REVISTA 97.2

Revista Relaciones Internacionales

Julio-diciembre de 2024

ISSN: 1018-0583 / e-ISSN: 2215-4582

doi: https://doi.org/10.15359/97-2.3

|

Strategic Enhancement and Differential Governance: China’s Partnership Diplomacy in Latin America Mejora Estratégica y Gobernanza Diferencial: Diplomacia de Asociación de China en América Latina Xinyu Zhang1(*) ORCID: 0000-0002-9774-7092 |

Abstract:

This paper studies China’s partnership diplomacy and its practice in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). China has constructed an all-round, multi-level, and three-dimensional partnership network in LAC through three stages: strategic exploration, development, and improvement. China has implemented differential governance towards its partners, which enables active shaping and dynamic management of the partnership network. This paper categorizes the 15 partner countries into three types: pivot countries, link countries, and node countries based on their political friendliness with China, geopolitical influence, and potential for economic and trade cooperation. China’s partnerships in LAC are vital support for implementing its diplomatic strategy in the region. However, challenges to this strategy’s development include insufficient mutual support from other diplomatic means, doubts and misinterpretations of the China-Latin America partnership by some Latin American countries, and the political and identity shifts within these countries. To enhance the role of partnerships in maintaining state relations and promoting the implementation of diplomatic strategies, China has introduced new content to its partnership diplomacy in LAC.

Keywords: Chinese diplomacy, China-Latin America relations, cooperation, governance, Latin America and the Caribbean, partnership, strategic alliance

Resumen:

Este artículo estudia la diplomacia de asociación de China y su práctica en América Latina y el caribe (LAC, siglas en inglés). Después de tres etapas de exploración estratégica, desarrollo y mejora, China ha construido una red integral, multi-nivel y tridimensional de asociaciones en LAC. De acuerdo con el grado de amistad política, la influencia geopolítica y el potencial de cooperación económica y comercial de los 15 países asociados con china, este artículo los divide en tres categorías: países de pivote, países de vínculo y países nodales. Las asociaciones de China en LAC son apoyos importantes para que China implemente estrategias diplomáticas en la región. Sin embargo, su desarrollo también enfrenta desafíos, incluido el apoyo insuficiente con otros medios diplomáticos; dudas e interpretaciones erróneas de las relaciones asociativas; y la transformación de identidad nacional de algunos países asociados. Con el fin de fortalecer el papel de las asociaciones en el mantenimiento de las relaciones nacionales y promover la implementación de las estrategias diplomáticas, China ha agregado nuevos contenidos a la diplomacia de asociación en LAC.

Palabras clave: América Latina y el Caribe, asociación estratégica, cooperación, diplomacia china, gobernanza, relaciones sino-latinoamericanas

China has embarked on partnership diplomacy in 1993 when it established a strategic partnership with Brazil. Since the launch of China’s Belt and Road Initiative in 2013, China’s partnership diplomacy has become more active and vigorous. By 2022, China had established diplomatic relations with 181 countries and diplomatic partnerships with 113 countries and regional organizations worldwide. In the early 21st century, the economic and trade relations between China and Latin American countries have become increasingly close. Following rapid development, Sino-Latin American relations are now undergoing upgrades and transformations. As of 2023, China has established partnerships with 15 Latin American countries and one regional organization at various levels, and bilateral partnerships have been upgraded 12 times. The construction of China’s partnership network in LAC, which has become an essential support for implementing the country’s foreign policy, is consistent with China’s strategic layout of diplomacy in the region.

The literature on China’s partnership diplomacy can broadly be categorized into three groups. The first category is epistemological research on the definition and function of China’s partnerships. Scholars have varying understandings and interpretations of China’s partnership concept based on different perspectives. Some scholars view partnerships as tools for managing foreign policy (Weber, 2007; Portela, 2011), while others view them as models for establishing independent and autonomous cooperative relationships to achieve common goals (Ko, 2006; Men, 2005; Dong, 2019). Scholars also often compare the concept of “partnership” with “alliance” and “coalition” (Liu, 2015; Gu, 2016; Zhou, 2016).

