Revista Electrónica Educare (Educare Electronic Journal) EISSN: 1409-4258 Vol. 23(1) ENERO-ABRIL, 2019: 1-23

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15359/ree.23-1.4

URL: http://www.una.ac.cr/educare

CORREO: educare@una.cr

[Cierre de edición el 01 de Enero del 2019]

Characterization of Autonomous Work in a Chilean English Pedagogy Program: Teachers’ and Freshmen’s Perspectives1

Caracterización del trabajo autónomo desde la perspectiva de docentes y estudiantes de un programa de Pedagogía en Inglés en Chile 2

Caracterização do trabalho autônomo na perspectiva de professores e estudantes de um programa de Pedagogia em Inglês, no Chile 3

Roxanna Correa-Pérez

Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción

Concepción, Chile

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2035-4282

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2035-4282

María Gabriela Sanhueza-Jara

Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción

Concepción, Chile

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4037-8238

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4037-8238

Recibido • Received • Recebido: 10 / 05 / 2017

Corregido • Revised • Revisado: 17 / 07 / 2018

Aceptado • Accepted • Aprovado: 07 / 11 / 2018

Abstract: Autonomy in language learning is recognized as a basic skill language learners need to develop. This study describes the autonomous work activities university students carry out in a first-semester course of an English teaching program, and the amount of time they invest in each of these activities. Moreover, it describes the teachers’ perspective on students’ autonomous work. It is a descriptive mixed study with an exploratory scope. The study considers data generated through the application of a questionnaire and an in-depth interview to 48 freshmen from an English Pedagogy Program, as well as a questionnaire and a focus group applied to eight English teachers from the same program. The qualitative data were analyzed through content analysis method; and the quantitative data, through a frequency method of analysis. The analysis reveals that there is an imbalance between the time teachers estimate students devote to autonomous work and the real time students declare to invest in it. In relation to students autonomous work activities, it can be concluded that they concentrate on activities which are less stressful and the ones they do not need to interact with teachers. This study provides empiric information that could be useful to design courses that consider autonomous work.

Keywords: Autonomous learning; learning; autonomous work activities; autonomous work; university student.

Resumen: La autonomía es reconocida como una habilidad básica para el aprendizaje de idiomas. Este estudio describe las actividades de trabajo autónomo que estudiantes de universidades desarrollan durante una asignatura de primer semestre de Pedagogía en Inglés y el tiempo que le dedican a estas. También, describe la perspectiva del profesorado respecto al trabajo autónomo del estudiantado. Es un estudio descriptivo de carácter mixto con alcance exploratorio, que considera datos provenientes de un cuestionario y una entrevista en profundidad, aplicados a 48 estudiantes novatos de Pedagogía en Inglés, cuestionario y un grupo focal con 8 docentes de inglés del mismo programa. Los datos cualitativos se analizaron en base a análisis de contenido y los cuantitativos a través de análisis de frecuencia. Los análisis revelan un desbalance en el tiempo que el profesorado estima que el estudiantado dedica al trabajo autónomo y el tiempo real que el estudiantado declara invertir en este. En relación con las actividades de trabajo autónomo que el estudiantado realiza, se puede concluir que se concentran en actividades menos estresantes y aquellas en las que no necesitan interactuar con docentes.

Palabras claves: Aprendizaje autónomo; aprendizaje; actividades de trabajo autónomo; estudiantado universitario; trabajo autónomo.

Resumo: A autonomia é reconhecida como uma habilidade básica para o aprendizado de idiomas. Este estudo descreve as atividades de trabalho individual que os estudantes universitários desenvolvem durante um primeiro semestre de pedagogia em inglês e o tempo que dedicam a elas. Além disso, descreve a perspectiva do corpo docente em relação ao trabalho autônomo dos alunos. Trata-se de um estudo descritivo misto, com alcance exploratório, que considera dados provenientes de um questionário e uma entrevista em profundidade, aplicados a 48 estudantes novatos de pedagogia em inglês, um questionário e um grupo focal com 8 professores de inglês do mesmo programa. Os dados qualitativos foram analisados com base na análise de conteúdo e os quantitativos através de análise de frequência. A análise revela um desequilíbrio entre o tempo que os professores estimam que o aluno dedica ao trabalho autônomo e o tempo real que os estudantes declaram investir nele. Em relação às atividades de trabalho autônomo feito pelos estudantes, pode-se concluir que eles se concentram em atividades menos estressantes e aquelas em que não precisam interagir com os professores.

Palavras-chave: Aprendizagem autônoma; aprendizagem, atividades de trabalho independente; grupo de estudantes universitários; trabalho individual.

Introduction

This paper sets out to characterize autonomous work hours to the teaching and learning of English as a foreign language from Chilean English pedagogy teachers’ and students’ perspectives. Research about autonomous learning has become relevant in order to, on the one hand, understand the strategies or activities learners use to study outside the class and try to incorporate them in the classroom environment; and, on the other hand, to understand how learners can become more autonomous and responsible for their own learning process. Benson (2007), Hyland (2004), Little (2013), Oxford (2003), Ponton and Carr (1999), among others, have highlighted the importance of understanding the aspects that may foster or hinder autonomous learning. An important finding in a study carried out by Reinders and Balcikanli (2011) is that teachers and learners’ autonomy are interdependent; the author concludes that the lack of teacher’s knowledge and guidance will hinder learners’ autonomy. In Chile, English is taught as a foreign language; therefore, what students do outside the classroom constitute primary opportunities to practice the language. In this context, the aim of this study is to describe the activities English Pedagogy students do during the autonomous work hours stated in the syllabus of a first-semester course, and the amount of time they devote to autonomous work hours. It also describes the teachers’ perspective about the students’ time investment in autonomous work and the type of activities they get involved in. The findings of this research contribute to a better understanding of what autonomous learning is and implies in the field of teaching and learning languages.

Theoretical Framework

From the mid XX century a pragmatic and sociolinguistic view of language has emerged. It is considered as a creative activity of construction and negotiation of meaning oriented to communication. This concept of language has posed the development of communicative competence (CC) as the main aim for teaching and learning languages. Hymes (1972) defined CC as an ability to use the language to interpret meaning. Later, Bachman (1990), Canale and Swain (1980) and Hymes (1972) included the grammatical, social and psychological dimensions. In like manner, and from a sociolinguistic perspective, Saville-Troike (2005) summarizes CC as “what a speaker needs to know to communicate appropriately within a particular language community” (p. 100). This view implies that the speakers need to solve linguistic problems using their communicative skills to interact with others in authentic contexts. Consequently, it demands autonomous learners who can make decisions and be responsible of their own learning.

