Revista Letras

EISSN: 2215-4094

Número 57 Enero-junio 2015

Páginas de la 35 a la 75 del documento impreso

Recibido: 22/1/2015 • Aceptado: 12/6/2015

|

Revista Letras EISSN: 2215-4094 Número 57 Enero-junio 2015 Páginas de la 35 a la 75 del documento impreso Recibido: 22/1/2015 • Aceptado: 12/6/2015 |

Design and Development of Authentic Assessment with an Affective, Intellectual, Psychomotor Approach1

(Diseño y desarrollo de evaluación auténtica mediante un enfoque afectivo, intelectual y psicomotor)

Nandayure Valenzuela Arce2

Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica

Gustavo Álvarez Martínez3

Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica

Damaris Cordero Badilla4

Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica

Resumen

En este artículo se plantea que los alcances de la denominada evaluación auténtica se aplican en Costa Rica de forma deficiente. Expone y explica los resultados de un taller dirigido al profesorado de Inglés, y con esa experiencia se ejemplifican vías que potencian la adquisición de conocimiento y desarrollo de habilidades, mediante esa modalidad de evaluación.

Abstract

This article addresses authentic assessment (AA), which is still not applied satisfactorily in Costa Rica. It describes and analyzes the results of a workshop held with English instructors, and based on that experience, examples are given of ways to strengthen knowledge acquisition and skills development, using that type of assessment.

Palabras clave: evaluación auténtica, procesos cognitivos, procesos emocionales, procesos psicomotores

Keywords: authentic assessment, cognitive processes, emotional processes, psychomotor processes

The outreach project for the professional development of English instructors, Desarrollo Profesional para Profesores de Inglés (DEPROMI),5 is an integrated initiative whose dynamics cover several areas: training English teachers—mainly those from rural areas of the country—in different pedagogic domains, formulating research in fields of need in applied linguistics, and developing theories and academic materials derived from these experiences.

For almost two decades, DEPROMI workshops were offered to English teachers in Upala, Nicoya, San Ramón, Pérez Zeledón, Ciudad Neily, Sarapiquí, San Carlos, and others, to enhance these professionals’ pedagogic proficiency. This in turn increases their efficiency in guiding primary school students in the development of English language skills for real world communicative purposes. Some of the criteria used by DEPROMI trainers to select the rural areas in which the workshops on pedagogy could be implemented are the following: the request of authorities from the Ministry of Public Education (MEP) or other educational institutions; the teachers’ need for formal, well-grounded opportunities for professional growth in their communities; and these educators’ willingness to participate in DEPROMI training.

In 2012, one of the professors interested in offering a DEPROMI workshop was Patricia López,6 who drew attention to knowledge and skill limitations that educators in San Carlos had on using assessment as an efficient mechanism to evaluate their pupils’ progress in English. She explained that this situation had become one of the stumbling blocks for a number of young learners in San Carlos to be able to use their foreign language as a means of communication. She also said that although the teachers from San Carlos had limited access to solid training on pedagogic areas, they were willing to learn. In response, DEPROMI trainers accepted to offer a workshop on authentic assessment (AA) to those educators in November 2013.

O’Malley and Valdez use the term authentic assessment “to describe the multiple forms of assessment that reflect student learning, achievement, motivation, and attitudes on instructionally-relevant classroom activities.”7 This is a type of appraisal that must be aligned to the methodologies that are grounded on communicative principles for language learning. Without knowledge on AA and competence in its appropriate application, teachers are less familiar with students’ day-to-day weak and strong outcomes during English classes, and are therefore, unable to make informed decisions for instructional planning.

Due to the relevance of AA, DEPROMI trainers knew that the workshop should be prepared to go beyond attaining surface objectives; it had to pursue teachers’ long-lasting professional development, derived from solid training objectives that could lead these educators to adjust knowledge and tools to their own teaching needs and to those of their pupils. As stated by El Estado de la Educación (2005), efficient educators should “design and implement diverse learning evaluation strategies and processes based on predetermined criteria,”8 and this knowledge basis and competences on evaluation ought to match [teachers’] capacity to ‘select, elaborate, and utilize didactic materials pertinent to their context.’”9 In other words, the DEPROMI workshop on AA had to be designed for the development of teachers’ critical thinking and creativity, while encouraging their commitment to use AA beyond the training experience by designing and implementing on-going evaluation appropriate for their primary school students’ needs.

Consequently, an-eight hour workshop on AA was given on November 27th, 2013, at CTEC in Santa Clara, San Carlos. A week later, TEC emphasized the successful partnership between this college and Universidad Nacional, which led to the efficient training of San Carlos English teachers in the workshop entitled Principles on Assessment to Trigger Quality Learning.10

Upon the completion of this experience, the data were analyzed following practices and theories from the systematization experience methodology (SE), which Jara defines as “a new modality of production of knowledge,”11 in which theory emerges from the encounter, views, and contributions of the protagonists participating in the academic experience.12 Therefore, this article is the result of the analysis made by DEPROMI trainers and the contributions of the teachers who participated in the workshop.

The results of the workshop are organized in three sections; the first analyzes the design process of the training on AA, including a description of the teaching approach, learning strategies, didactic materials, evaluation tools, and others; the second describes a step-by-step rationale of the learning/assessment activities, as well as the trainers’ and participants’ actions and reactions during the implementation of the activities; and the third presents the evaluation of the workshop from the perspective of the participating teachers, along with reflections of DEPROMI trainers.

Design Process

General and Specific Objectives

The general objective of the AA training was to share theoretical and experiential knowledge on authentic on-going evaluation with English teachers of San Carlos, to enable them to appraise their primary school students’ development of English skills more accurately.

The first specific objective was to diagnose these English teachers’ background knowledge in AA, to learn exactly how much they knew about the evaluation theories and strategies that they were going to approach during the workshop. The second was to increase their sensitivity toward the learning and AA needs of their primary school students. The third specific objective was for these instructors to become aware of the effectiveness of incorporating informal, semi-formal, and formal AA in a communicative English lesson, as designed by DEPROMI for primary school students following pre-, while-, and post-learning stages. The fourth was to have the educators analyze what AA implies and help them connect unfamiliar knowledge with that acquired through their professional experiences. The fifth specific objective was to have them design an analytic rating scale jointly, in addition to a holistic rubric, to implement formal assessment more objectively in their primary school classes. Finally, the sixth objective was to motivate the teachers to incorporate, in their own English classes, what they had learned about AA.

The content on AA included in this workshop deals with the following themes: theory on foreign language communicative teaching and learning, with emphasis on the Challenge Approach; the theory of process and product of AA; different types of authentic assessment (informal, semi-formal and formal); strategies for the integration of structure, content, and theory through a communicative model lesson; tools to design pedagogical materials; a variety of efficient teaching, learning, and assessment strategies; and theory and guidelines to design analytic and holistic rubrics for AA.

The Challenge Approach: Pedagogical Foundations of the Workshop

We chose the Challenge Approach13 (CHA) as the pedagogic basis for the development of the workshop since it offers many possibilities to digest input meaningfully. This approach is eclectic perspective used by DEPROMI for foreign language teaching and learning. It blends communicative principles from non-traditional approaches with related communicative principles from DEPROMI. The CHA integrates elements from the Natural Approach, Communicative Language Teaching, Cooperative Language Learning, Content-Based Instruction, and Task-Based Instruction.