The second area of research is the ontological scope of China’s partnership diplomacy, which encompasses its background, evolution, characteristics, and impact. Wang (2005) indicates that China’s decision to pursue partnership diplomacy is based on the need to respond to complex international situations and to meet the requirements of comprehensive national power and national interests. Feng and Huang (2014) argue that the strategic partnership boom is a product of China’s embrace of globalization and multidimensional diplomacy. Strüver’s (2017) empirical study of China’s partnership relations finds that alignment behaviors are based on common interests rather than shared values. Other researchers have studied the factors affecting the upgrading of China’s partnerships from the perspectives of cooperation deepening theory, alternative alliance theory, and partnership types (Masher, 2016; Yu, 2015; Sun, 2017). Scholars also pay attention to the impact of partnerships on changes in national power and the international system, including challenges related to regional security, globalization, and other global affairs (Envan and Hall, 2016; Yu, 2015; Renard, 2016).

The third category consists of specific case studies, which involve practical experience of China’s partnership diplomacy in various countries and regions. Scholars focus more on partnerships between China and major countries such as the United States, Australia, Russia, and Brazil (Yu, 2016; Zhao, 2014; Guan, 2022; Xu, 2017). Multilateral partnerships are also a research focus for scholars, such as the China-EU partnership, the China-ASEAN strategic partnership, the China-Middle Eastern Countries partnership, and the China-Latin America comprehensive partnership (Sun & Ding, 2017; Cottey, 2021; Gerdel and Días, 2021; Qin & Liang, 2022).

The existing literature provides essential references for this paper to study China’s partnership diplomacy in LAC. Nevertheless, further exploration is necessary to address several remaining issues. First, scholars have focused more on China’s partnership diplomacy with major economies and its neighboring countries, while there have been insufficient case studies and empirical research on partnership diplomacy with developing countries, including Latin American countries. Second, the establishment, maintenance, and updating of partnerships are two-way or multi-directional interactive processes; yet, existing literature rarely discusses how these processes develop and are managed. Borquez and Bravo (2020) argue that China has seven strategic associations in South America categorized into three profiles: ideologically affiliated partners, geo-economic partners, and business partners. However, these authors did not explain why hierarchical differences exist in the Sino-Latin America partnership network. Therefore, this paper aims to address how China dynamically develops and diversifies its partnerships in LAC.

The literature review above also shows that there is no consensus in the academic community on the meaning of “partnership”. In the field of international relations, the phenomenon of alliances or alignments between states has a long history. Most scholars in Western countries do not clearly distinguish between the concept of “partnership” and “alliance”, believing that “partnership” is a supplementary form of alliance strategy. However, in the light of the purpose, alliances are intended to balance threats, while partnerships are founded on common interests. Based on this, some scholars contend that the best definition for partnerships is that of ‘interest-driven alignments’ (Strüver, 2017). In addition, in terms of content, the alliances primarily emphasize security commitments and coalitions in the military field, while partnerships do not necessarily involve security and military cooperation. This distinction is particularly important in the case of China, which is characterized by a networked partnership diplomacy where partnering countries can establish cooperation mechanisms in the military field as well as engage in partnerships in economic, cultural, and other fields (Gu, 2016). This article argues that there are several standard views on the factors or principles that must be followed to establish and develop partnerships. Firstly, the two parties involved in a partnership must be equal and independent. If the two parties have a differential relationship in terms of dependence, the partnership loses its basis for existence. There may still be differences between the two parties in the partnership, but it is essential to have a mechanism to resolve them. Secondly, cooperation to achieve mutual goals and interests is the driving force behind forming and developing partnerships. Thirdly, cooperation among partners should be mutually beneficial, long-lasting, and multifaceted. Consequently, this article argues that “partnership” is a form of long-term planning for international actors, primarily sovereign states, to establish cooperative relationships with other countries or international organizations. The partnership is established to achieve both their interests and common interests with others, based on the principles of equality, cooperation, and mutual benefit.

