Revista de Historia

N.º 80 • ISSN: 1012-9790 • e-ISSN: 2215-4744

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.15359/rh.80.1.en

Julio - Diciembre 2019

Fecha de recepción: 29/05/2019 - Fecha de aceptación: 01/07/2019

INCLUSION POLITICS/SUBALTERNIZATION PRACTICES: THE CONSTRUCTION OF ETHNICITY IN VILLANCICOS DE NEGROS OF THE CATHEDRAL OF SANTIAGO DE GUATEMALA (16TH-18TH CENTURIES)

POLÍTICAS DE INCLUSIÓN/PRÁCTICAS DE SUBALTERNIZACIÓN: LA CONSTRUCCIÓN DE ETNICIDAD EN LOS VILLANCICOS DE NEGROS DE LA CATEDRAL DE SANTIAGO DE GUATEMALA (SIGLOS XVI-XVIII)

Deborah Singer *

Abstract: This article problematizes the notion of ethnicity underlying villancicos de negros of the Archdiocesan Historical Archive of Guatemala (AHAG). Although these are musical pieces that project the idea of social harmony in a festive context, the truth is that identities emerge in conflict with colonial power, based on an ambivalent discourse that consolidates and naturalizes racial stereotypes.

Keywords: Colonial Music; Villancicos de negros; Ethnicity; Subalternity; Cathedral of Santiago de Guatemala.

Resumen: Este artículo problematiza la noción de etnicidad subyacente en los villancicos de negros del Archivo Histórico Arquidiocesano de Guatemala (AHAG). A pesar de que se trata de piezas musicales que proyectan la idea de armonía social en un contexto festivo, lo cierto es que emergen identidades en conflicto con el poder colonial, sobre la base de un discurso ambivalente que consolida y naturaliza estereotipos raciales.

Palabras claves: música colonial; etnicidad; subalternidad; afrodescendientes; identidad cultural; discurso; historia; Guatemala.

“[...] that which is called the black soul is a white construction”.

Frantz Fanon1

Introduction

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the Cathedral of Santiago de Guatemala occupied a relevant place in the production of musical works.2 From the impact left by the Spanish musician Hernando Franco (1570), numerous maestros de capilla –chapelmasters– took to creating polyphonic works to grant enhancement to the festivities, attract the faithful to religious services and -at the same time- reaffirm the hegemony of the Church and the Crown.3 Within the varied musical production of the time, villancicos de negros, also known as guineos or negrillas, stand out. The characteristics of this subgenre of villancicos have been detailed in previous works,4 whose authors emphasize especially the construction of black people as a candid, innocent and joyful individual. In the case of Christmas negrillas, the theme revolves around a group of black men and women who head towards the Bethlehem Manger to cheer up the Child Jesus with their gifts, music and dances, amid an emotional display of Christian devotion.

Negrillas usually have a responsorial format to recreate the dialogue between the soloist and the choir; In addition, there are syncopation, onomatopoeias and different rhythmic combinations that, on the one hand, seek to generate a lively sound and, on the other hand, project the idea that black men and women have a “natural inclination” towards music and dances. The language used in villancicos de negros is a deformed Spanish in which letters are substituted or omitted and errors of conjugation, concordance, verbal tense, etc. abound. Since these are distinctive features that were attributed to all Afro-descendants, I will try to explore which categories come into play by configuring a notion of ethnicity in which skin color is the starting point for defining stereotypes of difference.

Sources

As a basis for analysis I will examine seventeen negrillas found in the AHAG. These are works for four or five voices, some of them with instrumental accompaniment parts: violins 1 and 2, bass, tubes, bugles and continuo. The pieces are as follows:

–Cavayeroz, tulo neglo ezté punctual5 –undated, Catalog n.º 188, 5 voices–, anonymous piece.

–Antoniya, Flaciquiya, Gacipá –undated, Catalog n.º 383, 5 voices–, by the Portuguese Fray Felipe de la Madre de Dios (1626- 1675).

–Pascualillo que me quieles –undated, Catalog n.º 233, duet–, by the maestro de capilla of the Cathedral of Puebla, Mateo Dallo y Lana (1650- 1705).

–Negliya que quele –1698, Catalog n.º 260, 4 voices– and Siolo helmano Flacico –undated, although the manuscript states that it was sung in 1738; Catalog n.º 264, 4 voices–, by the Spanish composer and maestro de capilla Sebastián Durón (1660- 1716).6

–Digo a siola negla –1736, Catalog n.º 636, single and 4-voice stanzas–, Jesuclisa Mangalena (1745, Catalog n.º 619, 5 voices– y Venga turo Flanciquillo –1746, Catalog n.º 618, 5 voices–, by the composer and maestro de capilla born in Santiago de Guatemala, Manuel Joseph de Quirós (?-1765).

–Turu turu lo nenglito –undated, Catalog n.º S900–, anonymous piece. On the front cover it reads Juguete de Navidad.

–Ah, siolos molenos –undated, Catalog n.º 419, 4 voices–, by Gabriel García de Mendoza (ca.1705-1738)

–Pue tambén somo gente –undated, Catalog n.º 796, 4 voices–, by Oaxacan composer Tomás Salgado (1698- 1751).

–Diga plimiya –1761, Catalog n.º 57A, 4 voices–, A siñola plima mia7 –1773, Catalog n.º 100, 5 voices–, Lo neglo que somo gente8 –1787, Catalog n.º 169, 5 voices–, Afuela afuela9 –1788, Catalog No. 174, 4 voices–, El negro Maytinero –undated, Catalog n.º 90, 5 voices– and Negros de Guaranganá –1788, Catalog n.º 179, 4 voices–, all villancicos by composer and maestro de capilla born in Santiago of Guatemala, Rafael Antonio Castellanos (1725- 1791).

Except for Negliya que quele –Sebastián Durón–, printed in Madrid in 1722, all the works are manuscript copies. I have chosen to preserve the original spelling, although on many occasions the composers are not consistent when trying to reproduce the Spanish spoken by Afro-descendants, so that the same word can appear written in different ways within the same negrilla.

Generalities of villancicos

The villancico is a literary and musical genre that flourished in Spain from the fifteenth century. These are songs that villagers –villanos– sang in vernacular, alternating the refrain –estribillo– with a varied number of stanzas –coplas–. In their origins the themes of villancicos were secular and made reference to the daily life of the people gradually religious motives were incorporated and, due to their great popularity, managed to introduce into the Church’s Offices in the place of the Latin responsories at Matins.10

The genre was adaptable to the specific needs of each liturgical occasion due to its great structural flexibility, which allowed contrafacta –the substitution of the text without a significant change to the music–, combining poetry, music and dance with elements of the mojiganga –a minor theatrical genre–.11 This is particularly visible in the villancicos de remedo, which seek to imitate in a humorous way different social groups, such as the letrados, sacristans, French, Portuguese, indigenous people, blacks, etc. The villancico integrated all the actors of society in the ephemeral and playful framework of the festivities. Nonetheless, as a literary genre, it always remained in a subaltern position which –according to Mabel Moraña–12 in turn similarly indicated the societal position occupied by the subjects whose voice the villancico projected. Because this article focuses specifically on the configuration given to Afro-descendants in the villancicos de negros, the approach will be from the perspective of ethnicity, specifically, the categories that intervene to define the difference from the other.