The above communicative principles prioritize natural learning processes and propose learning strategies that can be adapted to different contexts and learners of different ages. According to Krashen and Terrel, these principles include the following concepts: a) in the natural order of acquisition, comprehension precedes production; b) input has to be offered in the foreign language and it must be scaffolded to make it comprehensible; c) using the learner’s background as a point of departure facilitates the acquisition of linguistic input; d) the continual use of the foreign language is the vehicle to develop communicative and linguistic competence; and e) the learner must be exposed to real communicative situations to create the need and motivation for interaction using the foreign language.14

In the case of the Challenge Approach, the amalgamated communicative principles are a) to set up the challenge (i + 2)15 competing against oneself, to achieve the superior language goal; b) to stimulate implicit learning, leading the student to discover and make connections among different types of knowledge, and following this implied process, incorporate explicit learning (for those who require it) to consolidate knowledge; c) activate and develop the learners’ creative thinking that has to be worked into attitudes and actions leading to meaningful learning; and d) develop nonverbal ability to create efficient contexts and strategies for stimulating interaction that can ease the development of communicative competence.

We have developed this approach based on the experience of teaching our own classes in primary school and at the university level, as well as while offering workshops as trainers in DEPROMI. Over the past thirteen years, we have designed this teaching and learning approach in which we consider as a corollary task teaching meaningfully, but also to learn comprehensively ourselves. That is, when we prepare classes, workshops, seminars, or any other academic activity, we formulate action plans in an evocative way, so that we can help students, participants, and/or audiences to understand and learn more efficiently. The strategy works in both directions because, as we create strategies, activities, materials, and others for the intended academic activity, we expand our own knowledge on the given context, thus increasing cognitive and emotional connections that we had built up previously.

The Challenge Principle

The challenge itself is an intricate emotional, intellectual, and psychomotor test for trainers and trainees because it implies hard work to accomplish a higher goal; it entails making a decision to accept the challenge, and it is more likely to be accepted when that challenge creates a desire to arouse or stimulate, especially when presented with difficulties. For us, as trainers, the challenge is to be able to cope with the analytical, critical, and creative work that we must be committed to carrying out, in order to offer comprehensive learning experiences that will be memorable for the English teachers. We have to investigate, analyze, and design multiple strategies, activities, and materials in synchrony with the singular needs of the participants of the workshop.

To have participants achieve linguistic and/or pedagogical development, we design learning challenges to trigger their motivation, effort, and perseverance, as well as to stimulate their multiple intelligences. Accordingly, all tasks planned for the workshop are designed from the perspective of the English teachers’ needs and particular characteristics. Thus, we explore different ways to present the pedagogical contents and stimulate the educators’ learning styles. Bailey, Curtis and Nunan state that professional development occurs, and “results in better teaching and learning…if there is some sense of mutuality or reciprocity...” during the training experience, in which educators’ contribution to build up knowledge is considered.16 For this reason, we also anticipate challenging strategies for teachers to be able to appreciate the value of their own professional expertise by having them share it with us and their colleagues the connections that they are able to make between theory and their teaching practice; this is an approach that enables teachers to build on their personal and professional pride.

Finally, it is clear that a challenge is a personal decision, so each individual is responsible for accepting or rejecting the proposed challenge. This depends on internal and external factors that can have a positive or negative effect on the participants’ attitudes, but no matter how influenced one can be by these variables, a positive attitude and a resolute personality can help overcome obstacles that may appear. We promote this affirmative attitude and model it through the professional design of the workshop and our encouraging behavior during the training process.

The Creativity Principle

In the CHA, creativity is the communicative principle that keeps trainers and trainees innovating. We consider the cognitive and emotional impact of teaching and learning strategies, activities, and materials, and this leads us to be open to changes and to create. Although we do follow patterns for teaching that experts have proven to be efficient in a given context, we do so only after having piloted those principles and having made necessary adaptations according to the needs of DEPROMI’s target population. Creativity is based on from emotional and cognitive flexibility which enables us to detach ourselves from the teaching and learning practices that we believe are the best (but might not be), to be open to adapt and innovate whenever necessary. We proceed this way because every group of participants is different. Individuals live under different cultural, social, economic and educational realities, but there are principles from teaching approaches that do not take this into account.

Hence, we are constantly creating new paths for teaching depending on 1) the characteristics of the English teachers that we are going to interact with; 2) the essence of the community in which the participants work (including culture, education, geography, politics, economy, etc.); and 3) the contents that we intend to approach in the training. The diverse scenarios that we deal with require us to use our creativity. Likewise, in the workshops we stimulate the participants’ development of creative skills since they too should be constantly designing and adapting theories, methods, strategies, materials and evaluation, on behalf of their students’ efficient development of the foreign language. To fulfill this objective, we use two main strategies: 1) the workshop itself must be an example of creativity portrayed through all its academic dynamics; and 2) the activities must require the participants to create, adapt, modify and even discard strategies, materials or others during the process.

The Nonverbal Communication (NVC) Principle

This is another relevant communicative principle of the CHA that not all professionals consider paramount to the development of English proficiency and to the success of academic activities such as workshops. Samovar, Porter and Jain (in Damen) claim that NVC involves “all those stimuli within a communication setting, both humanly generated and environmentally generated, with the exception of verbal stimuli, that have potential message value for the sender or receiver.”17 Many people do not realize that NVC is essential. However, Birdwhistell has shown that 65% of all our communication is nonverbal, Bantom (1995) considers that 90% of our emotions are expressed nonverbally, and Mehrabian goes further to state that 93% of the meaning is attained through NVC (in McEntee).18 In DEPROMI workshops, we try to make sure that we use all four types of NVC properly: body language, object language, environmental language, and paralanguage.19 To use positive NVC, we analyze the theories that we will be approaching in the training and practice the implementation of all teaching and learning strategies to be incorporated. NVC can also serve to carry out AA by including, as appraisal strategies, “physical demonstrations and pictorial products expressing academic concepts or content knowledge without speech or writing.”20

Having expertise in NVC helps build professional confidence, which in turn manifests itself in positive NVC. This is relevant because participants need to trust and respect trainees as professionals who can lead them to expand their knowledge and develop skills. As a result, teachers will be willing to take up the challenge to learn; openness to the trainer can create openness to the subject matter as well. We also use NVC to show our respect and appreciation for trainees. They need to feel that we consider them good professionals who signed up to the workshop to enhance their knowledge and who are willing to share their valuable professional experiences with colleagues and with us. Through these NVC strategies, we intend to have participants notice the relevance of this resource and use it to instill openness in their own primary school students; this process hopefully will encourage them to take up their own challenges in their English classes.

Assessment Tools

We established different types of assessment in the planning of the workshop. For example, we began with a diagnostic assessment21 to appraise the participants’ prior knowledge on AA, testing, and evaluation. In every activity that we implement, we also evaluate the progress of the participants’ understanding, in terms of their advance in academic matters and also on how they feel about the teaching/leaning activities carried out in the workshop. The informal, semi-formal and formal assessment processes implemented provide us with data that are useful to decide whether we should continue developing the activities or offer more explanation and examples on those aspects that are still not clearly understood by a few, some, or all of the participants. Pursuant to the communicative way in which we teach in the workshop, we also designed analytic and holistic rubrics. Furthermore, we designed a self-assessment rubric (see appendix 2),22 to offer trainees the possibility of experiencing the benefits of self-assessment procedures, and have them reflect on whether they believed that they had—or had not—learned more about AA.

