ISSN: 1659-455X • e-ISSN: 1659-407X

Vol. 16 (1), enero-junio 2024

Recepción 23 abril 2024 • Corregido 7 junio 2024 • Aceptado 10 junio 2024

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15359/revmar.16-1.2

|

New records of Minuca zacae (Brachyura: Ocypodidae) in the Gulfs of Montijo and Parita, Panama Nuevos registros de Minuca zacae (Brachyura: Ocypodidae) en los golfos Montijo y Parita, Panamá |

ABSTRACT

We present the first report of the Lesser Mexican Fiddler Crab, Minuca zacae Crane, 1941, in Panama. The identity of crabs from the Gulfs of Montijo and Parita was confirmed by presenting a broad frontal region, oblique orbits, and a palm without an oblique tuberculate ridge. This report fills a distribution gap between Costa Rica and Colombia and updates this species range from Altata Bay, northern Mexico, to Málaga Bay, Colombia.

Keywords: Fiddler crabs, distribution range, morphology, chela, Eastern Pacific.

RESUMEN

Presentamos el primer reporte del cangrejo violinista mexicano menor, Minuca zacae Crane, 1941, en Panamá. La identidad de los cangrejos de los golfos Montijo y Parita fue confirmada por mostrar la frente ancha, órbitas oblicuas y palma sin cresta tuberculada oblicua. Este reporte cierra un vacío distribucional entre Costa Rica y Colombia, con lo cual se actualiza el rango de la especie desde bahía de Altata, norte de México, hasta bahía de Málaga, Colombia.

Palabras claves: cangrejos violinistas, intervalo de distribución, morfología, quela, Pacífico Oriental.

