|

REVISTA 95.2 Revista Relaciones Internacionales Julio-Diciembre de 2022 ISSN: 1018-0583 / e-ISSN: 2215-4582 doi: https://doi.org/10.15359/ri.95-2.6 |

|

|

|

The COVID-19 Pandemic and Haiti’s Changing Remittance Landscape La pandemia por COVID-19 y el cambiante panorama de las remesas en Haití Toni Cela1 ORCID: 0000-0003-4204-3968 Mário Fidalgo2 ORCID: 0000-0002-8616-3745 Louis Herns Marcelin3 ORCID: 0000-0002-9238-9695 |

||

Abstract

In 2020, analyses from multilateral institutions predicted that the COVID-19 pandemic would hamper remittance transfers to the Latin America and Caribbean region; yet they showed steady increases in 2020 and 2021. Haiti’s remittance economy has largely maintained its vitality, helping families weather multiple crises. Drawing on data from a study of the impact of COVID-19 on Haitian households and remittance data from Haiti’s Central Bank, this article examines Haiti’s changing remittance landscape, with particular attention paid to new migratory flows to Latin America that have emerged since the January 2010 earthquake. Considering the increase in migration to Brazil and Chile, among other countries, between 2010 and 2020, we ask, what role have remittances from South America played in Haitian households leading up to and during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Key Words: Brazil, Chile, COVID-19, Haiti, South-South migration, remittances.

Resumen

En 2020, los análisis de instituciones multilaterales predijeron que la pandemia por COVID-19 obstaculizaría las transferencias de remesas a la región de América Latina y el Caribe, no obstante, se experimentaron aumentos constantes en 2020 y 2021. La economía de remesas de Haití ha mantenido, en gran medida, su vitalidad, ayudando a las familias a superar múltiples crisis. A partir de obtenidos datos en un estudio sobre el impacto de la COVID-19 en los hogares haitianos y datos de remesas del Banco Central de Haití, este artículo examina el panorama cambiante de las remesas de Haití, con especial atención a los nuevos flujos migratorios hacia América Latina que han surgido desde el terremoto de enero de 2010. Así, se toma en cuenta el aumento de la migración haitiana a Brasil y Chile, entre otros países, durante 2010 y 2020, es que nos preguntamos: ¿Qué papel han jugado las remesas provenientes de América del Sur en los hogares haitianos antes y durante la pandemia por COVID-19?

Palabras clave: Brasil; Chile; COVID-19; Haití; Migración Sur-Sur; remesas.

Introduction: Haitian Migration to Latin America

Though Haitians have a history of migrating within Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) Region, South America as a choice destination for migrants began to surge after the 2010 earthquake (Fouron, 2020; Yates, 2021). In addition to the post-disaster context and favorable policies attracting Haitian migrants, since 2010, Haiti has been mired in multiple crises that have contributed to new migrant flows. In October 2010, United Nations officers introduced a cholera epidemic, which, to date, has claimed the lives of approximately 10,000 Haitians and infected over 800,000 (ASFC, 2019). Hurricane Tomas immediately followed the epidemic, claimed 35 lives, and injured dozens of victims in November 2010 (Marcelin & Cela, 2017a). In October 2016, Hurricane Matthew struck Haiti’s largely rural southern peninsula, claiming more than 500 lives, based on official though disputed counts, affecting over two million and causing an estimated USD 3 billion in damages (Marcelin & Cela, 2017a). Extensive damage to the agricultural sector, resulting in significant losses of livestock and crops, exacerbated food insecurity in this region of the country (Kiarnersi et al., 2021; Marcelin & Cela, 2017a).

By 2019, political unrest set in due to the PetroCaribe scandal, which revealed that more than half of the USD 4 billion loan for social programs provided to the Haitian government by Venezuela at a 1% interest was unaccounted for (INURED, 2020a). The PetroCaribe investigation concluded that Michel Martelly’s administration siphoned off these funds between 2009 and 2017, while also implicating his successor and sitting president at the time, Jovenel Moïse, for whom Martelly had served as a mentor (INURED, 2020a). Between September and December 2019, ongoing protests against the latter regime led to periodic road blockades that disrupted day-to-day affairs and the country’s supply chain, culminating in business and school closures across the nation (INURED, 2020a; Schüler, 2020). The PetroCaribe scandal appeared to abate in January 2020, and Haiti went into the COVID-19 lockdown from March to June 2020.

Throughout the pandemic, the country has experienced multiple parallel crises, including calls for President Moïse to step down, initially due to the PetroCaribe scandal and subsequently following a constitutional dispute regarding whether his mandate ended in February 2021 or February 2022 (Abi-Habib, 2021). Then, on July 7, 2021, Moïse was assassinated in his private residence in the early morning hours. The investigation into his assassination is ongoing. Barely over one month following the assassination, on August 14, 2021, a major earthquake, measuring 7.2 on the Richter scale, hit the southern peninsula of Haiti (Paz, 2021). Though the earthquake was stronger than the one in 2010, its epicenter in a largely rural area of Haiti caused significantly fewer causalities, claiming over 2,200 lives, and injuring almost 13,000 people (PAHO, 2021).

Throughout these crises, the government’s ability and will to represent the people’s interests and alleviate their suffering have been questioned as Haitian citizens leaned on one another for support (Cela .et al., 2022; Marcelin et al., 2016); they also turned, where possible, to international organizations for assistance, reflective of the historically broken social contract between the government and its people (Marcelin & Cela, 2017a; Marcelin & Cela, 2017b). Over time, disaster events, as well as social, political, and economic unrest, have increased the presence of international organizations vying to fill the void in social, health, economic, and disaster management services while earning Haiti the “NGO republic” title (Klarreich & Polman, 2012).

Prior to 2010, fewer than fifty Haitians were living in Brazil, most pursuing university studies. Following the January 2010 earthquake, Haitian migrants were steered toward Brazil, which needed to fill a labor shortage in preparation for the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics (Handerson, 2017; Schlabach, 2020). By mid-2013, at least 15,000 Haitian migrants lived in Brazil, signalling a new migratory era for both countries (Nieto, 2014). The choice of Brazil as a destination reflects its geopolitical influence, as this country has led the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) since 2004, comprising 45% of that military force (Audebert, 2017; Dias et al., 2020; Muira, 2020).

Between 2010 and 2013, the Brazilian government adopted resolutions to facilitate the migration of Haitian nationals to Brazil. By 2015, an estimated 95,500 Haitians were legally residing in Brazil (Observatório das migrações internacionais, 2019); obviously these numbers fail to account for undocumented Haitians. Between 2015 and 2016, Brazil’s economy experienced a severe downturn, with unemployment nearly doubling (Gallas & Palumba, 2019), compelling many Haitian migrants to seek opportunities elsewhere, particularly in Chile (Wejsa & Lesser, 2018). In 2019, Haitian laborers still comprised the largest migrant worker population in Brazil at 35.6%, and these statistics do not include migrants with irregular status or those working in the informal economy (Observatório das migrações internacionais, 2020).

In Chile, the Haitian population rose from less than 100 in the early 2000s to almost 180,000 in 2018, becoming 14.3% of its immigrant population (Ugarte Pfingsthorn, 2020). The immigration reforms Bachelet’s government adopted facilitated the influx of Haitians to Chile; these reforms included the provision of citizenship to the children of migrants—even those with irregular status—and the 2015 presidential instruction on migration policy and human rights (ibid). These reforms were notable in a country unaccustomed to hosting large populations of color or extracontinental migrants.

With the subsequent election of President Piñera, Chile’s center-right government revised its migration policy towards Haitian migrants, requiring tourist visas to be obtained in Haiti with employment contracts serving as a prerequisite for the visa or family reunification (Ziff & Preel-Dumas, 2018). The result was a 29% decrease in visas issued to Haitian migrants (Abdaladze, 2020) and a limited possibility for obtaining legal status. Subsequently, the Piñera government began offering “humanitarian flights” to migrants willing to return to Haiti. The policy was criticized as racist and as de facto deportation, yet by May 2019, more than 1,300 Haitian migrants had volunteered to return home, signing a declaration prohibiting re-entry for at least nine years (Laing & Ramos Miranda, 2018; Morley et al., 2021).