Sources and Materials

Some of the pedagogical sources and materials used in the project are innovative and others are original. This includes pictures, stories, videos, and other sources taken from internet, books, etc., but the innovation lies in how we contextualize,23 modify, personalize, organize, and add guidelines for their appropriate use. According to Gardner, variety in teaching (including strategies, sources, materials, and others), helps people cope with the plurality of intelligences of human beings,24 since each talent—emphasize Richards and Rodgers—enriches the others, supporting language learning.25 In consequence, we use a plethora of sources and materials which constitute routes that ease comprehension from diverse angles. We create materials for the English teachers’ instruction process and also for primary school children’s language learning development. All material is designed, adapted or modified seeking high standards of quality, since they must be appealing to increase interest and motivation. Moreover, these resources must be related to objectives of the language class to serve its purposes; hence, we pilot them before, during, and after the implementation of workshops, constantly improving them.

Framework of the Workshop on AA

Tables 1-3 provide a brief overview of the teaching and learning dynamics of the training on AA. General and specific objectives of the workshop have been omitted in the subsequent planning since they are stated at the beginning of this paper; however, cognitive, affective, and psychomotor aims are included in the framework below, as an example of the many purposes that can be pursued in academic activities. In addition, the descriptions of objectives and learning activities are written from the perspective of the teachers (using the pronoun “we”) to emphasize one of the principles of DEPROMI workshops: Professional development must be apprentice-centered. It is also important to clarify that the rationale of each academic activity is the basis of the analysis of its implementation in section 2. Table 1 describes the entry tasks designed to prepare the English teachers for the subsequent experiences.

Table 1. Structure of workshop planning on authentic assessment for the pre-learning stage

|

CONDITION |

OBJECTIVES |

ACTIVITY |

|

-Quotation: “A teacher is a person who knows…” |

-Bridge ideas in the quotation with self-teaching experiences -Demonstrate critical thinking when verbalizing ideas |

We read the quote, reflect on its meaning, and relate it to our own professional practice. Then, we verbalize our ideas with colleagues, illustrating and justifying them with examples, anecdotes, explanations. |

|

-Power point presentation -Interaction of trainers and trainees during break times |

-Develop trust in the trainers’ professional experience and expertise -Appreciate the respect and deference that the trainers show towards us at the professional level |

We listen to indirect introductions of DEPROMI trainees’ professional credentials on evaluation. We also read this information and look at photographs of the trainers’ childhood in a PowerPoint presentation. We mingle with trainers during break to share conversations on personal and academic issues. |

|

-Motivation activity (song): “So You Want to Be a Teacher” -Worksheet with lyrics of the song |

-Evoke diverse roles that we take on in the classes that we teach -Compare and contrast the roles described in the song with the ones that we have taken on in our professional practice |

We use our background knowledge to list the diverse roles that we perform in an English class. We listen to the song as we watch the video that illustrates its message. We sing the song aided by its lyrics. We express our analysis of the song’s message, connecting it with our teaching experience. |

|

-Diagnosis survey on assessment |

-Provide information of our AA background knowledge |

We fill in a diagnostic survey to inform the trainers about our knowledge on AA. |

|

Facilitators: N. Valenzuela, G. Álvarez, D. Cordero Target population: teachers from San Carlos Content: Authentic Assessment Goal: trigger joint building of knowledge Workshop planned by Nandayure Valenzuela (2013) |

||

Table 2 includes the learning dynamics used to enhance knowledge and develop skills in AA during the workshop.

Table 2. Structure of workshop planning on authentic assessment for the while-learning stage

|

CONDITION |

OBJECTIVES |

ACTIVITY |

|

-Poor lesson -Stories written in foreign languages |

-Become aware of the need to prepare efficient learning and assessment classes |

In groups, we are asked to decipher (with no verbal or written guidance) the message of a story written in French, Portuguese, Italian, etc. We have to retell the story in English in front of the class. We analyze the task. |

|

-Model lesson for primary school students -AA strategies and rubrics |

-Become aware of effective cognitive, emotional, and psychomotor processes of primary school students |

We take on the role of primary school students to participate in a model lesson on farm animals. We experience all the learning and assessment tasks proposed, being guided and assessed at every step of the lesson. |

|

-Worksheets with rhetoric questions |

-Decipher the theory underlying the model lesson |

Aided by questions on a worksheet, we work in groups analyzing the learning and assessment tasks of the model lesson, to elicit its theoretical grounding. We present our findings to the whole class. |

|

-Power point presentation including clue theoretical grounding on AA |

-Consolidate understanding of theory rooted in the model lesson |

We analyze the theoretical grounding of the model lesson while listening to the trainers providing explicit explanations of the issue. We participate by asking questions and enriching the discussion with examples from our own teaching experiences. |

|

-Analytic and holistic rating scales |

-Design and evaluate analytic and holistic rating scales that are suitable for our teaching context |

At the laboratory, we study the analytic and holistic rating scales shown and explained by the trainers. In groups, we create our own scales using the computers and aided by written instructions. We assess our own scales. |

Table 3 lists the post-instructional tasks that include two types of assessment, as used during the workshop.

Table 3. Structure of workshop planning on authentic assessment for the post-learning stage

|

CONDITION |

OBJECTIVES |

ACTIVITY |

|

-Closing activity: song on farm animals |

-Recall cognitive, emotional, and psychomotor objectives of workshop |

We move around performing and singing the farm animal song used in the model lesson. |

|

-Formal self-assessment for teachers’ |

-Become aware of my integral evolution in this AA workshop |

We use the self-assessment form in Spanish or English version handed out by the trainers. We read the criteria, reflect on them and appraise our progress on AA. |

|

-Formal assessment of the workshop and trainers’ performances |

-Provide feedback to the trainers on evolution of the workshop |

We reflect on the quality of the design and implementation of the workshop on AA and the trainers’ performance, based on the criteria stated in the corresponding assessment form. |

Rationale of the Workshop and Results of Its Implementation

Opening Dynamics

On behalf of the participants’ long-term learning, DEPROMI workshops were designed considering the synchronic activation of cognitive, emotional, and psychomotor intelligences; this motivation is achieved from the very beginning by using an inquiry opener. Kindsvatter, Wilen, and Ishler explain that “the opening or entry of a lesson…can have an important influence on how much students learn from a lesson” (in Richards and Rodgers).26 Therefore, we began the workshop in San Carlos with an activity that would raise the participants’ interest and make them aware that their contribution throughout the training was considered vital to joint knowledge construction and skill development. We decided to activate critical thinking by having the English teachers read the following quotation: “A teacher is a person who knows all the answers but only if she asks a question” (Wong and Tripe).27 This source, we expected, could motivate the educators to relate the ideas in the quotation to their pre-existing experiences in the classroom; then they would share their thoughts and justify them.

When this activity was implemented, the teachers read the quotation aloud and some read it again silently. They reflected on it for a while, and then verbalized their ideas. Although initially the group was shy about participating, enthusiasm grew over time as volunteers stated their ideas. At the end, there was a great variety of interpretations of the quotation and a plethora of examples and opinions derived from the connections each teacher had established.

Creating Receptiveness towards Professional Development

Another introductory stratagem was devised to foster positive attitudes of trustfulness, empathy, and willingness towards us and the workshop, for it would prepare the teachers to be open to analyzing and evaluating the theories that we would be presenting during the training experience. Teachers’ reticence to take in new content and teaching approaches is common since they tend to protect their own belief system. Shavelson and Stern suggest “that what teachers do is governed by what they think, and that teachers’ theories and beliefs serve as a filter through which a host of instructional judgments and decisions are made (in Richards).28

To ease the way to receptiveness, we had to earn the participants’ respect and trust from the beginning; therefore, we devised mechanisms that could answer their undisclosed questions about the trainers. We anticipated that some of these inquiries could be the following: Are these trainers well prepared to teach the contents of the workshop? Do they have experience in the content areas that will be approached? Have they considered the educational context in which we (teachers) have to implement the AA theories? Will they value and use our professional expertise and experience during the training?