Stereotypes of the difference

Providing a definition of ethnicity is complex in the extreme because the concept is often used in a confusing manner and allows multiple approaches.13 Depending on the angle of analysis, each researcher focuses on specific aspects, such as physical appearance, ancestry, common history and narratives that give meaning to past events, place of origin, culture –that is, symbols and practices around which the group agglomerates–, affiliations, stereotypes, social exclusion; indeed, the list is long. One factor that has been frequently pointed out is the situational factor: people assume certain ethnicities depending on the situations they are confronted with in daily life.14 In other words, ethnicity is more a matter relative to the processes by which ethnic boundaries are created, than to the content of the ethnic categories themselves.15 However, phenotypic differences are usually the main marker of alterity which has resulted in the recognition of “races” as a subtype of ethnicity, regardless of how diffuse the line that defines and delineates them becomes.16 That is why some analysis frameworks propose the concept of racialized social systems, referring to the political, economic, social and ideological levels that are partially structured based on the location of the actors in racial categories. This involves forms of hierarchies that determine the way in which races are positioned and related.17

Classification schemes have always been linked to practices of colonization, slavery and servitude, since they establish patterns of action that are activated in certain circumstances, depending on whether they are “us” –power– or “they” –subaltern groups–. The culture of the other operates as a fundamental additional component in differentiation, since it permeates and institutionalizes social relations, consolidating certain hegemonies and establishing borders of exclusion. Thus, it is explained that the cultural difference is usually magnified: “After a society becomes racialized, a set of social relations and practices based on racial distinctions develops at all societal levels”.18

Galen Bodenhausen and Jennifer Richeson19 argue that racial differentiation brings collective representations of the other that translate into stereotypes; these circulate through the discourses, giving rise to narrative memories that create effects of the real with stereotyping results:

“A stereotype can be defined as a generalized belief about the characteristics of a group, and stereotyping represents the process of attributing these characteristics to particular individuals only because of their membership in the group. Whereas prejudice involves a global evaluative response to a group and its members, stereotyping consists of a much more specific, descriptive analysis”.20

The complexity of ethnicity and stereotyping is due to the fact that ambiguous and contradictory assumptions that influence the response to minorities prevail in any definition, so that behaviors that are inconsistent with previous expectations are often not recognized in the other.21 Otherness stands as a visible and predictable social reality that always gives rise to a new version of something known in advance. This repeatability –re-presentation– in changing historical circumstances creates an effect of truth that results in strategies of individuation and marginalization.22 Rogers Brubaker23 takes a step forward by calling into question the very notion of “ethnic groups” as an unobjectionable reality, that is, those delimited collectivities whose members recognize each other, share a corporate identity and have the capacity for concerted action.24 Thinking in terms of a group implies that invoking them “invites them to be” and with that they contribute to producing what is apparently being described; it is then another way of essentializing -and stereotyping- the other. This phenomenon is observed in the recognition of races; in reality races are not “in the world”, but are perspectives of the world, so that the task of any analyst should be to discover what leads ethnicity to be codified, what interests are at stake, what are the principles of differentiation of the social space that is being observed and what power structures prevail.25 The concrete fact is that Afro-descendant populations have been and still are classified according to social categories with a strong racial component: black, brown, mulatto, moorish, brown and zambo, among others.

From Guinea, Angola and Congo

It is known that most black Africans shipped as slaves to America came from the central-western region of Africa.26 Regardless of the linguistic-cultural differences of slaves –Mandinga, Yoruba, Bantu, etc.–, certain place names –Guinea, Angola, Congo– operated in the West as generics to represent the “place” of origin of black men and women. This characteristic can be observed in the villancicos de negros analyzed in this work. For example, the military troop cited in Afuela afuela is at the service of the King of Guinea.27 From Angola comes the group of black people involved in negrillas Digo a siola negla, Siolo helmano Flacico, Diga plimiya and Pue tamben somo gente, while the black people of Turu turu neglito come from Congo. There are some negrillas in which unknown places are mentioned: Guaranganá –in villancico Negros de Guaranganá– and Zambanbú or Carambú –in Diga plimiya–, which in the context of the villancicos de negros function as a synecdoque of Africa as a whole.28 The grouping of multiple communities into a single, large and homogeneous ethnic entity –Africa– results in the denial of local identity traits and the recognition of an alleged link between place of origin and racial difference. The truth is that in colonial society, classification modes prevailed that forced individuals to identify themselves in the category of blacks, even if they tried to counteract the stigma of blackness. Such imposed homogeneity left them no other identification options and their effects were subalternizing.29

Another marker element of ethnicity is the name that the western masters imposed on their African slaves. In addition to the symbolic violence that meant taking away their African-rooted name, this process of Christianization was naturalized in the negrillas through an avalanche of “typical” names given to black men and women, which in addition to appearing again and again, are deformed by replacing or omission of letters. This is an additional strategy to reinforce the idea of ascribing them to the group in question. Such is the case of the variants of Francisco –Flacico, Flancico, Flaciquilla, Flaciquillo or Flanciquillo–, Antonio –Antón, Antoniyo, Antona and Antonilla– and Gaspar –Gaspala, Gazipal, Gazipala, Gaspariya, Gaspá–. Other names that are repeated are Manuel, Pascual –Pascuá, Pascualillo– and Tomé –Tumé–. In the case of Jileta, Cazilda, Pantuflo, Maltin and Jesuclisa Mangalena, they appear only once in the negrillas reviewed in this work. It should be noted that the diminutives -such as Jorgiyo, Pascualillo, Antoniyo, plimiyo or negliyo- mark a paternalistic condescension that -in my view- constitutes another way of subalternizing, in a manner by which Afro-descendants are extended a child-like treatment.

Black speech modes

In the same way that names are transformed into stereotypizations, the omission or substitution of letters in the everyday speech of black people is another feature of ethnicity: they express themselves in a deformed Spanish already recognized by Spanish Golden Age authors as habla de los negros –Black speech Modes–. Quevedo points out with a certain dose of humor that to show knowledge of the Guinean language it was only necessary to replace “r” letters with “l”, and vice versa.30 To this we could add the errors in gender and number between articles and nouns, deficient verbal conjugation, omission of articles and prepositions, the loss of final consonants, etc.31

John Lipski32 points out that in the 16th century many of these dialectic/linguistic characteristics were common in the speech of Andalusia, Extremadura and the Canary Islands,33 which raises questions about the sociolinguistic and ethnolinguistic variants that were the product of socio-cultural interaction and that could demonstrate that the supposed homogeneity of the speech of Afro-descendants is rather a literary construction.34 In fact, the reviewed negrillas adhere to all the features mentioned above. For example, see Tiple I voice –the highest vocal register– of the first stanza of A siñola plima mia:

“Vamo al Poltalillo plesta

Llegalemo como etamo

Que si neglo ayá no vamo

No vale nara la festa”.

