ISSN: 1659-455X • e-ISSN: 1659-407X

Vol. 16 (2), julio-diciembre 2024

Recepción 9 abril 2024 • Corregido 15 julio 2024 • Aceptado 22 julio 2024

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15359/revmar.16-2.1

|

Selectivity of gillnets for the capture of Selene peruviana and Peprilus medius in the Ecuadorian Pacific Selectividad de las redes de enmalle para la captura de Selene peruviana y Peprilus medius en el Pacífico ecuatoriano Kléver Mendoza-Nieto1,2*, Jesús Briones-Mendoza1 & José J. Alió3 |

ABSTRACT

In the Ecuadorian Pacific, Selene peruviana and Peprilus medius are target species for artisanal fishing caught with gillnets that constitute an important fishery resource for local consumption, given that they are highly valued species due to their low cost and their contribution of high biological value protein. However, no studies have determined selectivity in capturing these species. This study evaluates the selectivity of monofilament surface gillnets with mesh sizes of 3” (7.62 cm) and 3 ½” (8.89 cm), mostly used by artisanal fishers. Data were obtained from severeal fishing operations within the coastal zone of 8 nautical miles (nm) in Manabí, Ecuador, in 2017, between 6:00 pm and 6:00 am. Selectivity parameters and curves were evaluated through multi-model analysis using the SELEC method. The lognormal model showed the best fit with modal lengths of 24.23 and 21.96 cm for S. peruviana and P. medius, respectively, and selection factors of 3.23 and 3.11. The optimal mesh sizes were calculated at 7.20 and 6.91 cm, respectively, which are smaller than those commonly used by most local artisanal fishers. Therefore, it can be inferred that the size distribution of the captured species follows a lognormal distribution, suggesting that gillnets have a higher probability of capturing larger fish.

Keywords: Carangidae, Stromateidae, artisanal fishing, selectivity, Ecuadorian Pacific

RESUMEN

En el Pacífico ecuatoriano, Selene peruviana y Peprilus medius son especies objetivos de la pesca artesanal capturadas con redes de enmalle, y constituyen un importante recurso pesquero para el consumo local al ser especies muy cotizadas por su bajo costo y su aporte de proteína con alto valor biológico. Sin embargo, no existen estudios que determinen la selectividad en la captura de estas especies. El presente estudio evalúa la selectividad de redes de enmalle de superficie de monofilamento con luz de malla de 3” (7.62cm) y 3 ½” (8.89 cm), mayormente utilizadas por los pescadores artesanales. Los datos provinieron de diversas operaciones de pesca dentro de la zona costera de 8 millas náuticas (M) en Manabí, Ecuador, durante 2017, entre 6:00 p. m. y 6:00 a. m. Los parámetros y curvas de selectividad se evaluaron mediante análisis multimodelo utilizando el método SELEC. El modelo log-normal mostró el mejor ajuste con longitudes modales de 24.23 y 21.96 cm para S. peruviana y P. medius, respectivamente, y factores de selección de 3.23 y 3.11. Los tamaños de malla óptimos calculados fueron de 7.20 y 6.91 cm, correspondientemente, que son más pequeños que los utilizados por la mayoría de los pescadores artesanales locales. Por lo tanto, se puede inferir que la distribución de tamaños de las especies capturadas sigue una distribución log-normal, lo que sugiere que las redes de enmalle tienen una mayor probabilidad de capturar peces más grandes.

Palabras clave: Carangidae, Stromateidae, pesca artesanal, selectividad, Pacifico Ecuatoriano

In fisheries assessment, the size of commercially important species depends on their biology, growth, and age at sexual maturity, as well as environmental conditions and availability of food in their habitat (Narváez Barandica et al. 2013; Altın, 2023; Balbontín et al. 2023).

The use of size-based methods to assess fish populations has been employed for several years and continues to be used today due to the ease and availability of data for their implementation (Gulland & Rosenberg, 1992; Fisch et al. 2019; Fisch et al. 2021). As the level of exploitation of a resource or fishing area increases, there is a tendency among fishers to decrease the selectivity of their fishing gear, resulting in an increase in bycatch and the capture of undersized individuals (Duarte et al. 2006; Rezende et al. 2019; Martin Gonzalez et al. 2021). The decrease in fish abundance promotes the enlargement of fishing gear, leading to increased fishing power, which, in some cases, hinders the escape of organisms that have not reached their size at sexual maturity, hence not contributing with new individuals to the population (McClanahan & Mangi, 2004; Altamar et al. 2015).

Selective fishing gear is essential to ensure sustainable fishing and minimize the capture of non-target species (FAO, 2018; Lucchetti et al. 2023; Bhanja et al. 2024). This highlights the importance of selectivity as a fundamental tool in fisheries management to achieve sustainability (Troadec, 1984; Gilman et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2022).

Size selectivity, both within and among species, provides valuable information to establish management measures in fisheries (Sparre & Venema, 1997). Reeves et al. (1992) emphasize the need to consider the ability of a fish to escape through a mesh opening or become trapped in it, with both horizontal and vertical dimensions of the mesh opening being key factors when designing fishing gear. Size selectivity, to some extent, could be regulated by gear design. Ideally, a certain mesh size should allow for the release of all fish below a certain size (FAO, 1995; Cuende et al. 2020; Yu et al. 2023).

Gillnets are one of the most common and widely used fishing gear in artisanal fisheries (Rojo Vázquez, 1997), offering advantages over other fishing gear due to their easy use, low cost, and ability to be set at various depths (Hovgård & Lassen, 2000; Sánchez-González & Casals, 2022).

It is considered that one of the most important characteristics of gillnets is their selectivity (Rojo Vázquez, 1997; Humphries et al. 2019; Kim et al. 2021). The catch probability of a gillnet depends on specific gear characteristics and the morphology of the target species (Gulland & Harding, 1961; Holst et al. 1998). The effectiveness of selectivity research with gillnets hinges on acquiring adequate catches, yet there is no exact method for determining the minimum number of attempts needed since it varies based on capture efficiency (Altamar et al. 2020).