To deal appropriately with the participants’ inner questioning, we introduced ourselves using a PowerPoint presentation with information that provides evidence of our proficiency in evaluation, our main publications, and experience teaching English in primary school. The purpose was for the teachers to confirm that we are accredited professionals with the expertise required to present the complex content on AA that would be dealt with during the training. Consequently, we designed two specific strategies that would portray our professional merits, but highlighting our belief in reciprocal learning (we learn from them, they learn from us, we learn together).

The first action consisted of sharing pertinent, concise data of each trainer’s professional credentials, using a PowerPoint presentation. However, saying who you are professionally can be perceived by the trainees as arrogance, given the fact that in Costa Rican culture it is not considered appropriate for trainers to highlight their professional accreditation directly. Thus, we believed it would be positive to illustrate the information with photographs of each of us when we were children (2 to 4 years old), as a means of portraying tenderness, humility, and desire to learn. The implicit message then would be that, although we have competences that enable us to offer a workshop on AA, we are also like children who still have much to learn and are open to build knowledge from them, the teachers.

We also included a parallel strategy to prevent the teachers from believing that our intention was to set a professional distance between them and ourselves. We thought of carrying out the introductions indirectly; that is, the trainers would each present the qualifications of a colleague rather than highlighting their own. We practiced these introductions previously, making sure that we were using modest, friendly verbal and non-verbal communication strategies.

A second strategy was planned to take advantage of breaks to socialize with the educators. Each of us would approach a different group of teachers during coffee breaks and lunch to make conversation, being sure that we would elude the temptation of leading it. We intended to increase our opportunities to learn more about the participants and interact with them as colleagues.

During the implementation of the first plan of action, the teachers smiled when they saw each of our photographs at the top of our professional credentials, and they listened attentively to the indirect introductions. Their body language did not reveal negative attitudes towards us, but we were still not sure that we had succeeded in gaining their acceptance; however, this openness was confirmed through their evident commitment while carrying out the cognitive, affective, and psychomotor tasks during the training, and it also was apparent in their comments when they evaluated the workshop at the end.

The above strategy was reinforced by our interaction with the teachers during breaks—the second strategy—for each of us was received warmly by every group of educators that we joined. The teachers gradually became more comfortable with our presence, and they risked talking about some personal and academic situations that they were facing at that time. That is, we shortened the distance between the teachers and ourselves.

Motivation Activity

Motivation is essential to learning, so we designed a stimulating activity to activate mental and emotional processes to awaken the participants’ interest and readiness to learn. We used the song “So You Want to Be a Teacher,”29 whose lyrics describe and video support—in a happy, fun way—an array of responsibilities that teachers have been assigned, and many other duties that they freely and lovingly take on. The song and video also reveal educators’ values, hard work beyond duty, and the multiple roles that they have in the classes that they teach: teachers, nurses, psychologists, fund raisers, and many others. The song is graceful, melodic, and rich in lexicon.

After listening to the song, the teachers compared and contrasted the information provided in the song with their own values, efforts, and roles in their professional practice, so we formulated insightful questions that could stimulate and guide them to do so. Thus, the teachers’ critical thinking would be prompted through cognitive tasks that could assist them in noticing, evocating, comparing, contrasting, evaluating, etc.

The results of this activity went beyond our expectations. The song and video accomplished the objective of cheering up the teachers, for it was comparable to an anthem of educators’ work. The participants focused on the song and sang along. Their body language revealed their agreement with the praising of teachers’ commitment and professional vocation emphasized in the lyrics. The teachers were interested in learning the vocabulary used in this song, which they were not familiar with, so they kept on asking us the meaning of several words. Guided by questions, the teachers expressed their analysis of the message of the song and added more, remarking on additional ones that they had taken on over time in their professional practice.

Survey to Diagnose Teachers’ Knowledge on AA

To document how much the teachers knew about AA at the beginning of the workshop, we designed a survey30 to compare and contrast these data later with appraisal of the educators’ knowledge and skill development progress on AA throughout the workshop and at the end. The survey consisted of several open and closed questions through which we hoped to learn whether the teachers had taken any courses on assessment, and the depth of the knowledge from informal or formal instructional training or program focused on this topic.

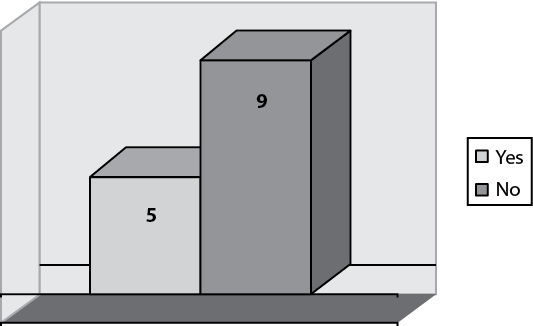

The analysis of the data showed that of the 14 fourteen teachers attending the DEPROMI workshop, only 5 had received some training on generalities of evaluation, as portrayed in figure 1.

Answers to the question “Have you received formal training on assessment?”

Fig. 1. Graph illustrating English teachers’ answers to question #7 on the diagnostic survey, aimed to assess their knowledge on AA.

These educators’ training on evaluation was weak, especially in assessment. The survey showed that 90% could state the difference between assessment and testing. However, appraisal dynamics of the training uncovered the fact that the teachers did not have well-grounded knowledge on AA; for example, they could not distinguish among different types of on-going evaluation (informal, semi-formal, and formal), they did not know how to use data collected through assessment to improve the teaching/learning process, nor were they skillful on designing assessment instruments such as rating scales.

Putting Teachers in Their Pupils’ Shoes

Before approaching theory on assessment by implicit and explicit teaching strategies, it was critical to appeal to the teachers’ sensitivity and responsibility towards their students, having them realize that they would be much better professionals if they increased their knowledge on assessment and developed skills to design appraisal activities and assessment instruments such as rating scales. Consequently, we designed an activity for the teachers to experience being in a class with inadequate teaching and assessment procedures would be absent, but the teachers would not know that this ineffective class was designed on purpose.

The trainees were invited to take on the role of primary school students, while the trainers acted as their teachers. The trainees were asked to form small groups, but no guidance was provided. We handed out stories written in languages that these educators would probably have little or no command of Chinese, Portuguese, Italian, and French. The trainees were asked to read the stories and be prepared to re-tell them in front of the class.

From the beginning of this activity, the teachers’ body language revealed their astonishment, insecurity, frustration, confusion and fear, for they had no idea that the poor class was an experiment. We just proceeded with the task asking them to do one thing or another, but omitting efficient teaching procedures such as providing clear verbal and written instructions, giving examples of what they had to do, and using positive NVC. The educators kept looking at each other for help and some were murmuring. They were unable to understand the stories written in Chinese, Portuguese, Italian or French, and felt embarrassed because they could not retell them in front of the class when they were asked to do so. Afterward, we asked them what had been wrong with the class, why it was inadequate, and how they had felt during the process.

The educators pointed out the lack of guidelines and other organizational strategies to orient the task, the absence of scaffolding procedures, and the use of negative NVC on the part of the trainers. They described the array of adverse emotions that this inappropriate class had fostered in them. In response to our inquiries, they stated their ideas on how the learning and assessment outcomes could be improved. Having the participants take the role of the primary school students in this activity enabled them to put themselves in the shoes of young learners who often experience weak classes that fail to motivate and aid them in their learning process. Therefore, the teachers were able to evaluate the need of assessment from this perspective.

