Revista Electrónica Educare (Educare Electronic Journal) EISSN: 1409-4258 Vol. 26(1) ENERO-ABRIL, 2022: 1-20

doi: https://doi.org/10.15359/ree.26-1.19

http://www.una.ac.cr/educare

educare@una.ac.cr

[Cierre de edición el 01 de Enero del 2022]

Negative Stereotypes Towards Older People. A Study with Teachers in Initial Training

Estereotipos negativos hacia las personas mayores. Un estudio con profesorado en formación inicial

Estereótipos negativos para as pessoas idosas. Um estudo com professores em formação inicial

Pilar Moreno-Crespo

Universidad de Sevilla

Sevilla, España

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6226-0268

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6226-0268

Olga Moreno-Fernández

Universidad de Sevilla

Sevilla, España

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4349-8657

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4349-8657

Encarnación Pedrero-García

Universidad Pablo de Olavide

Sevilla, España

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0650-7729

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0650-7729

Recibido • Received • Recebido: 07 / 04 / 2020

Corregido • Revised • Revisado: 08 / 10 / 2021

Aceptado • Accepted • Aprovado: 03 / 11 / 2021

Abstract:

Objective. To describe whether there are stereotypes towards older adults by the group of teachers in initial training. Method. The approach was quantitative and not probabilistic through a statistical study with university students preparing to become primary school teachers in the Spanish education system. This training profile includes adult and senior education as an additional professional opportunity. The sample (n=110) has been selected among students of the Primary Education Degree. We have applied the Negative Stereotype Questionnaire for the Elderly (CENVE) and the Educational Stereotype Questionnaire for the Elderly (CEEAM). Results. We suggest that the respondents present some degree of stereotypes towards older adults; the stereotype is greater when we question the deterioration of memory and cognitive impairment in general. However, the data are positive, except that in the case of the health factor we found two items in which respondents reported a higher level of stereotyping. Conclusions. Based on these results, we conclude that it is necessary to work on stereotypical perceptions, especially with students pursuing careers related to education, since their professional performance can lead them to develop their teaching careers in adult and senior education. The education professions must be involved in improving quality of life, active aging, and lifelong learning through professional practice and the elimination of personal and societal stereotypes.

Keywords: Education; stereotypes; older adults; teachers in initial training.

Resumen:

Objetivo. Describir si existen estereotipos hacia las personas adultas mayores por parte del profesorado en formación inicial. Metodología. El enfoque fue cuantitativo y no probabilístico a través de un estudio estadístico con estudiantado universitario que se prepara para ser docente de primaria en el sistema educativo español. Este perfil de formación incluye la educación de personas adultas y de la tercera edad como una salida profesional adicional. La muestra (n=110) ha sido seleccionada entre el estudiantado del Grado de Educación Primaria. Hemos aplicado el Cuestionario de Estereotipo Negativo para la Tercera Edad (CENVE) y el Cuestionario de Estereotipo Educativo para la Tercera Edad (CEEAM). Resultados. Sugerimos que las personas encuestadas presentan algún grado de estereotipo hacia las personas adultas mayores; el estereotipo es mayor cuando cuestionamos el deterioro de la memoria, así como cuando cuestionamos el deterioro cognitivo en general. Sin embargo, los datos son positivos, aunque en el caso del factor salud encontramos dos ítems en los que las personas encuestadas denotan un mayor nivel de estereotipo. Conclusiones. A partir de estos resultados, concluimos que es necesario trabajar sobre las percepciones estereotipadas, especialmente en aquel estudiantado que está siguiendo carreras relacionadas con la educación, ya que su desempeño profesional puede llevarlo a desarrollar su carrera docente en la educación de personas adultas y en la educación superior. Las profesiones educativas deben estar implicadas en mejorar la calidad de vida, el envejecimiento activo y la formación permanente desde el ejercicio profesional y la eliminación de estereotipos personales y de la sociedad.

Palabras claves: Educación; estereotipos; personas adultas mayores; profesorado en formación inicial.

Resumo:

Objetivo. Descrever se existem estereótipos para as pessoas idosas por parte do grupo de professores em formação inicial. Metodologia. A abordagem foi quantitativa e não probabilística por meio de um estudo estatístico com estudantes universitários que se preparam para se tornarem professores do ensino primário no sistema educativo espanhol. Este perfil de formação inclui a educação de pessoas adultas e também idosas como um meio profissional adicional. A amostra (n=110) foi selecionada entre estudantes do Grau do Ensino Primário. Foi aplicado o Questionário de Estereótipo Negativo para Idosos (CENVE) e o Questionário de Estereótipo Educativo para Idosos (CEEAM). Resultados. Sugerimos que as pessoas entrevistadas apresentam algum grau de estereótipo sobre os idosos; o estereótipo é maior quando questionamos a perda de memória, bem como a perda cognitiva em geral. No entanto, os dados são positivos, embora no caso do fator saúde foram encontrados dois itens em que as pessoas entrevistadas denotam um nível mais elevado de estereótipo. Conclusão. A partir destes resultados, concluímos que é necessário trabalhar sobre percepções estereotipadas, especialmente com estudantes que seguem carreiras relacionadas com a educação, uma vez que o seu desempenho profissional pode levá-los a desenvolver a sua carreira docente na educação de pessoas adultas e no ensino superior. As profissões educacionais devem estar envolvidas na melhoria da qualidade de vida, no envelhecimento ativo e na formação permanente através da prática profissional e da eliminação de estereótipos pessoais e sociais.

Palavras-chave: Educação; estereótipos; pessoas idosas; professores em formação inicial.

Introduction

Demographic data in Spain indicate that life expectancy has increased by more than 40 years in the last century, which has led to a demand for education that in other historical moments had not been given because life expectancy was much lower, making adult education practically unnecessary due to lack of demand by the population. Eighty-six out of every hundred Spaniards born today will celebrate their 65th birthday; at the beginning of the twentieth century only twenty-six out of every hundred Spaniards were able to reach that age (Instituto de Migraciones y Servicios Sociales [IMSERSO], 2002). These demographic changes have led to political, social, cultural and economic changes, which have led to the need for people to be trained throughout life, a comprehensive education that includes learning knowledge, attitudes for the exercise of citizenship, the growth of the person and communities themselves (Lucio-Villegas Ramos, 2011).

Faced with this reality, in the field of adult education, there is a constant increase in the number of students who are getting older and older, so we can talk about older students. For this reason, attention should also be paid to professionals who will act as adult trainers/educators (pedagogues, social educators and primary school teachers, mainly). As Matas Terrón et al. (2017), the students of Education must be prepared to attend to these formative needs of the elderly. In this way, the education system in all its stages must contemplate promoting the change of attitudes towards older adults in curricular designs, allowing them to be an integral and active part of society (Matas et al., 2017; Melero Marcos, 2007). There is a large body of research on initial teacher education (Cascone et al., 2020; Gómez-Camacho et al., 2021; Gómez-Carrasco et al., 2020; However, there is still little research on how to deal with the stereotypes that future teachers have when faced with the possibility of having older adults as pupils This is important for the inclusive educational care of this group.

