increased their Developmental Scores had never previously lived or remained more than six months in another country.

On the other hand, the study results confirm that the Intercultural Competence Development Orientation Scores of 28% of the participants decreased very slightly, between 0.86 and 3 points. Only 14% of the participants showed a significant decrease in their Intercultural Competence Developmental Orientation Scores (in total, only one of the 14 participants). Most participants whose Developmental Scores decreased, remained in the same stage as when they took the pre-test. According to Vande Berg (2017), previous IDI research studies and research records have shown that learners do not usually reach the highest stages of IC development in such a short period of time, since IC acquisition is a developmental process. In fact, learners improve their IC development when they have experienced a learning intervention.

An important finding of the study is not only the group results but also those individual cases that are worthy of note due to substantial score increase and IC development. Regarding the highest increase in the DO scores (see Table 2), one participant shifted from Minimization to Acceptance, with an increase of 28.38 points. In this case, the student had not lived abroad for more than three months before her compulsory study abroad experience.

Table 2: Student’s highest increased DO results

Note: Own elaboration.

Personal interviews results & analysis

With regard to the in-depth personal interviews, the common themes that emerged from their analysis were three: the importance of training in developing intercultural competence; reflection about past intercultural experiences based on previously acquired knowledge and skills; the impact of training during study abroad experiences.

The importance of training in developing IC

Concerning the interviews carried out after the pre-IDI test, they served as a means to reflect upon the students’ Developmental Scores and, also about past intercultural experiences that might have shaped their views and conceptions about other cultures (Vande Berg, 2017). As most of the students declared during the personal interviews, the IDI had helped them to reflect upon why they wanted to study Translation and Intercultural Communication as well as in which areas they had to work before and during their compulsory study abroad experience. Students were able to open up to the interviewer, maintaining a high intellectual level during the conversation. They demonstrated an in-depth understanding of the models used in classes as well as their relation to personal experiences.

Impact of training during study abroad experiences

During the post-IDI interviews, the students showed maturity and reflection about their previous training and their study abroad experiences. They affirmed that they had reflected upon what they learned in the Intercultural Communication and Intercultural Mediation courses and, that they were now more aware about what was happening to them during their study abroad experience. They were able to connect the theory they had learned with the experience they had. They all had positive learning experiences abroad and, most of them confirmed their intentions of continuing their studies or working abroad once they graduated (in a recent study, unpublished, in which some of these students were interviewed, it showed how these courses have had an effect on their professional lives). As Lola pointed out, she was ready to become a cultural bridge: I am ready to help others, to help the community to understand different cultures and what happens when you go abroad. At the same time, Blanca stated how these courses and taking the IDI helped her to heal from a stressful intercultural experience (related to losing a loved one in the March 2004 train bombings in Madrid) into a more understanding vision of what really had happened: You know, I really have worked hard on my hate, stereotypes and prejudices… and I think I can see more clearly about what happened then… it has been a healing process, and I am very thankful for that. This statement shows great maturity and personal work, trying to connect a stressful experience previous to college education with what she was learning during her university degree. This student is moving from essentialism into cosmopolitanism or from an ethnocentric stage into an ethno-relative one, since she is discarding stereotypes and prejudices about one community (the Muslim community) and beginning to see it as a heterogeneous group without static characteristics.

Reflection about past intercultural experiences based on previously acquired knowledge and skills

When the students were asked in the post-IDI interviews if the Intercultural Communication and Intercultural Mediation courses had made them reflect about their intercultural experiences and about the experiences of others, 93% of them totally agreed and 7% tended to agree. Patricia pointed out: I think that courses such as Intercultural Communication induce you to reflect. I have learned more than just theory, I have learned about my own experiences and about my skills, abilities and intercultural competences. I learned how to analyze others trying to understand their realities. The significant learning that helps the development of IC is clearly reflected here. It shows how the methodologies used in class promoted experiential learning and reflection that led to significant learning.

