Revista Letras N.° 77

Enero-Junio 2025

ISSN 1409-424X; EISSN 2215-4094

Doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.15359/rl.1-77.1

URL: www.revistas.una.ac.cr/index.php/letras

|

Biostory as Indigiqueer Resistance in Indigenous Futurism1 (Biohistoria como resistencia indígiqueer Monica Bradley Harvey2 Universidad de Costa Rica, Sede Rodrigo Facio, San José, Costa Rica |

Abstract

This essay offers a critical reflection mirroring the book of creative essays Making Love with the Land (2022), by Joshua Whitehead. It defines three concepts within contemporary Indigenous literatures: biostory, Indigiqueer, and Indigenous futurism, braiding a politicized, sovereign writing style within the book. It examines how the concept of biostory functions to help Indigenous, queer and other peoples imagine different ways of being in real/possible apocalyptic present/futures. Queer Indigenous futurisms and Indigiqueer writing disrupts linear conceptualizations of space, time and identity, weaving organic, spiritual, and scientific elements in the construction of self and other.

Resumen

Este ensayo ofrece una reflexión crítica que es un espejo del libro de ensayos creativos Making Love with the Land (2022), de Joshua Whitehead. Define tres conceptos dentro de las literaturas indígenas contemporáneas: biohistoria, indigiqueer y futurismo indígena, entrelazando un estilo de escritura soberano y politizado dentro del libro. Examina cómo el concepto de biohistoria funciona para ayudar a los pueblos indígenas, queer y otros a imaginar diferentes formas de ser en presentes/futuros apocalípticos reales/posibles. Los futurismos indígenas y la escritura indigiqueer alteran las conceptualizaciones lineales del espacio/tiempo e identidad, tejiendo elementos orgánicos, espirituales y científicos en la construcción del yo y del otro.

Keywords: Indigenous literatures, queer theory, Indigenous futurism, Two-Spirit

Palabras clave: literaturas indígenas, teoría queer, futurismo indígena, dos espíritus

I was stopped in London when I felt it coming down. Crashing all around me with a great triumphant sound. Like the damn was breaking and my mind came rushing in…This time I know I’m fighting. This time I know I am back in my body.

Maggie Rogers3

For Charity, this one we wrote together…

I begin this essay with “Back in My Body,” by Maggie Rogers as I, like Joshua Whitehead, listen to that song on repeat. Since I quit drinking over a year ago, it has become an anthem to ease the return to myself after retreating into a haze of alcohol for the last twenty years. In fact, many of the songs Whitehead references his collection of creative non-fiction essays, Making Love with the Land4 have been the soundtrack to my own recovery. I share this because the writing of biostory demands vulnerability, an offering of oneself for voyeuristic consumption that extends beyond the word to the corporal, to the pain and joy, as well as the structures of power that encapsulate these lived temporalities (21). It requires a sacrifice of one’s privacy and ego to break away from the guarded writing of settler colonial, heteropatriarchal academia and the objective mind detached from subjective corporality that characterizes these institutions; as subjective corporealities often fuel the writing of “subaltern” authors, the demand to “disappear” bodies and subjectivities also restricts access to academic spaces and writing itself.

As Whitehead argues, the physical body “will always be tied to the body of text we create” especially for BIPOC, disabled, queer, and/or women authors (74): “My existence has and will always be a radical act of political livelihood, so much that when I write, I write from the body, proprioception; story is attached to me integrally, umbilically, and we feed and nourish each other like regurgitant birds” (74). Biostories animate stories through political and oratory texts that refuse confinement within a genre, style or categorization. As such, in the collection of “skinstories” in this book, Whitehead, a Two-Spirit Oji-Cree author, dispels the dualisms of mind/body, fiction/theory, and human/nature: “the body always knows better than the mind does; muscles remember, they witness, like trees, riddles etch disease, and I am weeping willow, crying seeds and dripping saline from my hair” (1). He begins his biostory sitting under the sun in the hills of Dover, Canada listening to Maggie Rogers, while I, a lesbian, non-Indigenous American-Costa Rican woman, listen to the same song under the same sun on the other side of the continent also connecting with the “child-me who still fits inside me” (24). I am only now remembering who that child was without the anesthesia of wine-induced slumber. Whitehead, similarly, reaches for the NyQuil to quell his dreams that haunt him “in the current ecological and political end-times climate of the globe” (24). He continues questioning, “What better way to forewarn about the machinery of colonialism than in the animated cooing of such dreams; and what better way to foreground the emergence of joy in the bridge between loss and becoming?” (24). I am learning to emerge like a molting cicada, to dream again.