The systematic omission of the “s” is observed –vamo [vamos], etamo [estamos] –, the “r” is replaced by the “l” –neglo [negro]- and words are distorted –festa instead of fiesta–. Note also the association that exists between black men and women and joy. In Venga turo Flaciquillo there are substitutions of “d” for “l”: “Vamo aya, vamo aya/ oíl, oíl, oíl, milá, milá” –instead of “oid, mirad”– and in Pue tambén somo gente, they don’t know how to count correctly in Spanish: “Una, dosa, cuatlo cinco”. Because villancicos de negros were not created by Afro-descendants themselves –who were not the target audience either–, to deny them the possibility of speaking the hegemonic language correctly is to put them in a condition of meagerness and inferiority. This gives rise to a linguistic ethnicity that is mediated by the literate. Indeed, in the introduction of Negros de Guaranganá there is mention of a group of black men and women that begin to “grumble in their half tongue”.

In the negrillas the individual is transformed into a subject of a collective with uniform patterns of communication and that prevents Afro-descendants from introducing valid linguistic variants, according to their own cultural codes. Through this optic, the negrillas promote a discourse that guides the external perception about the ethnic minority, without considering the internal voices of that minority. This not only magnifies the difference,35 but also distorts communication with the other.

Between laughter and devotional expressions

When was laughter and joy transformed into constitutive elements of Afro-descendant ethnicity? The message that transcends is that the “natural” mission of them is to entertain the crowd. In fact, villancicos de negros usually express a permanent joy that manifests itself in laughter, onomatopoeic games or jitanjáforas36 that generate a cheerful and lively sound. For example, in Negliya quele, blacks sing: “Zezú, zezú, aleglia zezú, nos da nuezoz Reyes, zezú, zezú”. Also, in Siolo Helmano Flacico, the interjections “Acha á, acha é, ay Jesú Malia y Jusé, Malia and Jusé, uluá, ulué, alalilayle” stand out.

In some cases, the laughter is caused by embarrassing situations experienced by black men –in Afuela afuela and Turu turu lo Neglito one of them is bitten by a mule– or because some dare to place themselves in a condition of superiority with respect to their peers. In El negro Maytinero, tata Pascual -an old man who is described as an fiscal37 of some place- pretentiously gives himself the idea of being learned in grammar –“Griamatrica”– laws, music and Latin.38 That is why Pascual pretends to rehearse the Matins for Child Jesus with “Psamo and Antiphinine” –that is: psalms and antiphons–, but the choir of black men do nothing but laugh at him:

“Quien, quien

Ja ja ja ja ja,

No puere tata Pascua

Polque pala sel cantola

E menestel la solfeona

Ja ja ja ja ja

Y que risa nosra”.

Tata Pascual becomes irritated and silences them with indignation:

“Que Sofeona ni Sofíta,

caya tus voca bobita (…)

quere uté cayá, burego (…)

que a mi nengún bufarón

que me avía de burá

quando emu sabiro e ceto,

sendo como so tan preto,

que toro puero enseña,

yo sabe muy bie baylá”.

To be a singer, one must be acquainted with solfège, that is, be familiarized with the principles of Western musical theory, something that –according to the text– is out of reach for black men. In this particular case, what is at stake is the impossibility of accessing a specific field of knowledge as a consequence of belonging to a subaltern ethnicity. The lack of musical competence makes the group not take tata Pascual seriously, who rebels and affirms that being prieto –black– is not an impediment to instruct. Finally, he is left but to recognize that the only thing he knows how to do is dance and thus reinforces the stereotype associated with black people. As a counterpart, it could be argued that the corrupted Latin prayer recited by tata Pascual -”Gloria Patri ra Firio e ro Pripritu Sianto, Oygaro uté Vitatorio que e cosa re Pugatorio”- could indicate a sort of irreverence that subverts the prevailing order.

In the negrilla Antoniya, Flaciquiya, Gacipá, a group of black men dialogue with a black woman who suffers the effects drunkenness from the previous night:

“- Qué yo so

- ¿Qué?

- una siola

- Jijí

- malquesa de Sanguanguá

- Jajá

- y muy honrala

- Jijí, Jajá

(Mucho me duele la cabeza)”.

It is likely that contact with the white elite would awaken in this woman unrealizable aristocratic pretensions, which arouses the teasing by other black men and women. The scene also highlights frustrations arising from gender and class conflicts; since ethnicity is historically constructed and connects with other categories of difference –precisely of class and gender– these are ignored to create the idea that “negros” form a homogeneous group that is integrated into the Christian community on an equal basis. With this it is possible to see that the categories that intersect to define an ethnicity imposed from outside are diverse, although the racial category has a preponderance over all others: the protagonists assume their identity as “blacks”, which sometimes operates as revindication and other times as negotiation with the elite and their cultural models.

At this point it is necessary to stop and direct attention to the ways in which Christian devotion is displayed in the negrillas. The proclamation of Christianity as true faith means for black men and women the possibility to reach an advantageous position which they do not squander, as it allows them to dignify themselves as human beings who are on the right side of morality:39 they are good because they have faith and they have faith because they are good. When faith is strong, the signs of alterity are blurred, and black people are also allowed to define the ways in which they manifest their devotion. See for example the third stanza of Afuela, afuela:

“Adoramo al Niño Dioso

é también, a la Siola

é con toniya de Angola,

le ploculamo reposo,

duelme el Niño donoso,

plemiando la devosiona,

de lo Neglo y bona fé”.

Child Jesus is worshiped with cultural practices from Africa; as compensation, He will restore justice in the world. The Christ-centered narrative is the starting point for anchoring in the collective memory the idea that, in a state of poverty and exclusion, faith is the way to be saved. In Lo neglo que somo gente it is denounced to Child Jesus the vexations to which they are victims:

“Mi amo está un coxo,

y me haze el también,

pulque so su Neglo,

andal en un pié,

llevole a que Niño,

ya que es Justo Juez,

o mi incoge a mi,

o le sane a el,

que con er pie bueno,

es piol que pata”.

Since the Church sponsors the creation of these villancicos, the latent conflict between masters and slaves is neutralized through laughter, in addition to the consolidation of the figure of Christ –“justo Juez”– as a pillar of Christianity and restorer of social peace. In Ah, siolos molenos one of the black men offers Child Jesus his yearly wage ––pala que puela rescatal al Neglo”–, while another surrenders himself as an offering –“Pulque deya se silva le llevo tura mi pelsona, ni meno ni ma” – in a kind of hopeful self-sacrifice.