Model Lesson for Primary School Students

The next step was centered on exposing the participants to implicit learning of the complexities of pedagogic theories through the implementation of the core activity of the workshop: a communicative model lesson on farm animals designed by the trainers, in which all theoretical components of the Challenge Approach were embedded, with a particular focus on the relationship between teaching the foreign language to children and assessing these students’ learning processes.

Again the teachers had to take the role of primary school students, and the trainers the role of primary teachers. This integrated model lesson was intended to provide the participants with learning experiences that stimulate emotions, activate mental processes, and engage them in psychomotor efforts, all of which enable them to achieve three objectives: 1) identify and begin to take in the theory that had been extrapolated from the model lesson, 2) distinguish the strategies used by the trainers to translate pedagogical theory into teaching and learning practices, and 3) experience the effect of the communicative principles of the CHA on children’s development of English skills.

Step by step, we carried out the lesson using hands-on activities that were organized hierarchically, harmonizing intellectual processes with logical learning stages (pre-/while-/post- + language ability; for example, pre-listening, while-listening, post-listening). Meaningful learning was mediated by colorful, appealing and efficient pedagogical materials. Some of them—such as flashcards—were designed by the trainers, others were taken from the internet and adapted, and we also used realia. We employed a variety of sources including songs, animated images of farm animals projected in PowerPoint presentations, videos, and more.

We had previously designed worksheets to guide and encourage the practice of language functions (such as exercises for young learners to work on listening and speaking), more elaborate worksheets intended for semiformal assessment, and rating scales for formal assessment of the children’s progress. We had designed learning activities that serve both purposes: to trigger learning and to assess the progress of learning. Thus we exemplified how teachers can simplify the process of AA in their lessons.

On the whole, we sought to have participants look at teaching, learning, and assessing a foreign language from the standpoint of children, so that this experience would provide them a different view of children’s emotional, cognitive, and psychomotor needs—a within perspective—and to have them become aware that they (teachers) owe their young learners the most substantial and enjoyable learning and assessment experiences possible.

The implementation of this model lesson was one of the activities that the participants the most. They played the role of primary school students. They were willing to engage in the multiple learning activities programmed: they sang, played, carried out hands-on activities, and moved around the class to work in pairs and in small groups. They showed their delight by performing in English at all times, proving their readiness to act out, being open to work with their peers, laughing, etc.

This model lesson enabled the teachers to understand how children feel when the English class has been well planned, based on effective communicative principles, and the teacher directs the class with positive attitudes staying in the background to have the students be at the center of the stage in the learning tasks. These conclusions were drawn from observations of the participants’ behavior during the implementation of the lesson (informal assessment), and from the teachers’ analysis of the theory underlying the model lesson (semiformal assessment).

Eliciting and Bridging Subsumed Theory

Upon the completion of the model lesson, another stage of implicit learning of theory was to be addressed. The participants had to switch back from the role of young learners to their normal identity as teachers, to engage in an analytical task in which they would be guided to elicit the theory underlying the learning experience of the model lesson. The objective of this reflective effort was to have participants analyze, interpret, and evaluate theory and practice that is subsumed in the model lesson from two perspectives: 1) their vision as children while assuming that role during the exemplified learning experience, and 2) their parallel perceptions as English teachers during the same class. The young learners’ point of view provides teachers a frame of reference centered on the cognitive, emotional, and psychomotor processes that children experience in well-guided, fun, and meaningful learning process. The perspective as teachers enables them to evaluate the model lesson from a conscious, mature, professional viewpoint. The analysis based on this dual outlook is provided to activate the participants’ reflection using the routes provided in table 4.

Table 4. Brief inventory of intellectual, affective, and psychomotor processes

|

Routes of Analysis 1) Identify the theory implicit in the different teaching, learning, and assessment elements of the model lesson. 2) Distinguish and break down the multiple communicative principles of the Challenge Approach underlying the lesson. 3) Compare and contrast the new input to pre-existing knowledge. 4) Connect theory to pre-existing knowledge and experiences. 5) Find patterns and organize them. 6) Evaluate the effectiveness of the implementation of theory. 7) Accommodate the digested knowledge. 8) Verbalize the analysis using strong arguments to support opinions. |

This task was set up to be carried out in small groups, using a worksheet that specified the type of learning task, cognitive objectives, time allotted, and instructions. It was complemented by a creative prompt-section to guide the participants’ routes of analysis, and in which they also had space to organize and write down their ideas. The outcomes of that reflection had to be shared by each group in front of the class, to generate multiple ways of unveiling the communicative principles embedded in the model lesson and to promote an awareness of the strategies used by the trainers to lead to the practical use the theoretical grounding on pedagogy, evidenced in the design and implementation of an English model lesson for primary school students.

When the educators carried out this implicit analysis, they explored and discussed different elements of their experience during the model lesson and linked the dynamics of the lesson, their professional experience in teaching, and their pre-existing theoretical knowledge. At this point, we had not yet disclosed the communicative learning and assessment principles of the CHA, but through analysis they came across most of them. Each group shared their conclusions with the rest of the class and nurtured their theoretical arguments with explanations and examples of their professional practice.

Explicit Approach to Theory

Theories, in general, seem complex and the use of specialized technical language in English adds to the difficulties that many English teachers have to decode them; however, through the implicit learning tasks used previously,31 the participants had already been exposed twice to the communicative principles of the CHA, so in a third encounter, participants were ready to address pedagogic theory and its specialized language from a straightforward perspective.

We thus designed an explicit analysis task to have the participants expand their knowledge on the CHA pedagogical theory. We had summarized key aspects of theoretical grounding for teaching, learning, and assessment, and had designed a PowerPoint presentation to support our explanations. The data were illustrated through an array of pictures, instead of crowded texts; and only very specific key information was incorporated as text, giving priority to words and phrases over complete sentences. The goal was to have participants connect the images and text illustrated in the presentation to our explanations of theoretical foundations, so that they could attain a better comprehension of the topics under scrutiny. Moreover, we asked the participants to add their examples and anecdotes to encourage them to use specialized terminology meaningfully and consolidate their knowledge by linking theory with their professional experience.

We decided to keep theoretical explanations as short as possible. Twenty minutes was the limit unless the teachers’ participation caused us to extend the time assigned; however, we always did our best to keep explicit theoretical explanations short. Experience has taught us that people get bored very soon with direct approaches to theory; that is one of the reasons why comprehension of the theory on assessment was worked out through multiple channels and at different moments during the workshop. On the whole, the expertise of the trainers must be applied during the design of this explicit teaching strategy for it has to be mediated in such a way that the analysis of theoretical grounding can become palatable, captivating, and meaningful.

The above strategy for the use of PowerPoint presentations is based on our observations as members of the audience in many congresses, seminars, workshops and others. We have learned that PowerPoint presentations with too many slides have three negative effects during an academic activity: 1) participants do not pay attention to verbal explanations since they are focused on reading the texts in the presentation, 2) participants tend to lose the thread of ideas posed on a slide when they have not completed reading its content and the slide is withdrawn to present a new one, and 3) participants are unable to benefit from the verbal explanation of theory because, at the time they switch from reading to listening, the trainers might be discussing a topic different from the one participants were focused on.

The employment of this explicit strategy to theory was successful. It provided teachers access to a more complete understanding of the intrinsic theory of the model lesson. We offered an explicit explanation of the communicative principles of the CHA by scaffolding the complexity of clue concepts with the support of the PowerPoint presentation, in which images prevailed over text. We also used examples from our own professional practice to help participants make meaningful connections between theory and practice. We assessed the comprehension of the topics through observation of the participants’ body language (informal assessment) and noticed that they were listening to the trainers’ explanations and paying attention to the slides. The teachers showed interest and curiosity asking questions, making comments and giving their own examples related to the theory being explained (semiformal assessment).