This essay explores how the writing of biostories allows for both Whitehead and the readers to simultaneously experience the poetry/science that permeate their bodies in a spiritual existence within a political reality. In his writing, pain and mourning as well as joy and creation, transcend and extend the delineations of the body into the landscapes that surround them rather than reaffirming an artificial boundary between self and other, whether those others include bears, bacterium or semi-colons. While Whitehead and I might be beginning to feel “back in our [bodies],” humans do not end at the skin and certainly not at the mind nor words on a page. Thus, this essay examines how the biostories in Making Love with the Land function as biotech for Indigiqueer writing and post-dystopian becomings that can help Indigenous, queer and other peoples imagine different ways of being in real/possible apocalyptic present/futures.

Biostory exemplifies a particular style of writing within Indigenous futurism in which authors create texts as “animate beings” and “place them into oratories of history and ‘futurity’” to “conceptualize our fantastical dreams as very real decolonized futures” (22). Whitehead writes of both the body/writing as a form of biotechnology that he integrates into the identity of Indigiqueer. Writing the body has its foundations in French feminist theory from the 1970s including the work of Cixious, Irigaray and Kristeva. For instance, in Cixious’ article “The Laugh of Medusa,” she argues women must write themselves into the texts with all of their senses, to return to the body what was taken by patriarchy and write outside of phallocentrism, outside of the “lack,” through the creation/connection with a feminine style of writing to find the dark continent5. Likewise, Irigaray calls for écriture féminine to disturb patriarchal linear and logical writing that “others” women by writing from the disruptive place of otherness itself.6 Of course, these writings are now criticized as essentializing women’s bodies and reducing them as middle-class, cis-gendered, white women, demonizing all masculinities; they are criticized for offering a simple reversal rather than a displacement of patriarchal writing, itself written through dense theory that marginalizes many “women.” Biostories, as proposed by Whitehead, offers a more nuanced and resistant virus to the system.

The three concepts explored here, biostory, Indigiqueer, and Indigenous futurism, intertwine throughout Whitehead’s work braiding a politicized, sovereign writing style that resists the borders and boundaries of not just gender but also both academic categorization and nationhood: Whitehead writes, “Insomuch as the future of Indigiqueer is ours for the making, we define it in our own terms, sovereignly, singularly, and collectively” (6). Biostory, or bodybooks, likewise, blur and implode the boundaries of genre (autobiography, fiction, poetry, prose, theory) and traditional Western settler colonial binary divisions (mind/body, human/animal, animal/machine, science/spirituality, man/woman). This disruption/refusal opens the texts up for misreading within the lines of settler colonialism and heteropatriarchal categorizations, but rather than acquiesce, it rejects identification within these terms: “I am Indigenous and gendered beyond Western understandings, beyond sex and nation and nuclear categorizations…I take offense at the impulse to try to identify my writings” (78).

Biostories also reference the concepts of biopower and biopolitics by Foucault. Biopower, for Foucault, is the harnessing of the political power that controls populations through in investment in “life” while simultaneously disciplining these same bodies. Yet it has no real interest in the lives of actual people, only the power of the state and capitalism; its true interest was never to ensure life but to turn bodies into machines that can be controlled and regulated.7 Biopolitics represents a move from a sovereign power that needed to be protected to a society that must be defended through an investment in “life” (and elimination of those who are represented as a threat to it). While Foucault does attribute the rise of biopolitics to the creation of state racism, Mbembe8 critiques his work for not examining the intricate workings of power and domination which decide who will live and who must die, which he calls necropolitics. Nationalism, race, sex, class, sexuality, and many more categories of marginalized identities are all inscribed within this system of biopower that decides which lives have value and which are a “threat” to life itself, thus, controlling whose stories, voices, and bodies can be heard/seen and whose must disappear. Biostory, then, writes the body of individuals, connected to communities, within a biopolitics/necropolitics that would rather these bodies be disciplined or dead within the same system; it rules them dangerous, as is women’s writing in écriture féminine. Biostories, then, fight for the right to creatively express themselves as a sovereign, decolonial, feminist, and queer writing technology from a place of ownership of the bodies, experiences, and knowledges that the settler-colonial state would eradicate.