In Ecuador, gillnets are not regulated, unlike other fishing gear such as trawls, beach seines, purse seines, and hooks, which have a more comprehensive regulatory framework. Furthermore, there are no studies on the selectivity of gillnets for capturing Selene peruviana (Guichenot, 1866) and Peprilus medius (Peters, 1869), despite their local commercial importance as a target for artisanal fisheries. Therefore, the present research aims to analyze the selectivity of gillnets in catching S. peruviana and P. medius in the Ecuadorian Pacific, as well as identifying the most suitable mesh sizes to promote sustainable fishing.

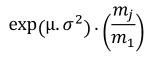

For the selectivity analysis of gillnets, data were obtained through fishing operations within 8 nautical miles (nm) off the coast of Manabí, Ecuador (1° 6’ 16.1’’ S, 80° 56’ 17.0’’ W) and (0° 47’ 17.60’’ S, 80° 35’ 41.26’’ W) (Fig. 1). Fishing operations were conducted during 2017 on different trips, between 6:00 pm and 6:00 am, depending on the tide since fishers carry their boats from shore to the sea during high tide. Two surface gillnets made of monofilament with mesh sizes of 3” (7.62 cm) and 3 ½” (8.89 cm) 3.5 m long were used for capturing S. peruviana and P. medius. The net panels were attached to upper- and lower-line ropes, which were made with twisted polyethylene (PE) thread of 5 mm in diameter, where floats and weights were hung, respectively. During the fishing operation, the catch was separated into plastic containers on board. Once organisms were collected, their total length (cm) was measured using a measuring tape with 1 mm precision.

Fig. 1. Location of the study area, Los Arenales and Las Piñas, Manabí, Ecuador

Fig. 1. Ubicación de la zona de estudio, Los Arenales y Las Piñas, Manabí Ecuador

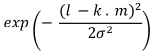

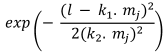

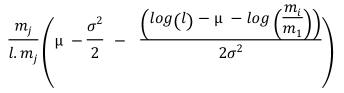

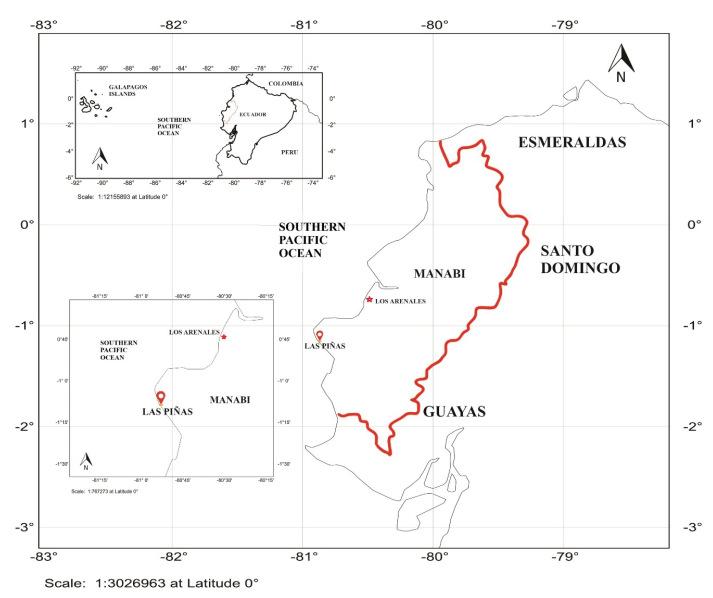

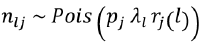

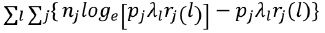

Two methods were used to evaluate the selectivity parameters of the two mesh sizes, the indirect method proposed by Holt (1963), in which data was categorized into size intervals for each type of net used, and a multimodel analysis, using four unimodal selection curve models: normal location, normal scale, gamma, and lognormal. These models were established using the SELECT method (Millar, 1992) and implemented using the “Selec_millar” and “gillnetfit” packages (Millar, 2010) in the statistical software R. The SELECT method enables the estimation of selection curves for gillnets and their retention probabilities using comparative catch data (Queirolo et al. 2013). The number of fish of length l captured with a mesh size follows a Poisson distribution  (Millar, 1995) and is defined by the following equation

(Millar, 1995) and is defined by the following equation

While the likelihood function for nlj is

Where: nj is the number of fish of length l captured by mesh size j; pj is the relative fishing intensity, representing the probability that a fish of length l makes contact with mesh size j; λl is the abundance of fish in size class l; rj(l) is the retention probability of fish of length l in mesh size j.

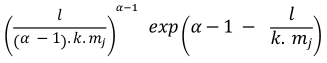

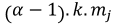

The dependent variable was the retention probability of fish of length l in the gillnet of mesh size j, while the independent variables were the mesh size of the gillnet (j) and the length of the captured fish (l). The method utilizes a Generalized Linear Model (GLM), commonly used in gillnets and hooks (Millar & Holst, 1997). These models were fitted to the capture data obtained during fishing operations, using probability functions such as the Poisson distribution and likelihood functions to assess their fit to the observed data and estimate the model parameters. To find the model with the best fit, quasi-deviance residuals were calculated and incorporated into the corrected quasi-Akaike Information Criterion (QAICc) scores for each combination of species and selection curve (Smith et al. 2017; Burnham & Anderson, 2002). The model with the lowest QAICc is assumed to provide the best fit to the data. The models generated using the SELECT method are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Selectivity curve equations for evaluated models and equations for calculating modal lengths (cm) of S. peruviana and P. medius

Cuadro 1. Ecuaciones de curvas de selectividad para los modelos evaluados y ecuaciones para cálculo de longitudes modales (cm) de S. peruviana y P. medius

|

Model |

Modal length |

|

|

Normal location |

|

|

|

Normal scale |

|

|

|

Gamma |

|

|

|

Log-normal |

|

|

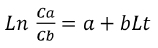

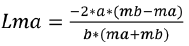

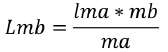

In addition, the indirect method proposed by Holt (1963) was used, in which data was categorized into size intervals for each type of net used (Ca and Cb). The logarithms of the proportions can be expressed as a linear function of fish length (Lt):

(1)

(1)

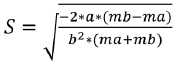

Where Cb represents the catch of the large mesh (mb) while Ca the catch of the small mesh (ma). The parameters a and b of the regression were used to calculate the optimal capture size (Lm) and the standard deviation (S) for each net using the following equations:

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

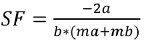

The Selection Factor SF is calculated using the equation (Holt, 1963):

(4)

(4)

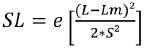

The selectivity curve was fitted to the equation:

(5)

(5)

Where SL is the selection probability for a fish of length L; Lm is the optimal size, and S is the standard deviation.