To be “black” stands as an antithesis of the whiteness of Jesus, which is constantly equated with light and purity. This dichotomy between whiteness and clarity as opposed to blackness and sin forces black men and women to constantly negotiate the boundaries of their ethnicity: although their skin is black, they try to prove that they have a white soul. A whitening attempt is made by adopting white culture to be socially admitted. In A siñola plima mía, the female pastor asks permission to go to the Manger of Bethlehem and tries to hide the color of her skin behind the whiteness of the sheep:

“Siola blanca no nos dexa,

digámosla a la Siñola

que si negla la Pastola,

tenemo branca la oveja”.

In the case of Digo a siola negra, black man protests the negative prejudices attributed to the color of his skin: “Mi Bien, el neglo es pulquien, le, le, al mundo has viajaro, mi bien, que nos dice alguien, le, le, que es neglo el pecaro”. In the same way that sin is black, blackness is conceived as a –black– disease. In stanza 4 of Cavayeroz, tulo neglo ezté puntual it reads: “Ben puriera e Niño, fa mi re, nacel neglo ya, zalambalapá, que ha de sanal nuestla negla enfelmedá, la, sol, fa”.

While skin color prevents Afro-descendants from constructing themselves as human beings with full rights, faith is presented as a hopeful route to whitening, although, in the end, it will always be impossible to achieve. The result is a constant displacement of the borders of ethnicity that is negotiated day by day through devotional expression.

However, it is difficult to affirm that black people fully internalize hegemonic discourses, especially when they resent that they are restricted from the identity options to which they can ascribe.

Threatening Troops

The expression of faith in Christ was not enough to vanish the threatening imagery that circulated around black people during the colonial era. Their arrival in Central America went hand in hand with the arrival of the conquistadors. The abolition of indigenous slavery in 1542 led to the granting of licenses and, subsequently seats, for the importation of African slaves,40 although we must not forget that an important contingent entered through smuggling. According to the census carried out in Santiago de Guatemala in 1604, some 7.000 people lived in the city; of these, 1.390 were black slaves, 225 mulatto slaves, 380 free mulattos and 10 free blacks.41 There is no clear data regarding the total number in Central America, but it is estimated that during the entire slave trade period they may have reached 21.000.42

For local indigenous people, black men soon revealed themselves as servants –and accomplices– of colonial power. At the beginning of the 1570s, the rural communities of the Santiago Valley of Guatemala wrote to the king to denounce the abuses and mistreatments they suffered from Spanish officers, city residents and their mestizo and black servants.43 This is expressed by the indigenes of Barrio de la Merced, who complain that the black slaves of the oidors of the Real Audencia forced them to sell horse forage – “rastrojo” – at a lower than market price:

“–Here is the suffering of when the oidors impoverished us, when they came to ask us to sell them forage. We do it, and they don’t give us its value. We are also mistreated by their black [slaves]. We no longer have land to procure forage to sell. It is very little with what we live. It is our affliction”.44

Later, in Memoria 4 it is denounced that “[…] en la carcel nos afligen los negros, los españoles y los mestizos, allá nos pegan”.45 [“[…] in prison we are afflicted by blacks, Spaniards and mestizos, they beat us there”.] This situation lasted until the dawn of Independence. On the visit that Archbishop Pedro Cortés y Larraz made to the diocese of Guatemala –1768-1770– he observed that in San Cristóbal of Totonicapán there was a black man in the square who grabbed the hands of the indigenes while they were whipped. The reason for this was that the Alcalde Mayor –chief local executive– sought to cause more dejection in indigenous people by having them seized by a black man.46 Severo Martínez Peláez points out that in 1811 an indigenous riot broke out in Patzicía because the tribute was collected with great rigor by a mulatto henchman servicing the Alcalde Mayor.47 In summary, despite the segregation policies that the Crown had provided because of the bad influence it attributed Spaniards, “negros” and mestizos on the indigenous population,48 the norm was never met. This generated interaction spaces that gave rise to castes known as zambos, which contributed to enriching the multiethnic profile of the Central American isthmus.

The increase in the importation of African slaves was directly related to agricultural needs –especially the production of sugar in the mills of the Dominican order and the production of indigo– mining and domestic service. Many slaves were even trained as artisans. It should be noted that in Guatemala the Spanish judicial system offered slaves legal spaces to defend their rights and buy their freedom. In fact, the majority managed to save money and, with the support of family networks, managed to obtain manumission.49 With the course of time there was a constant increase of free black men and mulattos who had enough freedom of movement and in some way or another integrated into Guatemalan society. Nonetheless, this did not minimize the segregation and social exclusion policies of which they were victims. In the Ordenanzas de Indias,50 details are given of the infractions that made them deserve punishment: fleeing, drinking, engaging in gambling, generating altercations, etc. Whether they were black slaves or free blacks, the violation of these norms increased distrust of them, making them look like a group prone to disorder, pillage and rebellion.51

In the mid-seventeenth century the traveler and English Dominican friar Thomas Gage wrote the following about slaves residing in indigo plantation estates: “Aunque estos no tienen otras armas que un machete […], sin embargo son tan desesperados, que muchas veces han causado alarmas a la ciudad de Guatemala, y se han hecho temer de sus mismos amos”. [“Although these have no weapons other than a machete […], however they are so desperate, that many times they have caused alarms in the city of Guatemala, and have scared their own masters”.]52 When Archbishop Pedro Cortés y Larraz visited the Dominican estate of San Jerónimo, he observed that “[…] hay esclavos que trabajan con perfección todo género de oficios necesarios, como albañilería, carretería, carpintería y fundición de metales para caldera y cuanto ocurra” [“[…] there are slaves who work to perfection all types of necessary trades, such as masonry, carriage making, carpentry and metal smelting for boilers and whatever else is required”].53 On the other hand, when it comes to black men or free mulattos who resided in the villages, their position was different. About the villa –town– of San Vincente the following was stated “los negros, mulatos y ladinos llevan una vida perversa y abandonada, sin temor de Dios ni del rey” [“blacks, mulattos and ladinos lead a perverse and abandoned life, without fear of God nor the king”].54 The prelate concluded that so many excesses could only be controlled by “sacando tantos negros, mulatos y ladinos, que ya abruman el reino o poniéndolos en más sujeción” [“expelling the so many blacks, mulattos and ladinos, who already overwhelm the kingdom or putting them under more subjection”].55

Despite these contradictory images regarding Afro-descendants, many were recruited to integrate armed militias.56 In fact, mulatto companies were urged to be formed, although the use of weapons by slaves, mulattos and mestizos was prohibited because they caused quarrels and became dangerous for their Spanish masters. In the course of the 18th century the Bourbons reorganized the militias of the kingdom of Guatemala, partly to cope with the advance of the English in the Caribbean, but also to stop the hostile incursions of the misquito zambos.57 This is how the Reglamento of 1755 contemplates the formation of a battalion of mestizos and mulattos, although by then they already represented a significant number in the militias, which assured them some prestige and integration in colonial society.