Whitehead explains how the self-narration of autobiography is always imbued with nationhood inside a settler-colonial context as it strives to freeze and solidify the representations of Indigeneity and trap it within the singular story of a nation: “if autobiography is the poetics of belonging in a Canadian context, biotexual writing seeks to disobey and demarcate that belonging and subservience” (79). Thus, biotexts write new ways of being into existence to resist autobiography as “obituary” and “indigeneity as flora and fauna” (78). Rather biostories return to the past to look towards the future/present with the hope of possibility and the promise of movement that resists Indigenous death and stagnancy of queer Indigenous realities in space and time. By affirming life even in the biopolitical workings of power of the setter-state, it resists the necropolitics of Indigenous and queer erasure as a disposable population that can suffer multiple types of death9 by writing the body back into texts and making queer Indigenous lives both viable and grievable.10 Thus, language and storytelling transform the actual world around us.

Reading texts through Indigenous futurism disconnects certain concepts from Western frameworks and provides entirely divergent perspectives: How we understand bodies, what is considered “real” and “realism,” and the meaning of dreams themselves hold different significations within Indigenous epistemologies and, thus, require different methodologies. Indigenous futurism proposes new methodologies for reading and has held an important place in recent Indigenous literature. Grace Dillon coined the term Indigenous futurism in 2003 to describe this new artistic and literary movement in her book Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction. She writes that Indigenous futurisms “involve discovering how personally one is affected by colonization, discarding the emotional and psychological baggage carried from its impact, and recovering ancestral traditions in order to adapt in our post–Native Apocalypse world.”11 Yet it is not simply Indigenous science fiction or fantasy, but artistic creation rooted firmly in the bodies, minds and spirits of Indigenous peoples: They are true and real in themselves, sometimes more so than what is commonly understood as “reality.” It relates closely to afro-futurism, but while Indigenous futurism may represent a relatively new literary cannon, Indigenous knowledges and storytelling have always been future-oriented, dynamically linking the past, present, and future. Thus, Indigenous futurism celebrates the triumph of endurance and resists colonial narratives of death (necropolitics). It imagines viable future for all people but particularly Indigenous peoples, and in the case of the writing Whitehead, Indigiqueer people, who continue to survive and affirm life against the attempted apocalypses through their art.

Through Indigenous futurism, Whitehead explores how to write decolonial/sovereign imaginings within the confines of academia and rejects the divisions of body/land/animal that Indigenous peoples have always celebrated as part of a connected unity within the universe: in nêhiyâwewin ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ, the Cree language meaning to love one another, natural “objects” (rocks, water, fire, air) are animate, imbued with spirit, and part of a greater circular kinship order; each of these essences have subjectivities reflected in nêhiyâwewin ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ, while in English, these same “objects” are dead, raw materials only valuable in their utility for humans with no sense of reciprocity. This lack of reciprocity with nature and the land, then, adds another layer of the politics of death of the settler-state which biostories counter; it affirms life in all things (68). In the worldview of wahkohtowin, from fungi to animals to trees to water, we are all related as kin and accountable to each other: humanity does not exist within a hierarchical relationship with other beings on the Earth. Thus, when discussing bodies, he includes more than the flesh and bone “zippers,” but also “bodies of land, water, literature, our communities” that expand out from and are contained within our own skin and, without which, we will all die (88). Whitehead explains “living stories” through embodiment of land, water, and trees:

My elders tell me that when we set foot on a piece of land—again a body—we simultaneously experience the past, present and future… the land is an archive, is a library, is a genealogy—a body of land is a body of literature. Water remembers, it maintains memories, it recalls substances it has previously dissolved…if the land can witness, it too can listen. (89)

Similar to the conceptualizations of bodies, what is considered “real” and “reality” varies in the Cree worldview. Much Indigenous writing is considered mythology or fantasy lacking scientific objectivity and significance. Thus, when Whitehead insisted on including dream sequences in his novel Johnny Appleseed,12 he was told it distracted from the realism of the novel, while Whitehead argues that these dreams were more real than the hellish “reality” Johnny lived as “a queer-femme-Indigenous nâpew” (68). Dreams are not mere metaphors but rather integral to Indigenous knowledges, realities, and epistemologies: “They instruct us as we embody ourselves or others as avatars; they mend us, heal us, warn and rejuvenate us” (68). They literally function as lifelines in the same way as storytelling: They both create and are reality.