We wonder, therefore, about the stereotypes that teachers in initial training have about the group of older adults. The ageing process is surrounded by a series of beliefs and stereotypes related to the lack of physical health, loss of cognitive processes, loss of vital functions, dependency, inability to face new challenges, acidity of character, etc., which have little or nothing to do with reality on many occasions. All these beliefs and stereotypes that revolve around ageing, and therefore around the figure of the elderly, generate a social imaginary that negatively influences how this collective is perceived.

Claiming that the fact of reaching a certain age automatically adopts a series of cognitive, physical, biological, social, etc. characteristics is far from logic. That is, to consider any person over sixty-five years old has an arbitrary and unreasonable explanation (Pérez Serrano, 2004). Each person, in their individuality, is different from the rest, and their ageing process is unique and personal. Therefore, we must understand that there are different ways of understanding and carrying the ageing process (Da Silva Oliveira et al., 2017; Serrate González et al., 2017;

The phenomenon of population ageing is currently a challenge that requires effective public policy responses. It poses the dilemma of creating favourable conditions so that people can fully live this stage of life in the best possible conditions. According to Weaver (1999), the social image of the ageing process and, therefore, of older adults, must change as a strategy to confront generalizations about the collective, as well as myths and stereotypes about this stage of life.

If we consider Montoro Rodríguez’s (1998) definition of stereotypes we would be referring to those ideas that most of a group of individuals have about a series of personal characteristics, this tends to be the result of simplifications, which implies biased opinions. The force that exists in stereotypes, as Amador et al. (2001) point out is that they can be transformed into functional schemes that direct acts rather than reality itself.

Stereotypes do not correspond to reality, and therefore there is a tendency to confuse the extent to which certain social conventions are false or true. These stereotypes can lead to attitudes that may encourage discriminatory behavior towards members of a particular group. In the case of ageism, these are age-related prejudices. It is usually a negative prejudice, we can associate it with the concept of old, but there are times when it has a positive component. In these cases, it is often associated with aspects such as wisdom or goodness, but they are still stereotypes (Fernández-Ballesteros et al., 2016; Fernández-Ballesteros et al., 2017; Pinazo-Hernandis et al., 2016; Sanhueza, 2014).

The age group project is beginning to be increasingly studied due, among other factors, to the increase in its sociodemographic representativeness and longevity. Therefore, we find that there is an increase in publications on stereotypes towards ageing and older adults towards ageing in other age groups (Aristizábal-Vallejo, 2004; Lasagni Colombo et al., 2013). Through these studies it has been proven that the most common beliefs towards this stage are those that associate it with illness, with deterioration of physical and cognitive abilities and lack of vital interests.

We also highlight the increase in publications on stereotypes towards ageing from the perception of university students (Campos-Badilla & Salgado-García, 2013; Duran-Badillo et al., 2016; Portela, 2016), although all of them focus on careers related to Health Sciences, such as medicine, nursing, or psychology. Few research studies study the perception of university students of degrees related to the field of education (Pedrero-García et al., 2018).

We are especially interested in this population, teachers in initial training, because they will be professionals who will give formal educational support to the group of older adults. It is known that stereotypes are part of culture, however, when they are negative stereotypes on the part of students in education-related careers such as the Magisterium, it is worrying due to the social relevance of their professional performance. Therefore, the challenge facing today’s society is to promote an environment that favors the development of society in general and older people in particular, as well as to try to overcome the stereotypes prevailing today, especially in some professionals, teachers, who will play a fundamental role in the development of the group of older adults (Cruz Díaz et al., 2013; Moreno-Crespo, 2019; Moreno-Crespo & Pérez-Pérez, 2014).

The studies mentioned above have provided a useful insight into the stereotypes of the elderly although in the field of health professionals. There are still few studies that focus on the stereotypes of this group in the field of education. Without a doubt, older adults are an objective sample with which future teachers will have to work in their classrooms. Therefore, we consider that this work has a greater value if we bear in mind the lack of research by Spanish academics on the perception that future teachers have about the group of older adults.

The purpose of this research is to examine whether there are stereotypes of older people by the group of teachers in initial training at four different levels or areas: those related to educational skills, health, those related to motivational and social issues and, finally, character. Addressing these four factors gives us a complex view of the field of study.

Research Methodology

The research was quantitative and not probabilistic (Canales Cerón, 2006; Hernández Sampieri et al., 2006) on the stereotypes of teachers in initial training for the older age group. Although this is a topic studied in the field of health professionals, there is no background to focus the research on education professionals.

The sample, randomly selected, is made up of 110 teachers in initial training who were in the third year of the Grade of Primary Education at the University of Seville (Spain). The sample has carried out their internships in educational centres and, therefore, they have had a first approach to what will be their professional performance. It is in the third year that the basic training shared by future teachers comes to an end, since in the fourth year there is a specialisation in training.

The instrument used in this investigation is based on two questionnaires on stereotypes towards ageing. On the one hand, there is the Evaluation Questionnaire of Negative Stereotypes on Ageing (CENVE) (Blanca Mena et al., 2005), which is an adaptation of the Facts on Ageing Quiz (FAQMH) of Montorio and Izal (1991) and Palmore (1977), which contains 15 closed questions and three factors: health, motivational-social and character-personality. On the other hand, the Questionnaire on Educational Stereotypes of the Elderly is used, which despite its relatively recent creation, has the endorsement of the literature review, the objectives of the study and the practice of researchers, university professors.

In the case of CEEAM, it was validated from two different processes: the first version of the questionnaire was discussed with 2 experts in the field, experienced in research orientation and broad educational practice in the field of initial training. Reforms were suggested regarding the use of language appropriate to the educational reality. After the reformulation, a pre-test was carried out with 6 students in initial training, not participants of the sample, who made judgments about the clarity, relevance, appropriateness of the questions, the time needed in their realization and the visual aspect (Hill & Hill, 2002). The suggestions made by these students regarding the format of the questionnaire presentation are taken into account. The final questionnaire consisted of 13 closed questions and one factor: education. Both the CENVE and the CEEAM questionnaires are made up of 4 items or sentences whose response format follows the Likert model of four scales (1. Strongly disagree, 2. Somewhat disagree, 3. Some agreement, and 4. I very much agree). The missing values have been assigned code 99. Eleven questions from the CENVE questionnaire and five from CCEAM were selected for this study (Table 1).