Autonomy is an aim that most educational programs declare to promote. The challenge is how to achieve this goal and the dilemma is how to know what teachers and students understand by autonomous learning (AL). Bandura (1986) referring to this concept states that the engagement of learners in different activities responds to cognitive processes derived from the information generated from personal actions or the actions of others. In 1987, Dickinson’s concept of autonomy corresponded to “total independent learning”, thus the learners were supposed to be responsible for their learning and the decision-making process associated. Moreover, this independency was only possible outside the classroom. Later, in 1990, the same author indicated that autonomy could happen inside the classroom. In this sense, social interaction with peers or teachers became a component of autonomy. Authors such as: Dam, Eriksson, Little, Miliander, and Trebbi (1990) define autonomy as “a capacity and willingness to act independently and in cooperation with others, as a social, responsible person” (p. 102). The relevance of this definition is that autonomy includes a social aspect as collaborative work.

Ponton and Carr (1999), Ponton and Rhea (2006) proposed a Model of Self-Directed Learning which considers two main components: (a) general and contextual applications and (b) learner self-directedness and self-directed learning. The first component refers to the beliefs, attitudes, desired and expected outcomes of the learner. Once learners identify the desired outcomes they are able to make the necessary decisions to them. Therefore, these decisions are more specific and oriented towards the desired outcomes. The second component of self-directed learning “represents what the learner intends to do and actually does with respect to the chosen learning activity” (Ponton and Rhea, 2006. p. 43). That is to say, self-directed learning is an intentional activity which aim is to achieve the desired outcome. Ponton and Carr (1999) carried out a study with a sample of 990 adults, they concluded that to promote AL teachers should primarily foster learners’ resourcefulness, understood as the ability to identify learning opportunities and resources available.

Some authors like Carr (1999), Derrick (2001), Ponton and Rhea (2006) also characterize autonomous learning as actions related to resourcefulness, initiative and persistence. Carr (1999) notes that resourcefulness can be identified by a series of co-ocurring behaviours: “ (1) prioritizing learning over things, (2) making choices in favour of learning when in conflict with other activities, (3) looking to the future benefits … undertaken now, and (4) solving problems (planning, evaluating alternatives, and anticipating consequences)” (p. 5). Ponton and Rhea (2006) propose 5 factors that foster initiative in autonomous learning: “goal-directedness, … active approach to problem solving, action-orientation, persistence in overcoming obstacles and self-startedness” (p. 44). Finally, Derrick(2001) points out 3 factors related to persistence: goal directedness, regulation and volition. In spite of the intentional characteristics of AL stated by these authors, the activities related to achieve the expected outcomes will not commence unless the learner has evidence of his or her own self-efficacy. Learners need to believe they have the capacity to carry out the activities assigned and evaluate if the expected outcomes are valuable enough for them.

In 2003, Oxford proposes a model of learner autonomy which considers four interrelated perspectives: technical, psychological, sociocultural and political-critical perspectives. In this context, autonomy can be seen as being aware of one’s goals for learning a language, as identifying preferred ways and feeling motivated to learn a language in a community.

Some features that authors seem to agree on AL are that it can be trained and it requires of certain conditions or context to be achieved, and that some learning activities may promote autonomous learning.

In the field of language learning the concept of AL has been studied to find out about the activities that promote autonomy in different language learning contexts. Scharle and Szabó (2001) refer to the types and sequence of activities to promote learner’s responsibility and autonomy in language learning. The first step is raising the learners’ awareness about their contribution to their own learning. The second, is the learners’ new attitude towards learning named changing attitudes. And the third corresponds to, transferring roles, in which students assume both more responsibilities and freedom of choice about their own learning, being able to teach themselves.

A different concept is out-of-class study time or out of class learning, proposed by Benson (2007), Fukuda and Yoshida (2012), Hyland (2004). According to Benson (2007), it refers to the activities students carry out to practice and use the language, studied in class, outside the class. Fukuda and Yoshida (2012) study suggests that students tend to engage in out-of-class learning activities more frequently than their teachers know. This study reveals that: “(1) clear course aims, (2) strong student–teacher relationships, (3) non-threatening classroom environments, and (4) interactive classroom procedures foster out-of-class study time” (p. 31). The authors add that the previous factors are dependent on students’ own initiative without relying on extrinsic motivation. Hyland’s study (2004) shows that students in Hong Kong spent a considerable time in activities outside the classroom, most of them “more private activities” as called by the author. The idea of private implies the engagement in receptive activities rather than productive ones.

Regarding teachers perspectives about students out of class work, Humphreys and Wyatt (2014) carried out a study with Vietnamese university learners and teachers from North America, Australasia and the United Kingdom found out that “learners’ uptake of autonomous practices seemed low” (p. 4) and teachers disapproved this passive learning behaviour. Complaints such as ‘the students do nothing outside of class” were commonplace among the typically native-speaker teachers.

Autonomous language learning (ALL) is also related to the selection and use of strategies so that apprentices take responsibility for their own learning. This suggests that students should reflect on how they learn languages and, consequently, perform actions that will help them to become autonomous learners.

Oxford (1999) proposes the five A’s concept of language learning autonomy based on: “Ability, attitude, + action = autonomy → achievement” (p. 111). According to Oxford (1999), these concepts are interwoven: the ability and the attitude of students towards taking an active role in learning a language without assistance promotes autonomy, which facilitates the students’ achievement. Thus, the attitude of students towards learning is closely related to motivation. Benson (2007) states that the link between motivation and autonomy is self –evident because “both are centrally concerned with learners’ active involvement in learning” (p. 29). According to the authors revised, this active involvement may be the key aspect which makes the difference between autonomous learning and the learners doing what they have been told to do. Benson (2001), considered autonomous learners as self – directed learners who are able to: define their learning goals and what to study, as a consequence learners are able to identify the techniques or methods needed to sudy and finally students do monitor their learning process. In sum, learners assume responsibilities and are in charge of their language learning process

Another theoretical stand about learner autonomy is Little’s (2013) who understands this concept as a matter of self-management which includes “continuous metacognitive engagement”. Little (2013) explains that autonomy in language learning is inseparable from autonomy in language use and adds that learning autonomy is promoted by a specific pedagogical approach which should consider the following principles: autonomy in target language use, learner involvement and learner reflection.

Referring to the impact of pedagogical factors in the promotion of learner autonomy (LA), Smith (2003) identifies weak and strong approaches to support LA. A weak approach assumes learners lack autonomy and therefore they need training, for example: pre-packaged curriculum materials are provided and technical practice is offered. A strong approach “co-creates optimal conditions for the exercise of their autonomy, engaging them in reflection on the experience” (Smith, 2003, p.131). According to the author, a ‘strong’ approach to the development of autonomy is needed, based on the learner’s existing autonomy, intrinsic motivation, metacognition strategies and contextual factors.

Method

This study is based on a quantitative-qualitative approach. Its aim is to describe students’ and teachers’ perspectives on (i) time invested in autonomous work and (ii) the type of autonomous work activities students declared to carry out. It is contextualized in a first-year English competence development course of an English Pedagogy program at a regional university in Chile.

Participant students were 48 freshmen with an age range 18 to 23 years old, who had graduated from Chilean public schools (49%), co-financed schools (46%) and private schools (5%) before entering the English Pedagogy Programme in 2015. Their CC in English diagnose informed that according to the Common European Framework (CEF) most of them were at A2 or B1 levels in vocabulary, grammar and receptive skills, and at A2 in speaking skills and B1 in writing skill.