The students were also asked if they thought that specific courses on Intercultural Communication and Intercultural Mediation would be useful in their near future, to which 64% of them responded affirmatively. Carmen admitted that after learning so much from these courses I would like to teach others, you know…it is like Peggy Mackintosh’s backpack, after all, life is a transfer of knowledge. Working abroad means an absolutely challenging and appealing chance I am not going to miss. Luckily by the year 2020 I will have my bag of intercultural knowledge packed. In more recent unpublished research projects, students from this cohort were asked about their perceptions of their development of intercultural competence and they affirmed that their degree and courses helped them greatly in acquiring and developing this competence.

Participants were also asked if they would recommend students from other degree programs to take courses about Intercultural Communication and Intercultural Mediation, to which 79% of them answered they totally agreed and 21% of them somewhat agreed. A 21st century higher education institution should offer an internationalized curriculum as well as internationalized activities, bringing opportunities for ALL students to access a more cosmopolitan and internationalized education. This is key to educating global citizens.

These findings provide support for the main study’s assumptions: intercultural learning interventions help students to increase their intercultural competence. The integration in a university’s main curriculum of courses such as Intercultural Communication and Intercultural Mediation plus a post study-abroad experience can provide important opportunities for increasing IC. It is true that we would have liked to see more improvement and that made us reflect upon what kind of interventions should be revised and which should be added in order to see a greater development of these competences. It helped us to acquire a broader vision of what type of curriculum should be offered in any university. After analyzing the results of this study we reviewed the contents of the core courses with the aim of obtaining a more significant improvement in the students’ IC.

Discussion

The students increased their intercultural development by 4.45 points on the IDI, after taking Intercultural Communication and Intercultural Mediation courses as well as having a study abroad experience. The results of the qualitative post-study abroad interviews showed that the students had increased their understanding of cultural differences and they had reflected about their intercultural misunderstandings, which is key for developing IC (Nardon, 2017). The personal interviews in this study show important results when measuring significant learning. The degree of reflection and the depth of the analysis that the students showed were relevant.

Intercultural learning interventions help learners to become aware “that their assumptions and the patterned ways they experience these are holistic, that they experience emotionally, perceptively, cognitively, and behaviorally” (Vande Berg, 2017, p. 231). They promote experiential and developmental opportunities for students to reflect on how they understand and construct their culture and reality.

All participants provided good examples of how the knowledge they had acquired about cultural variables and different communication styles before studying abroad were very helpful during their daily interactions in the host countries, as well as when they returned to Spain. They showed how hard they worked to demolish stereotypes and work on their own prejudices. This is directly linked to the courses content but also to the methodologies applied during those courses.

Experiences abroad alone are not enough to develop IC and their results are highly variable. Allport (1954) as well as later on Pettigrew (1998, 2008) and Pettigrew and Tropp (2000), proved that simply diversity in the classroom will not make students develop intercultural competence. In addition, several studies, such as The Maximizing Study Abroad Guide (Paige et al., 2002) and the Georgetown consortium project show that students participating in these experiences might return home more ethnocentric than before and less willing to interact with people who are culturally different (Cressy, 2021; Prieto-Flores et al., 2016). It all depends on how positive their relationships were while studying abroad. As a result, we consider that in the future it would be useful to have a three-credit (ECTS) online course during the compulsory semester abroad experience, or upon returning from the study abroad experience, since as Paige and Vande Berg (2012, p. 38) explain, “students abroad learn most effectively–and appropriately–when educators take steps not only to immerse them, but to actively facilitate their learning, helping them reflect on how they are making meaning from the experiences that their ‘immersion’ is providing”. If we want to give our students a quality education, an education for the 21st century, we can affirm that it is insufficient to get students to “just” study abroad and it is crucial to guide the learning process of the students while abroad (Paige & Vande Berg, 2012).