How do these militias of blacks and mulattos relate to the “troops” that emerge in the negrillas? The truth is that there is no relationship. The text strips them of any war allusion from the moment in which it is established that their only task is to pay homage to Child Jesus in the Manger of Bethlehem. This illustrates the way in which phenotypic differences become the main marker of otherness, regardless of how diffuse the segregation line becomes. Let us see some examples. In the negrilla Venga turo Flanciquillo, blacks trooped into the Manger to dance Matachines.58 In Pascualillo que me quieles, black men are ordered to form an armed squad “de tura la gente negla, y vengan malchando turitos a pliesa [a prisa] con las caravuzas [arcabuces]”. There is also a military troop in Afuela, afuela, which requires passersby to make way for the King of Guinea.

It has already been noted that the black troop marching to Bethlehem to worship the Child Jesus is commonplace in villancicos de negros. Nonetheless, I would like to persue Afuela afuela where the black troop tries to impose on the whites the –absurd– prohibition of sneezing when the King of Guinea passes by:

“Como lo branco estornura,

luego embalgamo tambaco,

entlamole ben a saco

como la Plaza de Bura,

no tenen casa segula,

ni vale pedil peldon

y apelan a San Joseph

le, le, le, ay Kirié,

ay Kirie, Kirieleyson.

Achí, achí,

Caya, caya beyaco,

Que te embalgalemo tambaco”.

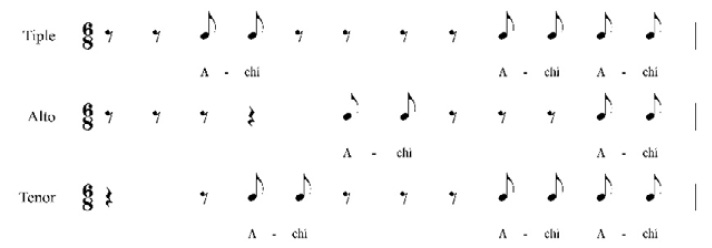

The text points to two threats aimed at whites: seizing their tobacco and “entrar al saco” The Diccionario de Autoridades of 1732 defines entrar a saco as a violent looting raid, “haciendo los soldados pillage de quanto encuentran en las casas y vecinos” [“making the soldiers pillage of whatever they find in houses and neighbors”]. Considering that in the colonial era fugitive blacks did form true militias dedicated to pillage, the image evokes a latent fear that –once again– is nuanced in the context of the celebration with the support of music. Although the white “bellaco” dares to sneeze, the intercalation of sneezes distributed in the three singing voices ends up giving the scene a cheerful and playful character:59

Image 1

Source: transcript by M. M. José Andrés Saborío.

The topic of sneezing also appears in the introductory section of Diga plimiya. In this case the group of blacks sings a tune to Child Jesus: “y aunque estornuden cantando, Señore, nadie les toca” [“and although they sneeze singing, Lord, nobody touches them”].

Music and dances

Music at the festive level lowers the tension of social conflict. Although there existed some degree of familiarity with the music that the African slaves performed in the streets of the cities, both the diversity of the musical practices of African origin and the functions that their music fulfilled –ceremonial, social, initiation, etc.– became gloom. Experience shows that certain textures and sound combinations were coded as typical of black people,60 which was embodied in the negrillas using dialogue, alternating voices, syncopation, hemioles, suspensions, and various combinations of rhythmic patterns.

Here it is necessary to focus for a moment on music graphic signs. The villancicos de negros of this work dating from the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th century are written in white mensural notation, have transposition clefs61 and 3/2 time signature. Such is the case of Cavayeroz, tulo neglo ezté puntual, Pascualillo que me quieles, Negliya que quele and Siolo helmano Flacico. In the negrillas by Manuel José de Quirós there are different notation systems: Jesuclisa Mangalena and Venga turo Flanciquillo represent what remains of modal thinking –the old musical notation–, while in Digo a siola negla the modern system –6/8 time signature– prevails. In the last period of the 18th century Rafael Antonio Castellanos definitely adopted modern notation and modern harmonic practice, developing compositional procedures adjusted to the tonal system. Thus, we see -for example- that the particellas are in natural clefs62 and the section changes are usually accompanied by a change of time signature –3/8, 6/8, 3/4–.

Music provided a common space that favored hybridization processes. For example, it is worth mentioning the presence of musical instruments of diverse origin, such as the guitarilla –guitaliya–, bandurria –bandurriya–, rabel –rabé–, violín –viorín– and violón –viorón–. In the group of wind instruments there are flutes –flauta, flautos, flautiya–, tubes –tompleton– and bass, although the most frequently mentioned instruments are percussion: drums –tamboritiyo, tamboril–, sonajas –zonagillas–, whistle, tambourine and adufe –arufe–.63 While European instruments predominate, some of them are of Arabic origin and others constitute local variants of African instruments. In Turu turu lo nenglito the group of black men and women present Child Jesus with “sonaja, chinchi, natambo, adufe y cascabé”. The black troop in Digo a siola negla offers Child Jesus a glorious dance with the “las zonagillas, pitos panderos y flautos”. In the negrilla Afuela afuela there is a display of chordophones:

“Manda Reye Gazipala

que Neglo vamo de gala

en Plussission al Pultál,

a cantal, con sonaja e guitaliya,

e cantemo tonadiya,

e que saltemo e baylemo

en lo Poltal de Belé,

con bandurriya y rabé”.

It should be noted that the instruments mentioned in the text do not necessarily coincide with the instrumentation that the composer created for the negrilla in question. Castellanos usually adds a part of violin –I and II– and continuo. Some pieces incorporate bass or horn –trompas–, although the fact that no more instrumental parts have been found so far does not constitute irrefutable proof that these were not present at that time.

Dances and musical genres of African origin have an important place. In Venga turo Flanciquillo it is announced “tocaremo la turumbella, cantaremo la zanguanguá”; in Cavayeroz tulo neglo esté puntual the chant says “bueno za, bueno za y turo lo Neglo bolvamo a entoná, zulumbulupé, pol fa mi re, zalambalapá, pol la sol fa”; finally, in Lo neglo que somo gente they sing “qui si haga, y mas que palesca, barumbá, barumbá, barumbára”. In the case of Venga turo Flanciquillo, the onomatopoeias ze, ze, ze and chi, chi, chi simulate the noise produced by the crossing of swords made by those who dance.

It is observed that the elements indicated mark the cultural difference and show how music reaffirms the criteria to define ethnicity. Note that in Diga plimiya there is a negative perception of white music:

“Cuando lo branco intenta,

con voze destemplaro,

al Infante alegraro,

hace a lo pleto aflenta,

pues canta impeltinente,

con tlizte muziquiya”.