The rise in migration to South America is evidence that Haiti’s migration landscape has significantly changed in the post-earthquake period, rerouting migrants to and through new lands. Some borders have opened, others have closed, while host country reception has tempered migrant expectations and, under more challenging circumstances, dashed their hopes for a brighter future. Haitian migrants have had to adapt to shifting policies and realities in destination countries while maintaining their commitments to their homeland. Remittance transfers are, arguably, one of the greatest demonstrations of migrant commitment to family, friends, and loved ones, if not the easiest form of evidence policymakers and economists use to track their ongoing commitments (if not allegiance) to the homeland. Although the IOM has urged governments to rework their data frameworks to enhance data on the economic contributions of the diaspora, few standardized, official data sources (e.g., Balance-of-Payment statistics) exist on this key area in the region (IOM, 2020). The COVID-19 public health crisis provides a unique opportunity to examine the extent to which one’s duty to remit is tested during moments of crisis. This article, therefore, pays particular attention to two destinations that have seen a surge in migration from Haiti: Brazil and Chile.

Fortuitously, the rise in Haitian migration to South America corresponds with the emergence of literature on South-South migration (SSM) and remittances. Interest in these themes is evident from the literature published over the past decade, though it remains limited (Bhandari, 2016; Gallo, 2013; Kakhkharov et al., 2020; Kefale & Mohammed, 2018; Makina, 2013; Ratha & Shaw, 2007). Notably, focus on labor migrants in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East features prominently within the literature, while the LAC region remains largely absent. This article aims to fill that gap in knowledge by drawing on data collected in the context of a global crisis, specifically the COVID-19 pandemic. The article provides opportunities to examine migrant commitments to loved ones in the country of origin while drawing our attention to an understudied phenomenon. This phenomenon can inform the development of policies that have beneficial impacts for sending and host nations in the LAC region in times of crisis and during periods of relative normalcy.

Migrant Remittances in Times of Crisis: Fostering Dependence or Facilitating Survival?

According to International Monetary Fund (IMF) data, personal remittance volumes to Haiti exhibited a strong year-on-year uptrend in the decade following the 2010 earthquake, as measured by the percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), rising from approximately 11.7% in 2012 to 23.1% in 2020 (World Bank, 2021a). According to the World Bank (2022), remittances to Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) have outpaced the foreign direct investment (FDI) since 2016. and the official development assistance (ODA) has been recorded at three times for at least a decade. Since 2015, remittances to the LAC region have grown at least 6.7% per year, reaching an estimated 25.3% in 2021 (ibid). In 2023, remittances to the region are expected to reach an estimated USD 153 billion. According to the World Bank (2020), in 2018, remittances (USD 3.1 billion) significantly outpaced both ODA (USD 992 million) and FDI (USD 105 million). In 2020, FDI decreased further by 12% due to a decline in global economic activity, while remittances proved resilient, increasing by just under 1% globally that year.

In April 2020, the World Bank´s 35th Migration & Development Brief (2021c), which focuses on the impacts of COVID-19 on the global remittance economy, projected that remittances to the LAC region would fall by 19.3%; instead, in that year, it increased by 9.6% (World Bank 2020; 2021a; 2021b; 2021c). In fact, remittance flows to LMICs in the LAC region were among the most resilient in 2020 and 2021, growing 6.2% and 21.6%, respectively (World Bank, 2021c). According to the World Bank, these increases are related to several factors, including the US stimulus package and economic recovery in 2021; increases in transit and stranded migrants in the region, including Haitians, and an increase in remittances they receive; increases in remittance flows due to disaster events (e.g., hurricanes and earthquakes) in countries of origin; a depreciation of local currencies against the US dollar; and a marked increase in digital nomads working remotely from other countries in the region (World Bank, 2021c). Remittances to Haiti have remained relatively steady between 2019 and 2021, moderately decreasing from USD 3.2 billion to USD 3.1 billion during this period (World Bank, 2021b). Globally — as in the LAC region — remittances are projected to grow further in 2022 (World Bank, 2022).

While global remittance amounts continue to outpace ODA and FDI, their impacts have been greatly debated. Some argue that remittances do not foster economic development but encourage unnecessary consumption rather than providing necessities (Jahjah et al., 2003). In line with this pessimistic view, Clément’s (2011) microeconomic study of remittances in Tajikistan found their use unproductive at the household level (Clément, 2011). Yang (2011), however, argues that remittances used for consumption expenditures should be carefully evaluated — as they may be optimal for poor households with lower consumption levels. The more positive view of remittance spending suggests that they are critical to household survival and, in some cases, cover school fees, improve livelihoods through savings, and facilitate investments (Adams & Cuecuecha, 2010; Cardona Sosa & Medina, 2006). Further, remittances have been credited with helping poor households mitigate against and recover from disasters (Mohapatra et al., 2009).

Nowhere is this research more relevant than in the Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region, where the share of international migrants and remittance transfers sent home is significant compared to other regions (Ratha & Xu, 2008). Many studies have therefore sought to determine the impact of remittances in the LAC. In Guatemala, Adams & Cuecuecha (2010) found that remittances increased spending on education and housing. Mohapatra et al. (2009) report that remittances help families in disaster preparedness and recovery. In Haiti, Bredl (2011) found that remittances positively impacted educational outcomes among low-income families. However, Amuedo-Dorantes et al.’s (2010) research in Haiti found that although there were gains in human capital development, as in school attendance, the disruptive effects of family out-migration mitigated these gains. Despite these concerns, in the Haitian context, as elsewhere, remittances have proven critical in mitigating the effects of political, economic, and social upheaval, as well as disasters (INURED, 2020a).

The extant literature on the role of remittances in times of crisis in the homeland presupposes that international migrants are not directly affected by the same crisis, given their physical distance from it (Wendelbo et al., 2016; Yang & Choi, 2007). The COVID-19 pandemic and resultant economic shocks are clearly different, with global, cross-cutting impacts. Unlike localized crises (such as civil war, natural disasters, and famine, among others), the pandemic has affected every node in the transnational schema, including migrants in host nations and their families in the homeland.

In host nations, migrant populations have borne the brunt of the socioeconomic burdens of the pandemic (Freier, 2020; Martin & Ferris, 2017; Orozco, 2017). In the US, for example, employment fell by 9.8% for foreign-born workers between 2019 and 2020, compared to 5.4% for the native-born population. Data from the Brazilian Ministry of Labor show that the percentage of registered Haitian workers hired and terminated in the country was 3.3% and 3.5% in 2019 and 2020, respectively. However, this belies the fact that Haitians are among the lowest-paid migrant workers in Brazil’s formal economy (Observatório das migrações internacionais, 2020), and that they are overrepresented in the informal economy. Given their marginal status, often serving as agro-industrial, low-wage, and/or low-skilled laborers in the destination country, their vulnerability is likely to have been compounded by the pandemic. These factors certainly impact their ability to remit.

With few exceptions (Ratha & Shaw, 2007), studies of international remittances generally privilege transfers from countries in the Global North, often neglecting those from the Global South, despite the fact that by 2005, it was estimated that South-South Migration (SSM) accounted for almost half (47%) of all global migration, or at least 74 million migrants. More recent arguments suggest that by 2015, SSM “constitute[d] the bulk of international migration” (Short et al., 2020). Remittances have, in many ways, served as the cornerstone of studies on migration impacts on the economies and development of countries of origin, particularly in the Global South. However, shifts in migratory trends suggest a need for studies of remittances in the context of SSM. Ambrosius et al. (2020) contend that SSM flows account for one-third of remittances sent globally. Over the past decade, Brazil and Chile have emerged as prominent destinations for Haitians migrating within the Global South. However, to our knowledge, no notable studies on the impact of these new migration flows on Haiti’s remittance economy have been published.

Haiti provides a unique opportunity for further examination of the impact of SSM on the remittance economy, not only due to its history of migration within the Global South but also in light of shifting geopolitical realities and regional labor demands that have redirected post-earthquake migration toward South America. Brazil and Chile’s prominence in Haiti’s new migration landscape are key to understanding the nation’s remittance flows over the past decade, a period in which the country has experienced several major disaster events (ASFC, 2019; Marcelin & Cela, 2017a; Marcelin et al., 2016; Paz, 2021) and significant political, economic, and social upheaval (INURED, 2020b; Marcelin & Cela, 2017b).