Participant teachers were 8 EFL teachers (two of them with experience in languages teaching abroad) who have taught the subject for more than 3 years and shared the teaching load in the three existing sections of the course; therefore, they collaboratively revise, update and agree on the course syllabus activities and their timing.

Data collection

Data from students’ perspective were collected through a combination of a questionnaire and an in-depth interview. The questionnaire was answered by 48 students and aimed at gathering information related to the number of non-contact hours students spent during the academic semester in completing syllabus autonomous work activities: (1) assignment work, (2) study time / looking for information, (3) course platform revision, (4) E-portfolio updating, (5) language lab work, (6) teachers consultancy and (7) others. The in-depth interview aimed at gathering more specific information about the activities students declared to invest more time in. It was answered by a non-random sample of 10 students, 5 with a QPT level over 3 and 5 below 3. The aspects considered in the interview were: (1) specific activities to revise the course platform, (2) studying or looking for information, (3) activities not included in the course syllabus and (4) other activities they could carry out to learn English.

Data from teacher’s perspective were collected through an on line questionnaire and a focus group. The online questionnaire was answered by 8 teachers. It inquired about sufficiency of autonomous work hours, role of autonomous work activities and teachers’ opinion in respect to students’ accomplishment of the number of hours for autonomous work as declared in syllabus. The focus group included 6 teachers and consisted of 4 guiding questions related to: the sufficiency of the number of autonomous work hours in the syllabus regarding the course aims, the method used by teachers to estimate the time a student needs to dedicate to the different autonomous work activities, the teachers’ registration system of the autonomous work hours accomplishment, and extra autonomous work not stated in the syllabus.

Data analysis

In order to add validity and credibility to the study (Mackey, & Gass, 2005), data analysis underwent a triangulation process for both students’ and teachers’ perspective. Quantitative data from the students’ questionnaire and from the digitally recorded interviews were systematized and analysed for recurrent themes based on pre-determined categories aligned with the theory revised as well as emergent categories. The validation process of the coding was to pilot a sample of 1 interview and focus group. This procedure was carried out following Duijnhouwer (2010), who proposes to analyze small samples of the corpus by each researcher first and then audit these results within the research group. This procedure allowed the researchers to identify and correct possible errors or differences in the coding of the information in the categories and subcategories and stabilize the corpus. To establish the reliability and validity of the data classification, 2 external collaborators helped to code the information to compare their classification with the one of the researchers. Predetermined categories were: activities carried out to revise course platform, activities to study and look for information and activities not included in the course syllabus. The emergent category was extra activities to learn English. Qualitative data from the teachers’ questionnaire and focus group were systematized and analysed for recurrent themes. The questionnaire pre-determined categories were: sufficiency of time stated for autonomous work, role of autonomous work and students’ fulfillment of autonomous work hours. The focus group categories were: sufficiency of the number of autonomous work hours, extra autonomous work, registration system of the autonomous work hour’s accomplishment and method used by teachers to estimate students’ autonomous work. The analysis of the qualitative data followed coding and content analysis proposed by Miles and Huberman (1984) which considers the data collection, reduction and coding according to the study categories and drawing conclusions. Quantitative data was analysed applying frequency and percentage statistics techniques, which consisted in calculating and visually displaying the information collected (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2008).

Results

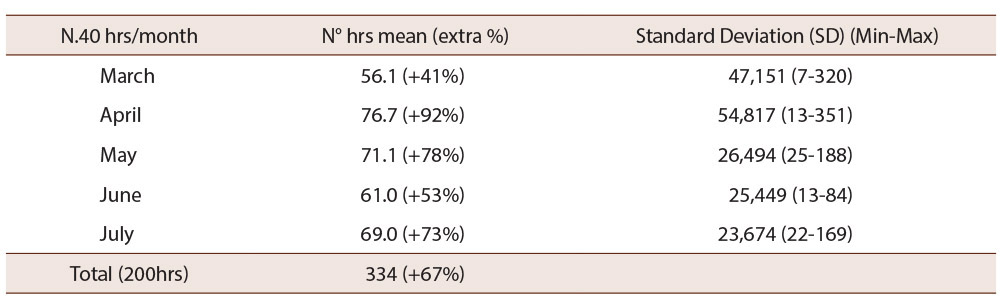

Results related to students’ data are presented first and teachers’ information is subsequently presented. Table 1 shows the results related to the number of hours students declared to invest during their autonomous work time from March to July, 2015.

Table 1: Autonomous work hours by month (elaborated by the researchers)

Results evidence that the average of AWH students declare to invest during the semester (334hrs), corresponds to 67% over the hours requested in the course syllabus which correspond to: 10 hours a week, 40 in a month and 200 in a semester. The results related to the total number of hours devoted to each activity during the semester are shown in Table 2.

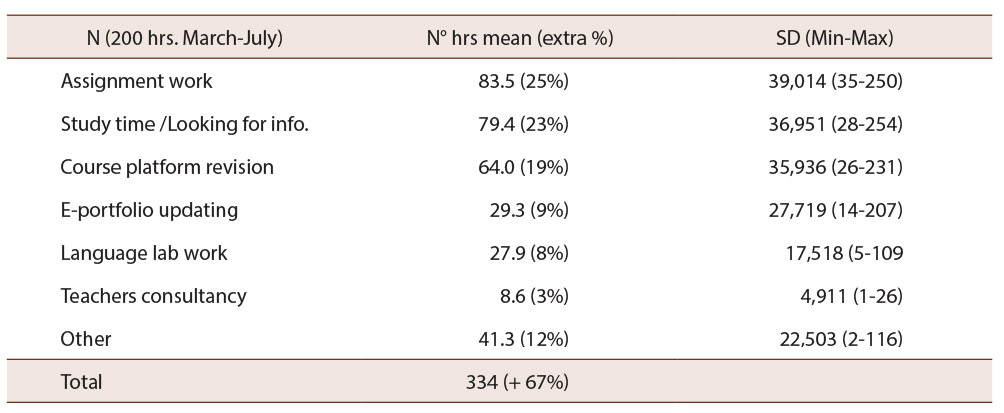

Table 2: Autonomous work hours by activities (elaborated by the researchers)

Results show that in all cases the number of AWH students declares to invest in the different AW activities exceed, in different percentages ranging from 3% to 25%, the time stated in the syllabus. Moreover, students do not distribute their AWH equally among the different types of activities. They dedicate most of their AWH to course assignment work, study time/looking for information and revising the course platform. The activities E-portfolio updating and Language lab work are activities students do in their AWH but are not their priority. Teachers consultancy is the activity with the least time investment; it represents just 3% over the estimated time in syllabus. Results evidence that students decide which activities they prefer to invest more time in. This choice of activities could be related to students’ motivation which, according to Benson (2001), is the core of AW considering that students’ decision of choosing what to study or revise makes them more autonomous. It is also evident that students devote more time to assignment work, which do not demand a face to face interaction. This could be explained by considering that freshmen have to face an English immersion context which is far different from their school experience. As a consequence, they could feel they are not able to interact with teachers in English, or they could feel ashamed of not having understood or of needing the teacher’s help. (Cook, 2001; Derrick, 2001; Oxford, 1999). The 12% allocated to “other” activities became a relevant aspect to find more about, therefore it was included in the interviews carried out.

