N.º 89 • Enero - Junio 2024

ISSN: 1012-9790 • e-ISSN: 2215-4744

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15359/rh.89.3

Licencia: CC BY NC SA 4.0

sección américa latina

Evolution of Coffee Policies in Mexico. XIX-XXI Centuries

Evolución de las Políticas Públicas de Café en México. Siglos XIX y XXI

Evolução da política pública do café no México. Séculos XIX e XXI

Claudia Oviedo-Rodríguez*

Abstract:

This paper characterizes the evolution of Mexican coffee policies, addressing how the state’s interest and its mechanisms for supporting coffee production have changed significantly over time. Three major phases of coffee policies were identified. First, during the late XIX and early XX centuries, the state was focused on expanding the number of hectares for coffee and facilitating land acquisition by large-scale farmers. Second, from 1958 to 1989, the state was interested in expanding coffee plantations and increasing productivity with higher-yield varieties and fertilizer. The state played a strong regulatory role in overseeing coffee prices and collecting farmers’ harvests; during this phase, small-scale farmers were the main target of support. Third, from 1989 to 2018, the state continued to promote increased productivity, but it also began to focus on improving quality. While small-scale farmers continued to be the principal target of support, the state significantly reduced its intervention in the coffee sector and primarily aided small-scale farmers through programs supplying plants and fertilizer.

Keywords: coffee policies; small-scale farmers; farmer organizations; industry; Mexico; history.

Resumen:

Este artículo estudia la evolución de las políticas de café en México, abordando cómo los intereses del estado y sus mecanismos de apoyo al sector han cambiado a lo largo de la historia. Se identificaron tres fases: 1) de finales del siglo XIX a inicios del XX, el estado se centró en ampliar el número de hectáreas para cultivo de café y en ofrecer facilidades de adquisición de tierras a agricultores de gran escala; 2) de 1958 a 1989, el estado se interesó en expandir las plantaciones de café, pero también en aumentar la productividad con variedades de mayor rendimiento. El estado desempeñó un fuerte papel regulador, estableciendo precios de café y recolectando las cosechas de los agricultores; durante esta etapa los pequeños agricultores fueron la prioridad de política pública; 3) de 1989 a 2018, el estado continuó impulsando el aumento de la productividad, pero también comenzó a enfocarse en mejorar la calidad. Si bien los pequeños agricultores continuaron siendo el principal objetivo del apoyo, el estado redujo significativamente su intervención en el sector y apoyó a los pequeños agricultores principalmente a través de programas que proporcionan plantas y fertilizantes.

Palabras claves: políticas de café; pequeños agricultores; organizaciones de agricultores; la industria; historia; México.

Resumo:

Este artigo estuda a evolução das políticas cafeeiras no México, abordando como os interesses do Estado e seus mecanismos de apoio ao setor mudaram ao longo da história. Foram identificadas três fases: 1) do final do século XIX ao início do século XX, o estado se concentrou na expansão do número de hectares para o cultivo do café e na oferta de facilidades de aquisição de terras aos grandes agricultores; 2) De 1958 a 1989, o estado teve interesse em expandir as plantações de café, mas também em aumentar a produtividade com variedades de maior rendimento. O Estado desempenhou um forte papel regulador, fixando os preços do café e recolhendo as colheitas dos agricultores; Nesta fase, os pequenos agricultores foram a prioridade das políticas públicas; 3) De 1989 a 2018, o estado continuou a pressionar pelo crescimento da produtividade, mas também começou a concentrar-se na melhoria da qualidade. Embora os pequenos agricultores continuassem a ser o principal alvo do apoio, o Estado reduziu significativamente a sua intervenção no sector e apoiou os pequenos agricultores principalmente através de programas que fornecem plantas e fertilizantes.

Palavras-chave: políticas cafeeiras; pequenos agricultores; organizações de agricultores; Indústria; história; México.

Policies focused on coffee production have a long history in Mexico. Ever since this crop was introduced to the country, coffee has been considered a significant source of income. However, state measures to support the sector have radically changed over time. While during the late XIX and early XX centuries, the state promoted coffee production by facilitating foreign large-scale farmers in acquiring land,1 2 during the second half of the XX century, the state-run Instituto Mexicano del Café (Mexican Coffee Institute [INMECAFE]) supported the sector by purchasing and processing the harvest of small-scale farmers.3 Although INMECAFE was dismantled in 1989, the state continued to support small-scale farmers, mainly by providing them with plants and fertilizer through farmer organizations.4

This paper characterizes the evolution of coffee policies. It addresses how the relationships between the state and large- and small-scale farmers underwent multiple transitions from the introduction of coffee in Mexico until the end of the Enrique Peña Nieto administration (2012–2018). While this analysis has a national scope, it particularly addresses the Soconusco region of Chiapas during the late XIX and early XX centuries, focusing on the role of large coffee-producing estates in this region. Information sources used for this research include scholarly articles that discuss the history of coffee and the state policies that have been implemented. Additionally, government documents related to state measures to promote the development of the coffee sector have been analyzed; they include the Mexican Constitution, national development plans, regulations, amendments to laws, and deeds concerning the creation of public institutes and programs.

This paper is structured as follows. The following section focuses on laws introduced by President Porfirio Díaz—who governed from 1876 to 1880 and 1884 to 1911—to increase coffee production, analyzing how foreign investors played a significant role in increasing production while dispossessing local populations of their land and employing them under exploitative labor conditions. The third section illustrates how, after the Mexican Revolution, the state promulgated the 1917 Constitution to favor land distribution and regulate labor conditions. However, not until the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas in the 1930s were corresponding reforms gradually implemented. The fourth section focuses on the period during which the coffee sector was most highly regulated through INMECAFE and the implementation of the International Coffee Agreement (ICA). The fifth section explains why INMECAFE was dismantled, and the ICA terminated in the late 1980s; it also discusses the consequences of these changes for small farmers’ livelihoods. The sixth section characterizes state policies implemented since the termination of INMECAFE and the ICA. The final section discusses changes in coffee policies over time.

State Support for Large-Scale Coffee Production5

Coffee was introduced to Mexico through the port of Veracruz in 1740, from which it was spread to other states, including Chiapas, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Nayarit, Oaxaca, Puebla, and San Luis Potosi.6 Historical sources indicate that during the conquest, the Spanish Crown stimulated coffee production by exempting taxes on the importation of implements to be used for this purpose.

From 1823 to 1861, following Independence (1810–1821), taxes on coffee sales were eliminated. However, national coffee production during those decades was low —less than 600 tons—.7 Only during the presidency of Porfirio Díaz did Mexico undergo a coffee boom, with annual yields exceeding 28,000 tons.8

This drastic increase was initially triggered by an abrupt rise in international coffee prices from the 1870s to the 1890s. This was due to the decline in production by Brazil, which was one of the world’s leading coffee producers at that time.9 Moreover, President Díaz introduced a variety of measures to increase the number of coffee plantations. In 1883, the Díaz administration emitted the Decreto de Colonización y Compañías Deslindadoras (Decree of Colonization and Surveying Companies), by which surveyors divided and received a commission on sales of vacant land for agricultural production. Through this decree, Mexican and foreign farmers could purchase up to 2,500 hectares on credit or claim up to 100 hectares with no charge as long as they guaranteed they would cultivate it for at least 5 years. Furthermore, the decree exempted farmers from 10 years of military service, taxes on coffee exports and farm implements, and fees on land titles and resident permits.10 In addition, in 1894, Díaz passed the Ley Sobre Ocupación y Enajenación de Terrenos Baldíos (Law of Occupation and Alienation of Vacant Land), establishing that any citizen—not only private companies—could announce the existence of a vacant piece of land and request to purchase it; with this law, the upper limit of 2,500 hectares for land purchase was eliminated.11 Díaz’s policies also included road and railway construction and improvement, as well as the introduction of innovative agricultural techniques and machinery.12

During the Díaz administration, Matías Romero —who served as Mexico’s Minister of Finance and Ambassador to the United States) widely promoted Soconusco as one of Mexico’s principal coffee-producing regions. While Soconusco was geographically, politically, and economically isolated at the time, and its territory had been disputed with Guatemala,13 14 Romero considered this fertile area ideal for coffee cultivation.15 In order to stimulate coffee production and attract the interest of investors, in 1882, he signed the Tratado de Límites entre México y Guatemala (Border Treaty between Mexico and Guatemala) to define the boundary between the two nations, incorporating Soconusco into Mexico.16 In addition, Romero facilitated the establishment of surveying companies, including the Compañía Mexicana de Colonización de San Francisco (San Francisco Mexican Colonization Company) and the British enterprise Chiapas Land and Colonization.17 Romero also requested the renovation of the San Benito Port to export coffee to the United States and promoted the construction of a railway to connect Soconusco to the port of Veracruz to ship coffee for export to Europe.18 Finally, Romero promoted Mexican coffee production at international events and in Mexican magazines and newspaper articles.19

The multiple incentives provided by the Díaz administration for expanding coffee cultivation, as well as the high coffee prices at the time, led to a migration of Mexican and foreign investors to different regions of Mexico.20 Investors, principally from Germany, established many coffee plantations in Soconusco. These plantations included El Retiro, Argovia, Santa Fe Chinincé, and San Nicolás, owned by Adolf Giesemann; Las Maravillas, owned by Juan Lüttmann; Hamburgo, owned by Arthur Erich Edelmann; Germania, Hannover, and Prussia, owned by Guillermo Kahle; Rancho Alegre, owned by Adolfo Gramlich; and La Libertad, San Antonio, Chicharras, Covadonga, Badenia, and Colonia, owned by von Türckheim.21 22