As for future research, we propose that further studies are needed in this field within the Spanish and the European context and in different degree programs, and we suggest several improvements in the sequencing and design of the research study to make it more robust. We believe that the implementation of the EHEA brought European universities a great opportunity to revise and rethink their degree programs. We should take this great opportunity and rethink programs in order to promote key competences in our future university graduates and educate them to be global citizens. We cannot continue to teach the same content the same way just changing the names of courses offered. An internationalized curriculum that helps university students access an internationalized education and helps them become interculturally competent global citizens is a must in 21st century universities. This study is an example of the impact that this type of courses has on university students.

As for the research project, we would add a control group with whom we could compare the pre-post IDI results, which could give a better indication of the development of intercultural competence. We would also implement a compulsory online course during the study abroad experience and some re-entry workshops. It would also be important to have three tests, a pre-test, another IDI test before compulsory study abroad and a post-test immediately after they return.

Conclusions

Our society is connected and global and our students will work and interact in this context. It is key that we train them to be able to manage the work and interaction between people who are very different from them and to appreciate and embrace diversity as a treasure and not as a threat. Universities have an important mission that is to educate global citizens. Therefore, it is important that intercultural learning interventions should be included as compulsory courses within the curriculum of all university degree programs, and that, as this study shows, two courses and a short period abroad alone are good but not enough.

There is indeed a lot of talk about the importance of the internationalization of European universities, and how the main element is the internationalization of the curriculum (IoC) (Green & Whitsed, 2015). Egron-Polak & Hudson (2010, as cited in Beelen, 2013, p. 137) affirms that, according to the 2010 Global Survey, “Europe as a whole scores low on ‘strengthening the international/intercultural content of the curriculum’”. The case presented here is an example of a learning outcome of IoC which according to Green and Mertova (2009, cited in Green & Whitsed, 2015, p. 7) are: “Global perspectives …, intercultural competence … [and] responsible global citizenship”. Leask (2005, cited in Green & Whitsehd, 2015, p. 7) affirms that “internationalisation of a curriculum should not be seen as an ‘end’ in itself, [but it should focus on what students learn from an internationalized curriculum]”.

In short, this is an example of an intercultural learning intervention in a degree program within a private Spanish university that we think can be useful for the programming and design of other degree programs in the EHEA within a similar context. It is true that Southern European countries lack research in this area, and we would like to encourage our colleagues in countries such as Portugal, Spain, Italy and Greece (countries sending and receiving more international students than other European countries every year) to develop research studies similar to this one and to publish their results.

Intercultural learning interventions do matter and bring results. They have an impact on students’ intercultural competence development and intercultural learning which do not happen and develop naturally. European universities should take the EHEA opportunity to transform and to internationalize their courses. According to Savicki and Selby (2008, p. 348), it is key to understand that, when we talk and research into IC, its development is a process, “they are journeys not destinations”. There are indeed different levels of IC depending on each student’s readiness, the quality of the intercultural experience and/or study abroad experience, as well as the access to training and support before, during, and after the cultural immersion experience.

Assessing IC is a value–added enterprise to any student education degree as well as to any university program. However, as we have shown in this case study, it is an individual journey, not all students will end at the same place, because they do not all start at the same point. But what really matters is movement and transformation of IC, which does not happen in just one moment of life. The learning interventions plus the study abroad experience may be the first stage for more shifts later on in students’ lives.

Declaración de Material complementario

Este artículo tiene disponible, como material complementario:

-La versión preprint del artículo en https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4906877

Declaración de contribuciones

Las personas autoras declaran que han contribuido en los siguientes roles: M. L. S. H. contribuyó con la escritura de la versión postulada del artículo; la gestión del proceso investigativo; la obtención de fondos, recursos y apoyo tecnológico y el desarrollo de la investigación. A. N. L. contribuyó con la escritura de la versión postulada del artículo; la gestión del proceso investigativo; la obtención de fondos, recursos y apoyo tecnológico y el desarrollo de la investigación.