This article draws on data collected during a study on the impact of COVID-19 on Haitian households implemented during the summer of 2020 and remittance data obtained from Haiti’s Central Bank in order to answer our central research question: What role have remittances from South America played in Haitian households leading up to and during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic? We begin by describing the methods employed in the study; then, we present the results from the Haiti Central Bank data and COVID-19 study, followed by a brief discussion and conclusion. The data reveal that Haitian migrant commitments to the homeland — as evidenced by remittance transfers — are vital to household survival and remain constant, particularly during times of crisis.

This article draws on several sources of data: central bank remittance data and a mixed-methods study on the impact of COVID-19 on families in urban and rural Haiti conducted by the Interuniversity Institute for Research and Development (INURED) between July and August 2020. Funded by the UKRI Global Challenges Research Fund, the study included a survey of 511 households, five focus groups, 25 ethnographic interviews, observations, and social mapping. A three-stage cluster sampling design was implemented in 15 major localities in five administrative departments of Haiti: Ouest, Grand-Anse, Centre, Artibonite, and Nord, selected randomly with probability proportionate to size. The sampling frame was initially compiled by the Haitian Institute of Statistics and Informatics (IHSI) and updated in 2015 to reflect the rapid transformation of cities and towns following the 2010 earthquake. Within the cities and towns are IHSI-defined segments known as Sections d’Enumérations (SDEs), the study’s primary sampling units (PSUs). The total of PSUs in the five metropolitan areas constitute the frame from which SDEs were selected.

Remittance data from Haiti’s central bank, Banque de la République d’Haïti (BRH), were obtained from the Institut Haïtien de Politiques Publiques (Haitian Institute for Public Policy) and analyzed to provide a macro-level snapshot of the impact of COVID-19 on Haiti’s remittance economy. Haiti’s central bank collected inbound and outbound bilateral remittances data from all local banks and financial transfer services companies in Haiti to produce the national Balance-of-Payment (BOP) statistics (following the guidance outlined in the Handbook for Improving the Production and Use of Migration Data for Development4). The data document only the flow of formal transfers through formal institutions; informal transfers via individuals and family networks are not captured by the central bank. According to Irving et al. (2010)5, the underreporting of informal transfers by countries’ central banks may have reached as much as 50% in the published official data. Due to low literacy rates, the study’s objectives were explained orally in Haitian Creole, the most spoken language. INURED’s U.S. Department of Health and Human Services-approved Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the study protocol (IRB# MD-S-020-/1-2019-233).

Haiti’s 2010-2020 Remittance Economy: Central Bank Data

Publicly available data on remittance transfer volumes to Haiti is problematic for four reasons: 1) the IMF and the World Bank only provide quarterly estimates; 2) official BOP statistics6 are known to underestimate remittances; 3) the most recent nationwide household survey7 contains indicators on migration and remittances but does not fully capture post-earthquake migratory destinations that have emerged over the decade; and 4) such data fail to account for informal, though critical, transfer channels.

To overcome these challenges, the research team acquired access to monthly remittance transfer data covering a specific time within the overall study period: from October 2017 to August 2020. Although the series is small (n=35 months), it contains data for the period leading up to, during, and immediately following the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, it disaggregates remittance amounts by source country. Due to the sample size, the analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on households in Haiti is limited and not generalizable; however, it does provide insights that may help orient future studies of migration and migrant commitments to the origin country in times of crisis.

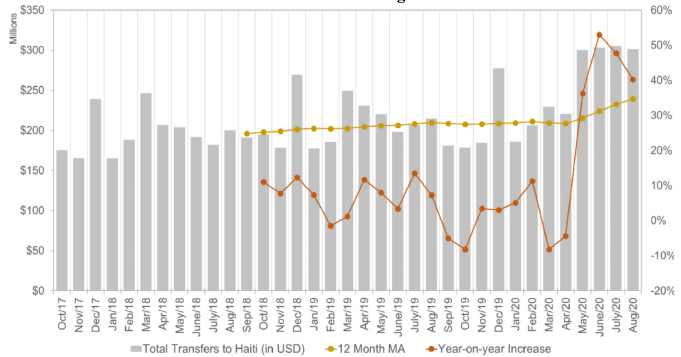

According to BRH data, between October 2017 and August 2020, remittance transfers were relatively constant, with March 2019 and December 2019 serving as the peak transfer months and a notable decline in March 2020 when the pandemic was officially declared in Haiti. Following a dip in transfers in April 2020, remittance volumes to Haiti peaked from May to August 2020, recording the highest amounts transferred during the 35-month period (Figure 1). The decline in remittances during the pandemic was not significant, as 2019 had already seen sharp declines due to the ongoing political crisis in Haiti referred to as Peyi Lok8. During the five months that exhibited a negative year-on-year change in the series, October 2019 and March 2020 were the lowest, at -8.2% for each month, compared to the same month of the previous year. By May 2020, year-on-year increases were positive and in the double digits until the last month of available data (August 2020), with June 2020 representing an increase of more than 50% over June 2019.

Figure 1: Total Remittance Transfers to Haiti (in USD): Year-on-Year Change between October 2017 and August 2020

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Banque de la République d’Haïti data.

Figure 1 shows the six-month simple moving average (SMA) as an indicator of the general upward trend. From May 2019 to November 2019, all monthly remittance volumes to Haiti were below the six-month SMA, indicating a weakening trend through 2019. Thus, when examining remittance flows to Haiti during the first phase of the pandemic, it is essential to acknowledge the sharp decline in transfers in the latter part of 2019. Except for January, all months in 2020 exhibit a higher transfer volume than the six-month SMA, and a significant upward trend is evident, especially when considering the months between May 2020 and August 2020.

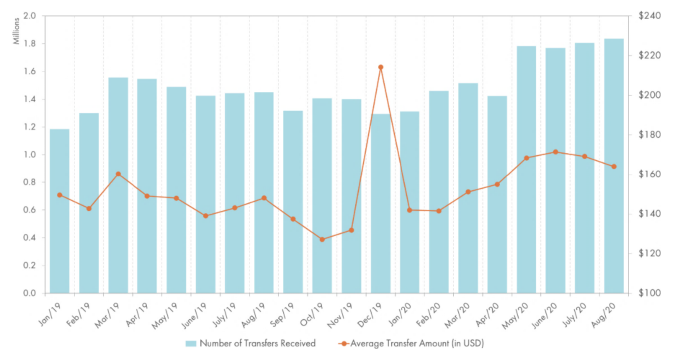

Figure 2: Number of Transfers Received & Average Transfer Amount (in USD): October 2017 to August 2020

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Banque de la République d’Haïti data.

Figure 2 shows the total number of transfers received and their USD average amount. In April 2020, while the total number of transfers decreased significantly, the average transfer amount increased approximately 2.5 percent from USD 151.17 to USD 154.95. COVID-19-related public health measures (e.g., lockdowns, stay-at-home orders, business closures) adopted in major sending countries, particularly the US and Canada, seemingly disrupted money transfer services. Therefore, migrants may have made up for these disruptions by sending larger amounts. A stepwise increase in average transfer amounts occurred in the first six months of 2020, from USD 141.93 in January to USD 171.43 in June. With the maximum in December 2019 reaching USD 214.24, however, it seems that the recovery in remittance volumes was largely sustained by an increase in number of transfers rather than their amount. The extent of the recovery in terms of the total number of transfers is remarkable, indicating the engagement of remittance senders during the pandemic.

Comparing Remittances to Haiti from the Global North with those from the Global South

The study of COVID-19’s impact on households in Haiti allows for a unique comparison of differential remittance flows from countries in the Global North and the Global South. Firstly, the central bank data are disaggregated by source country, and secondly, the study sample contains data on the country of migration (source country), remittance amounts, and basic spending indicators, as well as other relevant socio-demographic information. Here we provide the results of the descriptive analysis of both datasets, differentiating between source countries in the Global North and Global South. We pay special attention to the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, providing a primary analysis of the impacts of the global crisis on remittance flows to Haiti.