Many of the farmers who established these estates were either employees or partners in coffee trading companies based in Hamburg, Bremen, or Lübeck and received loans from these companies and the Deutsche Bank as long as they promised to meet certain production quotas.23 24 Others arrived from Guatemala, where they owned coffee plantations, but due to the scarcity of land and laborers, they decided to migrate to Soconusco. Still others came from the Mexican ports of Mazatlán and Manzanillo, where some coffee trading companies operated.25

These farmers—locally known as finqueros—promoted a radical transformation of the region. In approximately 30 years, they expanded coffee production from the outskirts of the Tacana Volcano to the Huixtla River —see Figure 1).26 Small-scale coffee farms were transformed into plantations averaging 1,200 hectares, yielding 30 to 40 quintals27 per hectare.28

Along with finqueros’ new infrastructure and equipment, coffee began to be processed as parchment coffee under the wet method29 rather than being sold as unprocessed coffee.30 Soconusco coffee, previously sold only in local and national markets, began to be shipped to Europe through international trading companies.31 Additionally, German farmers who settled in the region also created an association of large-scale farmers to coordinate coffee production and trading: La Unión Cafetalera del Soconusco (Soconusco Coffee Union).32

Expansion of Coffee Plantations in Soconusco by Finqueros in the Late XIX Century

Note: Elaborated by Marian Vittek, researcher of the Applied Spatial Research division of Wageningen Environmental Research Institute.

By the early XX century, Soconusco had become one of Mexico’s principal coffee-producing regions, yielding 9,200 tons annually, or nearly 30% of all coffee produced in Mexico and 90% of that produced in Chiapas.33 However, the increase in production was accompanied by dispossession of land from indigenous and other peasant communities. This was a continuation of the dispossession that began with Spanish colonizers upon invading Mexico and continued with the Catholic Church upon Independence from Spain. The Decreto de Colonización y Compañías Deslindadoras and the Ley Sobre Ocupación y Enajenación de Terrenos Baldíos established during the Díaz administration contributed to perpetuating dispossession of land, now through surveying companies.34

Coffee production also expanded at the expense of deplorable working conditions through peonaje por deudas (debt peonage). This system of indentured servitude was introduced so that recruiters, known as enganchadores,35 brought indigenous laborers from the Altos de Chiapas (Highlands of Chiapas) to Soconusco estates.36 However, upon signing a contract that they barely understood, indigenous laborers were taken on a 6–8 day walking trip to Soconusco, and the laborers covered their own travel expenses. Once on the plantation, laborers had to pay for work equipment and were paid with tokens that could only be exchanged at the tienda de raya (company store),37 where prices of food, cleaning products, and clothes were twice those off the farm.38 The German plantation owners paid only Mex$0.4039 per day,40 and as most laborers had incurred large debts, they were forced to return the following season or even remain on the plantation for the rest of their lives.41

In addition to the debt trap fomented by plantation owners, laborers faced inhumane living and working conditions. Housing for single laborers consisted of a communal room for up to 60 people, and for families, a single 10-square-meter room; all rooms had dirty floors and sheet metal roofs. Laborers worked 12 or 13 hours a day and were given only tortillas and beans to eat. Those who did not obey orders were beaten and even sent to solitary confinement within the plantation or to the municipal jail.42 Due to difficult working conditions, laborers often got sick and even died. Those attempting to escape were usually caught; when they were not, their families became responsible for paying their debt.43 Furthermore, estate owners registered infants born on the plantation and even selected their names.44 While some owners acknowledged their cruel treatment, they justified their actions by stating that laborers do not like to work and claimed that if they offered better pay or treatment, they would work less.45 Public functionaries did little to modify these conditions, given the profits indentured servitude generated for the region. 46 47

The Mexican Revolution and President Cárdenas’ Land Distribution

The concentration of land and wealth by exploiting laborers provoked one of the most emblematic wars in the history of the nation: the Mexican Revolution. This war was initially fomented by the writings of Ricardo and Enrique Flores Magón, who severely criticized Díaz’s dictatorship in their newspaper Regeneración (Regeneration), and who, in 1905, established the opposition party Partido Liberal Mexicano (Mexican Liberal Party).48 The war officially began on 20 November 1910, when Francisco Madero organized an armed movement to demand the revocation of Díaz as President after fraudulent elections for his 7th term.49

Throughout the 7-year war, revolutionary leaders organized armed movements in different parts of the country. The most well-known were Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata. Pancho Villa led the army División del Norte (Northern Division), taking over large estates and confiscating the goods of wealthy farmers who benefited from the Díaz administration.50 Emiliano Zapata led the Ejército Libertador del Sur (Southern Liberation Army) and drew up the Plan de Ayala (Ayala Plan) to demand redistribution of estate land to communities that had been dispossessed.51

In 1917, after years of bloody confrontation, the Mexican Revolution ended with the promulgation of a new constitution containing two significant articles on agrarian reform. The first one was Article 27. It declared that the state had the right to regulate natural resources and distribute wealth, prioritizing public over private interest. This article also legislated the division of large estates, declaring null and void all land concessions that had deprived communities of land and demanding restitution to the original owners. The second was Article 123, which introduced radical changes to labor conditions. It established a minimum wage and an 8-hour workday while also prohibiting child labor and the token system. It also demanded that finqueros pay workers with cash and provide decent housing, health care, and disability coverage. Furthermore, it granted laborers the right to unionize and go on strike.52

In addition to these articles, as an outcome of the Mexican Revolution, the state of Chiapas introduced the Ley de Obreros (Workers’ Law), which made servitude illegal and forgave all laborers’ debts. This law also established weekly pay, prohibited raya stores, imposed jail and fines on anyone mistreating laborers, and demanded the establishment of schools on the estates.53

Despite these laws, their implementation was limited throughout the 1920s and part of the 1930s in Chiapas. With the support of the German chancellor, Heinrich von Eckardt, finqueros obtained permission to re-implement the debt peonage upon promising to pay a tax of Mex$0.25 for every 100 kilos to the Mexican state.54 Physical punishment was reduced during this period, and a few schools were opened. However, the raya stores continued to operate, and laborers worked more than 8 hours for less than minimum wage, without access to health care. Tiburcio Fernández Ruiz, who governed Chiapas from 1920 to 1924, also limited the revolutionary reforms by establishing that only those estates with over 8,000 hectares were susceptible to land distribution. Although some land was distributed during his term, it was of inferior quality.55

Continuing land concentration and oppression of laborers following the Revolution provoked the emergence of multiple socialist and communist parties and labor unions in Chiapas, including in the Soconusco region. Examples of these organizations were the Partido Socialista Chiapaneco (Chiapas Socialist Party), the Confederación Socialista de Trabajadores de Chiapas (Socialist Confederation of Workers of Chiapas), the Partido Socialista del Soconusco (Socialist Party of Soconusco), the Partido Comunista del Soconusco (Communist Party of Soconusco), and the Sindicato de Obreros y Campesinos del Soconusco (Union of Workers and Peasants of Soconusco).56 57

These parties and unions pressured German landowners and public functionaries to comply with the laws resulting from the Revolution. For instance, in 1922, with the support of the Partido Socialista Chiapaneco, 7,000 laborers of Soconusco estates organized a strike to demand an 8-hour workday, more schools on the estates, and an increase in the daily wage from Mex$1.00 to Mex$1.20.58 59 Members of these parties and sympathetic functionaries also established conciliation and arbitration offices in different regions of Chiapas and passed laws to establish collective labor contracts and increase wages. However, these achievements were accompanied by co-optation, persecution, and assassination of many social leaders, which contributed to weakening the movement.60

Not until the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas (1936 to 1940) did the objectives of the Revolution begin to be fulfilled to a significant extent. Recognizing that finqueros continued to concentrate land at the expense of laborers and that the 1917 Constitution did not consider estate laborers to be subject to land distribution, Cárdenas modified the Código Agrario (Agrarian Code), which regulated rural landholdings, to divide and distribute all estates exceeding 300 hectares, and simplified the process by which landless peasants could acquire land.61 To overcome what Cárdenas termed the latifundio primitivo (primitive latifundium), he promoted collective cultivation and assigned ejidos the responsibility of supplying food to the country and stimulating the internal market.62 63

To support the ejidos in accomplishing their role, Cárdenas granted the Departamento de Asuntos Agrarios y Colonización (Department of Agrarian and Colonization Affairs) power of regulating land acquisition in favor of ejidos. Additionally, he established the Departamento Agrario (Agrarian Department) to support ejido production. Then, he created the Banco Nacional de Crédito Ejidal (National Bank of Ejido Loans) to provide loans to ejido members for farm equipment and infrastructure.64 To accelerate state attention to the demands of farmers and farmworkers, Cárdenas encouraged their incorporation into the Confederación Nacional Campesina (National Peasant Confederation [CNC]) as well as into the governing party, the Partido Nacional Revolucionario (National Revolutionary Party),65 and promoted their right to strike and carry out other forms of protest.66 67