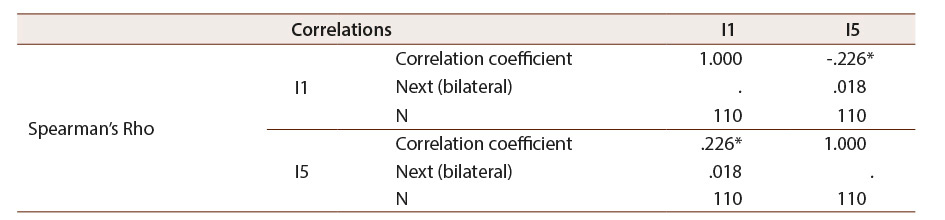

Table 1: Questionnaire on Educational Stereotypes of Older Adults (CEEAM) (I. 1-5) and Questionnaire on Evaluating Negative Stereotypes of Older People (CENVE) (I. 6-16)

Note: Own elaboration from the indicated instruments. The questionnaire used in this research was based on the CENVE questionnaire (Blanca Mena et al., 2005) and the FAQMH questionnaire (Montorio and Izal, 1991; Palmore, 1977).

Members of the research team applied the tool. With prior authorization, the scale was applied, during the same period of time, in the classroom and during regular academic hours. All participants were duly informed of the nature of the research, anonymity and confidentiality of the data collected was guaranteed.

The following section provides an impromptu analysis of the data collected from teachers in initial training. There were 16 Likert-type statements. The analysis of the quantitative data obtained in the study was done using the SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) (version 24, IBM SPSS).

Research Results

In the following lines we present the results obtained from the analysis of the data collected in the research carried out. We discuss the most relevant data that define the level of stereotypes of teachers in initial training present. To facilitate interpretation, the items have been grouped into the factors listed in Table 1, which has been entered above.

Educational Factor

The group of questions related to the Educational Factor is composed of 5 items dealing with the prescriptions that teachers in initial training have regarding the learning capacity and educational resolution of older adults.

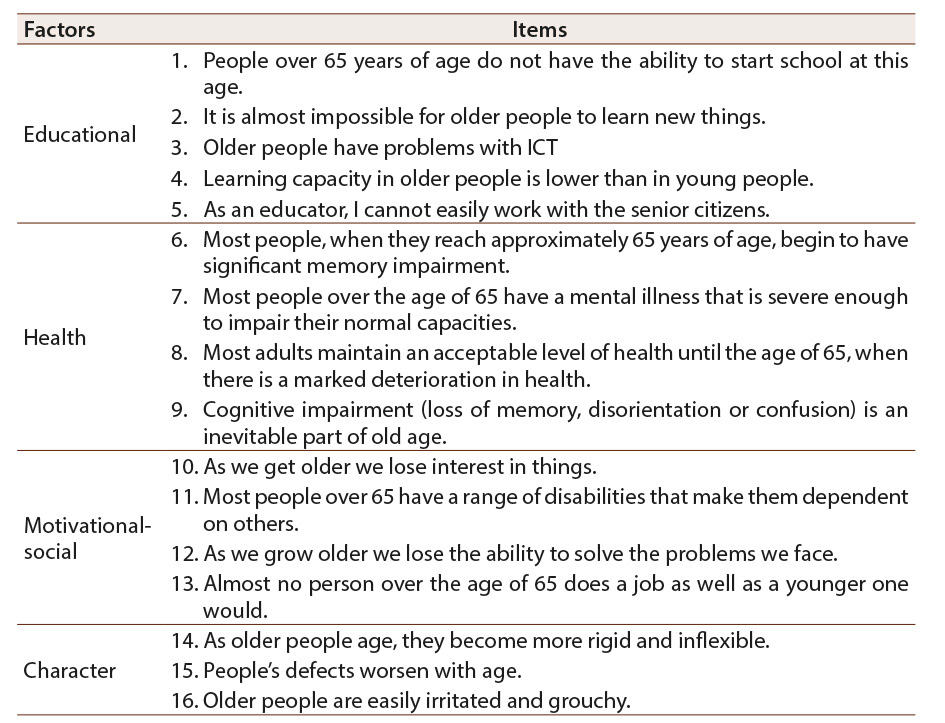

As can be seen in Table 2, there is a considerable number of teachers in initial training who agree (27.2%) with the affirmation that refers to the fact that those over 65 years old do not have the capacity to begin studying at those ages. A percentage that is slightly more than a quarter of the respondents surveyed. You can start studying at any time during your life cycle. Therefore, we found a moderate level of stereotype in 23.6 per cent of respondents and a high level of stereotype in 3.6 per cent of cases.

However, it is significant that for question 2 there is a 95.5 per cent, who point out that people can learn new things. Learning can happen at any time in life. In this sense, respondents showed a moderate level of stereotype at 3.6 per cent and a high level of stereotype at 0.9 per cent. This is the Educational Factor item where we find a lower level of stereotype (4.5%).

A learning process involving the use of new information and communication technologies (ICT), in which we find diversity of opinions. On the one hand, 26.4 per cent disagreed with the assertion that at certain ages they are beginning to have problems with ICT, compared to 50.5 per cent who said they agree with the assertion. In this sense, we find that opinions are divided between those participants who disagree or somewhat disagree (32%) and those who agree somewhat or fully agree (67.9%). Faced with the stereotype between the use of ICT and people over 65, we found a moderate level of stereotype among 50.5 per cent of respondents and a high level of stereotype in 17.4 per cent of cases. Within the Educational Factor, this is the item where we find the highest level of stereotype (67.9%).

As for question 4, 49.5 per cent are somewhat in agreement and 17.4 per cent fully agree that learning capacity in older people is lower than in young people, only 7.3 per cent say they are in complete disagreement and 25.7 per cent somewhat disagree. Learning ability is independent of age. Therefore, we found that there is a moderate level of stereotype in 49.5 per cent and a high level of stereotype in 17.4 per cent of cases. This is the second item with the highest level of stereotype in this factor.

As for their professional work with this group, 75.4 per cent indicate that they do not agree in any way with the fact that it will be difficult to work with older adults, as opposed to 24.5 per cent who consider that it will be relatively complex to work with this group. Educators, as professionals, must adapt to educational environments, including the users who take part in them, regardless of age. In this sense, 22.7 per cent of the answers have a moderate level of stereotype; together with 1.8 per cent have a high level of stereotype.

Table 2: Frequency measurements related to Educational Factor

Note: Own elaboration from the indicated instruments. The questionnaire used in this research was based on the CENVE questionnaire (Blanca Mena et al., 2005) and the FAQMH questionnaire (Montorio and Izal, 1991; Palmore, 1977).