On this basis, China’s partnership strategy is an essential national foreign strategy rather than a temporary solution. This article finds that China has been proactively shaping partnerships with Latin American countries, through strategic enhancement and differential governance, with the aim of maintaining stable Sino-Latin American relations in the long term and, on this basis, creating a favorable environment for implementing China’s international strategy. Strategic enhancement refers to the role of partnership diplomacy in China—Latin America relations. Differential governance refers to China’s management approach towards its Latin American partners. In addition to the introduction, this article consists of four parts. The second part covers the evolution of China’s diplomatic partnership with LAC and analyzes its main layout. The third section explains China’s differential governance of its partnerships with Latin American countries. The fourth section explores the challenges facing China’s partnerships in the region. The fifth and final section provides a conclusion and outlines future directions for research on China’s partnership diplomacy.

2.Strategic Enhancement: The Dynamics and Evolution of China’s Partnership Diplomacy in Latin America

In the early 1990s, the international situation underwent significant changes due to the drastic changes in Eastern Europe and the collapse of the Soviet Union. Concurrently, China also faced challenges in maintaining domestic political stability and economic growth. Western countries, particularly the United States, imposed sanctions on China, citing human rights concerns. As a result, China’s foreign policy encountered significant challenges. In 1992, during the 14th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC), China established a diplomatic strategy rooted in the ideas of an “independent and peaceful policy,” “non-alignment,” and “non-hegemony.” The order of precedence for this diplomatic strategy was to rely on the Third World, develop friendly and cooperative relations with all countries, and support the positive role of the United Nations Security Council (Men, 2009). In this context, China established a strategic partnership with Brazil in 1993, initiating the practice of partnership diplomacy. Based on typical examples of China’s establishment and development of partnerships with Latin American countries, China’s partnership diplomacy in this region can be divided into three phases: strategic exploration, strategic development, and strategic improvement.

2.1Phase of Strategic Exploration (1993-2002)

Brazil became the first country in the world to establish a strategic partnership with China, primarily due to their shared basis, will, and potential for such a relationship. First, similar development strategies and common interests formed the basis of a strategic partnership between China and Brazil. China is the largest developing country in the world and the largest country in Asia. Brazil is the largest developing country in the Western Hemisphere and the largest country in LAC. The two countries have no historical grudges or conflicts of political interests while sharing many common interests due to their similar levels of development at that time. Second, China and Brazil were willing to seek a more comprehensive and solid relationship. In the early 1990s, China maintained rapid economic growth but faced a complex international situation, while Brazil consistently maintained a non-interventionist stance regarding China’s internal affairs. As a result, China regarded Brazil as a “loyal friend” (Biato, 2010). Strengthening cooperation with Brazil would not only enhance China’s international influence but also provide access to high-quality raw materials, new markets, and sources of capital for sustained economic growth. Simultaneously, Brazil was facing an external debt crisis, economic recession, and increasing social conflicts. Consequently, it hoped to capitalize on the opportunities presented by China’s economic development to promote exports and investment in China. Third, the two countries had significant potential for economic and trade cooperation, as well as room for growth in international affairs due to their similar positions on global issues, such as promoting South-South cooperation and establishing a new international political and economic order.

At this stage, given the pressure of sanctions from developed Western countries and changes in the neighboring environment, China regarded improving its relations with major powers and neighbors as a top priority. Following Brazil, China began implementing its partnership strategy in neighboring regions and with great powers, including Russia (1994), Pakistan (1996), Nepal (1996), ASEAN (1996), France (1997), the United States (1997), the European Union (1998), and the United Kingdom (1998). It was not until 2001 that China established a “strategic partnership for common development” with Venezuela, which became China’s second strategic partnership in LAC. Since establishing diplomatic relations in 1974, China and Venezuela have steadily developed exchanges and cooperation in politics, economics, trade, culture, science, and technology. In the mid-1990s, China’s growing dependence on petroleum imports led to an increased willingness to expand cooperation with Venezuela to improve energy security. Meanwhile, as Hugo Chávez took office as president in 1999, Venezuela focused on recovering and maintaining oil sovereignty, reducing dependence on the United States. Chávez viewed China as an important partner and a balancing force (Xie, 2019). Overall, during the initial stage, China’s diplomatic strategy did not prioritize LAC, resulting in a limited number of established partnerships in the region.