For the study period, remittance inflows from countries in the Global North differed greatly from those of the Global South. Previous work (OECD & INURED, 2017; Orozco, 2006) has highlighted the importance of remittances from the Global North, particularly the US, where most Haitian migrants reside. To our knowledge, there has been no prior research in Haiti explicitly analyzing differences in remittance flows and impacts from countries in the Global South. Further, as many studies have relied on the Haiti Living Conditions Surveys from 2001 or 2012 (e.g., Jadotte, 2009; Justesen & Verner, 2007), they do not capture contemporary surges of post-earthquake migration to the Global South. The present study contributes to the growing literature on SSM and remittances by outlining differences in household-level outcomes by country of destination.

Banque de la République d’Haïti Remittance Data

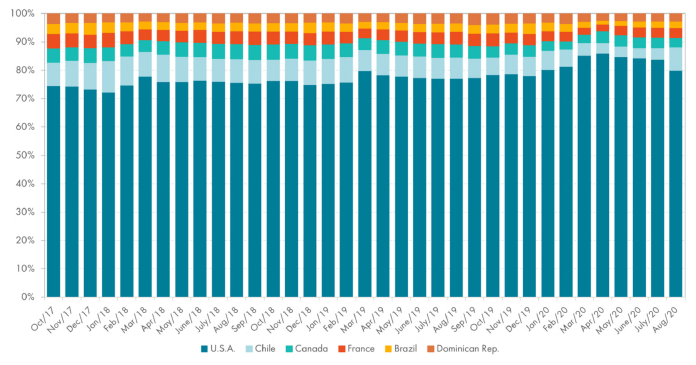

Monthly remittance transfer data by country between October 2017 and August 2020 suggest that although the US still accounts for between 70% and 84% of all remittances to Haiti (see Figure 3), more recent destination countries such as Brazil and Chile have emerged as newer, yet still critical, remittance sources. For example, in August 2020, Chile accounted for 8% (USD 22 million) of total remittance volumes to Haiti, almost equivalent to the total combined contributions of Canada, France, and Brazil.

Remittances from countries in the Global North, including the US, Canada, and France, tend to peak in March in the time series (See Figure 3). In 2020, however, this peak occurred in April 2020. Destination countries in the Global North accounted for 89% of remittance flows as per the central bank data in April 2020. The US alone contributed USD 238 million, amounting to 83% of remittance flows to Haiti that month, despite measures adopted to curb the spread of COVID-19, such as closing businesses and schools and restricting population movements. These measures were not equally adopted for major remitting countries in South America, including Brazil and Chile.

Figure 3: Proportion of Remittance Transfers to Haiti (%) by Top Six Source Countries: October 2017 to August 2020

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Banque de la République d’Haïti data.

Although Brazil was the first South American country to emerge as a major migration destination for Haitians, remittance volumes from Brazil were lower than those from Chile in all 35 months of the BRH time series. On average, remittance inflows from Chile were 165% greater than those from Brazil, while transfers from Brazil appeared more stable than those from Chile. Remittances from Chile exhibit a general downtrend as 20 out of 23 months exhibited year-on-year decreases and greater variance, while remittances from Brazil remained steadier, with only 10 out of 23 months exhibiting decreases. Furthermore, during the peak of the first wave of the pandemic, from March 2020 to May 2020, when Haiti instituted various lockdown policies, including closing its airports and borders, remittance volumes from Chile experienced much larger decreases than those from Brazil as year-on-year changes. The recovery in Chile was only seen in August 2020, while Brazil showed year-on-year increases between June 2020 and August 2020. This may indicate Chile’s waning status as a destination country for Haitian migrants. Moreover, we hypothesize that as Brazil emerged first, individuals’ time in a country may be longer on average, allowing for more integration and, thus, greater financial security than that experienced by migrants in Chile9.

The Haitian central bank dataset is also not without its limitations. One limitation is the inability to capture remittance transfers made through informal channels, such as person-to-person delivery or intermediary networks. In this regard, household-level data may provide important insights into informal exchange patterns in Haiti’s remittance economy.

COVID-19 Study Data

The survey of 511 households in five administrative departments of Haiti comprised 361 (71%) female- and 148 (29%) male-headed households. More than half (51%, 259) of all respondents were between 32 and 45 years of age, 24% (124) were aged 18 to 31, while 21% (106) were between 46 and 59 years old, and 4% (22) 60 years or older. This is consistent with Haiti’s youthful demographic profile and with World Bank (2019) estimates that 62% of the Haitian population is between the ages of 15 and 64. Eighty percent (410) of households were urban, and 20% (101) were rural. More than half (56%, or 286) had between four and six family members living in the home; 19% (97) had one to three members; 19% (98) between seven and nine members; and 6% (30) 10 or more. Sixty-nine percent (353) of participants reported having one to three offspring, 22% (114) four to six; 4% (20) between seven and nine, and 1% (7) 10 or more children. Before the pandemic, 46% of households (236) were engaged in petty commerce, 26% (135) were engaged in wage labor, 17% (85) were entrepreneurs, 6% (33) were inactive but not seeking formal employment, and 4% (21) were unemployed.

More than half (52%, or 265) of all households reported having no family or close friends living outside of Haiti, 27% (137) had only a close friend abroad, and 21% (109) were migrant households, defined here as having a family member living abroad. Among migrant households, 64% (70 of 109) reported only having a family member living abroad, and the remaining 36% had at least one family member and a close friend living abroad. Among non-migrant households, more than one-third (34%, or 137) had only a close friend living abroad.

A significant number of study respondents indicated having some university education or having completed all university-level studies at 7% (34) and 8% (43), respectively10. Over one-third of participants (39%, or 197) reported having some secondary school education, 16% (83) cited having completed secondary school, and 6% (29) reported no formal schooling. For migrant households in the sample (n=109), the proportions of higher education were slightly greater than the general sample at 10% (11) for some university education and 9% (10) for all completed university-level studies. Migrant households with close friends abroad reported higher education levels on average than all other categories, with just under one-quarter (23%, or 9 of 39) having completed some or all university-level studies. Almost one-fifth (17%, or 27 of 137) of migrant households with no close friends abroad had completed some or all university studies. Non-migrant households were among the least educated, with almost 10% (25 of 264) having no formal schooling. It has been shown that migrants from Haiti are “positively selected” when it comes to socio-economic status and exhibit a greater propensity to migrate as per capita income and educational attainment increase (Orozco, 2006)11.

Households with migrants in the Global North exhibit higher levels of educational attainment on average than those with migrants in the Global South. Slightly more than one-quarter (26%, or 14 out of 54) of households with migrants in the Global North reported having completed some or all university-level studies, whereas only 13% (7 out of 55) of households with migrants in South America reported the same. In addition, 12 household heads (24%) with migrants in South America reported having had no formal schooling or some primary school. This is the case for only 3 (6%) heads of households with migrants in the Global North, all of whom reported at least some primary school. Notably, there were no cases of no formal schooling for household heads with migrants in the Global North. These findings align with previous works (INURED, 2020b; Schlabach, 2020) showing the proliferation of unskilled and semi-skilled laborers migrating to Brazil, recruited as workforce for the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympic Games.

These statistics show the importance of migration capital in Haiti for migrant and non-migrant households. Furthermore, households with more than one migrant abroad (one household reported having as many as eight) proportionally received higher numbers of remittances. Eighty-six percent (86%, or 31 of 36) of households with two or more migrants abroad reported receiving remittances in the previous 24 months. This figure jumps to 95% (18 out of 19) when considering households with three or more migrants.

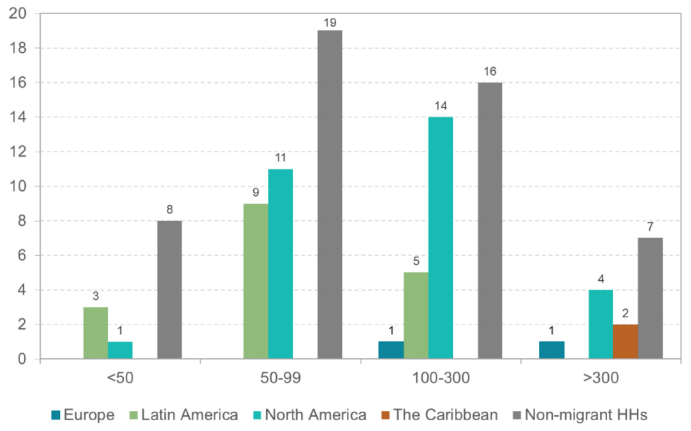

Consistent with the analysis of Haiti’s central bank data, we find stark differences in remittance receipt per North or South migration corridor. Eighty-three percent (83%) of households with migrants in the Global North reported receiving remittances in the previous 24 months, while the proportion for those in the Global South was only 64%. When asked about the amounts of remittance transfers received between March 2020 and May 2020, respondents with migrants in the Global North reported higher amounts than those with migrants in the Global South. Well over half (59%) of respondents associated with a migrant(s) in the Global North reported receiving more than USD 100 as compared to 37% with a migrant(s) in the Global South. Forty-one percent (41%) of non-migrant households reported receiving more than USD 100 from a close friend between March 2020 and May 2020. More than twice as many (59, or 69%) households with close friends living abroad that reported receiving remittances within 24 months of the survey had migrants in countries of the Global North versus 26 (31%) with close friends sending remittances from the Global South. Notably, 54 of the 59 households receiving remittances from the Global North were linked to the United States.