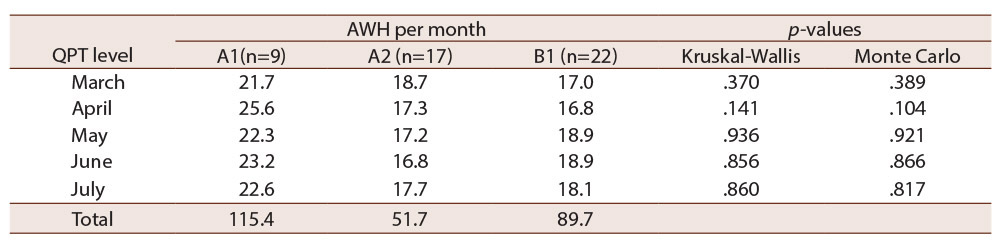

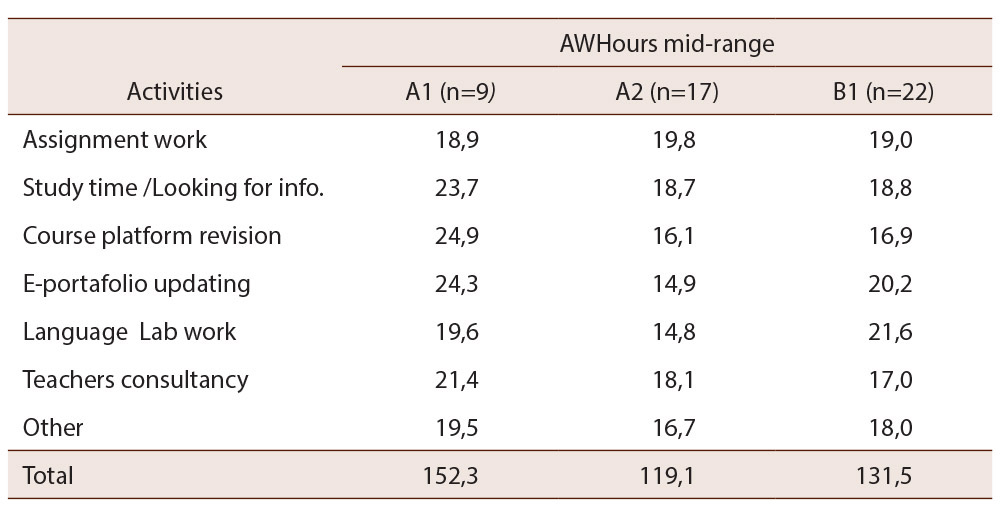

The data collected also allow relating the number of AWH declared by the students with their level of English proficiency. This information is displayed in Table 3.

Table 3: Autonomous work hours and level of English proficiency (QPT)(elaborated by the researchers)

Taking into account the p value for the Kruskal Wallis Test and the Monte Carlo procedure, it can be observed that there is no significant statistic difference in relation to the monthly number of AWH done by students when grouped according to their results in QPT. Therefore, the number of hours students dedicate to autonomous work is more or less similar, no matter the month of the academic semester. However, it can be observed that students with a lower level of English (A1) spend more time in their autonomous work (115 hrs.) than students with higher levels of English (A2 & B1).

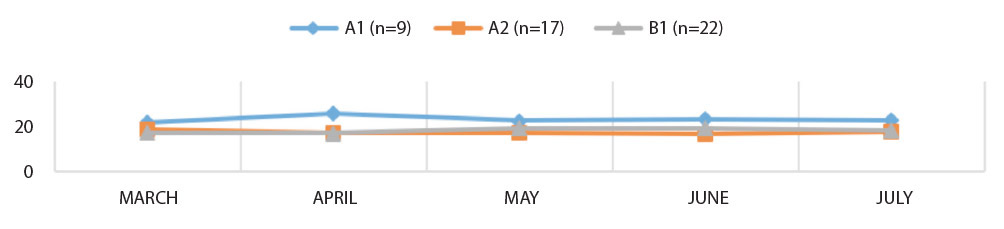

Figure 1: AWH/ Level of english proficiency (elaborated by the researchers).

Figure 1 shows that A1 students maintain a higher amount of AWH investment than A2 and B1 during the semester. A2 and B1 students work almost the same amount of AWH during the semester, showing slight differences at the beginning of the semester (A2 students work a bit more than B1) and between May and June (B1 students work a bit more than A2). It could be possible to say that students with a lower level of English in the QPT but higher hours of autonomous work, are more self-directed, more aware of the abilities they need to acquire and take responsibility for their own learning (Hasim, & Zakaria, 2016). If we analyze the number of hours in relation to the different activities and their level of English we can notice some differences as shown in Table 4.

Table 4: AWH in activities vs. level of English (elaborated by the researchers)

In terms of total number of hours A1 students work 28% more of AWH than A2 in the same period and 16% more than B1 students. This tendency could also be observed in Table 3; A2 students declare to work less hours than A1 and B2. Concerning the activities, A1 level students declare to allocate more time to a wider range of activities than A2 and B1 level students. The activities to which A1 level students devote more time are: course platform revision, E-Portfolio updating, looking for information and teachers consultancy. It is also interesting to notice that B1 level students invest more time than the students in the other two levels in language lab work. Besides, the activities to which A2 level students dedicate less time are: E-Portfolio updating and language lab work. It could be inferred that B1 level students do prefer to carry out more independent work at the lab, because as possibilities are immense and varied they can choose what to do.

Based on what Benson (2001) states, students who are more proficient (B1) are more self-directed and take more control of their own language learning process. According to Ponton and Carr (1999), once self-directed learners identify the desired outcomes they will make more specific, contextualized and oriented decisions towards these. To this respect, lab work offers them the possibility to choose the contents to study and the skills and methods to approach them, and also the possibility to monitor their own learning process through immediate feedback and the chance to give it a second or even a third trial. Accordingly, Derrick (2001) claims that the learner needs to evidence self-efficacy in order to initiate his way to achieve the expected outcomes.

As it was mentioned before, an in-depth interview was applied to a sample of 10 students to know more specific information about the activities they had declared to invest more time in when answering the questionnaire. In this sense, the interview was related to the following aspects: specific activities to revise the course platform, activities to study or look for information, activities not included in the syllabus and any other extra activities they could carry out to learn English. The results are displayed by each of these aspects.

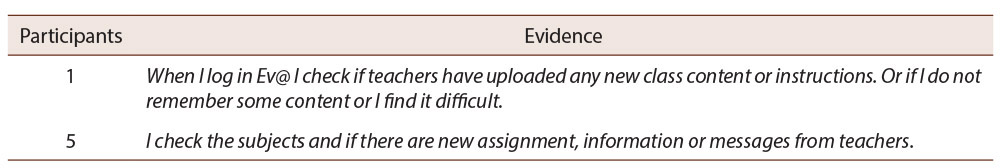

Specific activities to revise course platform

Considering that students declared investing an average of 64 hours in the semester to revise the learning virtual environment course platform (Ev@), it was important to ask the participants about the specific activities they carried out when revising this platform. Some of the evidence is shown in Table 5 below.