In contrast to previous administrations that distributed very little land in Chiapas,68 Cárdenas allocated ٤٤٨,١٥٠ hectares.69 He also established the Departamento de Protección Indígena (Department of Indigenous Protection) and the Agencia Gratuita de Colocaciones (Free Agency for Placement) to regulate contracts between estates and laborers. Additionally, he established the Comisión Demográfica Intersecretarial (Inter-agency Demographic Commission) so that estate laborers could prove their citizenship and thereby receive land upon distribution.70 During the Cárdenas administration, new unions were formed in Chiapas, including the Sindicato de Trabajadores Indígenas (Indigenous Workers’ Union) and the Sindicato Único de Trabajadores de la Industria del Café y Similares del Estado de Chiapas (Single Union of Workers of Coffee and Similar Industries of the State of Chiapas).71

Finqueros resisted these changes by offering money to laborers so they would cease their strikes, or by burning their houses if they refused to accept their bribes. They also threatened Guatemalan laborers with deportation, persecuted agrarian leaders who encouraged laborers to protest, and sold part of their land to their own family members to conceal the amount of land they held. Nonetheless, despite these actions, most estates were divided and redistributed during the Cárdenas administration. The few that survived this administration deteriorated significantly during the Second World War when the United States requested Mexico to confiscate German enterprises.72 73

Subsequently, the Cárdenas administration is widely remembered for providing land to many small farmers. However, many stumbling blocks for small farmers emerged during this period. Although large farms were distributed, finqueros retained their machinery and entered the coffee processing industry. Meanwhile, many intermediaries began to trade coffee locally and acquire much control over coffee prices.74 Furthermore, although the state assigned several government agencies the responsibility of fomenting ejido production, these agencies were quite inefficient and corrupt. Thus, small farmers relied on large-scale farmers and local intermediaries for some services that the state did not provide to a sufficient extent, such as loans.75 Additionally, the largest farmer organization promoted by Cárdenas—the CNC—became corrupt and functionaries and local leaders ended up operating according to clientelism.76

State Regulation of the Coffee Industry

Following the Cárdenas administration, the Mexican state began to intervene in the regulation of different economic sectors. Regarding the coffee sector, this regulatory role was implemented in stages. First, in 1949, as an outcome of high coffee prices on an international level, President Miguel Alemán (1946–1952) established the Comisión Nacional del Café (National Coffee Commission) to oversee the restoration and maintenance of coffee plantations, research on cultivation and processing methods, control of plant diseases, training of farmers, provision of loans, and issuance of export permits.77 It also intervened in coffee processing and trading by creating the company Beneficios Mexicanos del Café (Mexican Coffee Processing), although such intervention was minimal.78 During this period, large-scale farmers and processing and exporting companies continued to be the main beneficiaries of state agricultural support.79

In 1958, the state’s functions concerning the coffee industry changed due to the replacement of the Comisión Nacional del Café by INMECAFE. Similar to the Comisión, INMECAFE was responsible for conducting research and training farmers to increase coffee production. It also took on the tasks of collecting coffee, regulating prices on a national level, and assuring that Mexico fulfilled the national coffee quota set by the ICA80 81—the principal coffee regulatory mechanism through which coffee-producing and consuming countries maintained coffee prices within the range of US$1.20 to US$1.40 per pound82 by implementing production quotas.83 84 While the Comisión Nacional del Café prioritized large farmers, INMECAFE began to favor ejido members who had acquired land through Cárdenas’ land distribution.85

In 1973, under the presidency of Luis Echeverría (1970–1976), in the context of another wave of high coffee prices and high petroleum revenues,86 INMECAFE initiated a campaign to maximize coffee production and collection. During this period, the state organized small farmers into the Unidades Económicas de Producción y Comercialización (Economic Units of Production and Marketing [UEPCs]) to provide them with plants, technical assistance, advanced payment, and low-interest loans in exchange for promising to deliver their coffee to INMECAFE.87 With the grouping of small-scale farmers into the UEPCs, the state also aimed to foment participation of farmer organizations in other functions of the coffee value chain in addition to production.88 Furthermore, Echeverría passed the Ley Federal de Reforma Agraria (Federal Agrarian Reform Law) in 1971 and the Ley General de Crédito Rural (General Law of Rural Loans) in 1976 to foster the creation of umbrella organizations consisting of two or more farmer organizations to market coffee and manage financial services.89 90

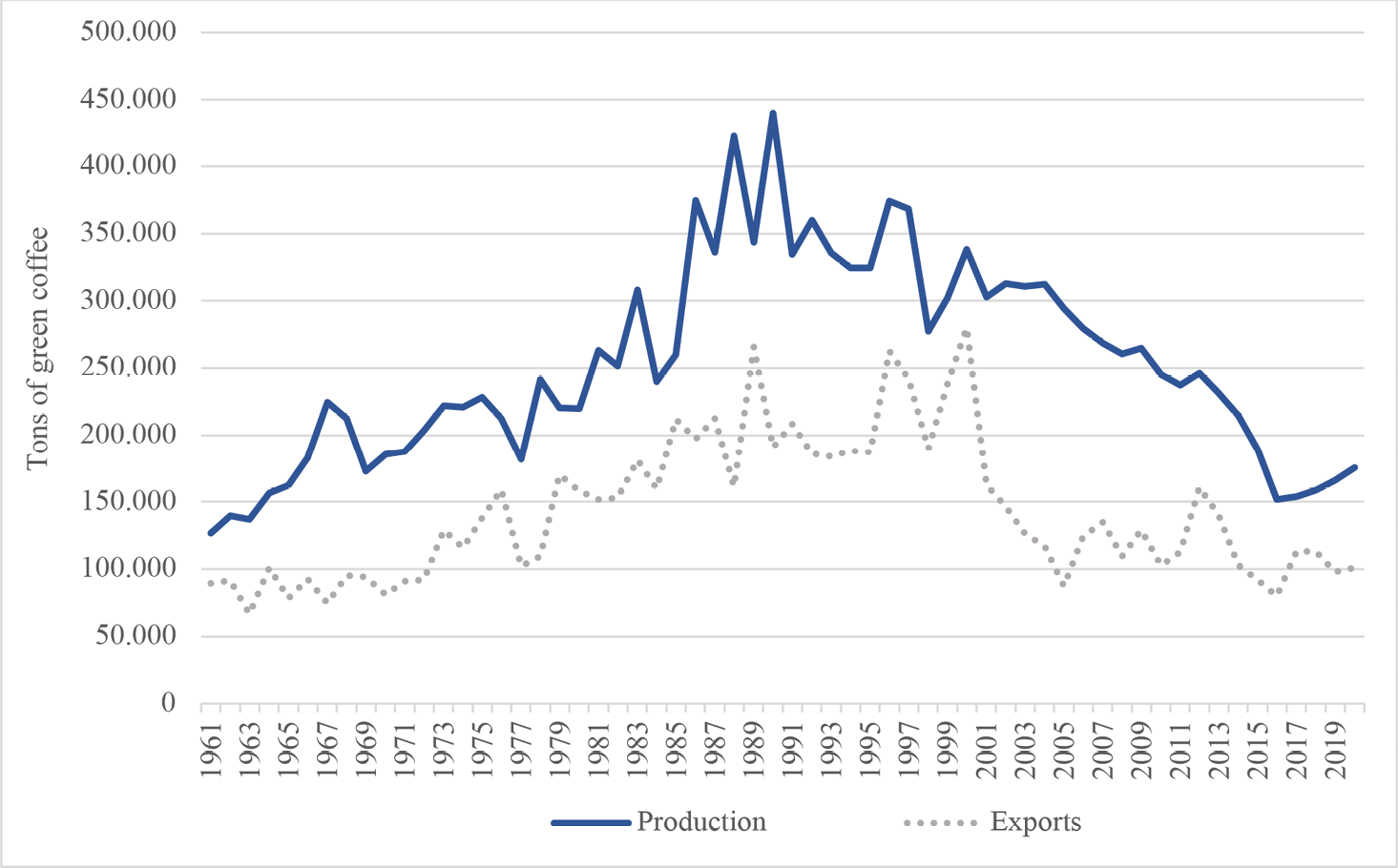

During the operation of INMECAFE, coffee production and exports reached some of their highest levels of the XX and XXI centuries (See Figure 2).91 92 Many refer to this period as the golden age of Mexican coffee, not only as a result of high yields but also because INMECAFE’s collection services allowed farmers to bypass local intermediaries. However, this institute was also highly criticized for providing inputs and loans after they were needed, using deceitful practices to weigh farmers’ coffee, paying low coffee prices, promoting intensive cultivation with high levels of fertilizer, reducing shade, increasing planting density, using varieties that produce high volumes but of lower quality, and exporting coffee under a homogenous category regardless of variation in quality.93 Furthermore, critics point out that although INMECAFE established a large number of UEPCs (3,396 with a total of 160,000 farmers),94 these groups achieved very little autonomy and gained limited knowledge about coffee trading. It is also argued that the CNC and the prevailing Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Institutional Revolutionary Party [PRI]) co-opted some of the umbrella organizations created during this period.95

Coffee Production and Exports, 1961–2018

Note: Elaborated with data from FAOSTAT.