References

Agencia Nacional de Evaluación de la Calidad y Acreditación. (2004). Libro blanco, Título de grado en traducción e interpretación. Resource document. Autor.

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley.

Beelen, J. (2013). The current debate and current trends in iah. In J. Beelen, A. Boddington, B. Bruns, M. Glogar, & C. Machado (Eds.), Guide of good practices. Tempus Corinthiam. Project No. 159186-2009-1-BE-SMGR (pp. 133-145). Tempus. https://www.academia.edu/10267866/Beelen_J_2013_The_current_debate_and_current_trends_in_IaH

Bennett, M. J. (1993). Towards ethnorelativism: A developmental model of intercultural sensitivity. In R. M. Paige (Ed.), Education for the intercultural experience (pp. 21-71). Intercultural Press.

Bennett, J. M. (2008). On becoming a global soul. A path to engagement during study abroad. In V. Savicki (Ed.), Developing intercultural competence and transformation. Theory research and application in international education (pp. 13-31). Stylus Publishing.

Byram, M., Nichols, A., & Stevens D. (Eds.) (2001). Developing intercultural competence in practice. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781853595356

Cressy, K. C. (2021). Students’ intercultural development during faculty-led short-term study abroad: A mixed methods exploratory case study of intercultural intervention[Doctoral dissertation, University of Minnesota]. https://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/223180

Deardorff, D. (2006). Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. Journal of Studies in International Education, 10(3), 241-266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315306287002

Deardorff, D. K. (2014). Some thoughts on assessing intercultural competence. University of Illinois and Indiana University, National Institutefor Learning Outcomes Assessment.

Dejaeghere, J. G., & Cao, Y. (2009). Developing U.S. teachers’ intercultural competence: Does professional development matter? International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33(5), 437-447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.06.004

Engle, L., & Engle, J. (2012). Beyond immersion: The American University Center of Provence experiment in holistic intervention. In M. Vande Berg, R. M. Paige, &

K. H. Lou (Eds.), Student learning abroad: What our students are learning, what they’re not, and what we can do about it (pp. 284-307). Stylus Publishing.

Fantini, A. E. (2009). Assessing intercultural competence: Issues and tools. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 456-476). Sage Publications.

Gerring, J. (2007). Case study research. Principles and practices. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511803123

Green, W. & Whitshed, C. (2015). Introducing critical perspectives on internationalizing the curriculum. In W. Green and C. Whitshed (Eds.), Critical perspectives on internationalizing the curriculum in disciplines: Reflective narrative accounts from business, education and health (pp. 3-22). Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-085-7_1

Hammer, M. R. (2012). The intercultural development inventory: A new frontier in assessment and development of intercultural competence. In M. Vande Berg, R. M. Paige and K. H. Lou (Eds.), Student learning abroad. What our students are learning, what they’re not, and what we can do about it (pp. 115- 136). Stylus Publishing.

Hammer, M. R. (2015). The developmental paradigm for intercultural competence research. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 48, 12-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.03.004

Hernández-Moreno, B. (2021). Intercultural competence and its Assessment: A critical contextualisation. In A. Witte, T. Harden (Eds.), Rethinking intercultural competence: Theoretical challenges and practical issues (pp.85-105). Peter Lang.

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Jossey Bass.

Mirzoyeva, L., & Syurmen, O. (2016). Developing intercultural competence of trainee translators. Global Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 6(3), 168-175. https://doi.org/10.18844/gjflt.v6i3.1663

Nam, K.-A. (2011). Intercultural development in the short–term study abroad context: A comparative case study analysis of global seminars in Asia (Thailand and Laos) and in Europe (Netherlands). The University of Minnesota. https://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/104702

Nardon, L. (2017). Working in a multicultural world: A guide to developing intercultural competence. University of Toronto Press. https://doi.org/10.3138/9781442625006