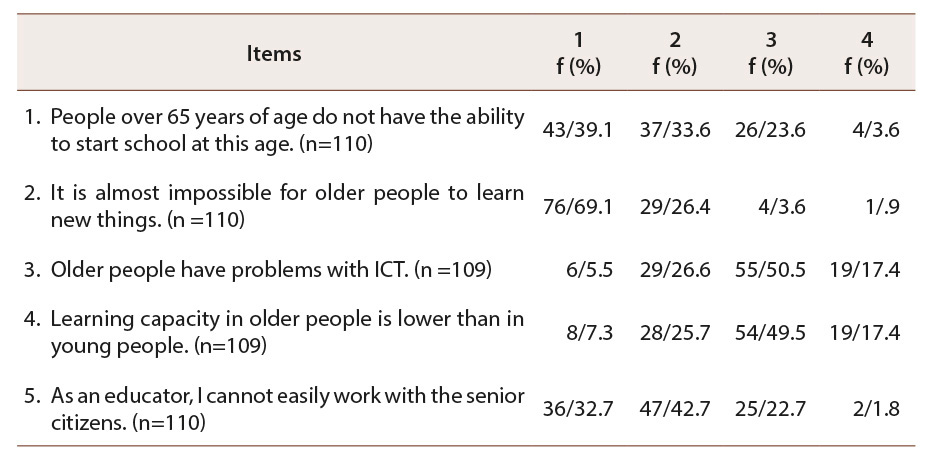

In the analysis carried out, similarities were found in the answers to questions 1 and 5. A 27.2 per cent of the participants consider that those over 65 years old do not have the capacity to start studying (P1). The 24.5 per cent indicates that group with which it will not be easy for him to work as an educator (P5). We have performed the non-parametric Spearman correlation, having found a significant correlation at the 0.05 level (bilateral) (Table 3).

Table 3: Correlations items 1 and 5

* The correlation is significant at level 0.05 (bilateral).

Note: Own elaboration from the indicated instruments. The questionnaire used in this research was based on the CENVE questionnaire (Blanca Mena et al., 2005) and the FAQMH questionnaire (Montorio and Izal, 1991; Palmore, 1977).

Health Factor

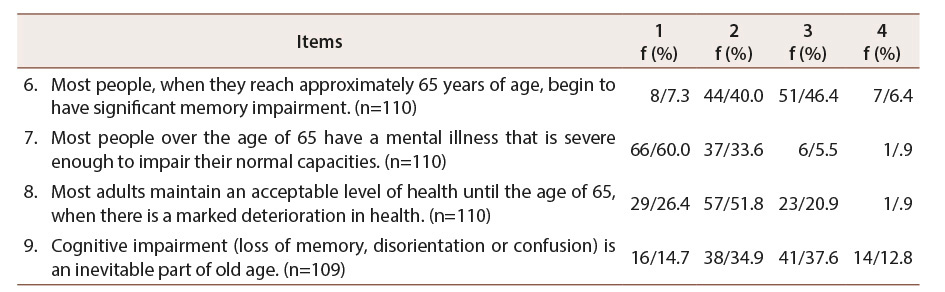

The group of Health Factor issues is composed of 4 items that address issues related to older adults, and express claims of impaired health, cognitive impairment and mental illness. Health Factor is made up of items 6, 7, 8 and 9, which were subjected to a descriptive statistical analysis of frequencies (see Table 4).

Table 4: Frequency measurements related to Health Factor

Note: Own elaboration from the indicated instruments. The questionnaire used in this research was based on the CENVE questionnaire (Blanca Mena et al., 2005) and the FAQMH questionnaire (Montorio and Izal, 1991; Palmore, 1977).

In item 6 Most people, when they reach approximately 65 years of age, begin to have significant memory impairment 46.4 per cent determines that Some agreement with this statement. On the other hand, 40.0 per cent consider that it is somewhat disagree. Therefore, 86.4 per cent of the surveyed population is based on the core values of possible responses. However, only 7.3 per cent consider the phrase as strongly disagreeing, and 6.4 per cent as very much agree. The fact of turning 65 is not associated with a significant deterioration in memory. In contrast to this stereotype, the figure is 47.3 per cent. Therefore, the percentage of respondents with stereotypes in this item is in the majority. A moderate level of stereotype is recognized in 46.4 per cent and a high level of stereotype in 6.4 per cent.

When the student body is questioned by item 7 most people over the age of 65 have a mental illness that is severe enough to impair their normal capacities 60 per cent of the respondents are positioned in option strongly disagreeing and 33.6 per cent consider option somewhat disagree. We can say that the student (93.6%) is opposed to the stereotype proposed. On the other hand, 5.5 per cent affirm some agreement, and 0.9 per cent point to option very much agrees. We see that the stereotype of having serious mental illness in people over 65 is still present in the respondents, but at very low levels. We found that the majority, 93.6 per cent, identify the stereotype. For this reason, we see that the relative percentage to the moderate stereotype level is 5.5 per cent and the relative percentage to the high stereotype level is 0.9 per cent. This is the Health Factor item where we find a lower level of stereotype (6.4%).

In relation to item 8 most adults maintain an acceptable level of health until the age of 65, when there is a marked deterioration in health, 51.8 per cent of students indicate option somewhat disagree, and 26.4 per cent indicate option strongly disagreeing. In other words, 77.2 per cent of the respondents opposed the stereotypical statement. However, 20.9 per cent indicate option some agreement and, visibly minority, 0.9 per cent indicates very much agree. The stereotype is to accept that from the age of 65 onwards there is a significant deterioration in health. In this sense, 20.9 per cent of those surveyed said that they had a moderate level of stereotype and 0.9 per cent that they had a high level of stereotype.

In relation to the affirmation Cognitive impairment (loss of memory, disorientation or confusion) is an inevitable part of old age, students are positioned in the central values (34.9% - Somewhat disagree; 37.6% - Some agreement). However, by including the four possible options, the respondents are distributed between the two axes (14.7% - Strongly disagreeing; 34.9% - Somewhat disagree; 37.6% - Some agreement; and 12.8% - I very much agree). We therefore face the stereotype of relating cognitive impairment to the aging process itself. In this sense, we find a moderate level of stereotype in 37.6 per cent and a high level of stereotype in 12.8 per cent of cases. Within the Health Factor, this is the item where we find the highest level of stereotype (50.4%).

From the data obtained on the health-related actor (Table 4) there are discrepancies in terms of the assertion made about memory impairment that most people begin to suffer when they turn 65. In that case, 47.3 per cent of the participants indicate disagreement or disagreement, compared to 52.8 per cent who indicate that they agree or strongly agree with this statement. When it is stated that most people over the age of 65 have a mental illness severe enough to impair their normal capacities, we find that there is a considerable number of participants who say they strongly disagree (60%) or somewhat disagree (33.6%) with this statement. In other words, 93.6 per cent con-sider that being older than 65 does not necessarily imply having a mental illness that impairs their normal capacities. When we analyze item 8, we can see that there is a considerable number of participants (51.8%) who disagree somewhat with the affirmation that is made about the deterioration in health that begins to suffer after crossing the threshold of 65 years, although 20.9 per cent indicates that they agree with this affirmation. However, only 0.9 per cent believes that this need not necessarily be the case. In question 9, 34.9 per cent of the participants are somewhat in disagreement with the assertion made about cognitive impairment, being considered as an in-evitable part of old age, while 37.6 per cent are somewhat in agreement with this question.