Despite this, they later express pride because of their knowledge of western musical genres, however, –once again– the mistake in pronouncing their names reveals a pretentious ignorance that situates them again in a condition of inferiority: minuets –minuete–, arias –alie–, tonadas or tonadillas, ensaladas –ensarara–, canciones –cansioncilla–, villancicos –con su estrivillico– and matachines. The execution of a ballroom dance is even suggested in Afuela afuela:

“Tocamo la campaniya

y oldenamo Plussission,

cantando Kirieleyson

y responde la Capiya

tocando la bandurria,

danzando floreta,64

al son, campanela65 y quatro pe

le le le, ay Kirie,

ay Kirie Kirieleyson”.66

A final aspect that I would like to mention is the presence of local elements in the negrillas reviewed in this work. The internal structure of the musical works maintains the European format; thus it is impossible to maintain that the villancico was flexible enough to promote an “adaptation” to the conditions of each place. It is possible that hybridization processes may have manifested during live performances, although we cannot know for sure. In some examples of villancicos there are references to the gastronomy of the area, although it is not necessarily a diet of African origin. In stanza 3 of El negro maytinero we find:

“A sus sobrinos y nietos

combida que oygan pasar,

de sus Maytines el guiso,

de solomos en Pipiam”.

The sirloin in Pipiam –pepián– is meat in a sauce made from pumpkin seeds, sesame seeds and other roasted spices; to this day it is part of Guatemalan cuisine. Also, in the negrilla Ah, siolos molenos allusion is made to local food, for instance, when black men and women present Child Jesus with an offering of pumpkin syrup –“calambaza te aRope”–, rosquilla [a type of donut] and Oaxacan chocolatiya. On this matter, it would be necessary to further investigate in greater depth the scope of cultural transfer –multidirectional– during the period of Spanish colonization,67 however, that exceeds the limits of the present work.

Conclusions

As noted, ethnicity is constructed in villancicos de negros from an external perspective that reproduces narratives of difference as a real and immutable phenomenon. Despite the multidirectional nature of the processes of cultural transfer, the “black man” is not constructed as a historical subject, capable of defining its identity in its own terms, but pertains to a petrified and immutable category whose distinctive feature is –in addition to skin color– joy, devotion and innocence, in a permanent state of minority of age.

As for music, it could be observed that the chapel masters in Hispanic America continued the tradition of using specific compositional procedures to refer to the musical practices of African slaves: dialogue between a soloist and the choir –of “blacks”–, use of multiple percussion instruments, onomatopoeias, dances, lively rhythm, etc. The effect of this was the proliferation of musical works where the figure of black people is schematized.

Negrillas also reveal the social tensions that were present during colonial order, thus negrillas sometimes acquire a nuance of denouncement. The threatening figure of the quarrelsome black man is accompanied by vindictive speeches that contain expressions against whites. The lament for the social condition of Afro- descendants –or their blackness– reveals that ethnicity stands as a political and symbolic struggle for a place in the social landscape, although some sort of relief artifacts are posed, the truth is that conflicts are always neutralized by the presence of Child Jesus, devotion, humor and artistic practices –music, dance, theater– as facilitators of social reconciliation. It is dealt here with artifacts that generate spaces to liberate subaltern voices beyond the different levels around which ethnicity is constructed.

Based on the herein presented, I argue that villancicos de negros fulfilled a political function as the very action of incorporating Afro-descendants into the public life and exhibiting their difference is part of the institutional strategies to build ethnic boundaries that prevail over conflicts of class. Despite all, these pieces created the illusion of a united community around the universalizing values of Western culture. Innocent jubilation celebrates the ephemeral time in which subalternity is transformed into spectacle while power structures are strengthened and eternalized.

* Chilean. Postgraduate in Piano Performance Interpretation from the Staatliche Hochschule für Musik Freiburg, Germany; Master in Latin American Literature and Doctor in Studies of Society and Culture, University of Costa Rica (UCR), Costa Rica. Professor and researcher of the School of Music of the Universidad Nacional (UNA), Costa Rica. Email: deborah.singer.gonzalez@una.ac.cr

1 Frantz Fanon, Piel negra, máscaras blancas (Madrid, Spain: Ediciones Akal, 2009), 46. In Spanish.

2 This article was prepared thanks to the support of the Research Directorate of the Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica, which allowed me to visit the Archdiocesan Historical Archive “Francisco de Paula García Peláez” of Guatemala. My most sincere recognition to the staff working in the Archive and to the Guatemalan musicologist Omar Morales Abril. Some aspects of this topic were presented at the IV Congreso Centroamericano de Estudios Culturales, held in San José, Costa Rica, from July 17 to 19, 2013.

3 For more information regarding the maestros de capilla of Santiago of Guatemala, see: Omar Morales Abril, “Villancicos de remedo en la Nueva España”, in: Humor, pericia y devoción en la Nueva España, (ed.) Aurelio Tello (Oaxaca, Mexico: CIESAS, 2013), 11-38. In Spanish; Robert Snow, A New World Collection of Polyphony for Holy Week and the Salve Service (Guatemala City, Cathedral Archive, Music MS 4: The University of Chicago Press, 1996), 1-78; Dieter Lehnhoff, “Letra y música en los villancicos de maitines de Rafael Antonio Castellanos”, Cultura de Guatemala (Guatemala) Segunda Época, año XXIV, vol. 3 (September-December, 2003): 41-66. In Spanish; Dieter Lehnhoff, Creación musical en Guatemala (Guatemala City, Guatemala: Editorial Galería Guatemala, 2005), 69-85. In Spanish; Alfred Lemmon, “Las obras musicales de dos compositores guatemaltecos del siglo XVIII: Rafael Antonio Castellanos and Manuel José de Quiróz”, Mesoamérica (Guatemala) 5, n. 8 (1984): 389-401, available in: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4009137 In Spanish.

4 See: Robert Stevenson. “The Afro-American Musical Legacy to 1800”, The Musical Quarterly (EE. UU.) 54, n. 4 (October, 1968), 475-502, in: https://www.jstor.org/stable/i229642; Samuel Claro, Antología de la música colonial en América del Sur (Santiago, Chile: Ediciones de la Universidad de Chile, 1974). In Spanish.; Ángel M. Aguirre, “Elementos afronegroides en dos poemas de Luis de Góngora y Argote y en cinco villancicos de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz”, Atti del Convegno di Roma (Associazione ispanisti italiani), vol. 1 (1996), 295-311, in: https://cvc.cervantes.es/Literatura/aispi/pdf/07/07_293.pdf In Spanish.; Natalie Vodovozova, A Contribution to the History of the Villancico de Negros (Thesis, Master of Arts, The University of British Columbia, 1996); Glenn Swiadon, “Fiesta y parodia en los villancicos de negro del siglo XVII”, Anuario de Letras: Lingüística y Filología (Mexico) 42 (2011): 285-304, available in: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2272692 In Spanish.

5 The text of this Christmas villancico is also found in Joseph Pérez de Montoro, Obras Posthumas Lyricas Sagradas (Madrid, Spain: Oficina de Antonio Marin, 1736), 392-394. It is part of the Villancicos de Navidad that were sung in the cathedral of Cádiz in the Christmas of 1694.

6 Sebastián Durón was organist and maestro de capilla of the cathedrals of Seville, Cuenca, Burgo de Osma and Palencia –Spain–. In 1691 he was appointed master of the Royal Chapel of the King in Madrid. He lost his job in 1706 because of his explicit support for Archduke Charles of Austria against the Bourbon candidate and future King Felipe V.