Olk, H. M. (2009). Translation, cultural knowledge and intercultural competence. Journal of Intercultural Communication, (20), 1-12. https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/50685756/translation-cultural-knowledge-and-intercultural-competence

Paige, R. M. (2004). Instrumentation in intercultural training (Chapter 4). In D. Landis, J. M. Bennett, & M. J. Bennett (Eds.), Handbook of intercultural training (pp. 85-128). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452231129.n4

Paige, R. M., & Vande Berg, M. (2012). Why students are and are not learning abroad. In M. Vande Berg, R. M. Paige, & K. H. Lou (Eds.), Student learning abroad: What our students are learning, what they’re not, and what we can do about it (pp. 29- 58). Stylus Publishing.

Paige, R. M., Cohen, A. D., & Shively, R. L. (2004). Assessing the impact of a strategies-based curriculum on language and culture learning abroad. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 10(1), 253-276. https://doi.org/10.36366/frontiers.v10i1.144

Paige, R. M., Cohen, A. D., Kappler, B., Chi, J. C., & Lassegard, J. (2002). Maximizing study abroad: A student’s guide to strategies for language and culture learning and use. University of Minessota CARLA.

Pettigrew T. F. (1998). Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review Psychology, 49, 65-85.

Pettigrew, T. F. (2008). Future directions for intergroup contact theory and research. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32(3), 187-199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2007.12.002

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2000). Does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Recent meta-analytic findings. In S. Oskamp (Ed.), Reducing prejudice and discrimination (pp. 93-114). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Prieto-Flores, O., Feu, J., & Casademont, X. (2016). Assessing intercultural competence as a result of internationalization at home efforts: A case study from the Nightingale Mentoring Program. Journal of Studies in International Education 20(5), 437-453. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315316662977

Rodríguez-Izquierdo, R. M. (2022). International experiences and the development of intercultural sensitivity among university students. Educación XX1, 25(1), 93-117. https://doi.org/10.5944/educXX1.30143

Savicky, V., & Selby, R. (2008). Synthesis and conclusions. In V. Savicky (Ed.), Developing intercultural competence and transformation. Theory, research, and application in international education (pp. 342-352). Stylus.

Tomozeiu, D., Koskinen, K., & D’Arcangelo, A. (2016). Teaching intercultural competence in translator training. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 10(3), 251-267. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2016.1236557

Universidad San Jorge. (n.d.). Traducción y comunicación intercultural. Autor. https://www.usj.es/estudios/grados/traduccion-comunicacion-intercultural/plan-estudios

Vande Berg, M. (2017). Developmentally appropriate pedagogy. In J. M. Bennett (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of intercultural competence (Vol. 1, pp. 229-233). SAGE Publications.

Vande Berg, M., Connor-Linton, J., & Paige, R. M. (2009). The Georgetown Consortium Project: Interventions for student learning abroad. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 18, 1-75.

Wang, Y. & Kulich, S. J. (2015). Does context count? Developing and assessing intercultural competence through an interview-and model-based domestic course design in China. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 48, 38-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.03.013

Witte, A. & Harden, T. (2021). Intercultural competence-introduction. In A. Witte & T. Harden (Eds.), Rethinking Intercultural Competence: Theoretical Challenges and Practical Issues (pp.1-17). Peter Lang.

Yarosh, M. (2012). Translator intercultural competence: The concept and means to measure the competence development (Doctoral dissertation, University of Deusto). https://www.proquest.com/openview/0557465c9eaa5ad959c098b81e495e1f/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research. Design and methods (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Yuen, C. Y. M., & Grossman, D. L. (2009). The intercultural sensitivity of student teachers in three cities. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 39(3), 349-365. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920802281571

Artículo de la Revista Electrónica Educare de la Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica by Universidad Nacional is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Costa Rica License.

Based on a work at https://www.revistas.una.ac.cr/index.php/EDUCARE

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at educare@una.ac.cr