Motivational-social Factor

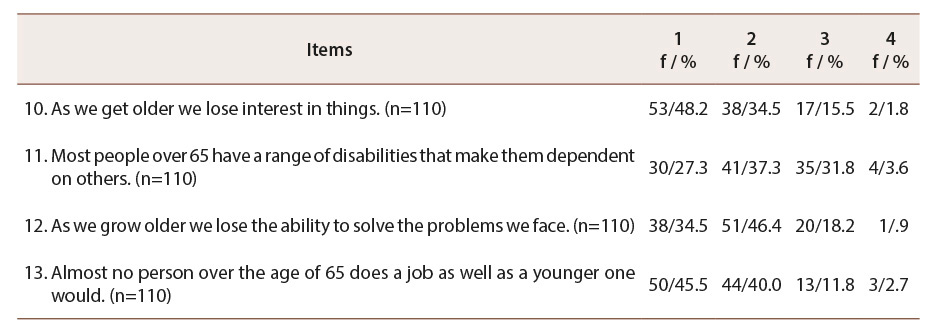

The questions relating to the Motivational-social Factor are composed of 4 items dealing with issues related to the lack of vital interests and the diminishing capacity to perform certain activities, and are made up of items 10,11,12 and 13, which were subjected to a descriptive statistical analysis of frequencies (see Table 5).

Table 5: Frequency measurements related to Motivational-social Factor

Note: Own elaboration from the indicated instruments. The questionnaire used in this research was based on the CENVE questionnaire (Blanca Mena et al., 2005) and the FAQMH questionnaire (Montorio and Izal, 1991;

Item 10 as we get older we lose interest in things shows how the student body positions itself against the stereotypical statement. 48.2 per cent say strongly disagreeing and 34.5 per cent point to option somewhat disagree. Nevertheless, 15.5 per cent indicate that they are some agreement and 1.8 per cent indicates very much agree. Interest in the things that people possess is independent of their age. In this sense, we found a moderate level of stereotype in the respondents at 15.5 per cent. Only 1.8 per cent shows a high level of stereotype. We can affirm that the stereotype of this item is identified as such by most of the subjects in the sample.

When we present the affirmation most people over 65 have a range of disabilities that make them dependent on others, 64.6 per cent is against. Therefore, we find a 27.3 per cent indicating that they are positioned in option strongly disagreeing and 37.3 per cent are located in option somewhat disagree. However, 31.8 per cent indicate that they are some agreement, along with 3.6 per cent that they say very much agree. Among those over 65 years of age, we find self-employed persons, dependents to a certain degree or dependents. However, we cannot associate being over 65 with dependence. The majority of respondents identify the stereotype (64.6%). On the other hand, we found a moderate level of stereotype in 31.8 per cent of respondents and a high level of stereotype in 3.6 per cent. Within the Motivational-social Factor, this is the item where we find the highest level of stereotype (35.4%).

In item 12 as we grow older we lose the ability to solve the problems we face the student body is shown opposite to the stereotype. Thus 46.4 per cent indicate somewhat disagree and 34.5 per cent strongly disagreeing. On the other hand, we find 18.2 per cent that considers some agreement and 0.9 per cent as option very much agree. Problem-solving skills are found regardless of a person’s age. Most of them (80.9%) were against the stereotype, 18.2% had a moderate level of stereotype and 0.9% had a high level of stereotype.

In the case of item 13 almost no person over the age of 65 does a job as well as a younger one would, the student body is against the stereotype. For this reason, the percentage among the values opposing the statement shown is higher. That is to say, 45.5 per cent are strongly disagreeing to this statement and 40.0 per cent are in somewhat disagree. The affirmative valuations with the statement shown are 11.8 per cent some agreement and 2.7 per cent very much agree. Older people have skills that enable them to function more efficiently at work than people who do not have the same level of experience. In this sense, 85.5 per cent of those surveyed recognize the stereotype. However, 11.8 per cent had a moderate level of stereotype and 2.7 per cent had a high level of stereotype. This is the Motivational-social Factor item where we find a lower level of stereotype (14.5%).

The results show that 48.2 per cent of respondents do not agree at all that the loss of interest in things has anything to do with ageing or turning age. 34.5 per cent said they disagreed somewhat with this issue. 15.5 per cent agree somewhat, so he thinks it is something that can happen. Only 1.8 per cent says they fully agree with the statement. As for the fact that being an older adult implies having a series of disabilities that oblige them to depend on other people for care, 27.3 per cent disagrees with this statement, along with 37.3 per cent who say they disagree somewhat. However, there is a broad spectrum of participants who say they agree somewhat (31.8%) or fully agree (3.6%). In other words, 35.4 per cent of the respondents therefore consider that the ageing process entails dependency. When it is stated that as we get older we have the perception that we lose the ability to solve the problems that come our way, 0.9 per cent of the students surveyed said they fully agree, along with 18.2 per cent who said they agree somewhat. However, 34.5 per cent state that they strongly disagree with this statement, along with a broad 46.4 per cent who say they disagree some-what. Exploring the answers obtained for the next question in which it is stated that almost no person over 65 years of age performs a job as well as a younger one would, we find that 45.5 per cent are in total disagreement and 40.0 per cent something in disagreement, constituting a majority of 85.5 per cent unfavorable to the affirmation. In the favorable positions, we find an 11.8 per cent that are recognized something according to the issue and a 2.7 per cent that is pronounced totally in agreement with the same one.

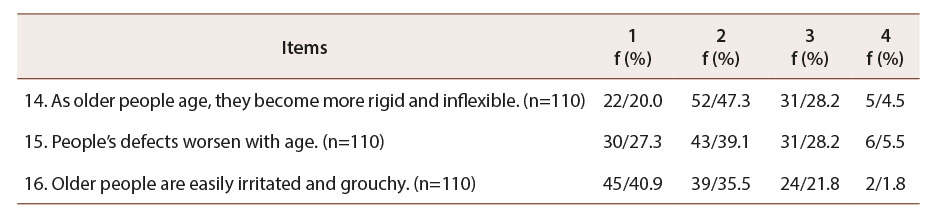

Character Factor

Character Factor issues address 3 items dealing with mental stiffness and emotional ability issues. It consists of items 14, 15 and 16, which were subjected to a descriptive statistical analysis of frequencies (see Table 6).