2.2Phase of Strategic Development (2003-2013)

China’s comprehensive national power increased dramatically in the 21st century, marked by rapid economic growth. Therefore, China needed to improve and strengthen diplomatic relations with other countries. Compared to the previous phase, China’s diplomatic strategy shifted its focus toward middle-developed and developing countries (Men, 2009). China took the initiative to position itself strategically in LAC. Simultaneously, due to changes in the international landscape and driven by growing economic and trade ties between China and LAC, China has become a crucial strategic option for Latin American countries seeking to diversify their foreign relations. As a result, the number of China’s partnerships in LAC grew significantly. First, countries with strong economic capabilities in the region were the first choice for China to establish partnerships. For instance, in December 2003, China’s former Premier Wen Jiabao visited Mexico, and the two countries formally announced the establishment of a strategic partnership. In June and November 2004, then-President Hu Jintao and Argentine former President Nestor Carlos Kirchner exchanged visits, and the two sides decided to establish a strategic partnership. Similarly, during Hu’s visit to Chile in November 2004, China and Chile announced the establishment of a comprehensive cooperative partnership. In 2008, during Hu’s visit to Peru, the two countries established a strategic partnership.

Second, China chose to establish partnerships with countries that could have a radiating effect on their neighbors to deepen its strategic ties with sub-regions where it does not have a dominant position. In February 2005, China and Jamaica established a friendly partnership for common development. Jamaica is one of China’s largest trading partners in the English-speaking Caribbean. After establishing the partnership, the Jamaican government formally recognized China as a market economy. This recognition served as a positive model in the Caribbean region. In the same year, China established a friendly and cooperative partnership for mutually beneficial development with Trinidad and Tobago, a founding member of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) and the Association of Caribbean States (ACS). It is also a critical oil exporter in the region. In 2006, China and the Caribbean diplomatic community issued a joint press communiqué in Beijing, establishing a consultation mechanism and agreeing to expand cooperation further.

During this second phase, China established six new pairs of partnerships in Latin America and upgraded five pairs of partnerships. In 2012, China overtook the United States as Brazil’s top trading partner, with a total trade volume of $75.4 billion with Brazil. On June 21 of the same year, after Premier Wen Jiabao concluded talks with then-Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff in Rio de Janeiro, the two governments issued a joint statement, deciding to elevate China-Brazil relations to a comprehensive strategic partnership and signing a Ten-Year Cooperation Plan. In the same year, Wen visited Chile and held talks with former Chilean President Sebastian Piñera, during which the two sides announced establishing a strategic partnership between the two countries. In April 2013, former Peruvian President Ollanta Humala paid his first visit to China, during which the two countries agreed to elevate bilateral relations to a comprehensive strategic partnership. In June of the same year, during his visit to Mexico, Chinese President Xi Jinping met with then-Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto and announced that China-Mexican relations would be upgraded to a comprehensive strategic partnership. After his visit to Mexico, President Xi also visited Trinidad and Tobago, upgrading bilateral relations to a comprehensive cooperative partnership characterized by “mutual respect, equality, mutual benefit, and common development.”

In this phase, China’s understanding of partnership diplomacy has been deepening, and the differential strategy of its partnership network has seen improvement. This advancement is consistent with China’s strategic layout of its diplomacy in the region. The basic framework for the future layout of China’s partnership strategy in LAC has also been established at this stage. Based on this, the country-specific geopolitical pattern of the Sino-Latin America relations became increasingly balanced, which not only enhances China’s ability to manage the general diplomacy in the region but also strengthens China’s diplomatic flexibility in geopolitics towards the region. (Zheng, 2009).