Collaborative Design of Rating Scales

To have the participants build skills that could help them extrapolate theory into teaching/learning assessment activities, we designed professional psychomotor-based tasks in which the participants would have to work collaboratively to create analytic and holistic rating scales for assessing their primary school students’ oral production.

Using hands-on tasks in the workshops is necessary for several reasons. First, designing learning activities grounded on the theory studied enables participants to interpret and test the knowledge acquired during the training from a practical perspective. Second, participants use communicative principles to create learning/assessment products that correspond to their students’ learning needs and educational context in which the learning will take place. Third, hands-on activities are a way of assessing the participants’ understanding of knowledge, and of giving trainers the opportunity to detect weaknesses and assist the teachers. And fourth, participants learn different avenues to use communicative learning and assessment principles in a practical way by analyzing the pedagogical products designed by their colleagues.

Another strategy to enhance the participants’ learning on assessment consisted of having them evaluate the model lesson, the rating scales used during the training session, and our performances as trainers. The teachers had to base their appraisal on the rating scales that we designed for each case (see appendix 1),32 keeping in mind that the core objective of that assessment task is to provide the teachers with another approach for digesting theory on assessment; this is, by taking the role of raters. The new scope would offer these educators’ multiple opportunities to discover the underlying assessment theory anchored in the design of the rating scales and the practicability of their implementation to enhance objectivity in the evaluation of outcomes. Our hope was that this assessment task would also encourage the participants to design and implement assessment instruments to evaluate the progress of their students.

From a psychological point of view, we designed learning activities with the participants as the main characters of all performances. They were meant to be the ones to take the center of the stage using examples from their professional experience to clarify or illustrate theory; or asking questions that could be answered by colleagues and, only if no one else could, by the trainers. This strategy was intended to enable participants to feel confident and respected; our message to them would be that, although we were the ones guiding the dynamics of the workshop, we knew that they were professionals with experience who could nurture one another—and us—with their knowledge.

Up to this point, the teachers had approached theory from three perspectives: an experiential approach (involved in the model lesson), the implicit analysis of theory (derivation of theory through analysis of the model lesson in small groups), and the explicit analysis (straightforward teaching of theory carried out by trainers with contributions from trainees), so now their assimilation of theory was solid enough to enable them to generate pedagogical products based on it.

Since the focus of the workshop was on assessment, we asked the participants to design an analytic rating scale to appraise the oral production of primary school students. We all moved to the laboratory to have the teachers design the rating scales using computers. Once there, we described the different types of rating scales (analytic and holistic) and the main elements defining them such as headings, objectives, criteria, and narrative and numerical rubrics. We divided the class into small groups and assigned each team a specific task: 1) writing the description of an assigned criterion (communication, fluency, content, pronunciation, grammar, etc.), 2) calibrating this criterion according to the command of English that their students in first or second grade have, 3) setting the weight for each component while keeping homogeneity in the distance among numerical levels, 4) assigning narrative rubrics to the corresponding numerical rubrics, and 5) preparing themselves to explain and justify their design of a section of the rating scale to the rest of the class, based on theoretical grounding on AA.

The design task, as expected, was carried out with difficulty. The affective filter of the participants increased when they were confronted with the responsibility of using theoretical knowledge on assessment to design a practical evaluation tool. Most professionals are able to understand theory and to talk about it, yet not use it creatively. This procedure turned out to be the greatest challenge of the training (i + 2), because designing rubrics implies bringing to a conscious level pre-existing knowledge and theory on assessment received during the training, synchronizing it with cognitive and psychomotor processes, activating skills for creativity, and adjusting theory to the particular learning and assessment needs of primary school students.

In anticipation of the teachers’ probable increasing levels of anxiety, frustration and confusion due to this hands-on challenge, we had designed posters with analytic and holistic rating scales that could serve as a point of departure for them to create their own assessment instruments. Other analytic and holistic scales were presented in a PowerPoint presentation to provide more detail about the parameters for assigning weight to different components of language.

The participants were comfortable with the theoretical information on rating scales provided until they had to do their part. We provided each group with a digital file containing a framework to use for the description of a language component. The teachers were surprised by the difficulty of the task. They had an intuitive knowledge on what fluency, grammar, communication, vocabulary, pronunciation and other elements of language meant; however, the educators found them difficult to describe. Descriptions of criteria are one of the most challenging tasks when creating a valid rating scale, not only because the challenge implies activating an array of intelligences and skills at once, but also because most teachers lack knowledge about technical definitions of these components. We were busy going from group to group answering the participants’ questions and giving them emotional support to finish the task.

The teachers’ # body language mirrored their uncertainty: furrowed brows, wide open eyes, sweaty foreheads, arms embracing heads, and paralanguage such as “ay, uf,” and other sounds denoting stress. There were also direct verbal complaints such as “But…what do I have to write here?”, or “How do you describe pronunciation?” We did not take those expressions as an attack because we had expected them. Instead, we were patient and guided the teachers by asking them questions that would lead them to build on the technical description of the language components. For example, we asked them: “When you assess the pronunciation of a second-grade student, what aspects of pronunciation do you expect him/her to have mastered?”

Finally, the teachers carried out this hands-on activity successfully and presented their results to the whole group. Each team projected their part of the rating scale and justified the description of the given criterion, calibrated the vocabulary to suit their students’ command of English, justified the choices for having given more or less weight to the language component assigned, and offered a conclusion of the learning gained through this analytic and experiential task dealing with the design of a particular section of an analytic rating scale.

We integrated the participants’ criteria in a single document to show how the parts of their rating scale built up a well-calibrated analytic rating scale to assess second grade students’ oral production. The teachers were exhausted but satisfied with their work. This task was the formal assessment used to test the participants’ assimilation of theoretical and practical contents of the workshop.

Closing Activity

To conclude the workshop, we designed an activity that includes art, because of its potential to relax and motivate the participants. We almost always use songs as to close training programs. At this point, the teachers were very tired, but a well-chosen piece of music had the power to relax listeners. In addition, the song served to summarize the topics covered during the training, and provided one final meaningful message to encourage participants to apply, in their workplace, what they had learned.

Evaluation of the Workshop

Teachers’ Appraisal through Self-Assessment

The self-assessment instrument (see appendix 2)33 was given to the teachers to “help them assess fundamental beliefs and assumptions about learning, learners, and teaching, as well as differences between their perceptions of practice and those held by students in their classroom.”34 This self-assessment instrument has two additional purposes: 1) to gather evidence of the learning gained by the participants on diverse aspects of assessment, and 2) to encourage the teachers to commit themselves to implementing efficient assessment practices in their classes in primary school.

The analysis of the data provided by these assessment tools revealed that all English teachers agreed that, upon completing the workshop, it was “totally true” that they were able to differentiate between assessment and testing processes; single out some of the core features of authentic assessment required to appraise the development of English language skills; identify informal, semi-formal, and formal assessment procedures; acknowledge that assessment techniques must be planned and integrated in every English session; became aware that assessing their students in all language skills is essential to ground much better and speed more effectively their language development; and realized that they must assess their own lesson plans and assessment tools as a means of achieving higher standards for professional development.