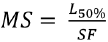

Recommended mesh sizes (MS) were calculated based on the optimal capture size for each mesh size and the selection factors (SF) obtained from the best fit, and considering the average size at sexual maturity,

After verifying the normality and homoscedasticity of data, a Student’s t-test was applied to determine significant differences in catch sizes of each species with different mesh sizes and to compare the optimal capture sizes. When these assumptions were not met, a Mann-Whitney test was used (Zar, 2013). The statistical analysis was conducted with a 95% confidence level using the R programming language (R Core Team, 2021).

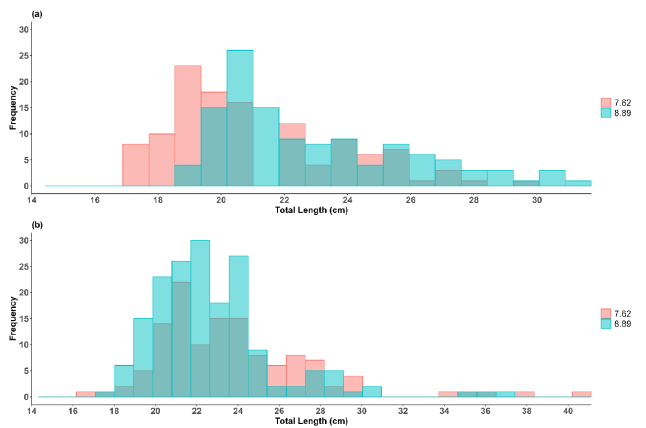

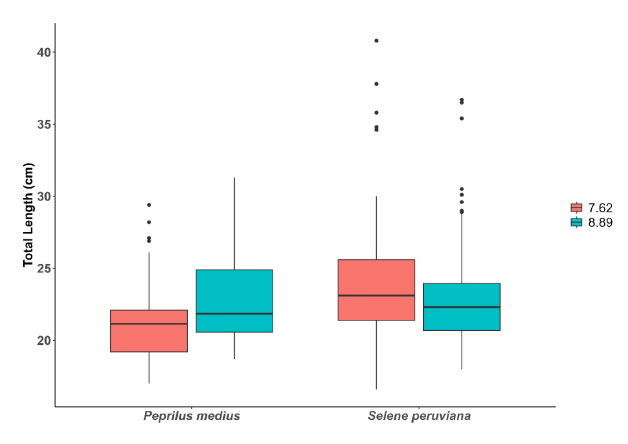

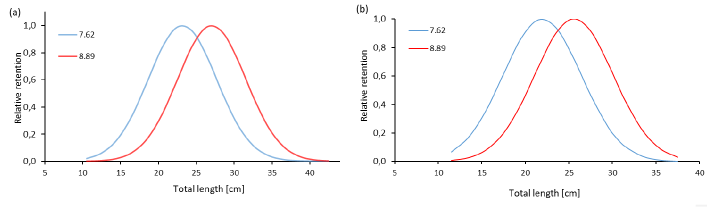

A total of 598 specimens were analyzed for gillnet selectivity, and 324 individuals of S. peruviana were obtained, with average sizes of 23.76 ± 3.84 and 22.76 ± 3.08 cm TL for gillnets with 7.62 cm and 8.89 cm mesh size, respectively (Fig. 2). Significant differences were observed (U = 9 181; P < 0.05) between net types. In the case of P. medius, 274 specimens were obtained, with average sizes of 21.14 ± 2.70 and 22.70 ± 2.74 cm TL for gillnets with 7.62 cm and 8.89 cm mesh size, respectively, also showing significant differences (U = 12 151.5; P < 0.05). In general, the smaller mesh size net captured smaller individuals of S. peruviana on average, while larger individuals of P. medius were captured using the larger mesh size net. However, for both species, the smaller mesh size net had the widest range of sizes (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Size frequency for a) Peprilus medius and b) Selene peruviana by mesh size

Fig. 2. Frecuencia de tallas para a) Peprilus medius y b) Selene peruviana por luz de malla

Fig. 3. Total length of captured P. medius and S. pruviana from nets with mesh sizes 7.62 and 8.89 cm

Fig. 3. Longitud total de ejemplares capturados de P. medius y S. pruviana con redes de luz de malla 7.62 y 8.89 cm

The SELECT method applied to the lengths of S. peruviana determined the selectivity parameters of the models, with the lognormal unimodal model showing the best fit (QAICc 13.44) and being used for the selectivity curves with parameters µ = 3.23 and σ = 0.21. Conversely, the normal scale model (normal with different variances) showed the poorest fit. For P. medius, the selectivity parameters also indicated the lognormal model as the best fit (QAICc 23.16), with µ = 3.03 and σ = 0.15, and a modal length of 20.24 ± 0.39 and 23.42 ± 0.3. Similarly, the normal scale model showed the poorest fit (Table 2).