Due to the inefficiency of INMECAFE and its clientelist practices, many coffee farmer organizations founded in the 1970s and 1980s decided to seek alternatives to INMECAFE, namely the organic market. While these organizations did not sever relations with the state, they prioritized what they called their political autonomy. These organizations include the following: in Chiapas, the Unión de Uniones Ejidales y Grupos Campesinos Solidarios de Chiapas (Union of Unions of Ejido and Peasant Solidarity Groups of Chiapas), the Unión de Ejidos y Comunidades Cafeticultores Beneficio Majomut (Majomut Union of Ejidos and Coffee Communities Processer [Majomut]), and Indígenas de la Sierra Madre de Motozintla (Indigenous Peoples of the Sierra Madre of Motozintla [ISMAM]); in Veracruz, the Unión de Productores de Café de Veracruz (Union of Coffee Producers of Veracruz [UPCV]); in Oaxaca the Unión de Comunidades Indígenas de la Región del Istmo (Union of Indigenous Communities of the Isthmus Region [UCIRI]); and in Puebla Tosepan Titataniske (United, We Shall Overcome).96 97

The End of the ICA and INMECAFE

In July 1989, after a period of high-level regulation of the coffee sector internationally, the ICA was terminated as a result of a series of disagreements among coffee-producing and consuming countries regarding the governance of the agreements (1999).98 99 Its termination generated one of the severest crises of the coffee sector ever as liberalization of global reserves led to a decline in coffee prices from a longstanding average of US$1.10 per pound (January–June 1989) to US$0.70 per pound in October 1989.100 101 Since then, coffee prices have been set through speculation on the stock market.102

Furthermore, mere months after the ICA was terminated, the Mexican state began reducing its coffee sector intervention. In September 1989, the administration of Carlos Salinas de Gortari (1988–1994)—known to have been one of the most corrupt presidents in Mexican history—declared that INMECAFE faced major financial loss and claimed that coffee collection was expensive and inefficient. Under the premise of modernization fostered by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, the administration announced the end of the state’s role in coffee collection, processing, and trading.103 104 Moreover, in 1992, Salinas announced modification of Article 27 to end land distribution officially, and in 1993, signed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) to reduce tariffs and promote foreign investment.105 106

With the state’s withdrawal from coffee production and marketing, Salinas urged farmer organizations to take the lead in the agricultural sector by establishing what became known as the Concertation Agreements, through which organizations began to participate in the design and implementation of agricultural programs.107 He also established the Congreso Agrario Permanente (Permanent Agrarian Congress) as an interlocutor between farmer organizations with a variety of political affiliations on the one hand and the state on the other.108 109 Additionally, he formed the Consejo Mexicano del Café (Mexican Coffee Council) consisting of representatives of Mexico’s Ministry of Agriculture, small farmer organizations, the coffee processing industry, and exporters to formulate coffee policies based on consensus.110 Furthermore, to support small farmers in the face of low coffee prices resulting from the termination of the ICA, Salinas provided loans to farmers through the Programa Nacional de Solidaridad (National Program of Solidarity [PRONASOL]) and encouraged farmers to form Comités Locales de Solidaridad (Local Solidarity Committees) to foster mutual collaboration.111

Nevertheless, these compensatory measures were characterized by several problems. First, the Congreso Agrario Permanente ended up benefiting the CNC—the farmer organization aligned with the ruling PRI party.112 Second, decisions made within the Consejo Mexicano del Café principally favored a few companies that had come to monopolize coffee processing and trading since INMECAFE was dismantled.113 Third, funding provided by PRONASOL was insufficient for farmers to carry out agricultural projects, and the Comités Locales de Solidaridad rarely participated in higher functions of the value chain. Finally, the absence of the state in coffee collection and trading led local buyers to control the sector.114

Hence, in a context of very low coffee prices and palliative measures by the state, the regional coffee organizations that had operated since the 1970s and 1980s, such as Majomut and UCIRI, as well as more recent organizations such as the Coordinadora Estatal de Productores de Café de Oaxaca (State Coordinator of Coffee Producers of Oaxaca [CEPCO]), joined together to increase their participation in the organic market and pressure the state to support for small-scale farmers.

In 1989, these coffee organizations, along with other farmer organizations, established the Coordinadora Nacional de Organizaciones Cafetaleras (National Coordinator of Coffee Organizations [CNOC]), which became Mexico’s largest coffee farmer organization and the principal representative of small farmer organizations in public policy development.115 The CNOC also emerged as a key representative of small farmers’ resistance movements, as seen in the 2002 campaign El Campo No Aguanta Más (The Countryside Can Take No More) and the 2007 movement Sin Maíz no Hay País (Without Maize There Is No Country). Through these initiatives, numerous farmer organizations opposed policies established by NAFTA and demanded the re-formulation of trade agreements to guarantee food sovereignty and support production by small farmers.116

Coffee Policies During the Expansion of Neoliberalism

From the Salinas administration to Enrique Peña Nieto’s presidency, the Mexican state sustained support for small-scale coffee production, principally through programs providing plants, fertilizer, and technical assistance channeled through farmer organizations. Such programs included the 1998 Programa de Impulso a la Producción del Café (Program to Promote Coffee Production),117 the 2011 Programa Fomento Productivo del Café (Program for Promotion of Coffee Production),118 and the 2013 Programa PROCAFE e Impulso Productivo al Café (Program PROCAFE and Productive Fomentation of Coffee).119

In contrast to previous years when INMECAFE principally focused on increasing productivity due to greater competition among coffee-producing countries, these programs fostered the improvement of coffee quality by encouraging small farmers to replace old plants and process their coffee cherries into parchment coffee using the wet method.120 Additionally, since the passing of the 2001 Ley de Desarrollo Rural Sustentable (Sustainable Rural Development Law [LDRS]), coffee programs began to foster organic production.121 For instance, the Programa Fomento Productivo del Café provided a greater subsidy to organic farmers than to conventional farmers,122 and the PROCAFE e Impulso Productivo al Café covered 70% of the cost of organic coffee certification.123 124

Besides providing plants and fertilizer, since the ICA ended and INMECAFE was dismantled, the state implemented the Fondo de Estabilización del Café (Coffee Stabilization Fund) to compensate farmers with monetary payments when the price of coffee fell below US$0.70 per pound; meanwhile, farmers contributed to the fund when the price exceeded US$0.85 per pound. 125 126 127 In addition, the state launched several campaigns to support farmers in combatting coffee leaf rust—a fungus greatly affecting yields—and distributed introgressed varieties128 resistant to rust.129 130 During this period, the state also created the Padrón Nacional Cafetalero (National Coffee Producers’ Registry) to create a census of the beneficiaries of coffee programs.131

Aside from implementing these programs, in 2004, the Mexican state replaced the Consejo Mexicano del Café with the Sistema Producto Café (Coffee Product System) in order to formulate policies jointly among the state, farmer organizations, and the coffee processing industry.132 Later, in 2006, it established the Asociación Mexicana de la Cadena Productiva Café (Mexican Coffee Value Chain Association [AMECAFE]) to assist the Ministry of Agriculture in designing and implementing coffee policies, improving the quality of coffee, promoting consumption of coffee on a national and international level, and managing the low-price compensation funds.133 134

Despite the diversity of measures that the state implemented after INMECAFE was dismantled, its performance was highly criticized for clientelism promoted by farmer organizations and functionaries of the PRI and Partido Acción Nacional (National Action Party [PAN]).135 136 The state faced further criticism for several shortcomings in its coffee programs. Firstly, these programs provided were notably low. Secondly, farmers received poor-quality plants and fertilizer, often delivered too late in the planting season to make use of them. Thirdly, the state provided no marketing strategies or failed to implement them effectively. Fourthly, it failed to extend loans to farmers and provide technical assistance and supervision consistently. Finally, it addressed coffee rust inefficiently and introduced lower-quality resistant varieties.137 138 139

Furthermore, the state was criticized for a lack of coordination among the ministries involved in implementing agricultural programs. Additionally, AMECAFE was deficient in human resources and budget to adequately attend to small farmers’ demands; it also did not possess the authority to regulate the coffee sector as INMECAFE did.140 Likewise, despite the fact that the Sistema Producto Café was intended to formulate policies through consensus among all actors of the value chain, many farmer organizations have complained that the Consejo Nacional Agropecuario (National Agricultural Council) and Asociación Nacional de la Industria del Café (National Association of the Coffee Industry), which represent the coffee processing industry in the Sistema Producto Café, used their influence to counter the interests of small farmer organizations.141

Scholars and coffee farmer organizations have also lamented the state’s openness to allowing the coffee processing industry to operate in Mexico and its tolerance of low quality in the sector.142 143 Coffee farmer organizations were particularly concerned with Nestlé. Since 2010, it has operated its Nescafé Plan to expand robusta production—which coffee organizations consider lower quality than arabica—by providing plants and technical assistance to farmers of Veracruz and Soconusco.144 145 Moreover, coffee farmer organizations were concerned that the Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (National Institute of Forestry, Crop Agriculture, and Livestock Research [INIFAP]) supported Nestlé directing research on coffee breeding. Finally, farmer organizations were concerned the state also actively supported the growth of this company by fostering the expansion of a Nestlé factory in Toluca in 2013 and the establishment of the world’s largest instant coffee factory in Veracruz in 2019.146

This paper analyzed the evolution of coffee policies since the crop was introduced to Mexico, showing that while the state has continually promoted coffee production, its interests and measures of support to farmers have varied over time. Three major phases of coffee policies were identified. First, during the late XIX and early XX centuries, the state focused on expanding the number of hectares for coffee production and exporting coffee to North America and Europe. During this phase, the state mainly benefitted large-scale farmers by facilitating land acquisition and providing various types of incentives for them to establish coffee farms in Mexico. During this period, Soconusco played a significant role in increasing Mexican coffee production; however, this was achieved through dispossession of indigenous peoples’ land and deplorable labor conditions on coffee plantations.