Table 5: Specific activities when revising course platform (Ev@)

Most students declare to revise if the teacher has uploaded a new material or instructions for the coming class, or if there is a new message from the teacher. Some of them declare they revise previous class materials or resources, topics they have not understood and look for documents to read and prepare for the following class. As it can be seen, the activities they declare to carry out are triggered by the teachers’ possible requirements. In this sense, Little (2013) points out that we could not expect otherwise if their previous educational experience has been entirely teacher lead. Moreover, the author adds that students believe good educational success depends on following the teacher’s instructions.

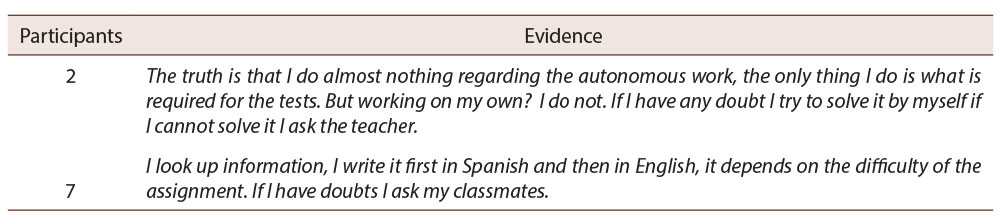

Activities to study or look for information

The average number of hours declared by participants in this aspect corresponds to 79.4 hours during the semester. Therefore, it became relevant to further inquire. Table 6 shows some of the participant answers.

Table 6: Activities to study or look for information

When students look for information, their search is mostly directed by the requirements of the assignments they need to fulfill and the evaluative tasks they have. Students follow the instructions given and, in case of doubt, they ask their classmates. Some students also declare that the use of Spanish (L1) or English (L2) depends on the degree of difficulty of the task assigned. It is also important to notice that one participant declares that he does not do any autonomous work, except when there is a test to prepare, and, if in this situation, he/she would ask the teacher only if he wasn’t able to solve doubts on his own. Even though the activities carried out are oriented to achieve the assignments, the way they fulfill these assignments is varied; therefore, it may be inferred that students are able to make the necessary decisions to achieve the outcomes. As Ponton and Carr (1999) note, once learners identify the desired outcomes their decisions are specifically oriented to achieve those outcomes.

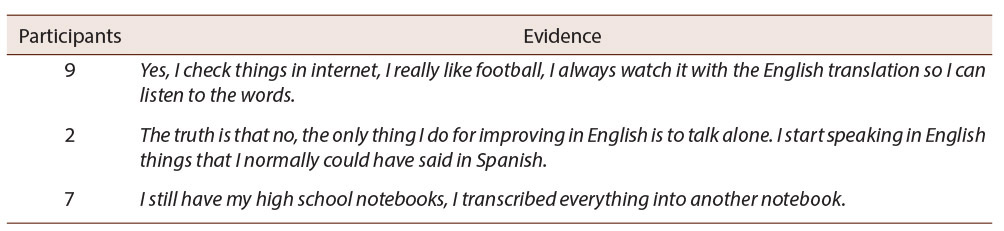

Activities not included in the course syllabus

The activities carried out by students but not stated in the syllabus were considered relevant to investigate by the researchers, because some authors indicate that one of the characteristics of autonomous work is that students make decisions about the type of content and activities to practice or study certain topics or abilities (Benson 2001; Hasim, & Zakaria, 2016). Examples of these activities are displayed in Table 7.

Table 7: Activities not included in the course syllabus

This aspect reveals the variety of activities students do to study or to foster their abilities and knowledge about the English language (L2). They revise internet looking for the topics they are interested in, one participant expresses that he learns English watching football in English. However, it is interesting to comment what P2 and P7 answered: the former practices the language by speaking English instead of Spanish no matter the situation and, the latter, uses her school copybooks to review different topics. These activities reflect students’ self-motivation and self-direction (Dickinson, 1987) in organizing their own work or study time.

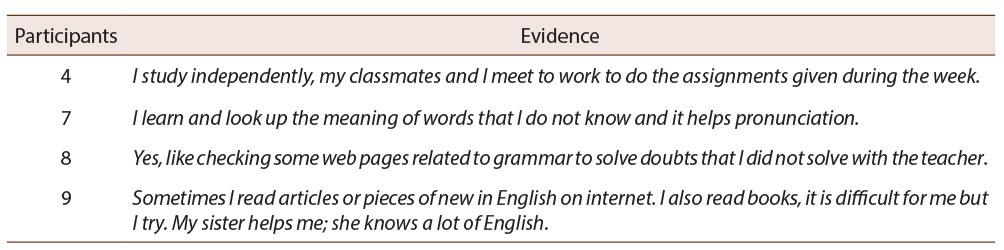

Extra activities

Extra activities relate to any activity students decide to carry out on their own to learn English. Some of the students’ statements are shown in Table 8 below.

Table 8: Extra activities

The activities declared by the students are varied, some of them declare to prepare assignments by working with their classmates while others on their own. Internet seems to be the main source to look for information together with songs in English, web pages to study topics they like and also checking new vocabulary. Some other participants declare to ask for help to relatives who know English and to read news in English. Maybe, it is in this category in which students show what they really do and the decisions they make to study or practice the language. According to Benson (2007), to work alone or with others does not define autonomous work. In fact, Dam (1995), Little (2013), Trebbi and Barfield (2009), define autonomy in cooperation and interaction with others. Thus, autonomous learning does not necessarily mean to work alone but to be in charge of one’s own learning and this could be a collective or individual action.

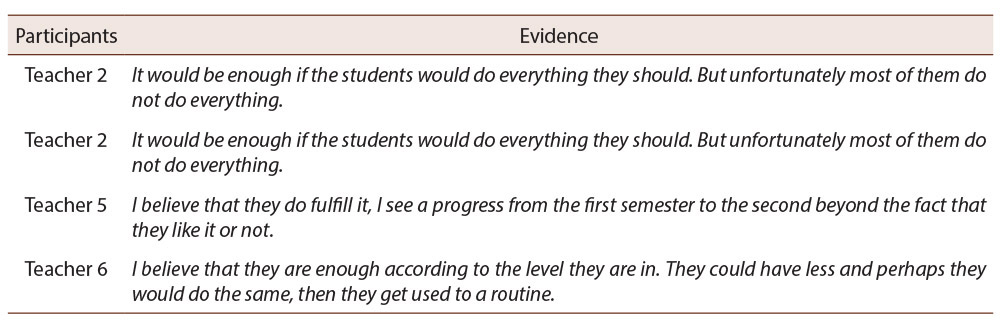

Results regarding teachers’ perspective about autonomous work for language learning will be presented in relation to the different aspects considered. When asked about sufficiency of autonomous work hours, some teachers informed the following; see Table 9 below.