Table 2. Parameters of selectivity, mode and deviance of models for S. peruviana and P. medius

Cuadro 2. Parámetros de selectividad, moda y desviación de modelos para S. peruviana y P. medius

|

Species |

n |

Model |

Parameters |

Mode |

Deviance residuals |

QAICc |

|

Selene peruviana |

324 |

Normal location |

k, σ = (3.21; 5.84) |

24.53±1.01 |

5.81 |

15.66 |

|

Normal scale |

k1, k2 = (3.35; 0.54) |

25.52±1.13 |

9.07 |

22.18 |

||

|

Gamma |

α, k = (21.61; 0,15) |

24.23±1.01 |

5.81 |

15.66 |

||

|

Log-normal |

µ, σ = (3.23; 0.21) |

24.23±0.97 |

4.7 |

13.44 |

||

|

Peprilus medius |

284 |

Normal location |

k, σ = (2.89; 3.89) |

22.05±0.52 |

10.17 |

24.38 |

|

Normal scale |

k1, k2 = (2.95; 0.22) |

20.50±0.54 |

11.78 |

27.60 |

||

|

Gamma |

α, k = (38.46; 0,07) |

22.13±0.53 |

10.17 |

24.38 |

||

|

Log-normal |

µ, σ = (3.11; 0.16) |

21.96±0.52 |

9.56 |

23.16 |

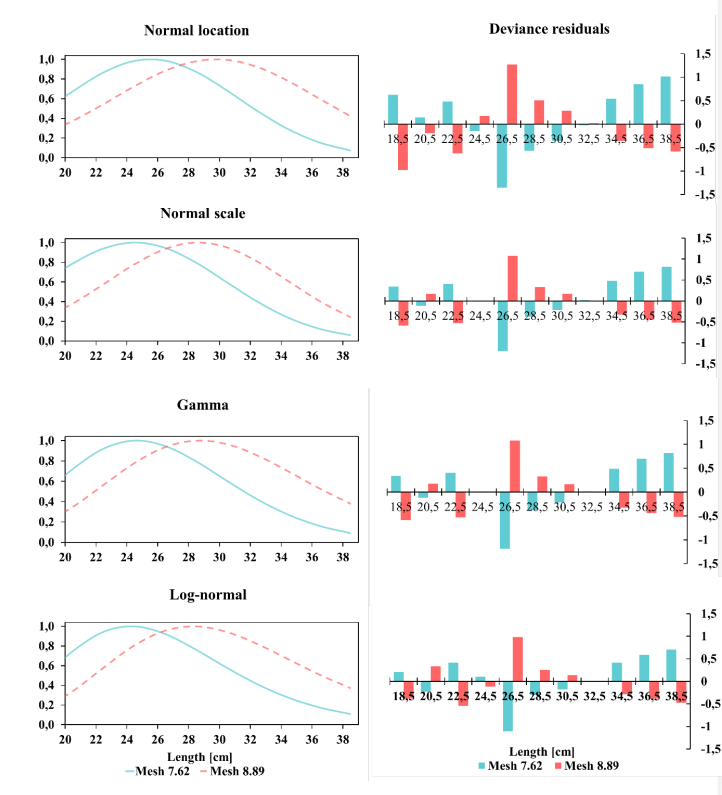

Regarding the fitted selectivity curves, two curves were estimated for each of the four adjusted models of S. peruviana. The deviation analysis using the lognormal distribution model provided the best fit to the size-at-capture of S. peruviana, which corresponded to the optimal capture sizes of 24.23 ± 0.27 and 28.20 ± 0.30 cm TL for nets with mesh sizes of 7.62 and 8.89 cm, respectively. Size intervals ranged from 16.6 to 40.80 cm TL for the net with the smaller mesh size, and from 18.70 to 36.70 cm TL for the net with the larger mesh size (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Adjustment to models and residual deviation of S. peruviana with nets with mesh sizes 7.62 cm and 8.89 cm

Fig. 4. Ajuste a los modelos y desviación residual de S. peruviana con redes de malla de 7.62 cm y 8.89 cm

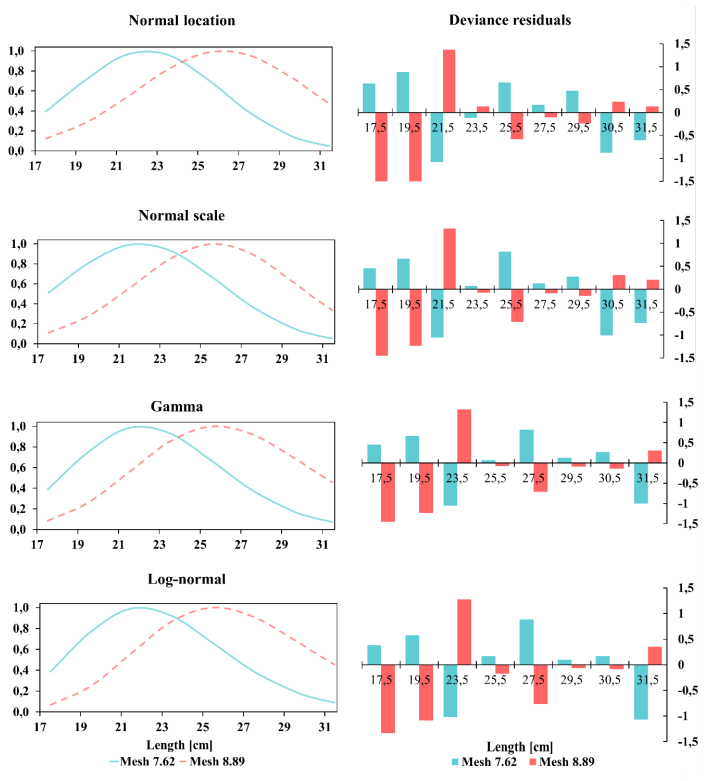

Similar fitted selectivity curves were obtained for P. medius, corresponding to the optimal capture sizes. Likewise, the lognormal distribution model provided the best fit with an optimal capture size of 21.96 ± 0.52 and 25.49 ± 0.30 cm TL for nets with mesh sizes of 7.62 cm and 8.89 cm, respectively, and a size interval between 17.0 and 29.4 cm TL for the net with the smaller mesh size, and a size interval between 18.70 cm and 31.30 cm TL for the net with the larger mesh size (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Adjustment to models and residual deviation of P. medius captured with nets with mesh sizes 7.62 cm and 8.89