As we can see, biostories resist the private ownership of “real” and “reality” presented through settler-colonial institutions, literary cannons, and academia in general. They rebel against Indigenous peoples being objects of study or trapped in “the prison house of the ‘then’” by animating bodies such as lands, trees, waters, ancestors, magic, dreams, visions, and animals and releasing them in the present/future (102). Likewise, Whitehead webs Cree concepts, worldviews, and terminology throughout his texts to animate his Indigenous language in his writing as well. By rejecting or expanding “objective” settler knowledges, Indigenous futurist writing breaks open the gates of literature and literary nationalism and fights the stereotypes of Indigenous stories as pulp fiction, past history, or mythology: as Whitehead asks, “what is the use of realism in Indigenous literatures when its realities are misinterpreted as fodder for idyllic and frontier fantasies”? (103). As such, bodies, lands, dreams and texts intertwine in new becomings in Indigenous futurism and biostories.

Like dreams and our relationship with nature, pain, and mourning also construct a vital part of biostories. For instance, in his bio-story “I Own a Body That Wants to Break,” Whitehead speaks of his struggle with eating disorders as a queer, Indigenous fat body in a patriarchal, homophobic settler colonial context: he writes of the polluted Gimli reservoir as a metaphor for his body: “I think of my body like that reservoir, riddled with stains from words like ‘savage’ and ‘faggot.’ All that waste coagulates into a mound of defecation…that poisons its host, one that cries to be expunged” (19). As I read his struggle to expunge the pollution of this world, I immediately begin to mourn my best friend who died from anorexia/alcoholism twelve years ago. Whitehead writes, “Bulimia and anorexia are siblings…they hold your hand and guide you into the deepest recesses of your psyche; they don’t let you have your own subconscious, they make you sleep in their bed” (119). My friend, Charity, never made it out of this bed.

As I read Whitehead’s story, I remember the last time I wrote about Charity: I was applying for my first teaching job as a graduate student in Women’s Studies and I wrote truthfully of why I wanted to teach, intertwining Charity’s story with my own: She had taught me everything I knew about queer and feminist theory. A professor later used it, nameless, as an example for other graduate students applying for the job the following year. Over drinks, I heard one of those students laughing at my essay (not knowing I had written it) saying how pathetic it was, that the author could not tell their own story but relied on their dying friend’s story. Her laughter still haunts me making me question the choice to “bloodlet” in writing as biostories ask of us (92). As Whitehead writes, “I must remember a story can be eaten like a body” (85). Yet, she touched a nerve: Since getting that teaching job while my friend was dying, I have felt like cannibal, feared being overtaken by Wendigo, devouring my friend’s knowledge the same way her body ate away at itself.

When I met Charity, she was a graduate student teacher while I was just starting college. All 72 pounds of her with hospital bracelets still on her wrists was in deep concentration reading feminist and queer theory at a local college bar on ladies’ night (for the free beer, of course), and, intrigued, 18-year-old me drinking free beer with my fake ID, left my group of lesbian friends to speak to this person who seemed so out of place, and my world was never the same. Immediately, she sustained my own hunger for connection with theory, literature, music, and compassion. While I am now choosing to overcome my own alcohol use issues, I carry a feeling of debt while her spirit laughs at me for choosing “wellness” in loving jest: not the cruel laughter of my fellow grad student but that of someone who respects my becoming but also knows how hard of a choice it is; there’s nothing to do but laugh.

Biostories are intertextual, we are all cannibals feeding off the dead/living: My friend’s biostory still provides me sustenance, her words still nourish my spirit, still write this story. In wellness, I hope to provide an apt dwelling for her memory. Whitehead explains of wellness:

There are days when I look in the mirror and I see me in my entirety: ravishing, intelligent, accomplished, an ancestral nebula of light pounded from a star. I am told the formation of a galaxy, a star-birthing, is the same process we undergo in the womb—that our formation is a mirroring of one another. I remind myself in these downtimes that I am galactic in my wellness. (114)

If human birth mirrors the birth of stars, Charity’s death was a supernova creating an explosion a billion times brighter than the sun, forming new galaxies in its wake: In her honor, I am also trying to be galactic in my healing even when it feels strange and sticky to treat my body as a world-maker (121). Thus, biostories share their own pain with the readers.