Table 9: Sufficiency of autonomous work hours

Teachers’ opinions show a level of agreement; T5 and T6 explicit that the number of AWH is enough because they can see some results of this work by the end of the course. T6 adds that the time is appropriate for the students’ level, because this work outside the class becomes a routine and they get used to do it in the amount of time provided. T2, declares that the number of AWH is enough but that the problem is that students do not fulfill the number of AWH required for the course. When consulted for the reasons why students may or may not work the number of hours required, participants teachers expressed the following; see Table 10 below.

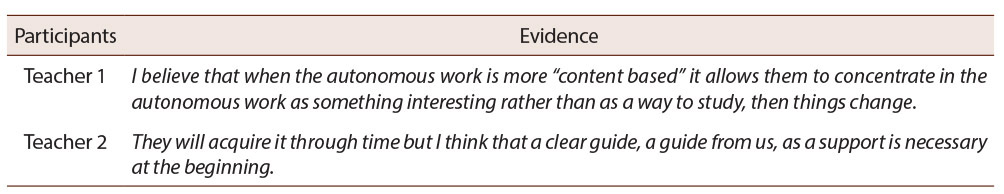

Table 10: Reasons for students completing / not completing required number of AWH

It is interesting to notice that teachers do see some kind of “hope” in students’ commitment to carry out the work in the assigned hours. They point out that if the assignment motivates the students they might be more willing to do it, especially if it is content based. In addition, T2 agrees that they have to guide students in this kind of work. To this respect Scharle, & Szabó (2001) mention that learning activities can promote autonomy by changing students’ attitude towards learning.

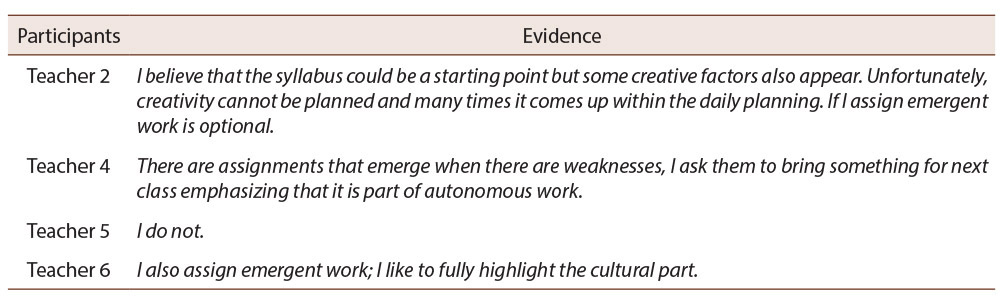

The second aspect discussed was about “emerging work” that is, assignments teachers ask that are not considered in the course syllabus. Some of the evidence is shown in Table 11.

Table 11: Emerging work

Most teachers state that they do give extra or emerging work except one of them (T5). The reasons for doing this are different; teachers creativity, keystone topics for teachers to be and to compensate some specific weaknesses. It is also interesting to notice that T4 declares to give extra work, but at the same time she tells the students that this is not part of AW. It seems that there is a confusion of concepts or it can be inferred that the teacher considers AW as a synonym of homework.

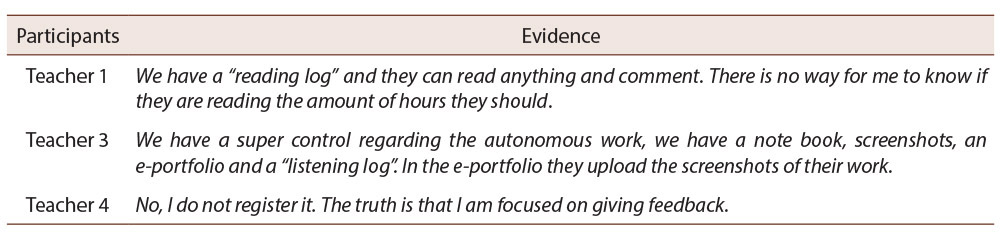

The third aspect consulted was about the way teachers registered the completion of AWH. In Table 12 some examples of the participant answers.

Table 12: Completion of AWH registering method

As it can be noticed, teachers do control de completion of AW except T4 who does not do it but explains that she/he provides feedback to the work carried out by the students. The way of checking completion is asking students to provide evidence of their work through reading and listening logs, and videos. Students are also asked to show some screenshots of the work developed in the language labs. This kind of control could be related to Smith’s (2003) idea of a weak approach to learning; in this context, pre-packaged curriculum materials are provided and technical practice is offered.

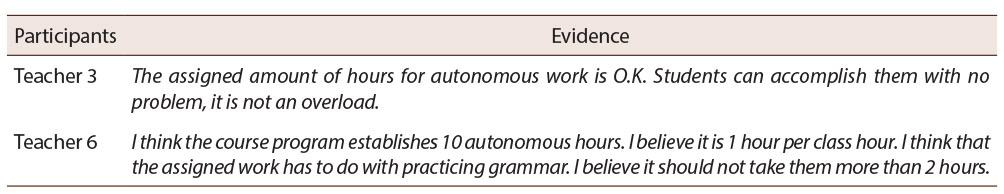

The fourth and final aspect discussed in the FG was about the way teachers estimate the number of AWH students need to carry out. Table 13 shows some of the teachers’ opinions.

Table 13: Estimation of number of AWH needed by students

Based on the previous evidence, it may be concluded that teachers think that the number of AWH are adequate and students can achieve them, without being a work overload. This belief may explain teachers’ decision to give students extra work, that is, work that was not previously considered in the course syllabus.

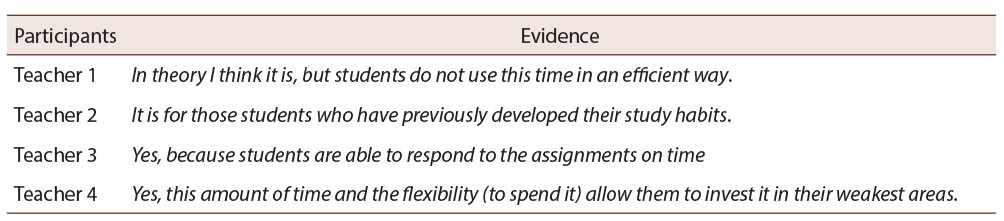

As it was mentioned before, the second instrument applied was an online questionnaire, answered by 8 teachers. This instrument inquired about: sufficiency of autonomous work hours, role of autonomous work and students’ fulfillment of autonomous work hours. The aspect of sufficiency was asked again in the on line questionnaire because in the FG most of the teachers declared the number of hours were not enough. The data collected with this instrument are presented by each of the aspects consulted. In the case of sufficiency of autonomous work hours teachers consulted stated what is displayed in Table 14.