Fig. 5. Ajuste a los modelos y desviación residual de P. medius capturado con redes de luz de malla 7.62 cm y 8.89

Using Holt’s direct method, an optimal capture size of 23.7 cm LT, an SF of 3.04, and a correlation coefficient of r = 0.95 (F=37.17; P < 0.05) were obtained for S. peruviana, while, an optimal capture size of 21.9 cm TL, an SF of 2.88, and a correlation coefficient of r = 0.94 (F = 32.20; P < 0.05) were obtained for P. medius (Fig. 6). The optimal catch sizes for S. peruviana and P. medius using Holt and SELECT methods, respectively, did not show significant differences (t = 0.15; P > 0.05) and (t = 0.02; P > 0.05).

Fig. 6. Selectivity curves using Holt’s 1963 indirect method for a) S. peruviana and b) P. medius

Fig. 6. Curvas de selectividad utilizando el método indirecto de Holt 1963, para a) S. peruviana y b) P. medius

In the multimodel analysis of selectivity of the 7.62 and 8.89 cm mesh size gillnets, commonly used by artisanal fishers in Ecuador for the capture of S. peruviana and P. medius, it was observed that the estimated modal lengths in the present study were smaller than the reported sizes at sexual maturity in the Ecuadorian Pacific, which were 23.27 cm TL for combined sexes of S. peruviana and 21.5 cm TL for P. medius (Mendoza-Nieto et al. 2022; Mendoza-Nieto et al. 2023). Only the normal scale model showed a size below sexual maturity in P. medius, but overall, the lognormal model showed the best fit for both species. However, in many selectivity studies, normal scale models, as well as bimodal models, tend to provide the best fits (Fujimori & Tokai, 2001; dos Santos et al. 2003; Erzini et al. 2003; Carol & García-Berthou, 2007). On the other hand, fitting with gamma, logarithmic, normal, or multimodal models is mostly used when a large number of fish are captured and data is right-skewed (Millar, 1992).

The better fit with the lognormal model can be attributed to the fact that it is a continuous probability distribution that is applied to random variables and exhibits a normal distribution when the natural logarithm of the variable is taken. It is primarily employed in modeling data with positive skewness (Nagatsuka & Balakrishnan, 2013; Limpert & Stahel, 2017; Feng et al. 2020).

This confirms that gillnets have a higher size selectivity, with a relatively narrow size interval (dos Santos et al. 2003), hence it can be inferred that the size distribution of S. peruviana and P. medius captured by gillnets follows a lognormal distribution, suggesting that gillnets have a higher probability of capturing larger fish (Saber & Aly, 2023). However, other factors such as the behavior and morphology of species also play a crucial role in the likelihood of capturing individuals of different sizes. Some species may more easily avoid or escape from nets with larger meshes, while others become trapped in smaller meshes. Furthermore, the size and body shape of individuals also affect their retention capacity, thus influencing the capture of fish of different sizes (Lemke & Simpfendorfer, 2023)

The selectivity efficiency of the fishing gear depends on the encounter probability and the likelihood of capture upon encounter (Tapia Varela, 2003). Therefore, the fishing zone should also be considered (Saber et al. 2022), as both S. peruviana and P. medius inhabit shallower waters close to the coast in their juvenile stages, unlike adults. Their habitat may include reef areas, bays, estuaries, and river mouths (Fischer et al. 1995), where they experience a higher incidence of natural mortality and lower fishing mortality due to their limited recruitment to the fishing area (Inga Barreto et al. 2008).

It is important to consider that S. peruviana is a larger species compared to P. medius. This is evident in the higher number of outliers in the gillnet with a mesh size of 7.62 cm, unlike P. medius. It should also be mentioned that the capture of S. peruviana and P. medius with gillnets is not an ongoing activity but rather one conducted by artisanal fishers seasonally and in specific areas. Therefore, the efficiency of the gear also depends to a large extent on the stratification of the gear in the water column and the fishing season (Queirolo et al. 2013).

Despite the lack of fishery management measures for gillnets targeting S. peruviana and P. medius in Ecuador, data analysis—considering the optimal catch sizes for each mesh size and the specific selection factors for each species based on the best fit—suggests that the recommended mesh sizes (RMS) are 7.20 cm and 6.91 cm for capturing S. peruviana and P. medius, respectively, based on the average size at sexual maturity reported in the literature for similar gillnets. These recommended mesh sizes are smaller than the 7.62 cm and 8.89 cm meshes evaluated in this study, which are commonly used by artisanal fishers in Ecuador, implying that at least 50% of organisms would have contributed with new individuals to the population. However, the use of 6.35 cm (2 1/2”) gillnets has also been observed to a lesser extent.

Although the SELECT method is primarily used to assess selectivity with more than two mesh sizes, some authors have applied it to assess selectivity even with just two gillnets. This is because these log-linear models have the advantage of assuming that the variances of the two selectivity curves are heterogeneous, unlike the linear regression model (González et al. 2008; Intchama, 2023).

It is also important to highlight that, despite the selectivity of gillnets, their improper use and abandonment due to wear and tear, which shortens their lifespan (Brinkhof et al. 2023), can harm aquatic ecosystems. It has been reported that artisanal fishers in Ecuador may lose up to a maximum of 2 net panels per fishing trip (Zambrano et al. 2021). These abandoned nets can act as ghost fishing gear since they are made of non-biodegradable monofilament material, persisting for years and causing ecological damage to marine fauna (Campoy & Beiras, 2019). An alternative could be to use gillnets made of multifilament material of natural fibers, which makes them more environmentally friendly and reduces the impacts of ghost fishing. However, selectivity studies are needed to assess their effectiveness.