Whitehead shares his break-ups, the loss of family members, struggles with mental health, the pain of the pandemic, and the grief around institutionalized Indigenous and queer death, which many of us can relate to, especially BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, people of color), disabled, queers and women. For instance, in “Who names the Rez dogs Rez,” he animates a rez dog (the stray dogs that live on Indigenous reservations) as a sacred teacher revealing the promise of futurity: “I am the one removed from the servitude of civility and I return to the hinterland of who I am: child-me, elder-me, present-me all dancing vigorous round steps in this pit I call pimatisowin, the act of living. I love the me I become in orality” (6). These animations give us tools for survival in the apocalypse and ways in which queer Indigeneity can offer new models of relationality that we need in this current configuration of space and time to save our planet.

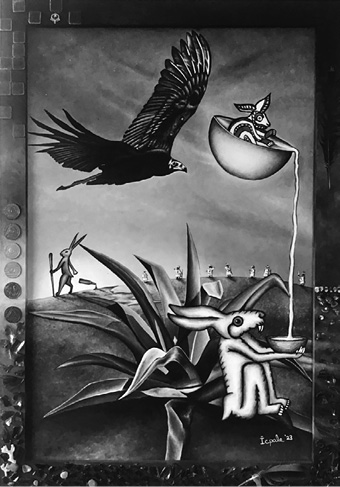

He also discusses how writing itself is a form of mourning for him as he grieves the loss of a cherished aunt. He questions how to mourn without causing harm, without getting stuck, overindulging on pain and becoming possessed by it. I know this question all too well. I also struggle with it. Charity held pain like a possession and the mourning consumed her; she ate pain, story, and memory and it ate her body in return. Yet, in his mourning of his aunt, he animates her as a fierce wolverine that has “no business with hauntology” (143). Wolverines “eat the dead: spiritual carrion, ones who take from me the parts that are decaying…who eat pain rather than cause it” (146). As I have been learning to heal my own pain and not become consumed by it, the Zopilote (vulture) has been my animal ally. While writing this essay I animated the Zopilote and our journey through a painting (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The Dance of Olo/Tzopilot. Oil on canvas

Source: author’s own painting (2023)

The Zopilote, like the wolverine, is also a pain-eater who digests and dissolves wounds, but after, it glides and sails almost effortlessly into the sky with an acute sense of vision and smell. In Bribri origin stories from Costa Rica, the Zopilote (Olo) helped construct the great house of the Earth with Sibü, singing the first sorbón or song of creation13. He is enlisted by Sibü to keep our house clean and to purify the rivers. Hence, while in settler mythology, the Zopilote carries negative associations of greed and death, for me, the Zopilote is an animal of service and humility who provides hope that after cleansing the decay of that which is no longer useful, we might fly effortlessly with a new lightness and perspective and laugh. Whitehead discusses how in his community laughter is a magical healing and coping tool, an exorcism, and that laughing at funerals is a common occurrence (147). It is in the balance of grief and joy that we can find our “center,” our “origin spot,” and the place we can sing and create from. These lived knowledges are valid as well: I have learned much observing the Zopilote: They carry thousands of stories and lessons from over centuries in their bodies. Likewise, the wolverine protects Whitehead as it protected his aunt: “And ain’t that the grandest laugh?” (146)

Two-Spirit and Indigiqueer Identities

Indigiqueer and Two-Spirit are sister identities which integrate Indigenous sovereignty, spiritualities, and worldviews in ways which diverge from settler-colonial conceptualizations of queerness and often un-settle what queerness represents: As Whitehead reveals both identities resist the “settler-colonial, hierarchical, capitalist project” (86) and define queerness “outside of cisness, masculinity, whiteness, thinness” (45). While much of queer history is indebted to black, brown, trans and non-binary resistance to white hetero-capitalist patriarchy, like Indigenous queerness, hegemonic white queerness subjugates these histories and corporealities, and the racism and sexism of hegemonic cultures still prevail in many queer spaces and writing. Whitehead asserts, Two-Spirit:

means much more than simply my sexual preference within Western ways of knowing, but rather that I am queer, femme/iskwewayi, male/nâpew, and situated this way in relation to my homelands and communities. I state this because queerness, or settler sexualities, has stolen so much from Two-Spiritness—I am sovereign through what sovereignty calls me. (38)

Thus, through the mere act of asserting their existence, queer Indigeneity and Two-Spiritness in themselves become acts of resistance, ceremonies of being and life, in the face of the necropolitics of the settler-state, in Indigenous futurisms, also known as apocalypses in the past, present, and future. As Whitehead declares, “If Indigeneity is a vanishing act, it’s one we’ve perfected to ghost ourselves into the future, just ask…all those Two-Spirit hero(in)es who learned to love beyond body, space and time” 36). He is referring to both animated hero(in)es of stories, like the stories he writes, as well as the incarnated people who have fought for Two-Spirit identities and survival in this space-time dimension and those who continue to fight and expand Indigenous queerness like the identity of Indigiqueer.