Table 14: Sufficiency of AWH

It is evident that teachers agree on the fact that AWH are enough. However, they have some differences in the way they are used and the conditions that make them effective. For example, T1 states that it is enough but not properly spent and T2 declares that they are sufficient only in the case of students with acquired study habits. While T3 declares they know they are enough because students do the work assigned and T4 adds the aspect of flexibility of AWH, which can promote students work and in addition they may choose to work on their weakest linguistic aspects. This characteristic of flexibility of AW is also mentioned by Dickinson, & Carver (1980) as giving students opportunities to make decisions about when, where and what to work on.

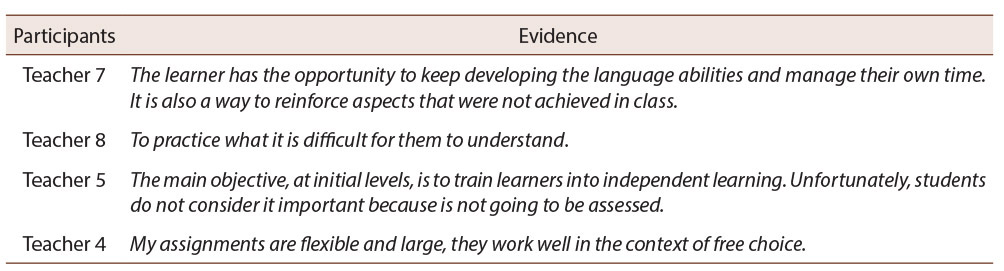

Referring to the role of autonomous work, teachers consulted agreed on the fact that these hours should be oriented to reinforce the learners’ linguistic weaknesses and they are an opportunity to promote an autonomous behaviour and self-monitoring. As it is shown in Table 15. T5 mentions the benefits of AWH but still thinks students still do not consider them relevant or meaningful for their learning.

Table 15: Role of autonomous work

It is also interesting to mention T4 who points out the free choice or students’ decision on what to work for autonomous learning. This is related to the concept of volition (Derrick, 2001).

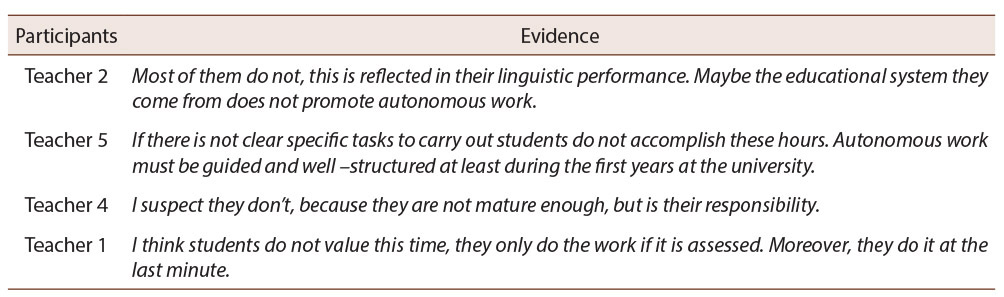

The third aspect discussed was students’ fulfillment of autonomous work hours. This aspect was included to inquire about teachers ‘view point about students’ behaviors in relation to AWH. Some of the evidence is presented in Table 16 below:

Table 16: Students’ fulfillment of autonomous work hours

Most teachers consulted agreed on the fact that students do not accomplish the number of AWH needed for this course. T2 states that this kind of work is not promoted at secondary school level; therefore, it becomes more difficult to be developed at tertiary level. This idea of the educational system not promoting autonomous learning is mentioned by Benson, & Voller (1997) who state that autonomy is an inborn capacity which is hindered by institutional education. T4 adds that this might be a problem of students’ maturity and as a consequence they do not assume responsibility for their own learning, a similar opinion is expressed by T1 who states that students do not “value” this option of having AWH to decide what to study. Some authors like Benson (2007) and Fukuda, & Yoshida (2012) explain that in general teachers are not really aware of the amount of AW students really carry out. Finally, T5 explains that AW should be “guided and well –structured” to be efficient, these ideas of AW is more controlled even some authors may not consider these conditions as AW. Fukuda, & Yoshida (2012) state that AW is based on students own initiative without relying on extrinsic motivation.

Conclusions and discussion

One important conclusion that could be drawn from this study is the imbalance between the time teachers estimate students need to devote to autonomous work asked in the syllabus and the real time students declare to invest on it.

A second conclusion is that teachers underestimate the time students need to complete autonomous work assignments; especially for the case of students with a very elementary level of English proficiency (A1), who devote more time to autonomous work than A2 and B1 students (Smith, 2003). When considering the monthly distribution of time for autonomous work it can be concluded that teachers think students tend to invest more time in autonomous work as the semester progresses. However, students show a systematic behavior in fulfilling autonomous work tasks.

Regarding teachers’ perspective of students’ autonomous work, they assume that students do not comply with the autonomous work hours required in the syllabus. This view of students as passive learners coincides with Humphreys and Wyatt study (2014), which evidence teachers’ complaints about learners’ autonomous behavior.

Teachers and students agree on the fact that tasks to promote autonomous work should be well structured and guided; this is aligned with Fukuda, & Yoshida’s research (2012) in the sense that autonomous tasks should have clear course aims.

In relation to autonomous work activities, it can be concluded that students get involved in decision making processes concerning the types of autonomous work activities they decide to carry out. Additionally, it could be said that they concentrate on activities which are less stressful, not that urgent and the ones they do not need to interact directly with teachers. It is worth mentioning the findings related to the varied ways in which students address tasks: working alone or with others, translating, internet search, listening to songs, news reading. This phenomenon coincides with Ponton and Carr (1999) in the idea that students are able to identify the outcomes and make different decisions on how to achieve the language learning goals.

As results show, students do look for help among peers and relatives. This reveals that students understand that autonomous work does not mean to work alone as Benson (2007) and Dam (1995) note. In addition, Ponton and Rhea (2006) propose the aspect of self- startedness in autonomous learning. This aspect can be related to the type of tasks student participants of this study carry out to fulfill autonomous work.

It is also possible to conclude that there are some differences on how the different proficiency level groups distribute autonomous work hours in the different types of activities. Students in the weakest level evidence being more dependent on the teacher’s guidance; whereas, more proficient students prefer to concentrate on more independent work. This difference relates to Benson’s (2001) theory about self-directedness and control taking in language learning by more proficient students.

Another finding is that teachers give work which is not considered in the course syllabus. This behavior reveals that teachers promote out of class study work instead of autonomous work. In spite of this tendency among the teachers consulted, and following Smith (2003), there is evidence of the existence of both, a weak and a strong approach towards learner’s autonomy. On the one hand, teacher participants who have had professional experiences with Australian, and Chinese language learners reflect a strong approach in which their teaching practices are based on the learner’s existing autonomy and motivation. On the other hand, teachers who reflect a weak approach, assume that Chilean students are not autonomous nor intrinsically motivated; therefore, they need to be trained and tightly controlled. This could explain the extra work some teachers demand from the learners.