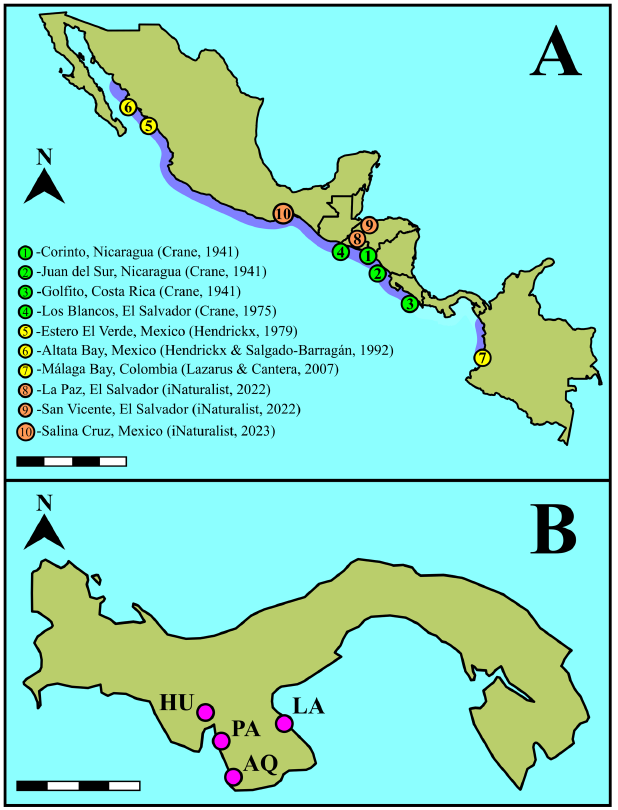

Fiddler crabs are commonly distributed in sandy mudflats, mangroves, and wetlands in tropical and subtropical regions (Crane, 1975; Rosenberg, 2014). Out of the 107 extant species listed on the website “Fiddler Crabs” (http://www.fiddlercrab.info/index.html) (Rosenberg, 2014), 29 are found on the Pacific coast of Panama (Crane, 1975; Shih et al. 2015; Shih et al. 2016; Lombardo, 2022). Some species may exhibit cryptic characteristics (e.g., small size and blending colors), making their presence easily overlooked (Crane, 1941; Hendrickx, 1979). Even brightly colored species, such as Minuca osa Landstorfer & Schubart, 2010, may remain unnoticed; for example, it was reported in Panama only twelve years after its initial discovery in Costa Rica (Lombardo, 2022). Given this context, we hypothesized the presence of other unreported fiddler crabs in Panama. One potential case is that of the Lesser Mexican Fiddler Crab, Minuca zacae Crane, 1941 which was initially reported in Corinto and San Juan del Sur in Nicaragua and Golfito in Costa Rica (Crane, 1941; Crane, 1975). Since Crane (1941), reports for M. zacae in the eastern Pacific region had settled its range from Mexico to Costa Rica (Crane, 1975; Hendrickx, 1979, Hendrickx & Salgado-Barragán, 1992; Hendrickx, 1995; Rosenberg, 2002; Landstorfer & Schubart, 2010; Rosenberg, 2014; 2020). However, reports from Bahía de Málaga in Colombia by Lazarus & Cantera, 2007 accounted for the presence of M. zacae at four locations, suggesting a distribution gap in Panama (Fig. 1A). Filling the gaps in fiddler crab distribution is important as they impact ecosystem functioning through their burrowing and bioturbation activities (Smith et al. 2009; Mokhtari et al. 2016; Booth et al. 2019; El-Hacen et al. 2019). Therefore, the objective of this study was to confirm the identity of fiddler crabs found in the Montijo and Parita Gulfs exhibiting M. zacae characteristics, in order to update its distribution range.

Fig. 1. Distribution of Minuca zacae Crane, 1941, in the Eastern Tropical Pacific. A. Distribution range (Rosenberg, 2014; http://www.fiddlercrab.info/index.html) highlighted in purple. B. Sampling sites in the Gulf of Montijo (PA = Ponuga, HU = Las Huacas, AQ = Arenas de Quebro) and the Gulf of Parita (LA = Los Aromos). Scale bars: A, 1 000 km; B, 140 km.

Fig. 1. Distribución de Minuca zacae Crane, 1941, en el Pacífico Tropical Oriental. A. Rango de distribución (Rosenberg, 2014; http://www.fiddlercrab.info/index.html) en púrpura. B. Sitios de muestreo en el golfo de Montijo (PA = Ponuga, HU = Las Huacas, AQ = Arenas de Quebro) y golfo de Parita (LA = Los Aromos). Escala: A, 1 000 km; B, 140 km.

Our survey focused on four sites, three of which were located in the Gulf of Montijo: Ponuga (07º 51ʼ 44.769ʼʼ N, 081º 01ʼ 01.559ʼʼ W) was visited in June 2022 and October 2023; Las Huacas (07° 53ʼ 03.584ʼʼ N, 081° 08ʼ 39.767ʼʼ W) was sampled in January 2024; and Arenas de Quebro (07° 20ʼ 01.022ʼʼ N, 080° 53ʼ 03.281ʼʼ W) in February 2024. The fourth site was located in the Gulf of Parita, Los Aromos (07º 55ʼ 57.649ʼʼ N, 80º 19ʼ 51.173ʼʼ W) and was surveyed in April 2024 (Fig. 1B). Specimens were observed directly in the field, hand-caught (N = 10) and placed in 75 ml plastic containers. In the laboratory, crabs were rinsed with tap water and euthanized in a freezer for five minutes to facilitate analysis and photography. The carapace width-front width ratio and chela height and length were measured (precision 0.01 mm) for scaling. Carapace width was compared with biometrics reported in the literature. Morphological features of interest were photographed using a stereoscope (SZ2-ILST) equipped with a camera (EP50) and processed with EPview software (Olympus, Japan). Species identification was conducted using specialized literature (Crane, 1941; Bott, 1954; Crane, 1975; Landstorfer & Schubart, 2010; Rosenberg, 2014; Shih et al. 2015, 2016; Rosenberg, 2020).