For remittance transfer amounts below USD 100, proportions for households with migrants in the Global South were almost double (63%) that of the Global North (35%), indicating that households with migrants in the Global South received lower amounts. According to this indicator, even non-migrant households receiving remittances from close friends in the Global North fared better than migrant households with family members in the Global South. The vast differences in remittance transfer amounts received from the Global North and South at the household level are consistent with Haiti’s central bank data reporting.

The vast majority (88%, or 94 of 107) of COVID-19-related remittance disruptions were linked to livelihood activities such as employment loss or disruption. Eleven percent of respondents cited transfer service interruptions either in Haiti or the source country as the reason for disruptions. The extent or duration of these disruptions is unknown. However, in households that had received remittance transfers within 24 months of the survey, only 59% (85 of 145) reported receiving transfers early on after the official declaration of a pandemic and lockdown period between March 2020 and May 2020 in Haiti. As expected, of these households, there appeared to be a positive relationship between the amount received and the number of migrants a household had abroad, including close friends. This may suggest that, in times of crisis, households not typically receiving remittance transfers may activate migrant networks that are otherwise inactive. Interestingly, a few (8) households reported sending, rather than receiving, remittances during this period. Among these households, 75% (6) had migrants in the Global South: 2 in Brazil, 2 in Chile, and 1 in Ecuador.

Figure 4: Reported Remittance Amounts between March and May 2020 by Migration Corridor Region

Source: Authors’ calculations based on INURED household survey data.

Out of 109 migrant households, there were nearly equal distributions of family members in the Global North (54) and South (55). More than three-quarters (78%, or 43 of 55) of migrants in the Global South were in South America, overwhelmingly Brazil and Chile, accurately reflecting changes in Haitian migration destinations in the post-2010 earthquake period. Of the 39 migrant households with close friends abroad, households with migrants in South America tended to have more close friends in the US and Canada than in these regions. This may indicate recent trends in onward migration from South America to the United States12,13. Of the 19 households that had migrants in continental North America and a close friend abroad, 13 reported the close friend living in North America and six in the Caribbean. Of the 14 households with migrants in South America, six had a close friend in the US or Canada, four in the Caribbean, and the remaining four in South America. Thus, even for migrant households participating in the new SSM routes, the North American and Caribbean corridors remain a crucial dimension to their transnational composition.

Rural migrant households tended to migrate to destination countries in the Global South, particularly Brazil and Chile. Of the 24 rural migrant households, 15 (63%) were in South America, and six (25%) were in continental North America. In contrast, of the 85 urban migrant households, more than half (52%, or 44) were in continental North America and only one-third (28) in South America. These data are consistent with historic migration trends in Haiti in which those from rural parts of the country migrate within the Global South, whereas urban dwellers tend to migrate to the Global North14. In an examination of household transnational status vis-à-vis gender, there was a higher proportion of female-headed households with migrants in the Global South (42 out of 55; 76%), as compared to the Global North (30 out of 50; 56%). It is known that most Haitian migrants in Brazil and Chile are male, which may contribute to these differences.

Regarding migration within the Caribbean, 8 out of 11 households had a migrant in the Dominican Republic (DR) at the time of the survey. The other three households reported having a migrant in Turks and Caicos (1) and the Bahamas (2), and all three reported receiving remittances. Only one-quarter (2 of 8) of households with a family member in the DR reported receiving remittances; both households were urban. As previously mentioned, two households with migrants in the Caribbean showed extreme values for some key indicators, suggesting that they may not be representative. Moreover, all households with migrants in the Caribbean were female-headed households, reflecting the intense circulation of male laborers across this corridor.

When comparing the remittance spending patterns of migrant households with those of non-migrant households, we found higher proportions reportedly spent on food, health, rent, land, and education in the former (see Table I). A significantly higher proportion of migrant households responded positively to these indicators than non-migrant households, particularly the education variable. The double-digit differences in proportions between migrant and non-migrant households with respect to expenditures on schooling (-25%), rent (-18%), and health (-14%) could indicate that in households with migrants as opposed to friends living aboard, there is more stability and consistency in remittance reception which translates into a more productive use of remittance transfers. There were stark differences in remittance spending on health along gender lines; 67% (32 of 48) of women compared to only 31% of men (8 of 26) reported directing these resources toward health expenditures.

Table I: Proportion of Positive (“Yes”) Responses for Expenditure Areas for Migrant vs. Non-migrant Households

|

Consumption area |

Migrant |

Non-migrant |

Difference |

|

Food |

95% |

87% |

-8% |

|

School |

62% |

37% |

-25% |

|

Health |

54% |

40% |

-14% |

|

Rent |

33% |

15% |

-18% |

|

Land |

8% |

3% |

-5% |

Source: Authors’ calculations based on INURED household survey data.

Across some areas of spending, Global North migrant households exhibited similar reported proportions as those migrant households with family members in the Global South. For example, 30 out of 31 (97%) households with migrants in the Global South reported spending remittances on food compared to 40 out of 43 (93%) households with migrants in the Global North. Reported proportions were also similar for education expenditures, although a greater proportion, 28 out of 43 (65%), of Global North transfer recipients paid for schooling versus 18 out of 31 (58%) for the Global South. The greatest differences were in health and rent expenditures. While a greater proportion of Global South migrant households reported spending on health, there was an equally high difference in the other direction when looking at spending on rent. Just under half (20 out of 43) of Global North migrant households reported spending on health, while almost two-thirds (20 out of 31) of Global South migrant households did the same, a net difference of 18%. This supports the assertion that female-headed households are more likely to spend on health, as more than three-quarters (76%, or 42 out of 55) of households with migrants in the Global South are headed by women. This is compared to 30 out of 54 (or 55%) of Global North households that are female headed. Forty percent (17 out of 42) of Global North migrant households reported using remittances to cover rent expenses, as compared with fewer than one-quarter (7 out of 31) of Global South migrant households.

When cross-tabulating the proportion of positive answers to the indicator for child #1 by transnational status, there was a higher proportion of remittances supporting educational expenditures from migrants in the Global North (49%) than the Global South (37%). As private school tuition is paid periodically throughout the year, this may partially explain the greater frequency and larger transfer amounts sent from migrants in the Global North, as they may have made explicit commitments to cover school tuition costs. However, financial support for school tuition received from the Global South is significant, and over one-third of migrants have made similar commitments.

Over the past two decades, the body of literature on SSM has expanded, drawing increasing attention to the impact on remittance economies in the Global South (Ambrosius et al., 2020; Ratha & Shaw, 2007; Short et al., 2020). However, there remains a paucity of literature on the impact of this phenomenon on nations in the LAC region. For migrant-sending and remittance-dependent nations such as Haiti, examining the impact of these new migration corridors on families and communities are critical as both sending and receiving nations grapple with finding a migration development nexus (Faist & Fauser, 2011; Van Hear & Sørensen, 2015).

As the data demonstrate, despite the rise in migration flows from Haiti to South America, migrants in countries in the Global North still account for the greater proportion of remittances sent to Haiti. However, countries in South America are emerging as significant sources of remittance transfers. During the BRH data period, Chile was demonstrably a significant source of financial support to Haitian families in terms of the quantity of transfers remitted, while transfers from Brazil have been more durable and consistent over time.