The second phase occurred from 1958 to 1989 when INMECAFE was in operation. Similar to the previous phase, the Mexican state was interested in expanding coffee plantations but also in increasing productivity with higher-yield varieties and fertilizer. In contrast to the previous phase, when the state mainly supported the sector by facilitating land purchases, during this phase, it played a strong regulatory role by conducting agricultural research, training farmers, and collecting and processing coffee. In contrast to previous decades, small-scale farmers —particularly ejido members— were the principal target of support during this phase. While many scholars and farmer organizations observed that thanks to INMECAFE, small-scale farmers were able to avoid local intermediaries, they have highlighted that its operations were characterized by inefficiency and corruption.

The third phase lasted from 1989 to 2018, the final year analyzed. During this phase, the state continued to promote increased productivity but also began to focus on improving quality. While small-scale farmers continued to be the principal target of support, the state principally supported these farmers through programs providing plants and fertilizer via farmer organizations, having significantly reduced its intervention in the coffee sector by ceasing to regulate coffee production quotas and to purchase and process coffee. During this phase, the state implemented many programs to support small-scale coffee farmers. However, scholars and farmer organizations complained of inefficiency, including the ill-timed provision of inputs and failure to promote marketing strategies. Additionally, due to the state’s withdrawal, the coffee processing industry acquired more functions within the value chain, such as conducting research, organizing farmers, and collecting and processing coffee.

Furthermore, this paper demonstrated that Mexican coffee policies have been operating within the framework of three interconnected phenomena: 1) the dynamics of coffee trading on an international level, 2) global development paradigms, and 3) the functioning of the Mexican state concerning agricultural policy. Regarding the first, this paper has shown how the Mexican state aligned with the ICA to maintain coffee prices within a certain range. It illustrated that high coffee prices on a global level in the late XIX century triggered the Mexican state to foster coffee production and establish the Comisión Nacional del Café (the predecessor of INMECAFE) in the late 1940s. High coffee prices also motivated INMECAFE to increase its coffee collection capacities in the early 1970s. Moreover, this paper showed how, after the ICA ended in 1989, due to low coffee prices, the state implemented a variety of programs to support farmers in the context of low coffee prices.

Regarding global development paradigms, this paper showed how Mexican coffee was produced during the late XIX and the early XX centuries in an international context of liberalization in which producing countries sold coffee without any authority regulating prices and without any quota restrictions. However, during the second half of the XX century, Mexican policies were embedded in a highly regulated economy where coffee-producing countries agreed to production quotas and established an international regulatory authority (the ICO). Later, following the end of the ICA until the presidency of Enrique Peña Nieto, coffee was marketed within a neoliberal international context. Coffee-producing countries began cultivating without any production quotas, and the stock market began setting coffee prices.

Finally, the paper showed how Mexican coffee policies were influenced by factors that determined the Mexican agricultural policy as a whole. Such factors include: 1) iconic events, such as the Mexican Revolution and the Proclamation of the 1917 Constitution; 2) establishment of ejido production, along with promotion of farmer organizations; and 3) prevalence of clientelism and deficient implementation of policies. In other words, the functioning of Mexican coffee policies share characteristics with policies focused in other crops.

I would like to thank Kees Jansen and Sietze Vellema, Associate Professors from Wageningen University, for their guidance with this paper; three anonymous reviewers selected by the journal for their suggestions; and Ann Greenberg for editing the paper.

Avella Alaminos, Isabel. “Los cafetaleros alemanes en el Soconusco ante el Gobierno de Carranza (1915).” In Anuario 2000, 445–476. Tuxtla Gutiérrez: UNICACH, 2002.

Bartra Vergés, Armando, Rosario Cobo, and Lorena Paz Paredes. La hora del café. Dos siglos a muchas voces. Ciudad de México: CONABIO.

Baumann, Friederike. “Terratenientes, campesinos y la expansión de la agricultura capitalista en Chiapas, 1896–1916.” Mesoamérica, n. 5 (1983): 8–63. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4009438

Celis Callejas, Fernando. “Intercambio de favores.” Accessed June 10, 2022. https://www.jornada.com.mx/2008/09/12/plaga.html.

Celis Callejas, Fernando. La Jornada, “Las organizaciones de los cafetaleros”. November 14, 2009. https://www.jornada.com.mx/2009/11/14/cafetaleros.html

Celis Callejas, Fernando. La Jornada, “El TLCAN y la cafeticultura mexicana”. November 16, 2013. https://www.jornada.com.mx/2013/11/16/cam-cafe.html

Celis Callejas, Fernando. La Jornada, “La CNOC: Una organización cafetalera independiente”. August 15, 2015. https://www.jornada.com.mx/2015/08/15/cam-cnoc.html

Celis Callejas, Fernando. “Unión de Productores de Café de Veracruz. Del cambio de terreno al fortalecimiento de una organización democrática.” In Cafetaleros. La construcción de la autonomía. Cuadernos de desarrollo de base 3, 157–171. Ciudad de México: CNOC, 1991.

Chapoy Bonifaz, Dolores Beatriz. Planeación, programación y presupuestación. Ciudad de México: UNAM, 2003.

Facebook. CNOC Post. 2018. https://www.facebook.com/Ecochavarrillo/videos/517947245358753

Facebook. CNOC Post. 2019a. https://www.facebook.com/cnocafe/posts/960323497425312

Facebook. CNOC Post. 2019b. https://www.facebook.com/cnocafe/posts/1251080245016301

Facebook. CNOC Post. 2022a. https://www.facebook.com/632587553532243/posts/3603042169820085/?app=fb

Facebook. CNOC Post. 2022b. https://www.facebook.com/632587553532243/posts/3351038355020469/?app=fbl

Cruz Hernández, Isabel. El Financiero, “La Nestlé y la ausencia de estrategias gubernamentales en el café”. January 08, 2019. https://www.elfinanciero.com.mx/opinion/isabel-cruz/la-nestle-y-la-ausencia-de-estrategias-gubernamentales-en-el-cafe/

De Grammont, Hubert C., and Horacio Mackinlay. “Las organizaciones sociales y la transición política en el campo mexicano”. In: La construcción de la democracia en el campo latinoamericano, edited by Hubert C. de Grammont, 23–68. Buenos Aires, Argentina: CLACSO, 2006.

De Grammont, Hubert C., Horacio Mackinlay, and Richard Stoller. “Campesino and indigenous social organizations facing democratic transition in Mexico, 1938–2006.” Latin American Perspectives, n. 4 (2009): 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X09338588

Enciso, Angélica. La Jornada, “El Congreso Agrario Permanente: ¿10 años no es nada?”. April 28, 1999. https://www.jornada.com.mx/1999/05/25/cam-agrario.html

FAO. “Cultivos y productos de ganadería”. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.fao.org/faostat/es/#data/QCL

Folch, Albert, and Jordi Planas. “Cooperation, fair trade, and the development of organic coffee growing in Chiapas (1980–2015)”. Sustainability, n. 2 (2019): 2–22. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020357

García, Arturo. “Proceso de construcción del movimiento campesino en México: La experiencia de la CNOC”. In Cafetaleros. La construcción de la autonomía. Cuadernos de desarrollo de base 3, 9–16. Ciudad de México: CNOC, 1991.

García Aguilar, María del Carmen, Daniel Villafuerte Solís, and Salvador Meza Díaz. “Café y neoliberalismo. Los impactos de la política cafetalera en el Soconusco, Chiapas”. In Anuario 1992, 285–302. Tuxtla Gutiérrez: ICHC, 1993.

Gómez de Silva Cano, Jorge J. El derecho agrario mexicano y la Constitución de 1917. Ciudad de México: SEGOB/CULTURA/INEHRM/UNAM, 2016.

González Jácome, Alba. “Dealing with risk: Small-scale coffee production systems in Mexico.” Perspectivas Latinoamericanas, n. 1 (2004): 1–39. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/236154861.pdf

Guerrero Galván, Luis René. “A propósito del aniversario Porfiriano. Una aproximación acerca de las compañías deslindadoras en tiempos del Porfiriato”. Revista Latinoamericana de Derecho Social, n. 22 (2016): 257–268. https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/rlds/n22/1870-4670-rlds-22-00009.pdf

Hernández, Luis. “Café: Privatización y concertación social”. El Cotidiano, n. 38 (1990): 53–58. https://www.ceccam.org/node/349

Hernández, Luis. “Cafetaleros: Del adelgazamiento estatal a la guerra del mercado”. In Autonomía y nuevos sujetos sociales en el desarrollo rural, edited by Julio Moguel, Carlota Botey and Luis Hernández, 78–97. Ciudad de México: Siglo XXI/CEHAM, 1992a.

Hernández, Luis. “Las convulsiones rurales”. In Autonomía y nuevos sujetos sociales en el desarrollo rural, edited by Julio Moguel, Carlota Botey y Luis Hernández, 235–260. Ciudad de México: Siglo XXI/CEHAM, 1992b.

INEHRM. Lázaro Cárdenas: Modelo y legado. Vol. II. Ciudad de México, 2020.

Jurado Celis, Silvia, and Armando Bartra Vergés. “Cómo sobrevivir el mercado sin dejar de ser campesino. El caso de los pequeños productores de café en México”. Veredas: Revista del Pensamiento Sociológico Especial (2012): 181–191. https://veredasojs.xoc.uam.mx/index.php/veredas/article/view/511

Kuntz Ficker, Sandra. “El café”. In Las exportaciones mexicanas durante la primera globalización (1870–1929), 291–344. Ciudad de México: COLMEX, 2010

Lurtz, Casey Marina. From the grounds up. Building an export economy in southern Mexico. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2019.