To promote sustainable fishing, it is important to expand the analysis beyond modifications in mesh size (Breen et al. 2020). Considering other adaptations in the design of nets is crucial. Aspects such as the hanging ratio, which affects the mobility of the net in the water and can increase the likelihood of catching more active and agile species; the type of mesh material (monofilament and multifilament), where multifilament nets, due to their finer texture, can impact selectivity by allowing the capture of unwanted or juvenile species; and the position in the water column, as some species tend to swim at different depths at various stages of their life cycle. Additionally, more detailed patterns of selectivity have been uncovered, including the relevance of visual, auditory, and tactile signals for species, which play an essential role in fish capture (Abangan et al. 2023). Therefore, these factors require detailed analysis to accurately determine their effectiveness (Brandt von, 1975; Altamar et al. 2020) .

The analysis of gillnet selectivity in the artisanal fishing of S. peruviana and P. medius in Ecuador reveals significant differences in capture sizes depending on mesh size. Lognormal models showed the best fit, suggesting high size selectivity in the nets. Despite the lack of fishery management measures, recommended mesh sizes for more sustainable fishing are smaller than those commonly used, aiding in the contribution of new individuals to the population. However, challenges such as material abandonment and improper use remain significant concerns. Additionally, the importance of considering further studies and promoting more sustainable fishing practices is emphasized.

The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation to Universidad Laica Eloy Alfaro de Manabí, for financing the project “Evaluation of biological parameters and population dynamics for the management of marine resources.” The authors would also like to thank the reviewers who improved the document with their comments.

Abangan, A. S., Kopp, D. & Faillettaz, R. (2023). Artificial intelligence for fish behavior recognition may unlock fishing gear selectivity. Front. Mar. Sci, 10, 1010761. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1010761

Altamar, J., Manjarrés-Martínez, L., Duarte, L. O., Cuello, F. & Escobar-Toledo, F. (2015). ¿Qué tamaños deberíamos pescar? Colombia. Autoridad Nacional de Acuacultura y Pesca (AUNAP) & Universidad del Magdalena.

Altamar, J., Wong-Lubo, J., De la Hoz, J. D. & Martínez-Dallos, I. (2020). Evaluación de la selectividad de redes de enmalle y líneas de mano para la captura de cojinoa (Caranx crysos) en áreas de influencia marina del Parque Nacional Natural Tayrona. Bol. Investig. Mar. Costeras, 49(Supl. Esp), 209-2022. https://doi.org/10.25268/bimc.invemar.2020.49.SuplEsp.1074

Altın, A. (2023). Rasgos de vida temprana del sargo común, Diplodus vulgaris (Perciformes: Sparidae), que habita las aguas poco profundas de la isla Gökçeada, Turquía. Cienc. Mar., 49, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.7773/cm.y2023.3344

Balbontín, F., López-Soto, E., Bravo, R., Saavedra-Nievas, J. C., Troncoso, P., Ojeda, V., … & Herrera, G. (2023). Long-term trends in length and age at sexual maturity of hoki Macruronus magellanicus and southern hake Merluccius australis from Chilean Patagonia. Rev. Biol. Mar. Oceanogr, 58(1), 32-48. https://doi.org/10.22370/rbmo.2023.58.1.4150

Bhanja, A., Payra, P. & Mandal, B. (2024). A Study on the selectivity of different fishing gear. Ind. J. Pure App. Biosci, 12(2), 8-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.18782/2582-2845.9072

Brandt, A. von. (1975). Enmeshing nets: Gillnets and entangling nets. The theory of their efficiency. Technical paper, 23. Scotland. European Inland Fisheries Advisory Commission.

Breen, M., Anders, N., Humborstad, O.-B., Nilsson, J., Tenningen, M. & Vold, A. (2020). Catch welfare in commercial fisheries. In T. S. Kristiansen, A. Fernö, M. A. Pavlidis & H. van de Vis (Eds.), The welfare of fish (pp. 401-437). Germany, Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41675-1_17

Brinkhof, I., Herrmann, B., Larsen, R. B., Brinkhof, J., Grimaldo, E. & Vollstad, J. (2023). Effect of gillnet twine thickness on capture pattern and efficiency in the Northeast.Arctic cod (Gadus morhua) fishery. Mar. Pollut. Bull., 191, 114927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2023.114927

Burnham, K. P. & Anderson, D. R. (Eds.). (2002). Advanced issues and deeper insights. In K. P. Burnham (Ed.), Model selection and multimodel inference: A practical information-theoretic approach (pp. 267-351). USA, Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-22456-5_6

Campoy, P. & Beiras, R. (2019). Revisión: Efectos ecológicos de macro-, meso-y microplásticos. Proyecto REPESCAPLAS2. Actividad 4.3. Spain. Universidad de Vigo.

Carol, J. & García-Berthou, E. (2007). Gillnet selectivity and its relationship with body shape for eight freshwater fish species. J. Appl. Ichthyol., 23(6), 654-660. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0426.2007.00871.x

Cuende, E., Arregi, L., Herrmann, B., Sistiaga, M. & Aboitiz, X. (2020). Prediction of square mesh panel and codend size selectivity of blue whiting based on fish morphology. ICES J. Mar. Sci., 77(7-8), 2857–2869. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsaa156

dos Santos, M., Gaspar, M., Monteiro, C. & Erzini, K. (2003). Gill net selectivity for European hake Merluccius merluccius from southern Portugal: Implications for fishery management. Fish. Sci., 69(5), 873-882. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1444-2906.2003.00702.x

Duarte, L., Gómez-Canchong, P., Manjarrés, L., García, C., Escobar, F., Altamar, J., …. & Cuello, F. (2006). Variabilidad circadiana de la tasa de captura y la estructura de tallas en camarones e ictiofauna acompañante en la pesquería de arrastre del Mar Caribe de Colombia. Invest. Mar., 34(1), 23-42. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-71782006000100003

Erzini, K., Gonçalves, J., Bentes, L., Lino, P., Ribeiro, J. & Stergiou, K. (2003). Quantifying the roles of competing static gears: Comparative selectivity of longlines and monofilament gill nets in a multi-species fishery of the Algarve (southern Portugal). Sci. Mar., 67(3), 341-352.