2.3Phase of Strategic Improvement (2014-Present)

In the second decade of implementing its partnership strategy, China transformed partnerships into a diplomatic tool with unique Chinese characteristics. In November 2012, the Communist Party of China proposed the establishment of a new type of more equal and balanced global partnership for development, thus elevating partnership diplomacy to a new strategic level. As China’s partnerships with developed countries proliferated, China’s partnership strategy began to focus primarily on developing countries. In this context, LAC experienced another wave of partnership-building with China. Given the political and social diversities in the Latin American region, the differences among regional powers in their development models and governance philosophies, and the difficulties of the regional integration processes, utilizing the platform of regional organizations to build a multilateral cooperation network for China’s partnerships is of great significance for constructing a more comprehensive and balanced Sino-Latin American relationship. Consequently, the first direction of China’s partnership strategy in LAC was to utilize existing regional organizations as platforms to build regional partnerships. The Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), established in December 2011, created conditions for constructing China’s multilateral partnerships with the region. In July 2014, President Xi Jinping held his first collective meeting with Latin American leaders and representatives in Brazil. He proposed developing a China-CELAC Comprehensive Partnership through a cooperation framework of the China-CELAC Forum. At the Foreign Affairs Work Conference of the Central Committee of the CPC in November 2014, President Xi Jinping proposed the establishment of a global partnership network, emphasizing adherence to the principle of non-alignment.

The China-CELAC Comprehensive Partnership, the China-ASEAN Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, the China-EU Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, and the China-Africa Comprehensive Strategic Partnership are all parts of China’s global partnership network. Establishing China’s collective partnership in Latin America marks the completion of China’s overall diplomatic layout for cooperation in all developing regions.

Maintaining the rapid growth of new partnerships is the second way for China to upgrade its partnership strategy in LAC at this stage. In January 2015, when former Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa made a state visit to China and attended the first ministerial meeting of the China-CELAC Forum, China and Ecuador announced the establishment of a “strategic partnership.” In the same period, China and Costa Rica announced the establishment of a strategic partnership characterized by equality, mutual trust, and win-win cooperation. Costa Rica became the first Central American country to have a strategic partnership with China. In October 2016, former Uruguayan President Tabare Vazquez visited China, and the two countries announced the establishment of a strategic partnership. In June 2018, during former Bolivian President Evo Morales’ visit to China, China and Bolivia jointly announced the establishment of a strategic partnership. In November 2019, during the state visit to China of Suriname’s then-President Desi Bouterse, the relationship between China and Suriname was upgraded to a “strategic cooperative partnership.”

While the number of partnerships increases, upgrading previous partnerships has become the third way for China to expand its partnership strategy in Latin America. In July 2014, President Xi Jinping and President Nicolás Maduro announced the upgrading of China-Venezuela relations to a “comprehensive strategic partnership.” The two sides signed 16 cooperation documents covering energy, mining, finance, infrastructure construction, agriculture, higher technology, and other assorted fields. During the same period, President Xi paid a state visit to Argentina, where China and Argentina announced the upgrading of bilateral relations to a “comprehensive strategic partnership.” In November 2016, during Xi’s state visit to Ecuador, China and Ecuador announced the upgrading of bilateral relations to a “comprehensive strategic partnership.” During the same period, Xi conducted a state visit to Chile, where China and Chile announced the upgrading of bilateral relations to a “comprehensive strategic partnership.” In November 2019, Prime Minister Andrew Holness of Jamaica paid an official visit to China and attended the second China International Import Expo. During the visit, the leaders of these two countries jointly elevated the bilateral relationship to a “strategic partnership.” In September 2023, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro paid his third state visit to China, and the two countries decided to upgrade bilateral relations to an “all-weather strategic partnership”, which is the highest level of cooperation in China’s current partnership network in Latin America. The term “All-weather” suggests that the cooperation between the two countries would continue regardless of how the external environment changes (Li and Ye, 2019). Overall, at this stage, China’s partnership strategy in LAC emphasizes both integrity and hierarchy. In addition, it can be observed that the partnership has achieved positive results in strengthening cooperation between these countries.