International migration is a strategy that has served as a form of capital that supports, sustains, and/or facilitates the survival of households in Haiti, as it does in other sending nations. Clemens & Ogden (2019) have urged a new, more productive conceptualization of remittances as returns on (the migration) investment. Admittedly, remittance transfers are among the most obvious, though not sole, benefits drawn from international migration. These transfers are critical in helping families absorb the shocks experienced during political, social, economic, and/or environmental crises, all of which Haiti continues to experience.

Haiti’s transition to democracy since the fall of the Duvalier regime has been wrought with political crises (INURED, 2020b; Marcelin & Cela, 2017b) crystallized by the July 2021 assassination of its President Jovenel Moïse. Over the past two decades, Haiti has experienced almost a dozen disaster events (ASFC, 2019; Shultz et al., 2016), its most recent devastating August 2021 earthquake (Paz, 2021). Serving as the backdrop to political instability, social unrest, disaster events, and the pandemic is an economic crisis dating back to 2018 when IMF fuel subsidies were withdrawn, resulting in rising fuel costs (INURED, 2020a). We contend that remittance transfers determine many households’ ability to withstand such precarious conditions by contributing to food, health, and education expenditures. This is clear from the sample data, where most households reported spending remittances on food, irrespective of migrant destination in the Global North or South. The high proportions of responses to health and education expenditures also support this fact.

The obligation to remit extends beyond one’s immediate family members or former household members to include close friends. Though remitting practices for the latter group are by no means constant, almost half of non-migrant households received remittance transfers from close friends in the months preceding the survey. In fact, the COVID-19 crisis emerged within two months of the reopening of most of Haiti’s businesses, a period during which businesses and institutions were effectively shut down by Peyi Lòk (INURED, 2020b). Given the low socio-economic status of study participants and the majority of the Haitian population, it can be surmised that these periods corresponded with reductions in earnings or suspension of employment. The central bank and study data must be examined in this light, as a period of extended and multiple crises in Haiti, neither of which have fully abated.

To understand the importance of remittances for Haitian families, we must also consider the nation’s vulnerability to disaster. Haiti’s experiences of, and vulnerability to, disaster events are exacerbated by an absence of robust mitigation efforts and disaster governance plans (Cela et al., 2022; Marcelin et al., 2016). In fact, Kianersi et al. (2021) contend that Haitians have faced prolonged periods (more than one year) of food insecurity and that the context requires that we characterize their vulnerability as “long-term post-disaster food insecurity” (p. 2). Consumption patterns of remittance-receiving households show that food is the most prominent expenditure associated with remittance transfers for both migrant and non-migrant households. Although many researchers would consider this spending “non-productive,” we assert that this is clearly an important, life-sustaining expenditure in a country with extreme poverty and food insecurity.

Even among non-migrant households with close friends abroad, the data reveal that consumption patterns, in many respects, mirror those of migrant households despite their infrequency and lower transfer amounts. Interestingly, whereas migrant households report education as the second most common expenditure, non-migrant households report health. As non-migrant households receive irregular and smaller transfer amounts, investments in education would not be sustainable over time. Migrant parents with a child(ren) in the homeland may prove to be more reliable sources of remittances for educational purposes than, say, extended family members. Therefore, once education is eliminated from the category of expenditures, both migrant and non-migrant households use these resources to cover food and health expenditures in that order. This suggests that remittances are used to cover basic necessities and, in microeconomic terms, may serve as a “consumption smoothing mechanism” (Perakis, 2011).

It is important to note the gendered nature of recipient expenditures, which suggests that women are more inclined than men to use these resources on health-related expenditures. These findings are consistent with prior studies suggesting that women recipients are more likely to invest in human capital (Guzman et al., 2008) than their male counterparts, who tend to spend more on consumption (OIM, 2015; Lopez-Ekra et al., 2011).

One can surmise that the ability to purchase food, access healthcare (particularly in the aftermath of disaster events), and cover school fees are critical in absorbing the economic shocks resulting from various forms of crisis, particularly in the absence of government relief and support. These findings expand our understanding of the rising importance of the remitting practices of Haitian migrants in the LAC region. These data elucidate the reliance of many Haitian households on resources from Brazil and Chile during a period in which Haiti has experienced extreme tumult that may continue into the foreseeable future.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Haiti experienced its greatest remittance disruptions between April 2020 and May 2020, corresponding with the nation’s lockdown period. However, the projected larger scale disruptions to Haiti’s remittance economy did not come to fruition, and transfer amounts bounced back within a few months. Bragg et al. (2017) have shown that in the immediate aftermath of crises, an increase is generally observed in remittance transfers received only during the quarter in which the disaster occurred. The data suggest that the level of solidarity and commitment to supporting family and close acquaintances in the origin country remained high, even in the context of a global pandemic. This suggests that Haitians living abroad provided timely support to ensure the survival of family and close friends in Haiti immediately following the outbreak of the pandemic.

Remittance transfers remain an important resource for urban and rural families in Haiti. In times of social unrest, political turmoil, economic instability, and disaster, Haitian families rely on the commitments of family members and friends living abroad for financial support to prepare for and absorb the shocks of crisis events. Even in the context of a global pandemic that has affected both migrants and migrant households in the country of origin, Haiti’s remittance economy has maintained its vitality irrespective of the migrant destination.

Since 2010, South America has emerged as a destination of choice for Haitian migrants, many of whom now call Brazil or Chile their home. As they set roots on the South American continent, they maintain connections to their homeland, in part, through remitting practices. As the data reveal, these connections remain vital for Haitian families and communities that rely on the Global North and South resources to meet their basic needs, particularly in times of crisis. Given the significant rise in South-South Migration over the past decade, future studies of Haiti’s remittance economy should focus on comparative amounts, volumes, expenditure patterns, and the differential impacts of transfers received from the Global North and South through formal and informal channels. Such an examination across sectors such as education and health will help determine the differential impacts of transfers on Haitian households and assess whether Haitian migration within the Global South is generally beneficial or detrimental to those remaining in the home country and perhaps provide more insights into migrant decisions to migrate as we as their choice of destination.

However, we must also acknowledge that while some Haitian migrants have made the South American continent, their adopted home, others have engaged in onward migration after months or years of living in the region (INURED, 2020b; Kahn, 2021; Yates, 2021). Therefore, it will be fundamental to conduct studies that examine potential bidirectional flows of remittance transfers between migrants and migrant households in the origin country to account for homeland support of migratory journeys. These data will help elucidate the value placed on migration as a long-term strategy for the survival of Haitian families in the homeland.

This work has been funded by the UKRI Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) [Grant Reference: ES/S007415/1]. We wish to thank April Mann for her assistance with the editing of this manuscript.

Abdaladze N. (2020). Haitians make long continental transit in hope for a better future. Cronkite News, Special Reports, pp. 1. Retrieved from: https://cronkitenews.azpbs.org/2020/07/20/haitians-continental-transit/.

Abi-Habib, M. (2021). Haiti braces for unrest as a defiant President refuses to step down.

New York Times, Americas, pp. 1. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/07/world/americas/haiti-protests-President-Jovenel-Mois.html.

Adams, R. H. & Cuecuecha, A. (2010). Remittances, household expenditure and investment in Guatemala. World Development, 38(11), 1626-1641.

Ambrosius, C., Fritz, B. & Stiegler, U. (2020). Remittances. In O. Kaltmeier, A. Tittor, D. Hawkins & E. Rohland (Ed.). The Routledge Handbook to the Political Economy and Governance of the Americas (1st ed., pp. 194-199). Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., Georges, A. & Pozo, S. (2010). Migration, Remittances, and Children’s Schooling in Haiti. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 630(1): 224–244. doi: 10.1177/0002716210368112.

Audebert, C. (2017). The recent geodynamics of Haitian migration in the Americas: Refugees or economic migrants? Revista Brasileira de Estudos de Populacao. 34(1): 55-71.

Avocats sans Frontieres Canada (ASFC). (2019). Meeting the needs of victims of cholera in Haiti. Retrieved from: http://www.inured.org/uploads/2/5/2/6/25266591/cholera_study_summary_report_english.pdf.

Bhandari, P. (2016). Remittance received by households of Western Chitwan Valley, Nepal: Does migrant’s destination make a difference? Dhaulagiri Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 10(1): 1–36. doi: 10.3126/dsaj.v10i0.15879.

Bragg, C., Gibson, G., King, H., Lefler, A. & Ntoubandi, F. (2017). Remittances as aid following major sudden-onset natural disasters. Disasters, 42(1): 3–18. doi: 10.1111/disa.12229.