Table 6: Frequency measurements related to Character Factor

Note: Own elaboration from the indicated instruments. The questionnaire used in this research was based on the CENVE questionnaire (Blanca Mena et al., 2005) and the FAQMH questionnaire (Montorio and Izal, 1991; Palmore, 1977.

When students are consulted about their position on the as older people age, they become more rigid and inflexible statement and we get responses that oppose stereotyping. Thus, 47.3 per cent indicate that they are somewhat disagreement and 20.0 per cent indicate that they are strongly disagreeing with the statement. On the other hand, 28.2 per cent agree with some agreement and 4.5 per cent very much agree. The stereotype analyzed refers to the rigidity and inflexibility of people as they age. However, that a person’s character depends on his or her age is nothing more than a stereotype. No one becomes rigid and inflexible if he or she has never been rigid, just because he or she is 65 years old. Therefore, we can affirm that those who affirm to be some agreement (28.2%) present a moderate level of stereotype. Similarly, those who claim to be very much agree (4.5%) have a high level of stereotype.

Given the statement that People’s defects worsen with age; we observe that respondents are against stereotyping. In this way, 39.9 per cent indicate that they are somewhat disagree, 30 per cent indicate that they are strongly disagreeing, 28.2 per cent consider that they are somewhat agreement and 5.5 per cent comment that they are very much agree. As years go by, people’s defects don’t get worse. Birthdays alone are not an excuse for getting worse. Therefore, we are talking about a stereotype on the basis of age. In this sense, respondents show a moderate level of stereotype when they say that somewhat agreement (28.2%). In addition, 5.5 per cent of them are at a high level of stereotype when they say somewhat agreement. Within the Character Factor, this is the item where we find the highest level of stereotype (33.7%).

When we say that older people are easily irritated and grouchy, students take a stand against stereotypes. The highest values are a 40.9 per cent that indicates to be strongly disagreeing and a 35.5 per cent that points out to be somewhat disagree, followed by a 21.8 per cent that positions itself as some agreement, along with a 1.8 per cent that indicates to be very much agree. The association between older people and being grumpy or irritable is clearly a stereotype, as in the previous cases. Whether a person is irritable or not is a character trait, not their age. Of the three items analyzed, the students are shown with the least stereotypes. Even so, it shows a moderate level of stereotype of 21.8 per cent, together with 1.8 per cent, which is at a high level of stereotype.

In the analysis of the health dimension, it was observed that 32.7 per cent of the initial training teachers surveyed were in some way in agreement with the assertion that as we age we be-come more rigid and inflexible. A very similar percentage of favorable valuations (33.7%) are found in relation to the affirmation that defects worsen with age. As for the item older people are easily irritated and grouchy, we find that 23.6 per cent agree in some way, compared to 76.4 per cent who disagree with the statement.

Discussion and Conclusions

Once the results have been presented, we can affirm that stereotypes are present in the sample analysed. These results coincide with other research carried out in the field of stereotypes and initial training (Gutiérrez Moret & Mayordomo Rodríguez, 2019a, 2019b;

A detailed analysis allows us to affirm that twelve of the items analysed have a low level of stereotypes, two of the items are at a moderate level and two of the items show a high level of stereotypes. In this sense, the dimensions affected by items with a moderate level of stereotyping coincide with the health dimension, while the items with a high level of stereotyping are linked to the educational sphere. We found several studies in which it is related that the higher the level of education, the lower the presence of stereotypes towards older adults (Menéndez Álvarez-Dardet et al., 2016; Rodríguez Mora, 2020; Sánchez Palacios et al., 2009).

In the educational factor dimension, we found the following items at a low level of stereotyping: 1. People over 65 years of age do not have the ability to start school at this age; 2. It is almost impossible for older people to learn new things and; 5. It denotes that the students surveyed have sensitivity towards older adults in the educational field. Learning capacity in older people is lower than in young people and; 5. As an educator, I cannot easily work with the senior citizens. We understand that socially there is a tendency to consider older adults with low digital competences more typical of teenagers and young adults. In this line, a comparison is made between the learning abilities of young people and older adults, either in general or specifically with ICT, where respondents consider themselves in an advantageous position. Álvarez Hernández (2018) reaffirms this stereotype by highlighting that one of the factors that affect this aspect are those related to decrepitude, decadence and decline in various areas of the person.

Research carried out by Gutiérrez Moret and Mayordomo Rodríguez (2019a, 2019b) agree that stereotypes exist at the educational level. However, they justify them with the predisposition of teachers in training towards childhood stages. Nevertheless, this research team considers that among the items that show a low and a high level of stereotyping in the educational sphere, the training of the respondents in this study in “Educational research methodology and attention to diversity”, on “Family, school, interpersonal relationships and social change”, as well as “Teaching strategies and specific resources for attention to diversity”, which are subjects that form part of the curricula, come into play (Universidad de Sevilla, s.f.).

Most people over the age of 65 have a mental illness that is severe enough to impair their normal capacities and; 8. Most adults maintain an acceptable level of health until the age of 65, when there is a marked deterioration in health. This indicates an understanding that such issues may appear with age and/or worsen, but it is not a fact that can be generalised to older adults. Most people, when they reach approximately 65 years of age, begin to have significant memory impairment and; 9. Cognitive impairment (loss of memory, disorientation or confusion) is an inevitable part of old age. These items are related to memory, so social concerns about diseases such as Alzheimer’s may lead respondents to think that it is a health problem affecting older adults. It may also be linked to the fact that memory loss is socially accepted as a factor of ageing. These are commonly accepted stereotypes and it is not surprising that they appear in the research. Moreno-Crespo and Pérez-Pérez (2014) state that health is more vulnerable after retirement. In this sense, our study in relation to the health dimension is situated at an intermediate point with respect to other research using the same data collection instrument. In this sense, the studies by Rodríguez Mora (2020) and Gutiérrez Moret and Mayordomo Rodríguez (2019b) show low levels of stereotypes, while the study by Franco et al. (2010) shows high levels of stereotypes for this factor.

As we get older we lose interest in things; 11. Most people over 65 have a range of disabilities that make them dependent on others; 12. As we grow older we lose the ability to solve the problems we face and; 13. Almost no person over the age of 65 does a job as well as a younger one would. Although the level of stereotyping for this dimension is low, we find similarities with the results obtained in the study by Gutiérrez Moret and Mayordomo Rodríguez (2019a). As older people age, they become more rigid and inflexible; 15. People’s defects worsen with age and; 16. Older people are easily irritated and grouchy. We understand that in this dimension respondents see ageing as part of a natural process as a stage in life where other projects can be tackled, although this differs from other items in other dimensions.