While the two identities carry much of the same resistance to settler-queerness, they vary slightly in their conceptualizations of identity in space/time. Two-Spiritness, a self-named collective identity for LGBTQI Indigenous peoples, invokes and celebrates the identities and gender and sexual expressions within many traditional Indigenous languages and spiritualities and rescues these from the attempted eradication by settler-colonialism since the first colonists arrived on Turtle Island in 1491. This attempted annihilation (the first apocalypses) continues through the centuries through the imposition of laws, genocidal policies, forced Christianization, the residential/boarding schools in North America, the destruction of the land and habitats, and the indifference to and support of Indigenous death that we continue to observe in contemporary society. To resist this invisibilization/attempted eradication, gay, lesbian, bi, trans and queer Indigenous peoples termed the identity Two-Spirit in the 1990s to replace the offensive, outdated term, berdache which was used by French and English settler-colonialist (and later appropriated and disseminated by North American academics and universities). The settler-colonists used the term berdache to refer to Indigenous tribal members who lived outside of Western binary sexual and gender norms, or members dressing or acting like “the other sex,” for which they were repulsed and disgusted.

For instance, Whitehead references a cartoonish painting by George Catlin in the mid-1800’s called Dance to the Berdash where Catlin ridicules a ceremonial dance in honor of a Two-Spirit member of the Sac and Fox tribes. The painter describes the ceremony as “one of the most unaccountable and disgusting customs that I have ever met in the Indian country... I should wish that it might be extinguished before it be more fully recorded” (52). Nevertheless, many anthropologists and other academic researchers also later utilized the term berdache as an example of the naturalness of sexual and gender diversity and to promote more LBGTQI acceptance within society. Yet despite their good intentions, their use of term still suspended the “berdache,” as a practice/identity of the past within “a romantic idealization of queer Indigeneity” and as an example of Indigeneity as “nature” unaffected by culture (39). Indigiqueer, on the other hand opposes the fossilization of Two-Spirit identify and connects the past with the present “realities” and futurity. Yet with either identity, like Whitehead reveals, the love and affirmation of queerness, Indigeneity, and their intersection is political act.

The paintings by Kent Monkman, a Swampy Kree Two-Spirit illustrate Indigiqueer identity and its intersection with Indigenous futurism and biostory in art, as he celebrates Two-Spirit identity through a playful and deliberately performative representations of the past but taken into the present/future. In particular, in one painting and performance piece, he responds to the settler-colonial painting Dance to the Berdash through an installation at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. In this piece, his alter-ego Miss Chief Testickle, his alter-ego, dances the role of the “berdashe” through a choreography based on traditional pow-wow and contemporary dance.14 As Halberstam writes:

Monkman deploys a decolonial strategy fighting fire with fire, noise with noise, cacophony with cacophony, riot with upheaval…. Monkman occupies the role, most obviously, of the Chosen One, the maiden who must be sacrificed in the ballet and the bardashe figure, who in Caitlin’s racist painting, stands in the place of an anticivilization ethos.15

This artistic re-presentation of a settler-colonial re-presentation of a ceremony we will never have full access to beyond the settler-colonial writings and the racist cartoon shows simulacrum at work as an unfolding as an act of a becoming. There is no original idealized form of self or identity to return to, but there is a past to understand and heal from, a present to learn to live in, and a future still to construct: This is the work of Indigiqueer identity.