Martínez Morales, Aurora Cristina. El proceso cafetalero mexicano. Ciudad de México: UNAM, 1996.

Martinez-Torres, Maria Elena. “Sustainable development, campesino organizations and technological change among small coffee producers in Chiapas, Mexico.” PhD dissertation. University of California. 2003. https://www.proquest.com/openview/e6f39aa3e295f083cb8ec22706247645/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

Memoria Política de México. “1882 Tratado de Límites entre México y Guatemala”. Accessed June 3, 2022. http://www.memoriapoliticademexico.org/Textos/5RepDictadura/1882TLG.html

Memoria Política de México. “1894 Ley sobre ocupación y enajenación de terrenos baldíos”. Accessed June 3, 2022. http://www.memoriapoliticademexico.org/Textos/5RepDictadura/1894DSO.html

Memoria Política de México. “Se da a conocer el programa del Partido Liberal Mexicano”. Accessed July 13, 2022. http://www.memoriapoliticademexico.org/Efemerides/7/01071906.html

Memoria Política de México. “1914 Ley de Obreros. Gobierno Constitucionalista del Estado de Chiapas”. Accessed June 6, 2022. https://www.memoriapoliticademexico.org/Textos/6Revolucion/1914-LO-GCh.html

Memoria Política de México. “Surge la Confederación Nacional Campesina CNC”. Accessed June 3, 2022. http://www.memoriapoliticademexico.org/Efemerides/8/28081938.html

Memoria Política de México. “Emiliano Zapata Salazar. 1879–1919”. Accessed June 8, 2022. https://www.memoriapoliticademexico.org/Biografias/ZSE79.html

Memoria Política de México. “Francisco Ignacio Madero González (1873-1913)”. Accessed June 8, 2022. http://memoriapoliticademexico.org/Biografias/MFI73.html

Memoria Política de México. “Francisco Villa (Doroteo Arango Arámbula)”. Accessed June 8, 2022. https://www.memoriapoliticademexico.org/Biografias/VIF78.html

Moguel, Julio. “Reforma constitucional y luchas agrarias en el marco de la transición salinista”. In Autonomía y nuevos sujetos sociales en el desarrollo rural, edited by Julio Moguel, Carlota Botey, and Luis Hernández, 261–275. Ciudad de México: Siglo XXI/CEHAM, 1992.

Olvera, Alberto J. “Las luchas de los cafeticultores veracruzanos: La experiencia de la Unión de Productores de Café de Veracruz”. In Cafetaleros. La construcción de la autonomía. Cuadernos de desarrollo de base 3, 141–155. Ciudad de México: CNOC, 1991.

Pérez Akaki, Pablo. “Las políticas públicas cafetaleras en México: Un análisis histórico”. Investigaciones Geográficas (2013a): 121–143. https://federaciondecafeteros.org/static/files/4LaspoliticaspublicascafetalerasenMexico.pdf

Pérez Akaki, Pablo. “Los siglos XIX y XX en la cafeticultura nacional: De la bonanza a la crisis del grano de oro mexicano”. Revista de Historia, n. 67 (2013b): 159–199. https://www.revistas.una.ac.cr/index.php/historia/article/view/5262

Petchers, Seth, and Shayna Harris. “The Roots of the Coffee Crisis”. In Confronting the coffee crisis: Fair trade, sustainable livelihoods and ecosystems in Mexico and Central America, edited by Christopher M. Bacon, V. Ernesto Méndez, Stephen R. Gliessman, David Goodman, and Jonathan A. Fox, 43–66. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008.

Quirós, Erick. “Modelos institucionales de atención al sector cafetalero en otros países.” Lecture, Taller Producción sostenible de café y biodiversidad en Mesoamérica: retos y perspectivas para reflexionar en México, Oaxaca, October 26-28, 2016.

Renard, Marie-Christine. “Mercado mundial y economía regional. El café en el Soconusco, México”. The International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food, n. 2 (1992): 74–87. https://doi.org/10.48416/ijsaf.v2i.403

Renard, Marie-Christine. Los intersticios de la globalización: Un label “Max Havelaar” para los pequeños productores de café. Ciudad de México: CEMCA, 1999.

Renard, María Cristina. El Soconusco. Una economía cafetalera. Texcoco: Universidad Autónoma de Chapingo, 1993.

Rives Sánchez, Roberto. La reforma constitucional en México. Cuidad de México: UNAM, 2010.

Robles Berlanga, Héctor Manuel. Los productores de café en México: Problemática y ejercicio del presupuesto. Wilson Center, 2011. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/publication/Hector_Robles_Cafe_Monografia_14.pdf

Rodríguez-Centeno, Mabel M. 1993. “La producción cafetalera mexicana. El caso de Córdoba, Veracruz”. Historia Mexicana, n. 1 (1993): 81–115. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25138886

Rodríguez Centeno, Mabel M. “México y las relaciones comerciales con Estados Unidos en el siglo XIX: Matías Romero y el fomento del café”. Historia Mexicana, n. 4 (1996): 737–757. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25139018

Rosales Sierra, Vidulfo. Conflictos por la tierra: Despojo seculiar de los pueblos indios. In Estado de desarrollo económico y social de los pueblos indígenas de Guerrero. UNAM/Secretaría de Asuntos Indígenas del Gobierno del Estado de Guerrero, 2009. https://www.nacionmulticultural.unam.mx/edespig/diagnostico_y_perspectivas/RECUADROS/CAPITULO%206/5%20CONFLICTOS%20POR%20LA%20TIERRA.pdf

SADER. “México vs. la roya del café”. Accessed September 21, 2021. https://www.gob.mx/agricultura/articulos/mexico-vs-la-roya-del-cafe

SADER. “México firme en el combate de la roya del cafeto”. Accessed September 21, 2021. https://www.gob.mx/agricultura/es/articulos/mexico-firme-en-el-combate-de-la-roya-del-cafeto?idiom=es

Sánchez Juárez, Gladys Karina. “Los pequeños cafeticultores de Chiapas. Organización y resistencia frente al mercado”. PhD dissertation, UNICACH, 2015. http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Mexico/cesmeca-unicach/20170419034553/pdf_655.pdf

Toussaint Ribot, Mónica. “Los negocios de un diplomático: Matías Romero en Chiapas”. Latinoamérica (2012): 129–157. https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1665-85742012000200006

Tovar González, Ma Elena. “Extranjeros en el Soconusco”. Revista de Humanidades 8 (2000): 29–43. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=38400802

Villafuerte-Solís, Daniel, and María del Carmen García-Aguilar. “Los empresarios cafetaleros de Soconusco ante la crisis”. In Anuario 1993, 318–341. Tuxtla Gutiérrez: ICHC, 1994.

World Coffee Research. May 1st, 2019. Las variedades del café arábica. Un catálogo global de variedades que abarca: Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Kenia, Malawi, Nicaragua, Panamá, Perú, República Dominicana, Rwanda, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabue: World Coffee Research (WCR). https://varieties.worldcoffeeresearch.org/content/3-releases/20191206-update-may-2019/las-variedades-del-cafe-arabica.pdf

1 Mabel M. Rodríguez-Centeno, “La producción cafetalera mexicana. El caso de Córdoba, Veracruz,” Historia Mexicana, n. 1 (1993): 81–115, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25138886

2 Pablo Pérez Akaki, “Los siglos XIX y XX en la cafeticultura nacional: De la bonanza a la crisis del grano de oro mexicano”, Revista de Historia, n. 67 (2013b): 159–199, https://www.revistas.una.ac.cr/index.php/historia/article/view/5262

3 Fernando Celis Callejas, La Jornada, “Las organizaciones de los cafetaleros,” accessed June 8, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2009/11/14/cafetaleros.html

4 Pablo Pérez Akaki, “Las políticas públicas cafetaleras en México: Un análisis histórico,” Investigaciones Geográficas (2013a): 121–143, https://federaciondecafeteros.org/static/files/4LaspoliticaspublicascafetalerasenMexico.pdf

5 As mentioned in the introduction, the analysis of coffee policies has a national approach. However, this section and the upcoming one, “The Mexican Revolution and President Cárdenas’ Land Distribution,” are mainly focused on the Soconusco region of Chiapas because this region played a key role in expanding coffee during the late XIX and early XX centuries; it attracted international coffee traders; production was based on a large scale; and miserable working conditions encouraged social movement including the Mexican Revolution. These elements allow illustrating a strong contrast with other phases of coffee policies. However, it should be noted that during the late XIX and early XX centuries, policies differed depending on the region. For instance, as illustrated by Pablo Pérez Akaki (2013b), in Veracruz—a relevant coffee region—measures were focused on tax exemption to farmers introducing new plantations, as well as coffee production and consumption taxes. In Oaxaca—another relevant coffee region—coffee incentives included exemption to farmers from arms and war services, as well as money when the number of plants and exports reached a certain level.

6 Maria Elena Martinez-Torres, “Sustainable development, campesino organizations and technological change among small coffee producers in Chiapas, Mexico” (PhD dissertation, University of California, 2003), https://www.proquest.com/openview/e6f39aa3e295f083cb8ec22706247645/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

7 Armando Bartra Vergés, Rosario Cobo, and Lorena Paz Paredes, La hora del café. Dos siglos a muchas voces (Ciudad de México: CONABIO, n.d.).

8 Bartra Vergés, Cobo, and Paz Paredes, La hora del café.

9 Sandra Kuntz Ficker, “El café,” in Las exportaciones mexicanas durante la primera globalización (1870–1929) (Ciudad de México: COLMEX, 2010), 291–344.