In respect to the role of autonomous work, teachers agree on its importance for learning languages and consider it as an opportunity to promote an autonomous behaviour. Some authors point out that the final aim of developing autonomy is to become independent and a responsible learner (Dam, 1995; Little, 2013; Trebbi, & Barfield, 2009). However, some teachers do not consider autonomous work as a tool to support students in developing independency. This view reflects a more technical perspective of autonomy which is more oriented to the immediate fulfillment of certain tasks and the procedure to give account for them (Oxford, 2003). It is also worth pointing out that most of the teachers focus on controlling the completion of autonomous work activities, asking constant evidence of learners’ work. This way of monitoring learners’ autonomy is more technical oriented rather than more metacognitive oriented. Benson (2001), Smith (2003) understand metacognition as an important aspect in developing autonomous learning.

This study has offered useful information about autonomous work required in the syllabus of a specific university course. It informs about the students’ and teachers’ perspectives regarding time devoted to autonomous work, and types of autonomous work activities students privilege. It is a contribution to the evaluation and potential adjustment of the curriculum not only in the context of this research but also to curriculum design in any other similar context. Consequently, it would be recommendable for teaching training programmes to include an explicit autonomous work plan which should be consistent with course aims, structured on a systematic basis, time demand realistic, varied and flexible so as to give students some freedom of choice regarding students’ preferred learning strategies. In the context of future research, it would be relevant to explore students’ metacognitive processes when carrying out autonomous work.

References

Bachman, L. F. (1990). Fundamental considerations in language teaching. OUP Oxford.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Benson, P. (2001). Teaching and researching autonomy in language learning. London: Longman.

Benson, P. (2007). Autonomy in language teaching and learning. Language Teaching, 40(1), 21-40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444806003958

Benson, P., & Voller, P. (Eds.). (1997). Autonomy and independence in language learning. London: Longman.

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980) Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1(1), 1-47. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/I.1.1

Carr, P. B. (1999). The measurement of resourcefulness intentions in the adult autonomous learner (Doctoral dissertation), George Washington University, Washington.

Cohen, L., Manion,L., & Morrison, K.(2008). Research methods in education (6a ed.). New York: Routledge. Recuperado de https://islmblogblog.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/rme-edu-helpline-blogspot-com.pdf

Cook, V. (2001). Using the first language in the classroom. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 57(3), 402-423. doi: https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.57.3.402

Dam, L. (1995). Learner autonomy 3: From theory to practice. Dublin: Authentik.

Dam, L., Eriksson, R., Little, D., Miliander, J., & Trebbi, T. (1990). Towards a definition of autonomy. In T. Trebbi (Ed.), Third Nordic Workshop on Developing Autonomous Learning in the FL Classroom (pp. 102-103). Bergen: University of Bergen. Retrieve from https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/al/research/groups/llta/research/past_projects/dahla/archive/trebbi-1990.pdf

Derrick, M. G. (2001). The measurement of an adult’s intention to exhibit persistence in autonomous learning (Doctoral dissertation). Dissertation Abstracts International, 62(05), 2533B. (UMI No. 3006915). The George Washington University.

Dickinson, L. (1987). Self-instruction in language learning. Cambridge: University Press.

Dickinson,L., & Carver, D. (1980). Learning how to Learn: Steps towards self-direction in foreign language learning in schools. ELT Journal, 35(1): 1-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/XXXV.1.1

Duijnhouwer, H. (2010). Feedback effects on student’s writing motivation, process and performance (Tesis doctoral). Universiteit Utrecht. Retrieve from http://dspace.library.uu.nl/bitstream/handle/1874/43968/duijnhouwer.pdf?sequence=1

Fukuda, S., & Yoshida, H. (2012). Time is of the essence: Factors encouraging out-of-class study time. ELT journal, 67(1), 31-40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccs054

Hasim, Z., & Zakaria, A. R. (2016). ESL teachers’ knowledge on learner autonomy. In F. Lumban, F. Hutagalung, A. Razk, & Z. Hasim (Eds.), Knowledge, Service, Tourism & Hospitality (pp. 3-6). London: Taylor & Francis Group. Retrieve from https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781315617312

Humphreys, G., & Wyatt, M. (2014). Helping Vietnamese university learners to become more autonomous. ELT Journal, 68(1), 52-63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/cct056

Hyland, F. (2004) Learning autonomously: Contextualising out-of-classe language learning. Language Awareness, 13(3), 180-202. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09658410408667094

Hymes, D. (1972). The scope of sociolinguistics. Georgetown University Monograph (Series on Languages and Linguistics), 25, 313-333.

Little, D. (2013). Language learner autonomy as agency and discourse: The challenge to learning technologies. Dublin, Ireland: Trinity College.

Mackey, A., & Gass, S.M. (2005). Second language research. Methodology and design. New York. Routledge.

Miles, M .B., & Huberman, A. M. (1984). Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new method. USA: Sage Publications.

Oxford, R. L. (1999). Relationships between second language learning strategies and language proficiency in the context of learner autonomy and self-regulation. Revista Canaria de Estudios Ingleses, 38, 1999, 109-126. Retrieve from http://www.academia.edu/24255872/RELATIONSHIPS_BETWEEN_SECOND_LANGUAGE_LEARNING_STRATEGIES_AND_LANGUAGE_PROFICIENCY_IN_THE_CONTEXT_OF_LEARNER_AUTONOMY_AND_SELF-_REGULATION

Oxford, R. L. (2003). Toward a more systematic model of L2 learner autonomy. In D. Palfreyman, & R. C. Smith (Eds.), Learner autonomy across cultures: Language education perspectives (pp. 75-91). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230504684_5

Ponton, M. K., & Carr, P. B. (1999). A quasi-linear behavioural model and an application to self-directed learning. Hampton, Virginia: NASA Langley Research Center.

Ponton, M., K., & Rhea, N. E. (2006). Autonomous learning from a social cognitive perspective. New Horizons in Adult Education & Human Resource Development, 20(2), 38-49. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/nha3.10250

Reinders, H., & Balcikanli, C. (2011). Learning to foster autonomy: The role of teacher education materials. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 2(1), 15-25. Retrieve from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/mar11/reinders_balcikanli/

Saville-Troike, M. (2005). Introducing second language acquistion. Cambridge University Press, New York. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511808838

Scharle, Á., & Szabó, A. (2001). Learner autonomy. A guide to developing learner responsibility. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, R. C. (2003). Pedagogy for autonomy as (becoming-) appropriate methodology. In D. Palfreyman, & R. C. Smith (Eds.), Learner autonomy across cultures (pp. 129-146). London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230504684_8

Trebbi, T., & Barfield, A. (2009). Unveiling teacher and learner beliefs: An interview with Turid Trebbi. Independence, 47, 9-14. Retrieve from http://c-faculty.chuo-u.ac.jp/~andyb/Self/Beliefs.pdf

1 This research was part of DIN1515 Research Proyect from UCSC, Chile.

2 Investigación realizada en el contexto del Proyecto de Investigación DIN1515 de la UCSC, Chile.

3 Pesquisa realizada no contexto do Projeto de Pesquisa DIN1515 da UCSC, Chile.

Artículo de la Revista Electrónica Educare de la Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica by Universidad Nacional is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Costa Rica License.

Based on a work at http://www.revistas.una.ac.cr/index.php/EDUCARE

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at educare@una.cr