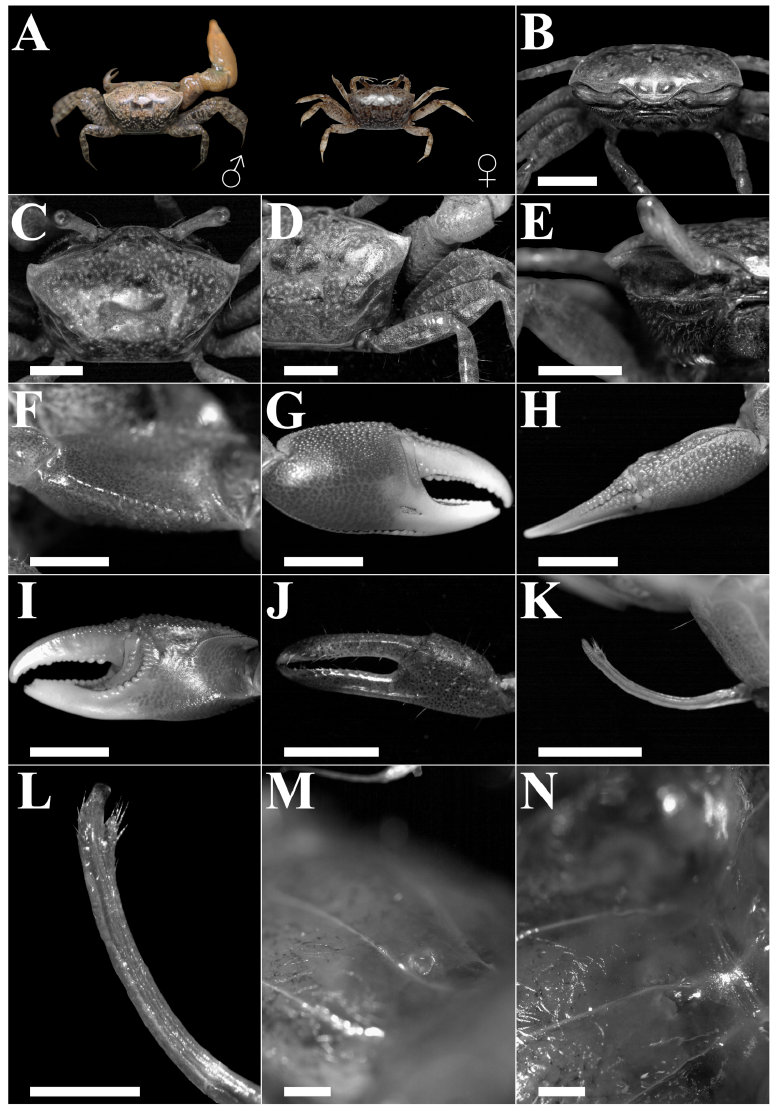

Among the ten Minuca zacae specimens collected, eight were male and two were female, none ovigerous. The average carapace width was 10.17 ± 1.02 mm. These specimens were found on mudflats near mangrove vegetation, alongside Minuca herradurensis Bott, 1954, and Minuca galapagensis Rathbun, 1902. The size range of our sampled M. zacae suggests they are, at first glance, similar in size to those in previous reports but smaller than their sympatric species (Table 1). Males and females (Fig. 2A) exhibited traits fitting the description of Minuca zacae, including: broad frontal region with two small protuberances on the upper side (Fig. 2B-C), and an average carapace width-front width ratio of 4.6:1 (Fig. 2B); pits on the carapace surface with an indistinct pattern; no pubescence on the carapace besides pile traces in the grooves of the H-like depression of the cardiac-mesogastric region (Fig. 2C); dorsally, the anterolateral angles are rectilinear and do not project beyond the front (Fig. 2A-C); ocular orbits significantly, but not excessively, oblique (Fig. 2B); anterolateral margins distinct, short, slightly convex, and posteriorly angled; dorsolateral margins slightly converging and align with the lower edge of the cardiac-mesogastric region (Fig. 2C); two posterolateral striae, with the upper longer than the lower, the latter barely noticeable in small specimens (Fig. 2D); in frontal view, the upper portion of the pterigostomial region (adjacent floor of orbit) with a concave ridge with minute crenations, this region and the suborbital region not densely setose, crenations increase moderately in size externally (Fig. 2E); abdominal segments 3-6 partially fused; meri of ambulatories slender, with dorsal edges almost straight (Fig. 2A, D); walking legs naked, except for small patches on the dorsal margin of the carpus and propodus; merus of major chela with two rows of small serrations on the ventral margin, serrations changing distally to small tubercles, particularly in the anterior row (Fig. 2F); on average (n = 8), the width of the manus of major chela contained 2.1 times within its length; pollex and dactyl slightly longer than palm, lower part of the outer manus with a row of small, bead-like supramarginal tubercles near the base, tubercles larger and spaced out towards the distal half, ending at the pollex base; a clear shallow, triangular depression at the base of the pollex just above the beaded margin (Fig. 2G), with less than 0.5 of the outer upper manus covered by large tubercles, extending to the dorsal margin of the dactylus diminishing distally (Fig. 2H); palm lacking an oblique tuberculate ridge, central surface smooth, beaded inner edge of the dorsal margin curving downward around the carpal cavity, without connection between the carpal cavity and upper palm faint, depression displaying weak tuberculation, two ridges associated with the dactyl base, proximal not diverging from distal (Fig. 2I), dactyl curving downward beyond the pollex as typical for the genus; inner row of tubercles in pollex prehensile edge obsolescent to absent, tubercles in the outer row weak, median row prominent, near the tip a large tubercle close to the outer edge, followed by two smaller tubercles, dactyl prehensile edge featuring rounded, enlarged tubercles in proximal 0.5, spaced equally apart (Fig. 2G, I); small chela gape narrower than dactyl width, pollex and dactyl with weak serrations on the distal third with scare setae (Fig. 2J), fingertips of the minor chela slightly curving inward, spoon-like shaped; gonopod flanges broad of similar width and length, slightly concave, inner process translucent, narrow, tapering distally, pore opening posteriorly, with flanges seemingly fused in front of channel, thumb setose, fully formed, inserted much lower than flanges and extending below their base (Fig. 2K-L); female gonopore crescent-shape, with thickened lip, not unevenly raised, without tubercle (Fig. 2M-N).