10 Luis René Guerrero Galván, “A propósito del aniversario Porfiriano. Una aproximación acerca de las compañías deslindadoras en tiempos del Porfiriato,” Revista Latinoamericana de Derecho Social, n. 22 (2016): 257–268, https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/rlds/n22/1870-4670-rlds-22-00009.pdf

11 “1894 Ley sobre ocupación y enajenación de terrenos baldíos,” Memoria Política de México, accessed June 3, 2022, http://www.memoriapoliticademexico.org/Textos/5RepDictadura/1894DSO.html

12 Rodríguez-Centeno, “La producción cafetalera mexicana,” 85–88.

13 After Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, Mexico and Guatemala disputed the territory of Chiapas. An 1824 plebiscite established that Chiapas would be incorporated into Mexico, but Soconusco remained contested until 1842, when President Santa Ana carried out an armed intervention to incorporate Soconusco into Mexico. However, despite this forced intervention, the territorial limits between Soconusco and Guatemala were not defined until many years later.

14 Mónica Toussaint Ribot, “Los negocios de un diplomático: Matías Romero en Chiapas”, Latinoamérica (2012): 129–157, https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1665-85742012000200006

15 Casey Marina Lurtz, From the grounds up. Building an export economy in southern Mexico (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2019).

16 “1882 Tratado de Límites entre México y Guatemala,” Memoria Política de México, accessed June 3, 2022, http://www.memoriapoliticademexico.org/Textos/5RepDictadura/1882TLG.html

17 Daniel Villafuerte-Solís, and María del Carmen García-Aguilar, “Los empresarios cafetaleros de Soconusco ante la crisis”, in Anuario 1993 (Tuxtla Gutiérrez: ICHC, 1994), 318–341.

18 Alba González Jácome, “Dealing with risk: Small-scale coffee production systems in Mexico,” Perspectivas Latinoamericanas 1 (2004): 1–39, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/236154861.pdf

19 Mabel M Rodríguez Centeno, “México y las relaciones comerciales con Estados Unidos en el siglo XIX: Matías Romero y el fomento del café,” Historia Mexicana, n. 4 (1996): 737–757, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25139018

20 Ma Elena Tovar González, “Extranjeros en el Soconusco,” Revista de Humanidades, n. 8 (2000): 29–43, http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=38400802

21 Names such as Adolfo, Juan, and Guillermo appear to be adaptations of foreign names into Spanish, although I was not able to confirm this through available literature. Furthermore, I was unable to obtain the first name of some farmers, such as von Türckheim.

22 María Cristina Renard, El Soconusco. Una economía cafetalera (Texcoco: Universidad Autónoma de Chapingo, 1993).

23 Bartra Vergés, Cobo, and Paz Paredes, La hora del café.

24 Through the trading companies and Deutsche Bank, German investors had access to almost unlimited loans with an annual interest rate of 6% to 8%, as compared to 24% that farmers paid within Mexico.

25 Marie-Christine Renard, “Mercado mundial y economía regional. El café en el Soconusco, México,” The International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food, n. 2 (1992): 74–87, https://doi.org/10.48416/ijsaf.v2i.403

26 Bartra Vergés, Cobo, and Paz Paredes, La hora del café.

27 A quintal of coffee is equivalent to 250 kilos of coffee cherries, 57.5 kilos of parchment coffee, or 46 kilos of green coffee. The cherry—also known as berry—is the form in which coffee is harvested; parchment coffee is after the pulp and mucilage have been removed, leaving the bean with its parchment or skin; and green coffee is after the parchment of the bean has been removed.

28 Friederike Baumann, “Terratenientes, campesinos y la expansión de la agricultura capitalista en Chiapas, 1896–1916,” Mesoamérica 5 (1983): 8–63, https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4009438

29 Coffee beans may be dried using two methods: 1) the wet method that involves removing the pulp of the cherries with a de-pulping machine, leaving the beans, which are then fermented to remove the surrounding mucilage, and drying the beans; 2) the dry method that involves drying the whole cherries, including their pulp and mucilage. While the former process requires more labor and costs, it results in coffee with a better aroma and more ideal acidity in comparison to the dry method.

30 Renard, El Soconusco, 23.

31 Isabel Avella Alaminos, “Los cafetaleros alemanes en el Soconusco ante el Gobierno de Carranza (1915),” in Anuario 2000 (Tuxtla Gutiérrez: UNICACH, 2002), 445–476.

32 Villafuerte-Solís, and García-Aguilar, “Los empresarios cafetaleros.”

33 Bartra Vergés, Cobo, and Paz Paredes, La hora del café.

34 Vidulfo Rosales Sierra, “Conflictos por la tierra: Despojo seculiar de los pueblos indios,” in Estado de desarrollo económico y social de los pueblos indígenas de Guerrero (UNAM/Secretaría de Asuntos Indígenas del Gobierno del Estado de Guerrero, 2009), https://www.nacionmulticultural.unam.mx/edespig/diagnostico_y_perspectivas/RECUADROS/CAPITULO%206/5%20CONFLICTOS%20POR%20LA%20TIERRA.pdf

35 Enganchador literally means hooker. This person received a commission for each laborer hired, as well as an additional commission based on the total amount of hours that the laborer worked.

36 Villafuerte-Solís, and García-Aguilar, “Los empresarios cafetaleros.”

37 These stores within the estates were called raya stores, given that due to illiteracy, laborers were asked to draw a raya (line) on a piece of paper upon being paid their tokens.

38 INEHRM, Lázaro Cárdenas: Modelo y legado. Vol. II (Ciudad de México, 2020).

39 All local currencies have been converted to dollars, with the exception of those mentioned in this section and the section of this paper titled The Mexican Revolution and President Cárdenas’ land distribution as they pertain to centuries ago, and it is, therefore, difficult to establish a meaningful exchange rate.

40 Renard, El Soconusco, 30.

41 Friederike Baumann, “Terratenientes,” 22.

42 Renard, El Soconusco, 30.

43 Bartra Vergés, Cobo, and Paz Paredes, La hora del café.

44 Renard, El Soconusco, 43.

45 Renard, El Soconusco, 31.

46 The enganchador had to pay for a license, plus Mex$1.55 for each contract signed. Each laborer introduced to Soconusco generated a tax of Mex$0.30 to the municipality.

47 Bartra Vergés, Cobo, and Paz Paredes, La hora del café.

48 “Se da a conocer el programa del Partido Liberal Mexicano,” Memoria Política de México, accessed July 13, 2022, http://www.memoriapoliticademexico.org/Efemerides/7/01071906.html

49 “Francisco Ignacio Madero González (1873–1913),” Memoria Política de México, accessed June 8, 2022, http://memoriapoliticademexico.org/Biografias/MFI73.html

50 “Francisco Villa (Doroteo Arango Arámbula)”, Memoria Política de México, accessed June 8, 2022, https://www.memoriapoliticademexico.org/Biografias/VIF78.html

51 “Emiliano Zapata Salazar. 1879–1919,” Memoria Política de México, accessed June 8, 2022, https://www.memoriapoliticademexico.org/Biografias/ZSE79.html

52 Roberto Rives Sánchez, La reforma constitucional en México (Cuidad de México: UNAM, 201).

53 “1914 Ley de Obreros. Gobierno Constitucionalista del Estado de Chiapas,” Memoria Política de México, accessed June 8, 2022, https://www.memoriapoliticademexico.org/Textos/6Revolucion/1914-LO-GCh.html

54 Renard, El Soconusco, 38.

55 Renard, El Soconusco, 52.

56 Bartra Vergés, Cobo, and Paz Paredes, La hora del café.

57 Renard, El Soconusco, 45.

58 Renard, El Soconusco, 65.

59 Villafuerte-Solís, and García-Aguilar, “Los empresarios cafetaleros.”

60 Renard, El Soconusco, 64.

61 INEHRM, Lázaro Cárdenas, 229.

62 Lázaro Cárdenas conceived the ejido as collectively owned land, which was inalienable, imprescriptible, and lifelong. Ejido members lost the right to use the land if they did not work it, rent it for others to farm, or hire others to work the land.

63 INEHRM, Lázaro Cárdenas, 593.

64 Jorge J. Gómez de Silva Cano, El derecho agrario mexicano y la Constitución de 1917 (Ciudad de México: SEGOB/CULTURA/INEHRM/UNAM, 2016).

65 In 1938, the Partido Nacional Revolucionario became the Partido de la Revolución Mexicana (Mexican Revolution Party), and in 1946 the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (National Institutional Party [PRI]), which is still active.

66 INEHRM, Lázaro Cárdenas, 592–599.

67 “Surge la Confederación Nacional Campesina CNC”, Memoria Política de México, accessed June 3, 2022, http://www.memoriapoliticademexico.org/Efemerides/8/28081938.html

68 Governor Tiburcio Fernández Ruíz (1920–1924) distributed 20,000 hectares; Carlos Vidal (1925– 1926) distributed 87,067 hectares; and Raymundo Enríquez (1928–1929) distributed 192,517 hectares.

69 Renard, El Soconusco, 71.

70 Renard, El Soconusco, 68–69.

71 Renard, El Soconusco, 66–68.

72 In 1942, the Mexican state confiscated 66 estates, and although they were returned to their owners in 1946, crops, equipment, and roads had deteriorated.