7 On the cover of the manuscript it is written: “Fue a Nunualco a Manuel Dávila”. According to information provided by musicologist Omar Morales Abril, at AHAG there are at least five works that Castellanos sent to Manuel Dávila, a resident of Santiago Nonualco, El Salvador. It should be noted that in the AHAG there is another version of this villancico with the title Ah, señola plima mia, attributed to the maestro de capilla Nicolás Márquez Tamariz -Catalog n. º S 938-.

8 The text of this villancico is similar to one published by Joseph Pérez de Montoro, Obras Posthumas…, 284-287. It was sung in the cathedral of Cádiz on Christmas 1689.

9 It would be interesting to trace the text of this villancico as found in other Latin American cathedrals.

10 The change is attributed to Fray Hernando de Talavera, archbishop of Granada and former confessor of Queen Isabel The Catholic. See: Aurelio Tello, “Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz y los maestros de capilla catedralicios o de los ecos concertados y las acordes músicas con que sus villancicos fueron puestos en métrica armonía”, Pauta (Mexico) 16, n. 57-58 (January-June, 1996), 15. In Spanish.

11 The inclusion was not without controversy. Until the end of the 15th century, villancicos were opposed by many religious men because, as they pointed out, it directed more towards enjoyment than to spiritual recollection. This is what a canon of that time expressed in the cathedral of Granada: “It is not possible to tolerate… the praises of God are sung in such an irreverent and indecorous way… On Christmas Eve they introduce into the villancicos so many extravagant and indecent thoughts, and they deal with the highest matters in the lowest and most crude style, full of buffoonery so characteristic of the infamous plebe… bad profane couplets introduce and maintain the bad taste and irreverence”. See: German Tejerizo Robles, Villancicos barrocos en la Capilla Real de Granada (Seville, Spain: Editoriales Andaluzas Unidas S. A., 1989), 82. In Spanish.

12 Mabel Moraña, “Poder, raza y lengua: la construcción étnica del Otro en los villancicos de sor Juana”, in: Viaje al silencio. Exploraciones del discurso barroco (Mexico, D.F.: UNAM, 1998), in: http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra-visor/viaje-al-silencio-exploraciones-del-discurso-barroco--0/html/e5b96feb-bf21-4bd2-be1c-9389af0cb0ba_55.html In Spanish.

13 See: Carter Bentley, “Ethnicity and Practice”, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 29, n. 1 (January, 1987), 24-55, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S001041750001433X; Joane Nagel, “Constructing Ethnicity: Creating and Recreating Ethnic Identity and Culture”, Social Problems (England) 41, n. 1 (February, 1994), 152-176, DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/3096847; Eduardo Bonilla Silva, “Rethinking Racism: Toward a Structural Interpretation”, American Sociological Review (United States) 62, n. 3 (January, 1997), 465-480, DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/2657316; Hal B. Levine, “Reconstructing Ethnicity”, Journal of the Anthropological Institute (England) 5, n. 2 (January, 1999), 165-180, DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/2660691; Simon Dein, “Race, Culture and Ethnicity in Minority Research: A Critical Discussion”, Journal of Cultural Diversity (United States) 13, n. 2 (2006), 68-75; Andreas Wimmer, “The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: A Multilevel Process Theory”, American Journal of Sociology (United States) 113, n. 4 (January, 2008), 970-1022, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1086/522803; Rogers Brubaker, “Ethnicity, Race and Nationalism”, Annual Review of Sociology (United States) 35 (2009), 21-42, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115916; Tomás R. Jiménez, “Affiliative Ethnic Identity: A More Elastic Link Between Ethnic Ancestry and Culture”, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 33, n. 10 (April, 2010), 1756-1775, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01419871003678551; Emily M. Stovel, “Concepts of Ethnicity and Culture in Andean Archaelology”, Latin American Antiquity (England) 24, n. 1 (March, 2013), 3-20, DOI: https://doi.org/10.7183/1045-6635.24.1.3; Federico Navarrete Linares, Hacia otra historia de América. Nuevas miradas sobre el cambio cultural y las relaciones interétnicas (Mexico, D.F.: Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, UNAM, 2015), available in: http://www.historicas.unam.mx/publicaciones/publicadigital/libros/otrahistoria/hoha003_cambio.pdf In Spanish.

14 Nagel, “Constructing Ethnicity…”, 154.

15 Dein, “Race, Culture and Ethnicity…”, 72.

16 Wimmer, “The Making and Unmaking…”, 974.

17 This theoretical approach is developed by Bonilla Silva en “Rethinking Racism…”, 469.

18 Ibíd., 474.

19 Galen Bodenhausen and Jennifer A. Richeson, “Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination”, in: Advanced Social Psychology, (eds.) R. F. Baumeister and E. J. Finkel (Oxford, Union Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2010), 341-383.

20 Ibíd., 345.

21 Diane M. Mackie and David L. Hamilton, Affect, Cognition and Stereotyping. Interactive Processes in Group Perception (San Diego, United States: Academic Press, INC, 1993), 379.

22 Homi Bhabha, El lugar de la cultura (Buenos Aires, Argentina: Ediciones Manantial, 2002), 91. In Spanish.

23 Rogers Brubaker, “Etnicidad sin grupos”, in: Las máscaras del poder. Textos para pensar el Estado, la etnicidad y el nacionalismo, (ed.) Pablo Sandoval (Lima, Perú: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 2017), 425-463. In Spanish.

24 Ibíd., 433.

25 Pierre Bourdieu, Razones prácticas. Sobre la teoría de la acción (Barcelona, Spain: Editorial Anagrama, 1997), 48. In Spanish.

26 See: Robin Law, “La costa de los esclavos en África Occidental”, in: Rutas de la esclavitud en África y América Latina, (comp.) Rina Cáceres (San José, Costa Rica: EUCR, 2001), 29-43. In Spanish; Elisée Soumonni, “Ouidah dentro de la red del comercio transatlántico de esclavos”, in: Rutas de la esclavitud en África y América Latina, (comp.) Rina Cáceres (San José, Costa Rica: EUCR, 2001), 21-28. In Spanish.

27 I point out the fact that it was not a tonadilla from Guinea, but from Angola that was sung to the Child Jesus –el Niño–: “con toniya de Angola le ploculamo reposo”.

28 Marcella Trambaiolli, “Apuntes sobre el guineo o baile de negros: tipología y funciones dramáticas”, Memoria de la palabra. Actas del VI Congreso de la Asociación Internacional Siglo de Oro (2002), 1773-1783, in: https://cvc.cervantes.es/Literatura/aiso/pdf/06/aiso_6_2_072.pdf In Spanish.

29 See: Dein, “Race, Culture and Ethnicity…”, 72.

30 Francisco de Quevedo, Obras de Francisco Quevedo Villegas (Madrid, Spain: Joachim Ibarra Impresor, 1772), 230. In Spanish.