FAO. (1995). Código de Conducta para la Pesca Responsable. Rome: FAO.

FAO. (2018). Directrices voluntarias para lograr la sostenibilidad de la pesca en pequeña escala en el contexto de la seguridad alimentaria y la erradicación de la pobreza. Rome: FAO.

Feng, M., Deng, L.-J., Chen, F., Perc, M. & Kurths, J. (2020). The accumulative law and its probability model: An extension of the Pareto distribution and the log-normal distribution. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci., 476(2237), 20200019. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2020.0019

Fisch, N. C., Bence, J. R., Myers, J. T., Berglund, E. K. & Yule, D. L. (2019). A comparison of age- and size-structured assessment models applied to a stock of cisco in Thunder Bay, Ontario. Fish. Res., 209, 86-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2018.09.014

Fisch, N., Camp, E., Shertzer, K. & Ahrens, R. (2021). Assessing likelihoods for fitting composition data within stock assessments, with emphasis on different degrees of process and observation error. Fish. Res., 243, 106069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2021.106069

Fischer, W., Krupp, F., Schneider, W., Sommer, C., Carpenter, K. & Niem, V. (1995). Guía FAO para la identificación de especies para los fines de la pesca. Pacífico centro-oriental Vol II. Vertebrados - Parte 1. Rome: FAO.

Fujimori, Y. & Tokai, T. (2001). Estimation of gillnet selectivity curve by maximum likelihood method. Fish. Sci., 67(4), 644-654. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1444-2906.2001.00301.x

Gilman, E., Chaloupka, M., Bach, P., Fennell, H., Hall, M., Musyl, M., Piovano, S., Poisson, F. & Song, L. (2020). Effect of pelagic longline bait type on species selectivity: A global synthesis of evidence. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish., 30(3), 535-551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-020-09612-0

González, Á., Mendoza, J., Arocha, F. & Márquez, A. (2008). Selectividad de la red de enmalle en la captura del bagre rayado Pseudoplatystoma fasciatum de la cuenca del Orinoco medio. Zootec. Trop., 26(1), 63-70.

Gulland, J. & Harding, D. (1961). The Selection of Clarias mossambicus (Peters) by Nylon Gill Nets. ICES J. Mar. Sci., 26(2), 215-222. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/26.2.215

Gulland, J. & Rosenberg, A. (1992). Examen de los métodos que se basan en la talla para evaluar las poblaciones de peces. Doc. Tec. Pesca 323. Rome. FAO.

Holt, S. J. (1963). The selectivity of fishing gear. In ICNAF/ICES/FAO (Eds.). A method for determining gear selectivity and its application. (pp.106-115). Special Publication, 5. Canada. International Commission for the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries.

Holst, R., Madsen, N., Moth-Poulsen, T., Fonseca, P. & Campos, A. (1998). Manual for gillnet selectivity. Inform No. 43. Denmark. European Commission.

Hovgård, H. & Lassen, H. (2000). Manual on Estimation of Selectivity for Gillnet and Longline Gears in Abundance Surveys. Fisheries Technical Paper 397. Rome. FAO.

Humphries, A. T., Gorospe, K. D., Carvalho, P. G., Yulianto, I., Kartawijaya, T. & Campbell, S. J. (2019). Catch Composition and Selectivity of Fishing Gears in a Multi-Species Indonesian Coral Reef Fishery. Front. Mar. Sci., 6, 378. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00378

Inga Barreto, C., Rujel Mena, J., Ordinola Zapata, E. & Gómez Sulca, E. (2008). El chiri, Peprilus medius (Peters) en Tumbes, Perú. Parámetros biológico-pesqueros y talla mínima de captura. Informe, 45(3). Instituto del Mar del Perú. 35(3), 209-2014.

Intchama, F. J. (2023). Dinámica de las poblaciones de recursos demersales marinos costeros compartidos en el áfrica occidental: Estudio de caso de la especie Pseudotolithus elongatus (Bowdich, 1825) del ecosistema marino de la República de Guinea Bissau y la República de Guinea (Unpublished doctoral dissertation), Universidad de Cádiz, Spain. https://rodin.uca.es/handle/10498/29452

Kim, P., Kim, H. & Kim, S. (2021). Mesh Size Selectivity of Tie-Down Gillnets for the Blackfin Flounder (Glyptocephalus stelleri) in Korea. Appl. Sci., 11(21), 9810. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11219810

Lemke, L. R. & Simpfendorfer, C. A. (2023). Gillnet size selectivity of shark and ray species from Queensland, Australia. Fish. Manag. Ecol., 30(3), 300-309. https://doi.org/10.1111/fme.12620

Limpert, E. & Stahel, W. A. (2017). The Log-Normal Distribution. Significance, 14(1), 8-9.

Lucchetti, A., Melli, V. & Brčić, J. (2023). Editorial: Innovations in fishing technology aimed at achieving sustainable fishing. Front. Mar. Sci., 10, 1310318. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1310318

Martín González, G., Wiff, R., Marshall, C. T. & Cornulier, T. (2021). Estimating spatio-temporal distribution of fish and gear selectivity functions from pooled scientific survey and commercial fishing data. Fish. Res., 243, 106054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2021.106054

McClanahan, T. R. & Mangi, S. C. (2004). Gear-based management of a tropical artisanal fishery based on species selectivity and capture size. Fish. Manag. Ecol., 11(1), 51-60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2400.2004.00358.x

Mendoza-Nieto, K., C-Soriguer Escofet, M., Carrera-Fernández, M., Mendoza-Nieto, K., C-Soriguer Escofet, M. & Carrera-Fernández, M. (2023). Reproductive cycle and sexual maturity size of landed Selene peruviana (Perciformes: Carangidae) on the coasts of the Ecuadorian Pacific. Cienc. Mar., 49, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.7773/cm.y2023.3363