It is interesting to note that the positive perceptions of the Education Factor contrast with the perceptions of the Health Factor in relation to items related to memory impairment and cognitive decline. These data coincide with studies that justify that the data related to the Health Factor show the presence of the most marked negative stereotype, due to the widespread conviction in society about the deterioration in terms of people’s health with increasing age (Aristizábal-Vallejo, 2004; Blanca Mena et al., 2005). However, the study conducted by Gutiérrez Moret and Mayordomo Rodríguez (2019a) with a sample of Primary Education teachers in initial training does not show negative stereotypes in the health dimension. This opens up a new line of research to address the differentiating criteria that lead to different assessments in different studies.

Trying to improve stereotypes in the population is a work of society as a whole that must transform the individual and the community. In this respect, teachers have an important role to play. Stereotypes in future teachers about older adults, as well as about older adults in training, raise the need to establish guidelines for action in educational and socio-educational contexts to try to reduce them (Gallardo et al., 2016; Gutiérrez Moret and Mayordomo Rodríguez, 2019a;

We find the need for further research on the topic, to analyse the synergies between the subjects that make up the curricula that favour less stereotypical perceptions of older people, and to extend the samples to university teachers and other education professionals.

Declaración de Material complementario

Este artículo tiene disponible, como material complementario:

-La versión preprint del artículo en https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4906578

References

Álvarez Hernández, H. J. (2018). Propuesta de intervención para reducir estereotipos y fomentar actitudes positivas hacia la vejez, en estudiantes de Enfermería de la UAEM, Ciclo Escolar 2017b [Proyecto Maestra]. Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública. http://repositorio.insp.mx:8080/jspui/bitstream/20.500.12096/7105/1/F055575.pdf

Amador, L., Malangón, J., & Mateo, F. (2001). Los estereotipos de la vejez. En A. J. Colom Cañellas & C.Orte Socías (Eds.), Gerontología educativa y social. Pedagogía social y personas mayores (pp. 55-75). Ediciones UIB.

Aristizábal-Vallejo, N. (2004). Imagen social de los mayores en estudiantes jóvenes [Tesis de grado]. Universidad de Salamanca.

Blanca Mena, M. J., Sánchez Palacios, C., & Trianes, M. V. (2005). Cuestionario de evaluación de estereotipos negativos hacia la vejez. Revista Multidisciplinar de Gerontología, 15(4), 212-220. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/28125856_Cuestionario_de_evaluacion_de_estereotipos_negativos_hacia_la_vejez

Campos Badilla, M. A. & Salgado García, E. (2013). Percepción sobre la tercera edad en estudiantes de primer nivel de la Facultad de Psicología de ULACIT y su relación con el desarrollo de competencias profesionales para el trabajo con adultos mayores. Revista Rhombus, 10(1), 1-30. https://www.yumpu.com/es/document/read/27499118/percepcian-sobre-la-tercera-edad-en-estudiantes-de-primer-ulacit/29

Canales Cerón, M. (Ed.). (2006). Metodologías de la investigación social. LOM Ediciones.

Cascone, C., de Cesare, G. R., & D’Elia, F. (2020). Physical education teacher training for disability. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 15(3), S634-S644. https://doi.org/10.14198/jhse.2020.15.Proc3.16

Cruz Díaz, M. del R., Moreno-Crespo, P. A., & Rebolledo Gámez, T. (2013). Formación universitaria de mayores. Un análisis del “Aula abierta de mayores” desde la perspectiva del alumnado. Revista Educativa Hekademos, 6(14), 41-51. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/ejemplar/476346

Da Silva Oliveira, R. C., Scortegagna, P. A., & Oliveira-Alves, F. (2017). educação permanente protagonizada pelo idoso na universidade aberta para a terceira idade/UEPG. Extensio: Revista Eletrônica de Extensão, 14(27), 19-33. https://doi.org/10.5007/1807-0221.2017v14n27p19

Duran-Badillo, T., Miranda-Posadas, C., Cruz-Barrera, L. G., Martínez-Aguilar, M. de la L., Gutiérrez-Sánchez, G., & Aguilar-Hernández, R. M. (2016). Estereotipos negativos sobre la vejez en estudiantes universitarios de enfermería. Revista de Enfermeria del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, 24(3), 205-209. https://www.medigraphic.com/cgi-bin/new/resumen.cgi?IDARTICULO=68023

Fernández-Ballesteros, R., Bustillos, A., Huici Casal, C., & Ribera Casado, J. M. I. (2016). Age Discrimination, Eppur Si Muove: (Yet It Moves). Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 64(2), 453-455. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13949

Fernández-Ballesteros, R., Olmos, R., Santacreu, M., Bustillos, A., Schettini, R., Huci, C., & Rivera, J. M. (2017). Assessing ageing stereotypes: Personal stereotypes, self-stereotypes and self-perception of ageing. Psicothema, 29(4), 482-489. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2016.314

Franco, M., Villarreal, E., Vargas, E. R., Martínez, L., & Galicia, L. (2010). Estereotipos negativos de la vejez en personal de salud de un Hospital de la Ciudad de Querétaro, México. Revista Médica de Chile, 138(8), 988-993. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0034-98872010000800007

Gallardo-Flores, A., Fernández, C., Sánchez-Medina, J. A., Alarcón, D., & Amian, J. (2016). Percepciones de niños y niñas sobre envejecimiento activo y saludable. En J. L. Castejón Costa (Coord.), Psicología y educación: Presente y futuro (pp. 878-884). ACIPE. http://rua.ua.es/dspace/handle/10045/64560

Gómez-Camacho, A., Núñez-Román, F., Hunt-Gómez, C. I., & Corujo-Vélez, M. del C. (2021). Preservice spanish teachers’ perceptions on linguistic sexism: Towards the integration of norm and GFL. Language and Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2021.1981926

Gómez-Carrasco, C. J., Monteagudo-Fernández, J., Moreno-Vera, J. R., Sainz-Gómez, M. (2020). Correction: Evaluation of a gamification and flipped-classroom program used in teacher training: Perception of learning and outcome. PLOS ONE, 15(10), e0241892. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241892

Gutiérrez Moret, M. & Mayordomo Rodríguez, T. (2019a). Edadismo en la escuela. ¿Tienen estereotipos sobre la vejez los futuros docentes? Revista Educación, 43(2), 363-374. https://dx.doi.org/10.15517/revedu.v43i2.32951

Gutiérrez Moret, M., & Mayordomo Rodríguez, T. (2019b). Age discrimination: A comparative study among university students. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 22(2), 62-69. https://doi.org/10.14718/acp.2019.22.2.4

Hernández Sampieri, R., Fernández Collado, C., & Baptista Lucio, P. (2006). Metodologías de la Investigación. Mcgraw-Hill.

Hill, M. M. & Hill, A. (2002). Investigação por questionário. Edições Sílabo.