Table 1. Carapace width reported for Minuca zacae Crane, 1941, specimens from the Gulfs of Montijo and Parita. Values provided in previous reports from the Eastern Tropical Pacific are indicated for M. zacae, M. osa, M. galapagensis, and M. herradurensis

Tabla 1. Ancho del caparazón en Minuca zacae Crane, 1941, de los golfos Montijo y Parita. Valores en informes previos del Pacífico Tropical Oriental se indican para M. zacae, M. osa, M. galapagensis y M. herradurensis

|

Species |

Carapace width (Mean ± SD) |

Mean difference |

Location |

References |

|

M. zacae |

10.17 ± 1.02 |

1.06 |

Gulfs of Montijo and Parita, Panama |

This study |

|

9.11 ± 2.55 |

Altata bay, Mexico to Golfito, Costa Rica |

Crane (1975); Hendrickx & Salgado-Barragán (1992); Rosenberg (2002) |

||

|

M. osa |

16.22 ± 3.70 |

-6.05 |

Golfo Dulce, Costa Rica |

|

|

21.44 ± 2.96 |

-11.27 |

Gulf of Montijo, Panama |

||

|

M. galapagensis |

20.11 ± 2.00 |

-9.94 |

Rodman, Panama |

|

|

M. herradurensis |

16.49 ± 5.86 |

-6.32 |

Diablo Creek, Port of Rodman, and Taboguilla Island, Panama |

Fig. 2. Diagnostic characteristics of Minuca zacae Crane, 1941, from the Gulfs of Montijo and Parita, Panama. A: Male, CW 12.1 mm, and female, CW 8.9 mm (color of live specimens). B: Frontal view and region and orbits. C: Dorsal view of carapace, anterolateral angles and margins. D: Carapace striae. E: Suborbital region. F: Merus of major chela. G: Outer view of major chela. H: Dorsal view of outer upper manus and dactyl of major chela. I: Major chela, inner surface. J: Minor chela, outer surface. K-L: Male right gonopod (anterolateral). M-N: Female gonopore. Scale bar: B, C, D, E, K, 3 mm; F, G, H, J, 5 mm; L, 1 mm; M, N, 2 mm.