Bredl, S. (2011). Migration, remittances, and educational outcomes: The case of Haiti, Discussion Paper, No. 44, Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen, Zentrum für Internationale Entwicklungs- und Umweltforschung (ZEU).

Cardon-Sosa, L., Medina, C. (2006). Migration as a safety net and effects of remittances on household consumption: The case of Colombia, Borradores de Economia, n° 414, Bogotá: Banco de la Republica de Colombia.

Cela, T., Marcelin, L. H., Fleurantin, N. L. & Jean-Louis, S. (2022). Emergency health in the aftermath of disasters: A post-Hurricane Matthew outbreak in rural Haiti. Disaster Prevention and Mitigation.

Clemens, M. A. & Ogden, T. N. (2019). Migration and household finances: How a different framing can improve thinking about migration. Development Policy Review, 38(1): 3-27. doi: 10.1111/dpr.12471.

Clément, M. (2011). Remittances and household expenditure patterns in Tajikistan: A propensity score matching analysis. Asia Development Review, 28(2): 58–87. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2001145.

Edwidge, D. (2021). The assassination of Haiti’s president. The New Yorker, News Desk, pp. 1. Retrieved from: https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/the-assassination-of-haitis-president.

Dias, G., Jarochinski-Silva, J. & da Silva, S. A. (2020). Travellers of the Caribbean: Positioning Brasília in Haitian migration routes through Latin America. Vibrant, 17(1): 1-19.

Faist, T. & Fauser, M. (2011). The migration–development nexus: Toward a transnational perspective. In Faist T., Fauser M., Kivisto P. (Ed.). The migration-development nexus. Migration, diasporas, and citizenship Series. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fouron, G. E. (2020). Haiti’s painful evolution from promised land to migrant-sending nation. Migration Policy Institute, Migration Information Source, pp. 1. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/haiti-painful-evolution-promised-land-migrant-sending-nation.

Freier, L. F. (2020). COVID-19 and rethinking the need for legal pathways to mobility: Taking human security seriously. International Organization for Migration Bookstore. Retrieved from https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/rethinking-the-need-for-legal.pdf.

Gallas, D., Palumba, D. (2019). What’s gone wrong with Brazil’s economy? BBC, Business, pp. 1. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-48386415.

Gallo, E. (2013). Migrants and their money are not all the same: Migration, remittances and family morality in rural South India. Migration Letters, 10(1): 33-46.

Guzman, J. C., Morrison, A. R. & Sjöblom, M. (2008). The impact of remittances and gender on household expenditure patterns: evidence from Ghana. In A. Morrisson (Ed.). The International Migration of Women (1st ed., pp 125-152). Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Handerson, J. (2017). A historicidade da (e)migração internacional Haitiana. In B. Feldman-Bianco, L. Cavalcanti, L. Araujo & E. Brasil (1st ed.). PERIPLOS: Revista Investigación sobre Migraciones: Buenos Aires: 7-26.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). (2020). Contributions and Counting: Guidance on Measuring the Economic Impact of your Diaspora beyond Remittances. Geneva, CH: IOM Press.

Interuniversity Institute for Research and Development (INURED). (2020a). The Impact of COVID-19 on families in urban and rural Haiti (1st ed.). Port-au-Prince, Haiti: INURED.

Interuniversity Institute for Research and Development (INURED). (2020b). Post-Earthquake migration to Latin America: Working Paper. (1st ed.). Port-au-Prince, Haiti: INURED.

Jadotte, E. (2009). International migration, remittances and labour supply: The case of the Republic of Haiti, WIDER Research Paper, No. 2009/28. Helsinki, Finland: The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER).

Jahjah, S., Chami, R., & Fullenkamp, C. (2003). Are immigrant remittance flows a source for capital development? IMF Working Paper. Washington. D.C.: International Monetary Fund.

Justesen, M., & Verner, D. (2007). Factors Impacting Youth Development in Haiti. Policy Research Working Papers. Washington, D.C.: World Bank. doi: 10.1596/1813-9450-4110.

Kahn, C. (2021). On Mexico’s southern border, the latest migration surge is Haitian. NPR, News, pp. 1. Retrieved from: https://www.npr.org/2021/12/18/1065135970/on-mexicos-southern-border-the-latest-migration-surge-is-haitian.

Kakhkharov, J., Ahunov, M. & Parpiev, Z. (2020). South-South Migration: Remittances of labour migrants and household expenditures in Uzbekistan. International Migration, 59(5): 38-58. doi: d10.1111/imig.12792.

Kefale, A. & Mohammed, Z. (2018). Migration, remittances and household socioeconomic well-being: The case of Ethiopian labour migrants to the Republic of South Africa and the Middle East. Addis Ababa, ET: Forum for Social Studies.

Kiarnersi, S., Jules, R. & Zhang, Y. (2021). Associations between hurricane exposure, food insecurity and microfinance; a cross-sectional study in Haiti. World Development, 145(1): 1-9.

Klarreich, K. and Polman, L. (2012). The NGO republic of Haiti. The Nation, Archive, pp. 1. Retrieved from https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/ngo-republic-haiti.

Laing A, Ramos Miranda A. 2018. Chile sends 176 Haitian migrants home on criticized ‘humanitarian flight.’ Reuters, Emerging Markers, pp. 1. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-chile-migrants/chile-sends-176-haitian-migrants-home-on-criticized-humanitarian-flight-idUSKCN1NC30V

Makina, D. (2013). Migration and characteristics of remittance senders in South Africa. International Migration, 51(1): 148-158. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2435.2012.00746.x.

Marcelin, L.H. & Cela, T. (2017a). After Hurricane Matthew: Resources, capacities, and pathways to recovery and reconstruction of devastated communities in Haiti. Port-au-Prince, HT: Interuniversity Institute for Research and Development (INURED).

Marcelin, L. H., Cela. T. (2017b). Republic of Haiti: Country of Origin Information Paper. Retrieved from: http://www.inured.org/uploads/2/5/2/6/25266591/unchr_coi_haiti_final_redacted_report_inured.pdf

Marcelin, L. H., Cela, T. & Shultz, J. M. (2016). Haiti and the Politics of Governance and Community Responses to Hurricane Matthew. Disaster Health, 3(4): 1-11. doi: 10.1080/21665044.2016.1263539.

Martin, S., Ferris, E. (2017). Border Security, Migration Governance and Sovereignty. Geneva, CH: International Organization for Migration (IOM).

Mohapatra, S., Joseph, G. & Ratha, D. (2009). Remittances and natural disasters: Ex-post response and contribution of ex-ante preparedness. Policy Research Working Paper 4972. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Morley, S. P., Bookey, B. & Bloch, I. (2021). A journey of Hope: Haitian women’s migration to Tapachula, Mexico. San Francisco, California: University of California, Hastings.

Muira, H. (2020). The Haitian migration flow to Brazil: Aftermath of the 2010 earthquake. Retrieved from: http://labos.ulg.ac.be/hugo/wp-content/uploads/sites/38/2017/11/The-State-of-Environmental-Migration-2014-149-165.pdf

Nieto, C. (2014). Migración haitiana a Brasil: Redes migratorias y espacio social transnacional. Buenos Aires, AG: CLACSO.

Observatório das migrações internacionais (OBMigra). (2019). Relatório Anual do Observatório das Migrações Internacionais 2019. Retrieved from: https://portaldeimigracao.mj.gov.br/images/relatorio-anual/RELAT%C3%93RIO%20ANUAL%20OBMigra%202019.pdf.

Observatório das migrações internacionais (OBMigra). 2020. Relatório Anual do Observatório das Migrações Internacionais 2020. Retrieved from: https://portaldeimigracao.mj.gov.br/images/dados/relatorio-anual/2020/OBMigra_RELAT%C3%93RIO_ANUAL_2020.pdf.

Organisation internationale pour les migrations (OIM). 2015. Migration en Haïti Profile migratoire national 2015. Geneva, CH: IOM.

Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) & Interuniversity Institute for Research and Development (INURED). (2017). Interactions entre politique publiques, migration et développement en Haïti. Paris, FR: OECD.

Orozco, M. (2017). Migrants and the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Remittances. Inter-American Dialogue, Uploads, pp. 1. Retrieved from: https://www.thedialogue.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Migration-remittances-and-the-impact-of-the-pandemic-3.pdf.