73 Villafuerte-Solís, and García-Aguilar, “Los empresarios cafetaleros.”

74 María del Carmen García Aguilar, Daniel Villafuerte Solís, and Salvador Meza Díaz, “Café y neoliberalismo. Los impactos de la política cafetalera en el Soconusco, Chiapas,” in Anuario 1992 (Tuxtla Gutiérrez: ICHC, 1993), 285–302.

75 Renard, El Soconusco, 79.

76 Hubert C. de Grammont and Horacio Mackinlay, “Las organizaciones sociales y la transición política en el campo mexicano”, in La construcción de la democracia en el campo latinoamericano, edited by Hubert C. de Grammont (Buenos Aires, Argentina: CLACSO, 2006), 23–68.

77 Decreto que crea la Comisión Nacional del Café, October 21, 1949, DOF, https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_to_imagen_fs.php?codnota=4572370&fecha=21/10/1949&cod_diario=195809

78 Erick Quirós, “Modelos institucionales de atención al sector cafetalero en otros países” (Lecture, Taller Producción sostenible de café y biodiversidad en Mesoamérica: retos y perspectivas para reflexionar en México, Oaxaca, October 26–28, 2016).

79 Bartra Vergés, Cobo, and Paz Paredes, La hora del café.

80 During the Second World War, European markets closed and Latin American coffee producers principally depended on the market in the United States. In order to avoid a price collapse, 15 countries of the Americas signed, in 1940, one of the first accords which aimed to regulate coffee production, the Interamerican Coffee Agreement. Later accords regulating coffee production included the Gentleman’s Agreement (1954), the Agreement of Mexico (1957), and the Latin American Coffee Agreement (1958); however, these agreements did not include the majority of countries worldwide involved in the coffee sector. With the 1962 ICA agreement, most coffee-producing and consuming countries worldwide agreed not only to regulate coffee production but also to maintain prices within a given range. Through the ICA, member countries also agreed to establish the International Coffee Organization (ICO) to oversee regulation of the sector.

81 Pablo Pérez Akaki, “Los siglos,” 198–199.

82 I refer to kilos as a unit measurement for coffee, except when referring to the international coffee prices, given that the ICO uses pounds.

83 Fernando Celis Callejas, La Jornada, “El TLCAN y la cafeticultura mexicana,” accessed June 7, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2013/11/16/cam-cafe.html

84 Gladys Karina Sánchez Juárez, “Los pequeños cafeticultores de Chiapas. Organización y resistencia frente al mercado” (PhD dissertation, UNICACH, 2015), http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Mexico/cesmeca-unicach/20170419034553/pdf_655.pdf

85 Bartra Vergés, Cobo, and Paz Paredes, La hora del café.

86 Seth Petchers and Harris Shayna, “The Roots of the Coffee Crisis,” in Confronting the coffee crisis: Fair trade, sustainable livelihoods and ecosystems in Mexico and Central America, edited by Christopher M. Bacon, V. Ernesto Méndez, Stephen R. Gliessman, David Goodman and Jonathan A. Fox (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008), 43–66.

87 Luis Hernández, “Cafetaleros: Del adelgazamiento estatal a la guerra del mercado,” in Autonomía y nuevos sujetos sociales en el desarrollo rural, edited by Julio Moguel, Carlota Botey y Luis Hernández (Ciudad de México: Siglo XXI/CEHAM, 1992a), 78–97.

88 Fernando Celis Callejas, La Jornada, “Las organizaciones de los cafetaleros,” accessed June 8, 2022,

https://www.jornada.com.mx/2009/11/14/cafetaleros.html

89 Ley Federal de Reforma Agraria, Act of April 16, 1971, DOF.

90 Ley General de Crédito Rural, Act of April 5, 1976, DOF.

91 Mexico’s coffee production increased from 126,616 tons of green coffee in 1961 to 343,440 tons in 1989, decreasing to 158,308 in 2018. Similarly, coffee exports increased from 89,222 tons of green coffee in 1961 to 265,919 tons in 1989, decreasing to 113,354 in 2018. As the earliest available data from FAOSTAT is from 1961, statistics regarding the first 3 years of INMECAFE (1958 to 1960) could not be included.

92 “Cultivos y productos de ganadería,” FAO, accessed November 16, 2023, https://www.fao.org/faostat/es/#data/QCL

93 Luis Hernández, “Café: Privatización y concertación social,” El Cotidiano 38, (1990): 53–58. https://www.ceccam.org/node/349

94 Bartra Vergés, Cobo, and Paz Paredes, La hora del café.

95 Alberto J. Olvera, “Las luchas de los cafeticultores veracruzanos: La experiencia de la Unión de Productores de Café de Veracruz,” in Cafetaleros. La construcción de la autonomía. Cuadernos de desarrollo de base 3 (Ciudad de México: Coordinadora Nacional de Organizaciones Cafetaleras [CNOC], 1991), 141–155.

96 Martinez-Torres, “Sustainable development”, 93–115.

97 Sánchez Juárez, “Los pequeños cafeticultores de Chiapas”, 93–93.

98 These disagreements include: 1) Brazil, the world’s largest coffee producer (25% of all coffee harvested), refused to have its quota reduced despite the fact that its productive capacity had been affected by a 1986 frost, while Central American countries, Mexico, and Indonesia demanded higher quotas due to increased production and because storing coffee involved high costs as well as great loss of profits. For instance, Mexico’s quota of global coffee commerce was 4.1%, or 2.1 million sacks, although it produced 5 million sacks. Storing these reserves cost Mexico US$500 million. 2) While producer countries considered the minimum price established by the agreement to be very low, consumer countries refused to raise it. 3) Aside from the ICA, a black market prevailed in Eastern Europe where coffee was traded at lower prices; this discouraged some member countries from maintaining a regulatory framework.

99 Renard, “Mercado mundial”, 77–78.

100 Fernando Celis, “Unión de Productores de Café de Veracruz. Del cambio de terreno al fortalecimiento de una organización democrática”, in Cafetaleros. La construcción de la autonomía. Cuadernos de desarrollo de base 3 (Ciudad de México: CNOC), 1991.

101 Marie-Christine Renard, Los intersticios de la globalización: Un label “Max Havelaar” para los pequeños productores de café (Ciudad de México: CEMCA, 1999).

102 Seth Petchers and Shayna Harris, “The Roots of the Coffee Crisis,” in Confronting the coffee crisis: Fair trade, sustainable livelihoods and ecosystems in Mexico and Central America, edited by Christopher M. Bacon, V. Ernesto Méndez, Stephen R. Gliessman, David Goodman, and Jonathan A. Fox, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008), 43–66.

103 Hernández, “Café”, 53–58.

104 Albert Folch, and Jordi Planas, “Cooperation, fair trade, and the development of organic coffee growing in Chiapas (1980–2015)”, Sustainability, n. 2 (2019): 2–22, https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020357

105 Hubert C. de Grammont, Horacio Mackinlay, and Richard Stoller, “Campesino and indigenous social organizations facing democratic transition in Mexico, 1938–2006”, Latin American Perspectives, n. 4 (2009): 21–40, https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X09338588

106 Julio Moguel, “Reforma constitucional y luchas agrarias en el marco de la transición salinista,” in Autonomía y nuevos sujetos sociales en el desarrollo rural, edited by Julio Moguel, Carlota Botey and Luis Hernández (Ciudad de México: Siglo XXI/CEHAM, 1992), 261–275

107 Bonifaz Chapoy, Dolores Beatriz, Planeación, programación y presupuestación (Ciudad de México: UNAM, 2003).

108 Angélica Enciso, La Jornada, “El Congreso Agrario Permanente: ¿10 años no es nada?”, accessed June 8, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/1999/05/25/cam-agrario.html

109 Arturo García, “Proceso de construcción del movimiento campesino en México: La experiencia de la CNOC,” in Cafetaleros. La construcción de la autonomía. Cuadernos de desarrollo de base 3 (Ciudad de México: CNOC, 1991), 9–16.

110 Aurora Cristina Martínez Morales, El proceso cafetalero mexicano (Ciudad de México: UNAM, 1996).

111 Fernando Celis Callejas, La Jornada, “Las organizaciones de los cafetaleros”, accessed June 8, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2009/11/14/cafetaleros.html

112 De Grammont and Mackinlay, “Las organizaciones.”

113 Silvia Jurado Celis, and Armando Bartra Vergés, “Cómo sobrevivir el mercado sin dejar de ser campesino. El caso de los pequeños productores de café en México”, Veredas: Revista del Pensamiento Sociológico Especial (2012): 181–191, https://veredasojs.xoc.uam.mx/index.php/veredas/article/view/511

114 Luis Hernández, “Las convulsiones rurales,” in Autonomía y nuevos sujetos sociales en el desarrollo rural, edited by Julio Moguel, Carlota Botey, and Luis Hernández (Ciudad de México: Siglo XXI/CEHAM, 1992b), 235–260.

115 Fernando Celis Callejas, La Jornada, “La CNOC: Una organización cafetalera independiente”, accessed September 22, 2021, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2015/08/15/cam-cnoc.html

116 De Grammont and Mackinlay, “Las organizaciones.”

117 Normas de operación de la Alianza para el Campo 1998, para los Programas de Fomento Agrícola, Ganadero, de Desarrollo Rural y Sanidad Agropecuaria, June 3, 1998, DOF, https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=4881535&fecha=03/06/1998#gsc.tab=0

118 Lineamientos específicos del Proyecto Transversal Componente Fomento Productivo del Café, 2011, 31 de agosto, DOF, https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5207227&fecha=31/08/2011#gsc.tab=0