Fig. 2. Características diagnósticas de Minuca zacae Crane 1941, del golfo de Montijo y Parita, Panamá. A: Macho, CW 12.1 mm y hembra, 8.9 mm (color en vida). B: Vista frontal, ceja y órbitas. C: Vista dorsal del caparazón, ángulos anterolaterales y márgenes. D: Estrías del caparazón. E: Región suborbital. F: Mero de quela mayor. G: Vista externa de quela mayor. H: Vista dorsal del manus y dáctilo de quela mayor. I: Superficie interna de quela mayor. J: Quela menor, superficie externa. K-L: Gonopodio derecho del macho (anterolateral). M-N: Gonoporo de la hembra. Escala: B, C, D, E, K, 3 mm; F, G, H, J, 5 mm; L, 1 mm; M, N, 2 mm.

Compared to its sympatric species, M. zacae is smaller, a feature also reported by Crane (1975) and Rosenberg (2023). This overlap implies adults can be mistaken for juveniles of M. herradurensis and M. galapagensis (Crane, 1975; Hendrickx, 1979; Rosenberg, 2023). Minuca zacae differs from these two species as follows: it possesses more oblique orbits, thick brow; the oblique tuberculate ridge on the palm is absent; fingers are longer than the palm; although leptochelous, the major chela is stouter than in other species of Minuca. Merus of ambulatory legs is slender, which is also noticeable in females (Crane, 1975). The gonopod in male M. zacae lacks a distinct anterior flange, as in M. galapagensis and M. herradurensis. In M. herradurensis, the anterior flange always extends beyond the posterior. Moreover, the inner process of the gonopods in M. zacae is relatively subtle, unlike in other species of Minuca (Crane, 1975). Minuca osa is another species whose juveniles may be mistaken for M. zacae due to similar carapace color and spot pattern (Landstorfer & Schubart, 2010). However, a notable difference is the presence of a prominent oblique tuberculate ridge on the palm of M. osa (Landstorfer & Schubart, 2010; Lombardo, 2022), absent in M. zacae. Based on their morphology, specimens collected in Montijo and Parita belong to M. zacae. This report bridges the M. zacae distribution gap between Costa Rica (Rosenberg, 2020) and Colombia (Lazarus & Cantera, 2007), covering a range from Bahía Altata, northern Mexico (Hendrickx & Salgado-Barragán, 1992) to Bahía de Málaga, southern Colombia (Lazarus & Cantera, 2007).

We would like to thank Carl Thurman and Hsi-Te Shih for appraising early specimen images, the anonymous reviewers for their manuscript feedback, and Virgilio Villalaz for his logistical support.

Booth, J. M., Fusi, M., Marasco, R., Mbobo, T. & Daffonchio, D. (2019). Fiddler crab bioturbation determines consistent changes in bacterial communities across contrasting environmental conditions. Sci. Rep., 9(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40315-0

Bott, R. (1954). Dekapoden (Crustacea) aus El Salvador. 1. Winkerkrabben (Uca). Senck. Biol., 36(3/4), 155-180. https://decapoda.nhm.org/pdfs/26967/26967-001.pdf

Crane, J. (1941). Eastern Pacific expeditions of the New York Zoological Society. XXVI. Crabs of the genus Uca from the west coast of Central America. Zool. Sci. Contrib. N. Y. Zool. Soc., 26(19), 145-208. https://doi.org/10.5962/p.184677

Crane, J. (1975). Fiddler crabs of the world: Ocypodidae: Genus Uca. (1st ed.). EE. UU. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400867936

El-Hacen, E. H. M., Bouma, T. J., Oomen, P., Piersma, T. & Olff, H. (2019). Large-scale ecosystem engineering by flamingos and fiddler crabs on West-African intertidal flats promote joint food availability. Oikos, 128(5), 753-764. https://doi.org/10.1111/OIK.05261

Hendrickx, M. E. (1979). Range extensions of fiddler crabs (Decapoda, Brachyura, Ocypodidae) on the Pacific coast of America. Crustaceana, 36(2), 200-202. https://doi.org/10.1163/156854079X00447

Hendrickx, M. E. (1995). Checklist of brachyuran crabs (Crustacea: Decapoda) from the eastern tropical Pacific. Bull. Inst. Roy. Sci. Nat. Belgique, 65, 125–150.