Mendoza-Nieto, K., Soriguer-Escofet, M. C., Carrera-Fernández, M., Alió, J. J. & Figueroa-Chávez, F. (2022). Reproductive dynamics of Peprilus medius captured in the Ecuadorian Pacific. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res., 50(5), 660-668. https://doi.org/10.3856/vol50-issue5-fulltext-2928

Millar, R. B. (1992). Estimating the Size-selectivity of Fishing Gear by Conditioning on the Total Catch. J. Am. Stat. Assoc., 87(420), 962-968. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1992.10476250

Millar, R. B. (1995). The functional form of hook and gillnet selection curves cannot be determined from comparative catch data alone. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci., 52(5), 883-891. https://doi.org/10.1139/f95-088

Millar, R. B. (2010). Reliability of size-selectivity estimates from paired-trawl and covered-codend experiments. ICES J. Mar. Sci., 67(3), 530-536. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsp266

Millar, R. B. & Holst, R. (1997). Estimation of gillnet and hook selectivity using log-linear models. ICES J. Mar. Sci., 54(3), 471-477. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmsc.1996.0196

Nagatsuka, H. & Balakrishnan, N. (2013). Parameter and quantile estimation for the three-parameter lognormal distribution based on statistics invariant to unknown location. J. Stat. Comput. Simul., 83(9), 1629-1647. https://doi.org/10.1080/00949655.2012.667410

Narváez Barandica, J., Maestre, J., Blanco, J., Bolívar, F., Rivera, R., Álvarez, T., Mora, A. & Riascos, O. (2013). Tallas mínimas de captura para el aprovechamiento sostenible de las principales especies de peces comerciales de Colombia (Primera). Colombia. Editorial, UNIMAGDALENA.

Queirolo, D., Ahumada, M., Gaete, E., Hurtado, F., Merino, J., Montenegro, I., Escobar, R. & Zamora, V. (2013). Selectividad de redes de enmalle en la pesquería artesanal de merluza común. Informe Final, FIP-IT/2011-10. Chile. Fondo de Investigación Pesquera

R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, USA. http://www.rstudio.com/

Reeves, S., Armstrong, D., Fryer, R. & Coull, K. (1992). The effects of mesh size, cod-end extension length and cod-end diameter on the selectivity of Scottish trawls and seines. ICES J. Mar. Sci., 49(3), 279-288. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/49.3.279

Rezende, G. A., Rufener, M.-C., Ortega, I., Ruas, V. M. & Dumont, L. F. C. (2019). Modelling the spatio-temporal bycatch dynamics in an estuarine small-scale shrimp trawl fishery. Fish. Res., 219, 105336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2019.105336

Rojo Vázquez, J. (1997). Selectividad y eficiencia de redes de enmalle en Bahía de Navidad, Jalisco, México (Unpublished master’s thesis), Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Mexico. http://www.repositoriodigital.ipn.mx//handle/123456789/14818

Saber, M. & Aly, W. (2023). Size selectivity of trammel nets applied in small-scale fisheries of Lake Nasser, Egypt. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res., 49(1), 113-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejar.2022.11.005

Saber, M., El-Ganainy, A., Shaaban, A., Osman, H. & Ahmed, A. (2022). Trammel net size selectivity and determination of a minimum legal size (MLS) for the haffara seabream, Rhabdosargus haffara in the Gulf of Suez. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res., 48(2), 137-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejar.2022.02.005

Sánchez-González, J. R. & Casals, F. (2022). Gillnet selectivity for three freshwater alien invasive fish species in a long-term monitoring scenario. Hydrobiology, 1(2), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrobiology1020017

Smith, B. J., Blackwell, B. G., Wuellner, M. R., Graeb, B. D. S. & Willis, D. W. (2017). Contact Selectivity for Four Fish Species Sampled with North American Standard Gill Nets. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag., 37(1), 149-161. https://doi.org/10.1080/02755947.2016.1254129

Sparre, P. & Venema, S. (1997). Introducción a la evaluación de recursos pesqueros tropicales – Parte 1: Manual. Doc. Tec. Pesca 306/1. Rome. FAO.

Tapia Varela, J. (2003). Propuesta tecnológica sobre pesca de enmalle para la captura comercial de tilapia, bagre y lobina en el embalse de Aguamilpa Yaniret. (Unpublished undergraduate thesis), Universidad Autónoma de Nayarit, Mexico. http://dspace.uan.mx:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/1991

Troadec, J. -P. (1984). Introducción a la ordenación pesquera: Su importancia, dificultades y métodos principales. Doc. Tec. Pesca, 224. Rome. FAO.

Wang, Z., Tang, H., Xu, L. & Zhang, J. (2022). A review on fishing gear in China: Selectivity and application. Aquacult. Fish., 7(4), 345-358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aaf.2022.02.006

Yu, M., Herrmann, B., Liu, C., Zhang, L. & Tang, Y. (2023). Effect of codend design and mesh size on the size selectivity and exploitation pattern of three commercial fish in stow net fishery of the Yellow Sea, China. Sustainability, 15(8), 6583. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086583

Zambrano, J., Macías, I., Urdánigo, E. & Mero, G. (2021). Pesca fantasma y su impacto en los ecosistemas marinos de San Mateo, Jaramijó y Crucita. Ing. Innov., 9(2), 2-22.

Zar, J. H. (2013). Biostatistical Analysis (5th ed.). U.S.A. Pearson Education, Inc.

1 Facultad Ciencias de la Vida y Tecnologías, Universidad Laica “Eloy Alfaro” de Manabí, Manta-Ecuador. klever.mendoza@uleam.edu.ec* ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9724-1139 jesus.briones@uleam.edu.ec ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6805-7706

2 Departamento de Biología, Facultad Ciencias del Mar y Ambientales, Universidad de Cádiz, 11510 Puerto Real, Cádiz-España.

3 Facultad de Ingeniería y Ciencias Aplicadas, Departamento de Procesos Químicos, Alimentos y Biotecnología, Universidad Técnica de Manabí, Portoviejo, Ecuador. jose.alio@utm.edu.ec ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2210-6802