Similarly, Indigiqueer postulates how Queer Indigeneity can transform space and time dimensions that the settler colonists tried to atrophy through the identity of berdache and their treatment of all Indigenous peoples but particularly Two-Spirit people:

What does it mean when pimatisowin, the act of living, is immediately shelved into the past tense rather than becoming an ongoing series of unfoldings? This sensation is akin to how it feels to be and embody Two-Spiritedness, in that the moments in which I achieve something are already displaced and ghosted into a past tense that will forever place its possessive apostrophe before my name and being. (202)

Whitehead explores the intersections of queer time16 and Indigenous or NDN (Native Indian) time: For both queer and indigenous peoples, time functions differently, and Indigiqueer is the embodiment of this intersection; it resists being trapped in time or prevented from existing in the present/future. Even now, Indigenous queerness is invisibilized while the trauma of “Indigenous heterosexual cisgendered men” is objectified through stories in the form of testimonials for settler-colonial consumption, where the abuse, often sexual, these men (and women) suffered in residential schools is consumed by a predominately white population as a liberal self-congratulatory act without any real change or self-examination. In this light, Whitehead blames the residential schools for “the current state and livelihoods of Two-Spirit, femme, Indigiqueer and Indigenous women across Turtle Island who are affected profoundly by Indigenous men, masculinities, and heterosexualities” (99), for which after all the “reconciliation” finishes, much of the violence committed is left unexamined and unhealed. Hence, Indigiqueer disrupts and questions these trauma narratives, not as untrue, but as a continuation of a national political tool claiming to reconcile for its past while still propagating the same invisibilization/eradication of queer and female Indigeneity that it always has.

Body as Biotechnology: Science, Technology and Indigenous Spiritualities

Indigenous futurisms and Indigiqueer identities examine queer and Indigenous corporeal experiences in conjunction with Indigenous spiritualities and understandings of nature and bodies while resisting settler-colonial capitalist and patriarchal narratives of science and technology. They disrupt linear conceptualizations of space and time, webbing and weaving organic, spiritual, and scientific elements in the construction of self and other (or the lack thereof) in the “quantum physics of all kinship structures” (14). Whitehead writes of the processes of his body: “My belly is full of quantum physics, elements making love to one another—metals, plate, organs, earth meets water, at the atomic level” (12). For instance, in the book, Whitehead refers to the consumption of maskwa (bear) medicine and meat and the importance it plays in Cree tribal life and spiritualities. This inclusion critiques a colonial version of vegan ethics of meat consumption as cruel and primitive and the racist implications of this view. He critiques the idea of Indigenous peoples as being “savage” for eating wild meat and instead replaces this term with “sauvage” (15). He discusses the process of transmutation of the meat of the body of animal into his own body as a form of dancing or love making, creating new forms of kinship down to the microscopic level, saliva, flora and bacterium where death is a vital part of life. He writes, “Even as we become nothing, meaning that which cannot be named, meaning an embodiment beyond an English understanding, we become all-things, we become kin on a microscopic, hypermetropic, multiplicitous level” (13). In death, the end of the body is a continuance of a spiritual existence. There is no life worth more than another life but life itself is redefined: Death does not hold the same ending as it does in Western culture. Nevertheless, other Indigenous authors have also written about the cultural relationship between veganism and Indigenous lives and traditions.17 Thus, it becomes a vital question for Indigenous futurism and the futures we want to build that do not have clear answers but must be examined through a decolonial lens.

In either case, within Indigenous futurist and Indigiqueer literature, bodies themselves are reconceptualized and the stagnation of time is resisted whether it is through veganism, cyberpunk identities, or other countercultural ideals. For instance, in his book of poetry, Full Metal Indigiqueer,18 Whitehead describes the main character, Zoa as a “Two-Spirit cybernetic trickster” who teaches him how to “re-augment my body: transgressive, punk, Indigiqueer” (36). He postulates these mineral crusted characters as “saviors armed in codex and machinery” (25). Indigenous futurism allows for new hero(in)es to emerge through storytelling and embodied relations with nature and machines while asserting their sovereignty. Even stories that do not exist within the cannon of literature, such as dreams, are explored as a type of virtual reality, and video games provide a provocative space to explore identity. Whitehead writes that as a queer, Indigenous, fat body, role-playing video games provided an “escape” from “being housed in a body—a physical one, but also a cultural, racialized, sexualized and Indigenized one…I re-created myself as an imagined embodiment of pixels: here I was a muscle queen, a femme Orc with a red mohawk” (59-60). Thus, he explains, how in moderation, gaming can help heal trauma as it allows you to become the savior of your own reality and provide spaces for queer romance and decolonial ethics. Thus, he posits that video games, like writing, can be a form “sacred animation” and an important tool in Indigenous futurism (64).