Hendrickx, M. E. & Salgado-Barragán, J. (1992). New records of two species of brachyuran crabs (Decapoda: Brachyura) from tropical coastal lagoons, Pacific coast of Mexico. Rev. Biol. Trop., 40(1), 149-150. https://revistas.ucr.ac.cr/index.php/rbt/article/view/31767

Landstorfer, R. B. & Schubart, C. D. (2010). A phylogeny of Pacific fiddler crabs of the subgenus Minuca (Crustacea, Brachyura, Ocypodidae: Uca) with the description of a new species from a tropical gulf in Pacific Costa Rica. J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res., 48(3), 213-218. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0469.2009.00554.x

Lazarus, J. F. & Cantera, J. R. (2007). Crustáceos (Crustacea: Sessilia, Stomatopoda, Isopoda, Amphipoda, Decapoda) de Bahía Málaga, Valle del Cauca (Pacífico colombiano). Biota Colomb., 8(2), 221-239. https://revistas.humboldt.org.co/index.php/biota/article/view/192

Lombardo, R. C. (2022). First record of the Fiddler Crab, Minuca osa from the Eastern Montijo Gulf, Panama. Rev. Mar. Cost., 14(2), 27-35. https://doi.org/10.15359/revmar.14-2.2

Mokhtari, M., Ghaffar, M. A., Usup, G. & Cob, Z. C. (2016). Effects of fiddler crab burrows on sediment properties in the mangrove mudflats of Sungai Sepang, Malaysia. Biology (Basel), 5(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/BIOLOGY5010007

Rathbun, M. J. (1902). Papers from the Hopkins Stanford Galapagos expedition, 1898-1899. VIII. Brachyura and Macrura. J. Wash. Acad. Sci., 4, 275-292. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24526068

Rosenberg, M. S. (2002). Fiddler crab claw shape variation: a geometric morphometric analysis across the genus Uca (Crustacea: Brachyura: Ocypodidae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. Lond., 75(2), 147-162. https://doi.org/10.1046/J.1095-8312.2002.00012.X

Rosenberg, M. S. (2014). Contextual cross-referencing of species names for fiddler crabs (Genus Uca): an experiment in cyber-taxonomy. PLoS ONE, 9(7), e101704. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0101704

Rosenberg, M. S. (2020). A fresh look at the biodiversity lexicon for fiddler crabs (Decapoda: Brachyura: Ocypodidae). Part 2: Biogeography. J. Crust. Biol., 40(4), 365-383. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcbiol/ruaa029

Rosenberg, M. S. (2023). Fiddler Crab Guide: Pacific Coast of the Americas. iNaturalist. https://www.inaturalist.org/journal/msr/82286-fiddler-crab-guide-pacific-coast-of-the-americas

Shih, H. T., Ng, P. K. L. & Christy, J. H. (2015). Uca (Petruca), a new subgenus for the rock fiddler crab Uca panamensis (Stimpson, 1859) from Central America, with comments on some species of the American broad-fronted subgenera. Zootaxa, 4034(3), 471-494. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4034.3.3

Shih, H. T., Ng, P. K. L., Davie, P. J. F., Schubart, C. D., Türkay, M., Naderloo, R. & Jones, D. (2016). Systematics of the family Ocypodidae Rafinesque, 1815 (Crustacea: Brachyura), based on phylogenetic relationships, with a reorganization of subfamily rankings and a review of the taxonomic status of Uca Leach, 1814, sensu lato and its subgenera. Raffles Bull. Zool., 64, 139-175. https://lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/app/uploads/2017/06/64rbz139-175.pdf

Smith, N. F., Wilcox, C. & Lessmann, J. M. (2009). Fiddler crab burrowing affects growth and production of the white mangrove (Laguncularia racemosa) in a restored Florida coastal marsh. Mar. Biol., 156, 2255-2266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-009-1253-7

1 Universidad de Panamá, Departamento de Biología Marina, Centro Regional Universitario de Veraguas.

2 Centro de Capacitación, Investigación y Monitoreo de la Biodiversidad en el Parque Nacional Coiba.

3 Sistema Nacional de Investigación, Secretaría Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación, Panamá.

roberto.lombardo@up.ac.pa* ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0279-8621