Another section of the self-assessment form triggers reflection on rating scales. One hundred percent of the educators manifested that, upon completion of the workshop, they had been able to select the main language components required to assess their students’ oral production in English; write basic descriptions (criteria) of language components for assessing their students’ oral performances in English; calibrate rubrics in a rating scale by setting different numerical weights (values) in language components that harmonize with their students’ particular English level and which fit the nature of the task to be executed by them; adjust rubrics in a rating scale by setting different narrative/qualitative weights (values) in language components that line up with their students’ particular English level and that fit the nature of the task to be performed by them; and analyze and evaluate a rating scale appropriately using a reliable checklist-guide designed for that purpose.

The last section of the self-assessment rating scale inquires on the teachers’ motivation to use AA beyond the workshop experience. Ninety percent of them stated that it was “totally true” and ten percent that it was “mostly true” that this workshop had encouraged them to commit themselves to including AA procedures in their English classes in primary school, and that they felt stimulated to continue expanding their knowledge on AA.

Positive Effect of the Workshop

At the beginning of the training, the teachers had a general knowledge of AA theory and practice. Although they did apply informal assessment procedures in their lessons such as classroom observations, most of them did not document and systematize the information garnered through informal, semi-formal and formal assessment mechanisms to improve teaching or learning practices. In addition, they were not familiar with the technical lexicon of the different components of scales, nor with their function for measuring observable behaviors reflecting the learners’ evolution or involution during the lesson; instead, teachers were accustomed to using the evaluation instruments designed by MEP or downloaded from internet. Consequently, at first it was difficult for them to internalize theory on AA and engage in the design of analytic and holistic rating scales.

However, the progress of these educators was documented during the workshop through experiential, implicit, and explicit evaluation mechanisms, and triangulation was attained via hands-on tasks. The teachers went into further detail on AA and its intrinsic connection with the learning process. They were able to understand the complexities of assessment through the different implicit and explicit learning experiences in which they were involved. They built on knowledge gradually, and this was evident in their successful design of rating scales. The teachers also realized that every group of students has its singularities regarding learning styles, and that for this reason, evaluation instruments must be created in harmony with their pupils’ specific emotional, cognitive, and psychomotor distinctiveness.

Finally, through an evaluation form,35 the teachers rated the workshop as excellent in all aspects, such as organization, methodology, effectiveness of didactic materials and techniques. Concerning the trainers’ performance, the teachers also emphasized the professional, creative, and humanistic behavior with which they had conducted the academic experience. As trainers, we rate the work and commitment of these teachers from San Carlos as outstanding and give them credit for their professional contributions based on their professional experiences in primary school milieus.

Appendix 1: Checklist to Assess an Analytic Rating Scale

DEPROMI trainers designed an analytic rating scale to assess second-grade students’ oral description of farm animals. The English teachers—participants in the DEPROMI workshop—assessed the validity of the rating scale, using the checklist provided.

Objectives

General Instructions

Assessment Checklist

|

CRITERIA |

Degree of Achievement |

||

|

Yes |

Partly |

No |

|

|

FORMAT of the Assessment Rating Scale The layout of the rating scale is professional and suitable for the intended primary school students. To accomplish this, the trainers: |

|||

|

1. centered the text on the page; i.e., top, bottom, left and right margins are well calibrated |

|||

|

2. chose legible typeface style and font size to enable students, parents and educational authorities to read smoothly and comprehensibly the data included in the analytic scale |

|||

|

3. followed an appropriate layout for organizing tables, diagrams, pictures, and other elements using suitable organization |

|||

|

4. set adequate spacing between lines, so that the assessment form appears uncluttered |

|||

|

5. numbered all pages to maintain readers well oriented on the right sequence of the analytic rating scale |

|||

|

HEADING of the Assessment Rating Scale To accomplish this, the trainers have included all required data in the rating scale heading as described below: |

|||

|

1. name of the educational institution |

|||

|

2. school term and year |

|||

|

3. type of assessment (analytic, holistic, hybrid) |

|||

|

4. language skill(s) or sub-skill(s) being assessed: reading, writing, listening, speaking, culture, grammar or vocabulary |

|||

|

5. total points and grade |

|||

|

6. level in school |

|||

|

7. name of the rater or teacher administering the assessment task; |

|||

|

8. date when the assessment was/will be administered; |

|||

|

9. time allotted for administering the assessment, |

|||

|

10. spaces to include the number of points and grade obtained by the student; |

|||

|

11. a line to write the student’s name; |

|||

|

12. a line for the student’s parents to sign the assessment form, if required. |

|||

|

OBJECTIVE(S) of the Assessment Rating Scale To accomplish this, the trainers included an objective(s) in the following way: |

|||

|

1. They wrote an objective(s) that establishes: “a) the behavior: specific action or performance expected of the student; b) the condition: circumstance(s) under which the behavior is to be demonstrated; and c) the criterion: degree or level to which the behavior must be demonstrated to be acceptable” (taken from: Claremont Educational Resources, 1985). |

|||

|

2. The objective(s) is written clearly, precisely, and concisely. |

|||

|

INSTRUCTIONS of the Assessment Rating Scale To accomplish this, the trainers have: |

|||

|

1. included a set of steps that orient on how to use the assessment rating scale |

|||

|

2. organized instructions numerically or alphabetically in a proper way |

|||

|

3. used appropriate action verbs to introduce each set of instructions |

|||

|

4. written these guiding-steps in a complete and clear manner. |

|||

|

CRITERIA of the Assessment Rating Scale To accomplish this, the trainers have: |

|||

|

1. selected at least three components (pronunciation, grammar, communication, etc.) suitable to evaluate the students’ description of farm animals |

|||

|

2. described each criterion considering the students’ realistic command of the language |

|||

|

3. described each criterion considering the content on farm animals that the students will have to describe |

|||

|

QUALITATIVE RUBRICS AND NUMERICAL RUBRICS To accomplish this, the trainers have: |

|||

|

1. used an appropriate quality hierarchy in each criterion, by establishing at least five levels of oral achievement through adjectives such as: outstanding, very good, average, weak, very poor, etc. |

|||

|

2. established rubrics (scale, numbers) in each criterion that are useful to score –in a summative manner– how well the students carry out the farm animal description task |

|||

|

3. made sure that the adjective scale and the numerical scale in each criterion are analogous |

|||

|

4. calibrated the rubrics (scales) in each criterion by setting the same numerical distance between the five levels of performance |

|||

|

5. placed different weights among the rubrics (scales) of each criterion to give more relevance to those oral performance components that the students can handle better, in accordance with their stage of language development |

|||

|

CREDITS The trainers have followed copyright laws by giving credit to the authors of intellectual works such as illustrations, rating scale, and others. |

|||

Appendix 2: Participant’s Self-Assessment

Knowledge and Skills on Assessment

Objective: I will carry out an honest introspection to become aware of the degree of advance that I have been able to achieve on English teaching/learning assessment theories and practice, at the level of primary school education.

|

CRITERIA Upon completion of this workshop I have been able to… |

|

||||||||||

|

About generalities on assessment |

|||||||||||

|

a. differentiate between assessment and testing processes |

1□ 2□ 3□ 4□ 5□ |

||||||||||

|

b. single out some of the core features of authentic assessment required to appraise the development of English language skills |

1□ 2□ 3□ 4□ 5□ |

||||||||||

|

c. identify informal, semi-formal and formal assessment procedures |

1□ 2□ 3□ 4□ 5□ |

||||||||||

|

d. admit assessment procedures must be planned and integrated in every English session |

1□ 2□ 3□ 4□ 5□ |

||||||||||

|

e. acknowledge that assessing my students in all language skills is essential to ground much better and speed more effectively their language development |