Conclusion: Indigiqueer Futurity and Post-Dystopian Resistance

In conclusion, Indigenous futurism, biostories, and Indigiqueer identities collectively resist certain repetitions of the past, like past apocalypses, and rescue others to transcend and resist the settler-colonial death and destruction that so affects Indigenous and queer lives. They write life back into the texts and expand spaces that allow Indigenous lives to flourish outside of settler dichotomies. They are discovering how to write as sovereign subjects that have lived through past apocalypses and are preparing for the inevitable future ones:

I’m tickled by the irony now, that I was afraid of the apocalypse—for surely we have already survived “finality” and have moved into a post-dystopian future that shimmers on the edge of Canada’s utopian vision of itself in the contemporary. (26)

Likewise, Indigiqueer identity is a way of imagining the future by connecting with the past through these apocalypses: to imagine decolonized, queer futures from within the ruins of climate change, racism, homophobia, transphobia, institutionalized poverty, addiction, diseases, and pandemics. Thus, this apocalypse is framed outside the lens of Christianity. It is not one but many recycled over and over again throughout space and time: apocalypse as plural, “apocalypse as ellipses” (46). Yet each apocalypse is always a rebirth, a new beginning. Just like in life/death, the end and the beginning dance together.

Currently, Indigiqueer and Indigenous futurisms are asking what it means “to be Two-Spirit during apocalypse? What does it mean to search out romance during a pipeline protest?” (46). These questions are simultaneously tragic and beautiful, representing grief and laughter. Writing post-dystopian Indigiqueer biostories empowers people to fight for new futures and offers representation of invisibilized or misrepresented bodies. Finally, the dystopias of the past allow people to dream of Indigenous queer utopias in the future where one can find their center, a place of quietness, peace and healing. Whitehead writes that in Cree: “kiyâm” …means to listen, to avoid making noise—quietness of being asking us to listen fiercely and to respond in a whatever way the body so chooses, but also in a way that is endowed with respect and reciprocity (68).” Thus, whether that quietness can be found through video games, painting, singing, working in the garden, or reading/writing stories, it is part of Indigenous futurisms. It is also the part of Indigiqueer that questions if one is “queer enough to be queer” (68), even if in one’s “queerness,” the body desires peace, healing, even monogamy (without judging those who do not). It changes queerness into a radical act of reciprocity where we use our queerness to figure out how to care for ourselves and each other through the ecological and political shifts, pandemics, grief, trauma, loneliness and isolation. It asks what a sovereign future looks like, ending at the beginning over and over again.

1 Recibido: 18 de noviembre de 2023; aceptado: 13 de mayo de 2024.

2 Escuela de Lenguas Modernas. Correo electrónico: monica.bradley@ucr.ac.cr;

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0755-6389.

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0755-6389.3 Maggie Rogers, “Back in My Body,” Heard It in a Past Life (Los Angeles: Capitol Records, 2019).

4 Joshua Whitehead. Making Love with the Land (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2022). Page numbers from this source will be indicated in parentheses in the text.

5 Hellen Cixious, “The Laugh of the Medusa,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 1, 4 (1976): 875-893. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1086/493306.

6 Luce Irigaray, “This Sex Which Is Not One,” Feminisms (1977): 363–369. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-14428-0_22.

7 Michel Foucault and Robert Hurley, The History of Sexuality (New York: Vintage Books, 1990).

8 Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

9 Jasbir Puar, “The Sexuality of Terrorism,” Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007) 37-79.

10 Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London: Verso, 2004), 20-35.

11 Grace Dillon, ed., Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2012) 11.

12 Joshua Whitehead, Jonny Appleseed (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018).

13 Samuel Lopez, “Sorbon del Zopilote | Bribri.” YouTube, 2020, accessed August 5th, 2024. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JoC20ZMTDQc>.

14 Jack Halberstam, Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020).

15 Halberstam (2020), 110.

16 Jack Halberstam, In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies Subcultural Lives (New York University Press, 2005).

17 Margaret Robinson, “Veganism and Mi’kmaq Legends,” Colonialism and Animality (New York: Routledge, 2020) 107-114. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003013891-4.

18 Joshua Whitehead, Full-metal Indigiqueer: Poems (Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2017).

Escuela de Literatura y Ciencias del Lenguaje,

Universidad Nacional, Campus Omar Dengo

Apartado postal:ado postal: 86-3000. Heredia, Costa Rica

Teléfono: (506) 2562-4051

Correo electrónico: revistaletras@una.cr

Equipo editorial