31 See: Aguirre, “Elementos afronegroides…”, 297-298. In Spanish; Vodovozova, A Contribution to the History…, 109-114.

32 John Lipski, “Literary ‘Africanized’ Spanish as a Research Tool: Dating Consonant Reduction”, Romance Philology (United States) 49, n. 2 (November, 1995), 130- 167, available in: http://php.scripts.psu.edu/faculty/j/m/jml34/afrodate.pdf

33 Ibíd., 144.

34 See: Jorge E. Porras, “Mexican Bozal Spanish in Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz’s Villancicos: A Linguistic and Sociolinguistic Account”, The Journal of Pan African Studies (United States) 6, n. 1 (July, 2013), 157-170.

35 Levine, “Reconstructing Ethnicity”, 169.

36 Jitanjáfora is a Spanish word describing the act of creating a linguistic statement constituted by words or expressions that are mostly invented and have no meaning in themselves. The term was first coined by Cuban poet Mariano Brull.

37 In Guatemalan indigenous villages called “fiscal” to the local maestro de capilla. He was the priest’s officer and could read and write. Among other things, he was responsible for Music and musicians at Mass.

38 This type character is also present in Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz’s villancios de negros. See: Alfonso Méndez Plancarte, Obras completas de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. II villancicos y letras sacras (México, D.F.: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1952). In Spanish.

39 Wimmer, “The Making and Unmaking…”, 994.

40 See: Juan Pablo Peña Vicenteño, “Relaciones entre africanos e indígenas en Chiapas y Guatemala”, Estudios de Cultura Maya (Mexico) 34 (January, 2009), 167-180, en: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0185-25742009000200006 In Spanish.

41 David Jickling, “The Vecinos of Santiago de Guatemala in 1604”, in: Estudios del Reino de Guatemala, (ed.) Duncan Kinkead (Seville, Spain: Escuela de Estudios Hispanoamericanos de Sevilla, 1985), 90. In Spanish.

42 See: Vodovozova, A Contribution to the History…, 29.

43 This file was found in 1972 by Cristopher Lutz in the Archivo General de Indias, Seville. See: Karen Darkin and Christopher H. Lutz, Nuestro pesar, nuestra aflicción. Tunetuniliniz, tucucuca. Memorias en lengua náhuatl enviadas a Felipe II por indígenas del Valle de Guatemala hacia 1572 (Mexico, D.F.: UNAM; Centro de Investigaciones Regionales de Mesoamérica, 1996), in: http://www.historicas.unam.mx/publicaciones/publicadigital/libros/nuestropesar/npesar.html In Spanish.

44 Lutz, Ibíd., 7.

45 Lutz, Ibíd., 17.

46 Pedro Cortés and Larraz, Descripción geográfico-moral de la Diócesis de Goathemala, Tomos I y II (Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional, 1958). In Spanish.

47 See: Severo Martínez Peláez, Motines de indios. La violencia colonial en Centroamérica y Chiapas (Guatemala City, Guatemala: F&G Editores, 2011), 63. In Spanish.

48 Magnus Mörner, La Corona Española y los foráneos en los pueblos de indios de América (Madrid, España: Ediciones de Cultura Hispánica, 1999), 127. In Spanish.

49 See: Catherine Komisaruk. “Hacerse libre, hacerse ladino: Emancipación de esclavos y mestizaje en la Guatemala colonial”, in: La negritud en Centroamérica, (eds.) Lowell Gudmunson and Justin Wolfe (San José, Costa Rica: EUNED, 2012), 204-205. In Spanish.

50 These are ordinances or laws pertaining to Spain’s colonial empire.

51 Mauricio Valiente, “El tratamiento de los no-españoles en las ordenanzas municipales indianas”, Estudios de Historia Social y Económica de América (Spain) 13 (1996), 47-58, in: http://hdl.handle.net/10017/5921 In Spanish; Carmen Bernand, “Negros esclavos y libres en las sociedades hispanoamericanas” (2000), in: http://www.larramendi.es/i18n/catalogo_imagenes/grupo.cmd?path In Spanish; Beatriz Palomo de Lewin, “Perfil de la población africana en el Reino de Guatemala”, in: Rutas de la esclavitud en África y Centroamérica, (comp.) Rina Cáceres (San José, Costa Rica: EUCR, 2001), 195-209. In Spanish; Aníbal Chajón Flores, El motín del Barrio San Jerónimo, en la ciudad de Santiago de Guatemala (1697-1701) (Thesis, Departament of History, Universidad Francisco Marroquín, Guatemala, 2000). In Spanish.

52 Thomas Gage, Los viajes de Thomas Gage en la Nueva España, Tercera Parte, Capítulo II (Guatemala City, Guatemala: Biblioteca de Cultura Popular, 1950), 23. In Spanish.

53 Pedro Cortés y Larraz, 294-295.

54 Ibíd., 192.

55 Ibíd., 193.

56 José Antonio Fernández points out that his task was to defend the colonies, especially once the mandatory military service provided by the Spanish encomenderos disappeared. See: “Población afroamericana libre en la Centroamérica colonial”, in: Rutas de la esclavitud en África y América Latina, (comp.) Rina Cáceres (San José, Costa Rica: EUCR, 2001), 323-340. In Spanish.

57 Salvador Montoya, 95.

58 According to the Dictionary of Authorities, Matachines was a dance in which four, six or eight people intervened in a cheerful tinkle making grimaces while beating each other with stick swords and air-filled cow bladders. The matachín wore a colorful costume adjusted to the body.

59 I thank Professor José Andrés Saborío for his help in this transcript.

60 Stevenson, “The Afro-American…”, 496-497; Dieter Lehnhoff, “Letra y música…”, 57- 58. In Spanish.

61 Transposition clefs were used in works of very high tessitura and indicated that the soloist should sing a perfect fourth below the given note; these were: second line treble clef for the Tiple, second line alto clef for the Alto, third line alto clef for the Tenor and fourth line alto clef –or third line bass clef– for the Bass.

62 Natural keys are: first line alto clef for the Tiple, third line alto clef for the Alto, fourth line alto clef for the Tenor, fourth line bass clef for the Bass.

63 Adufe is defined in the Diccionario de Autoridades as a certain genre of low and square drum similar to the tambourine. It is of Arabic origin and usually used by women to dance. See: Diccionario de Autoridades (Real Academia Española: 1726-1739), en: http://web.frl.es/DA.html

64 In the Diccionario de Autoridades it is described as the movement of both feet in the form of a flower.

65 Flip/turn made with a raised leg. Diccionario de Autoridades.

66 Sometimes the execution required the use of costumes, as seen in the grotesque parade of characters in Negliya que quele: “Jorgiyo de Angola vestido de Anguila, delante de Reye, baylando camina […] Antona de Congo, de mico veztira/ sobre un gran cameya, va haciendo baynica […] Flasico volteando como arliquiniya, en vez de maroma piza una sardina”.

67 See: Peña Vicenteño. In Spanish.