Orozco, M. (2006). Understanding the remittance economy in Haiti. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). (2021). Haiti earthquake August 2021. Wasington D.C.: PAHO. Retrieved from: Haiti Earthquake August 2021 - PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization.

Paz, I. G. 2021. Strong earthquake rocks Haiti, kills hundreds. New York Times, World, pp. 1. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/live/2021/08/14/world/haiti-earthquake.

Perakis, M. (2011). The Short and Long Run Effects of Migration and Remittances: Some Evidence from Northern Mali. Agricultural & Applied Economics Association’s 2011 AAEA & NAREA Joint Annual Meeting. Retrieved from: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/103704.

Ratha, D. & Shaw, W. (2007). South-south migration and remittances, World Bank Working Paper No. 102. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Ratha, D., Xu, Z. (2008). Migration and Remittances Factbook 2008. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Schlabach C. (2020). Torn between humanitarian ideals and U.S. pressure, Panama screens migrants from around the world. Cronkite News, News, pp. 1. Retrieved from: https://cronkitenews.azpbs.org/2020/07/02/humanitarian-flow-panama-migrants/

Schüler, S. (2020). Haïti: après l’opération pays lock, voyage à travers des provinces en Crise [Podcast]. Retrieved from: https://www.rfi.fr/fr/podcasts/20200205-haiti-operation-pays-lock-voyage-provinces-crise.

Short, P., Hossain, M., & Adil Khan, M. (2020). South-south migration: Emerging patterns, opportunities and risks. New York: Routledge.

Shultz, J.M., Cela, T., Marcelin, L.H. et al. (2016). The Trauma signature of the 2016 Hurricane Matthew and the psychosocial impact on Haiti. Disaster Health, 3(4): 1-18. doi: 10.1080/21665044.2016.1263538.

Lopez-Ekra, S., Aghazarm, C., Kötter, H. & Mollard, B. (2011). The impact of remittances on gender roles and opportunities for children in recipient families: research from the International Organization for Migration, Gender & Development, 19(1): 69-80. doi: 10.1080/13552074.2011.554025.

Ugarte Pfingsthorn, S. (2020). ‘I Need to Work to Be Legal, I Need to Be Legal to Work.’ Migrant Encounters, Haitian Women, and the Chilean State [Doctoral thesis]. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.53123.

U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). 2021. Foreign-born Worker: Labor Force Characteristics — 2020 [Press release]. Retrieved from: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/forbrn.pdf.

Van Hear, N. & N. Sørensen, N. (2015). The migration-development nexus (1st ed.). Geneva, CH: International Organization for Migration.

Wejsa, S. & Lesser, J. (2018). Migration in Brazil: the Making of a multicultural society. Migraton Policy Institute, News, pp. 1. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/migration-brazil-making-multicultural-society.

Wendelbo, M., China, F., Dekeyser, H., Taccetti, L., Mori, S., Aggarwal, V., Alam, O., Savoldi, A. & Zielonka, R. (2016). The Crisis Response to the Nepal Earthquake: Lessons Learned. Brussels, BE: European Institute for Asian Studies.

World Bank. (2020). Migration and Development Brief 33 / Phase II: COVID-19 Crisis Through a Migration Lens. Retrieved from https://www.knomad.org/publication/migration-and-development-brief-34.

World Bank. (2021a). Personal Remittances, Received (% of GDP) – Haiti [Dataset]. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS?locations=HT.

World Bank. (2021b). Migration and Development Brief 34 / Resilience: COVID-19 Crisis Through a Migration Lens. Retrieved from: https://www.knomad.org/publication/migration-and-development-brief-34.

World Bank. (2021c). Migration and Development Brief 35 / Recovery: COVID-19 Crisis Through a Migration Lens. Retrieved from https://www.knomad.org/publication/migration-and-development-brief-35

World Bank. (2022). Migration and Development Brief 36 / A Wari in a Pandemic / Implications of the Ukraine crisis and COVID-19 on global governance of migration and remittance flows. Retrieved from https://www.knomad.org/publication/migration-and-development-brief-36.

Yang, D. (2011). Migrant Remittances. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(3): 129-152. doi: 10.1257/jep.25.3.129.

Yang, D., & Choi, H. (2007). Are Remittances Insurance? Evidence from Rainfall Shocks in the Philippines. The World Bank Economic Review, 21(2), 219-248.

Yates, C. (2021). Haitian migration through the Americas: A decade in the making. Washington, D.C.: Migration Policy Institute.

Ziff, T. & Preel-Dumas, C. (2018). Coordinating a human response to the influx of Haitians in Chile. Inter-American Dialogue, Uploads, pp. 1. Retrieved from: https://www.thedialogue.org/blogs/2018/09/the-influx-of-haitian-migrants-in-chile/

1 Interuniversity Institute for Research and Development (INURED). Coordinator. Ph.D. in International Educational Development. Email: toni.cela@inured.org

2 Interuniversity Institute for Research and Development (INURED. Data Analyst.

Email: M.Fidalgo1@umiami.edu

3 Interuniversity Institute for Research and Development (INURED) and University of Miami. PhD. in Social Anthropology. Professor. Email: LMarcel2@miami.edu

4 Global Migration Group. ‘Remittances’, in Global Migration Group (eds.) Handbook for Improving the Production and Use of Migration Data for Development. Global Knowledge Partnership for Migration and Development (KNOMAD), World Bank: Washington, D.C., 2017, pp. 65-78.

5 Jacqueline Irving, Sanket Mohapatra and Dilip Ratha. ‘Migrant Remittance Flows. Findings from a Global Survey of Central Banks’, World Bank Working Paper No. 194, World Bank, Washington, D.C., 2010. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/850091468163748685/pdf/538840PUB0Migr101Official0Use0Only1.pdf

6 Although the aim of the article is not to compare total remittance estimates from BOP statistics and household-level surveys, Acosta et al. (2006) found that the former produce estimates that are up to ‘ten percentage points of gross domestic product higher than Household Survey data’ in contexts such as Haiti and El Salvador. Although the estimates appear to be consistent, both sources likely underestimate remittance flows. For more information see: Pablo A. Acosta, Cesar A. Calderón, Pablo Fajnzylber, and Humberto López. Remittances and Development in Latin America. The World Economy, 29 (7): 957-987, 2006. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9701.2006.00831.x.

7 Institut Haïtien de Statistique et Informatique (IHSI). Haïti-Enquête sur les conditions de view des ménages après Séisme 2012. Port-au-Prince: Ministere de l’Economie et des Finances, 2012.

8 Peyi Lòk, or ‘country lockdown,’ officially began in September 2019 when political opposition groups joined forces to demand the Haitian government account for over USD 2 billion in missing funds from the Petrocaribe deal with Venezuela. Petrocaribe provided Haiti with oil at competitive rate with favorable repayment terms to facilitate investments in infrastructure, health, education, and agriculture.

9 Orozco (2006) shows that the longer the Haitian migrants had lived in the United States, the higher the amount remitted.

10 The authors infer that this is due to the oversampling of urban centres around the Port-au-Prince Metropolitan Area (PPMA) where educational attainment is higher than in rural areas.

11 Manuel Orozco. Understanding the remittance economy in Haiti. World Bank: Washington, D.C., 2006.

12 Caitlyn Yates. Haitian migration through the Americas: A decade in the making. Washington, D.C.: Migration Policy Institute, 2021.

13 Carrie Kahn. 2021. On Mexico’s southern border, the latest migration surge is Haitian. Accessed on December 20, 2021, at: https://www.npr.org/2021/12/18/1065135970/on-mexicos-southern-border-the-latest-migration-surge-is-haitian.

14 Carrie Kahn. 2021. On Mexico’s southern border, the latest migration surge is Haitian. Access ed on December 20, 2021, at: https://www.npr.org/2021/12/18/1065135970/on-mexicos-southern-border-the-latest-migration-surge-is-haitian.

Fecha de recepción: 29 de julio del 2022 • Fecha de aceptación: 7 de octubre del 2022 • Fecha de publicación: 30 de noviembre del 2022

Revista de Relaciones Internacionales por Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional.

Equipo Editorial

Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica. Campus Omar Dengo

Apartado postal 86-3000. Heredia, Costa Rica