1□ 2□ 3□ 4□ 5□ |

||||||||||

|

f. become aware of the need to assess my own lesson plans and assessment tools as a means to achieve higher standards of professional development |

1□ 2□ 3□ 4□ 5□ |

||||||||||

|

About rating scales |

|||||||||||

|

a. select the main language components that are required to assess my students’ oral production in English |

1□ 2□ 3□ 4□ 5□ |

||||||||||

|

b. write basic descriptions (criteria) of language components for assessing my students’ oral performances in English |

1□ 2□ 3□ 4□ 5□ |

||||||||||

|

c. calibrate rubrics in a rating scale by setting different numerical weights (values) in language components that harmonize with students’ particular English level and fit the nature of the task to be executed by them |

1□ 2□ 3□ 4□ 5□ |

||||||||||

|

d. adjust rubrics in a rating scale by setting different narrative/qualitative weights (values) in language components that harmonize with students’ particular English level and fit the nature of the task to be completed |

1□ 2□ 3□ 4□ 5□ |

||||||||||

|

e. analyze and evaluate a rating scale appropriately using a reliable checklist-guide designed for that purpose |

1□ 2□ 3□ 4□ 5□ |

||||||||||

|

About implementation of assessment |

|||||||||||

|

a. feel committed to including assessment procedures in the English classes that I teach in primary school |

1□ 2□ 3□ 4□ 5□ |

||||||||||

|

b. feel motivated to continue expanding my knowledge on authentic assessment |

1□ 2□ 3□ 4□ 5□ |

||||||||||

1 Recibido: 22 de enero de 2015; aceptado: 12 de junio de 2015.

2 Escuela de Literatura y Ciencias del Lenguaje. Correo electrónico: Nandayureva@gmail.com

3 Escuela de Literatura y Ciencias del Lenguaje. Correo electrónico: lgtavo@yahoo.com

4 Escuela de Literatura y Ciencias del Lenguaje. Correo electrónico: jodaro.damaris@gmail.com

5 This project was carried out as part of the in-service elementary teacher-training program (Programa de Capacitación para Maestros de Inglés (PROCAMI), Escuela de Literatura y Ciencias del Lenguaje (ELCL), Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica, Proyecto integrado: extensión, docencia, investigación, Universidad Nacional; código 0265-11.

6 Patricia López is a professor of the Escuela de Ciencias y Letras, who works with the Centro de Transferencia Tecnológica y Educación Continua (CTEC), of the Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica (TEC). We wish to thank López for her valuable contributions in establishing the necessary agreement between UNA and TEC, which enabled DEPROMI to offer the workshop on assessment to San Carlos English teachers.

7 Michael O’Malley and Lorraine Valdez. Authentic Assessment for English Language Learners: Practical Approaches for Teachers (New York: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1996) 4.

8 Programa Estado de La Nación en Desarrollo Humano Sostenible Estado de la Educación Costarricense / Programa Estado de la Nación. Aporte especial. Capítulo #3. La Educación Superior y la Generación de Conocimiento (Consejo Nacional de Rectores, San José, Costa Rica. 2005, 138).

9 Programa, 138.

10 Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica, “TEC y UNA se Aliaron para Capacitar a Docentes en Inglés.” Comunicado de Prensa (CTEC sede Santa Clara, San Carlos, Costa Rica, Oficina de Comunicación y Mercadeo, 3 de diciembre de 2013).

11 Oscar Jara, La sistematización de experiencias: práctica y teoría para oros mundos posibles (San José, Costa Rica: Centro de Estudios y Publicaciones Alforja, 2012, 41).

12 Jara, 41.

13 Gustavo Álvarez, Nuria Villalobos and Nandayure Valenzuela, “The Challenge Approach: An Innovative Teaching and Learning Pathway,” Revista de Lenguas Modernas 11 (2009): 363-382.

14 Jack Richards and Theodore Rodgers, Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. 2nd ed. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

15 In Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition (New York: Prentice Hall International, 1995, 20-21), Stephen Krashen suggests that learners move from current competence “i” to the following level (that is, i + 1). They accomplish this by understanding first the new input that is “a little beyond” their acquired linguistic abilities. However, the CHA emphasizes that learners can be challenged to move from their current competence to a much higher level (i + 2), when taking advantage of the pedagogical strategies of this eclectic approach.

16 Kathleen Bailey, Andy Curtis and David Nunan, Pursuing Professional Development: The Self as Source (Boston, MA: Newbury House, 2001, 5).

17 Louise Damen, Culture Learning: The Fifth Dimension in the Language Classroom (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1987, 168).

18 Eileen McEmtee, Comunicación intercultural: bases para la comunicación efectiva en el mundo actual (Mexico: McGraw-Hill, 1998) 384.

19 Gustavo Álvarez, Nandayure Valenzuela y Floria Sáenz, “Non-verbal Communication: An Icon for Effective Classroom Management” (II Congreso Internacional de Lingüística Aplicada (CILAP II). Escuela de Literatura y Ciencias del Lenguaje, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad Nacional, Heredia, Costa Rica, 2009) 4.

20 Jo-Ellen Tannenbaum, “Practical Ideas on Alternative Assessment for ESL Students” (ERIC Digest. 1996. 13 Jan. 2015. <http://ericae.net/db/edo/ED395500.htm>).

21 Nandayure Valenzuela, Gustavo Álvarez and Damaris Cordero. Diagnosis Survey on AA (DEPROMI Workshop on Authentic Assessment, held in San Carlos, Alajuela, Costa Rica, 2013, unpublished).

22 Nandayure Valenzuela, Gustavo Álvarez and Damaris Cordero, “Teachers’ Self-Assessment Rating Scale Self-Assessment Form.” (DEPROMI Workshop on Authentic Assessment, held in San Carlos, Alajuela, Costa Rica, 2013, unpublished).

23 Materials are created according to the particular educational, social, and cultural needs of the target group.

24 Howard Gardner, Multiple Intelligences: The Theory in Practice (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1993) 32-33.

25 Jack Richards and Theodore Rodgers, Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. 2nd ed. (Cambridge, UK: CUP, 2001) 116-117.

26 Richards and Rodgers, 114.

27 Harry Wong and Rosemary Tripe Wong, The First Days of School: How to Be an Effective Teacher (Sunnyvale, CA: Wong Publications, 1991) 36.

28 Jack Richards, Beyond Training, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, UK: CUP, 2000) 66.

29 Garapan Elementary School, Recruitment Ad/Slideshow (Saipan, MP), “So You Want to Be a Teacher” (YouTube. 15 Jan. 2008. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Kj8Y7aWhh8>).

30 Valenzuela et al., Diagnosis Survey.

31 First, the experience of the model lesson; and second, the implicit analysis of the experience through a dual perspective.

32 Nandayure Valenzuela, Gustavo Álvarez and Damaris Cordero, Checklist to Assess a Rating Scale (DEPROMI Workshop on Authentic Assessment, held in San Carlos, Alajuela, Costa Rica, 2013, unpublished).

33 Valenzuela et al., “Teachers’ Self-Assessment Rating Scale”

34 Barbara McCombs, Self-Assessment and Reflection: Tools for Promoting Teacher Changes toward Learner-Centered Practices. (1997. 13 Dec. 2014. <http://bul.sagepub.com/content/81/587/1.short>, 1).

35 Gustavo Álvarez, Nandayure Valenzuela and Damaris Cordero, Evaluation of Workshop on AA and DEPROMI Trainers’ Performance. Analytic Rating Scale (DEPROMI Workshop on Authentic Assessment, San Carlos, Alajuela, Costa Rica, 2013).