Instituto de Migraciones y Servicios Sociales. (2002). Envejecer en España. II asamblea mundial del envejecimiento. Autor. https://www.oissobservatoriovejez.com/publicacion/envejecer-en-espana-ii-asamblea-mundial-sobre-envejecimiento/

Lasagni Colombo, V. X., Bernal angarita, R., Tuzzo Gatto, M. del R., Rodríguez Bessolo, M. S., Heredia Calderón, D., Muñoz Miranda, L. M., Palermo Guiñazu, N., Torrealba Gutiérrez, L. M., Crespo Tarifa, E., Gavira, G., Palacios, M., Villarroel Campos, C. I., Fahmy, W. M., Charamelo Baietti, A., & Díaz Veiga, P. (2013). Estereotipos negativos hacia la vejez en personas mayores de Latinoamérica. Revista Kairós Gerontologia, 16(4), 9-23. https://doi.org/10.23925/2176-901X.2013v16i4p9-23

Lucio-Villegas Ramos, E. L. (Coord.). (2011). Investigación y práctica en la educación de personas adultas. Nau Libres.

Matas Terrón, A., Leiva Olivencia, J. J., Franco Caballero, P. D., & Isequilla Alarcón, E. (2017). Representación social de los estudiantes de magisterio sobre los mayores: Un estudio piloto. Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Docencia (REID), (17), 61-78 https://doi.org/10.17561/reid.v0i17.2786

Melero Marcos, L. (2007). Modificaciones de los estereotipos sobre los mayores. En L. Álvarez Pousa & J. Evans Pim (Eds.), Comunicación e persoas maiores: Actas do Foro Internacional, Colexio Profesional de Xornalistas de Galicia (pp. 29-46). Colexio Profesional de Xornalistas de Galicia. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2651192

Menéndez Álvarez-Dardet, S., Cuevas Toro, A. M., Pérez Padilla, J., & Lorence Lara, B. (2016). Evaluación de los estereotipos negativos hacia la vejez en jóvenes y adultos. Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología, 51(6), 323-328. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.regg.2015.12.003

Montorio, I. & Izal, M. (1991). Cuestionario sobre estereotipos hacia la vejez [Edición experimental]. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.

Montoro Rodríguez, J. (1998). Actitudes hacia las personas mayores y discriminación basada en la edad. Revista Multidisciplinar de Gerontología, 8(1), 21-30. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317831616_Actitudes_hacia_las_personas_mayores_y_discriminacion_basada_en_la_edad

Moreno-Crespo, P. A. (2019). Educación y participación: ¿Cómo los participantes en aulas de mayores valoran sus habilidades para el desenvolvimiento académico? IJERI: International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation, (11), 137-151. https://www.upo.es/revistas/index.php/IJERI/article/view/3164

Moreno-Crespo, P. & Pérez-Pérez, I. (2014). Estereotipos sobre la jubilación en pretitulados universitarios: Proyecto de innovación docente. REIRE Revista d’Innovació I Recerca en Educació, 7(2), 53-70. https://doi.org/10.1344/reire2014.7.2724

Nava-Gómez, G. N. & Reynoso-Jaime, J. (2015). Conceptualización y reflexión sobre la práctica educativa en un programa de formación continua para docentes de educación media superior en México. Revista Educación, 39(1), 137-157. http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/revedu.v39i1.17862

Núñez Cortes, J. A., Núñez Román, F. y Gómez Camacho, A. (2021). Actitud y uso del lenguaje no sexista en la formación inicial docente. Profesorado. Revista de Currículum y formación del profesorado, 25(1), 45-65 https://doi.org/10.30827/profesorado.v25i1.13807

Palmore, E. (1977). The facts on ageing: A sort quiz. The Gerontologist, 17(4), 315-320. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/17.4.315

Pedrero-García, E., Moreno-Crespo, P., & Moreno-Fernández, O. (2018). Sexualidad en adultos mayores: Estereotipos en el alumnado universitario del grado de educación primaria. Formación Universitaria, 11(2), 77-86. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-50062018000200077

Pérez Serrano, M. G. (2004). Estereotipos, vejez y bienestar social. En M. G. Pérez Serrano (Coord.), Calidad de vida en personas mayores (pp. 51-76). Dykinson.

Pinazo-Hernandis, S., Agulló, C., Cantó, J., Moreno, S., Torró, I., & Torró, J. (2016). Compartiendo visiones sobre la educación. Un proyecto intergeneracional con séniors de la Universitat dels Majors y estudiantes de magisterio. Educar, 52(2), 337-357. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/educar.708

Portela, A. (2016). Estereotipos negativos sobre la vejez en estudiantes de terapia ocupacional. Revista Argentina de Terapia Ocupacional, 2(1), 3-13. https://www.terapia-ocupacional.org.ar/revista/RATO/2016jul-art1.pdf

Rodríguez Mora, Á. (2020). Estereotipos negativos hacia la vejez y su relación con variables sociodemográficas en una muestra de estudiantes universitarios. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 1(1), 63-70. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342089918_Estereotipos_negativos_hacia_la_vejez_y_su_relacion_con_variables_sociodemograficas_en_una_muestra_de_estudiantes_universitarios

Sánchez Palacios, C., Trianes Torres, M., & Blanca Mena, M. J. (2009). Estereotipos negativos hacia la vejez y su relación con variables sociodemográficas en personas mayores de 65 años. Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología, 44(3), 124-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regg.2008.12.008

Sanhueza, J. (2014). Estereotipos sociales sobre la vejez en estudiantes mayores: Un estudio de caso. Revista Internacional de Educación para la Justicia Social (RIEJS), 3(1), 217-229. https://revistas.uam.es/riejs/article/view/364

Serrate González, S., Navarro Prados, A. B. & Muñoz Rodríguez, J. M. (2017). Perfil, motivaciones e intereses de los aprendices mayores hacia los Programas Universitarios. Revista Educación y Desarrollo Social, 11(1), 156-171. https://doi.org/10.18359/reds.1863

Universidad de Sevilla (s. f.). Plan de estudios e información oficial del Título Grado en Educación Primaria. Universidad de Sevilla. Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación. https://www.us.es/estudiar/que-estudiar/oferta-de-grados/grado-en-educacion-primaria#edit-group-plani

Villas-Boas, S., Lima Oliveira, A., Ramos, N., & Montero, I. (2017). Educação intergeracional como promotora do envelhecimento ativo: Estudo de uma comunidade local. ReiDoCrea, 6, 105-119. http://hdl.handle.net/10481/45113

Weaver, J. W. (1999). Gerontology education: A new paradigm for the 21st century. Educational Gerontology, 25(6), 479-490. https://doi.org/10.1080/036012799267567

Artículo de la Revista Electrónica Educare de la Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica by Universidad Nacional is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Costa Rica License.

Based on a work at https://www.revistas.una.ac.cr/index.php/EDUCARE

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at educare@una.ac.cr