Table 1: The Establishment and Upgrading of Partnerships between China and Latin American Countries

|

Year |

Countries or Organizations Establishing Partnerships |

Count |

Countries or Organizations Upgrading Partnerships |

Count |

|

1993 |

Brazil |

1 |

0 |

|

|

2001 |

Venezuela |

1 |

0 |

|

|

2003 |

Mexico |

1 |

0 |

|

|

2004 |

Argentina, Chile |

2 |

0 |

|

|

2005 |

Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago |

2 |

0 |

|

|

2008 |

Peru |

1 |

0 |

|

|

2012 |

0 |

Brazil, Chile |

2 |

|

|

2013 |

0 |

Mexico, Peru, Trinidad and Tobago |

3 |

|

|

2014 |

Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) |

1 |

Argentina, Venezuela |

2 |

|

2015 |

Ecuador, Costa Rica |

2 |

0 |

|

|

2016 |

Uruguay |

1 |

Ecuador, Chile |

2 |

|

2018 |

Bolivia |

1 |

0 |

|

|

2019 |

Suriname |

1 |

Jamaica |

1 |

|

2023 |

Colombia |

0 |

Venezuela, Uruguay |

2 |

|

Total |

16 |

12 |

Source: Own elaboration.

3.Differential Governance: How China Conducts Partnership Diplomacy in Latin America

Partnership diplomacy is a rational choice for China’s diplomatic development, serving as an essential means of realizing national interests (Wang, 2018). Partnerships between China and Latin American countries are dynamic, evolving in response to changes in the international situation, bilateral or multilateral relations, and adjustments in their respective foreign policies. Since 1993, China has adopted a differential governance approach towards its partner countries in the region. This approach facilitates the hierarchical deployment of China’s diplomatic strategy towards LAC and enables dynamic development in China’s partnership management in the region. Consequently, China prioritizes the sincerity of its partners’ collaboration and the achievement of mutual cooperation. The differential governance of partnerships also promotes the precise alignment of China’s strategic diplomatic goals with Latin American countries, which allows China to identify preferred target countries for strategic collaboration in LAC quickly, and then rationally deploy and accurately invest diplomatic resources in them. Therefore, China considers several factors when establishing and upgrading partnerships, including the target country’s political stance towards China, its geopolitical influence, and the potential for economic cooperation between the two sides. Based on factors such as willingness (political friendliness), foundation (geopolitical influence), and potential (economic cooperation), this paper categorizes China’s 15 partner countries in LAC into three levels: pivotal countries, link countries, and node countries.

Table 2. Types of Partnership between China and Latin American Countries (as of December 2023)

|

No. |

Country |

Level of Partnership |

Type of Partnership |

Influencing Factors |

|

1 |

Venezuela |

Pivotal Countries |

All-weather Strategic Cooperative Partnership |

1. Firm support of China’s core interests, and ability to cooperate with China in global multilateral frameworks; 2. Frequent high-level exchanges; 3. The closest economic and trade ties |

|

2 |

Brazil |

Comprehensive Strategic Partnership |

||

|

3 |

Argentina |

|||

|

4 |

Chile |

|||

|

5 |

Mexico |

|||

|

6 |

Ecuador |

|||

|

7 |

Peru |

|||

|

8 |

Uruguay |

|||

|

9 |

Bolivia |

Link countries |

Strategic Partnership |

1. Helping to expand China’s international cooperation; 2. Ability to play a radiating role in the neighboring areas; 3. The relatively close economic and trade ties |

|

10 |

Jamaica |

|||

|

11 |

Costa Rica |

|||

|

13 |

Colombia |

|||

|

14 |

Suriname |

Node countries |

Strategic Cooperative Partnership |

1. High degree of friendship with China; 2. Exemplary role in the regional and global scope; 3. The weak economic and trade ties |

|

15 |

Trinidad and Tobago |

Comprehensive Cooperative Partnership |

Source: Own elaboration.

Pivotal countries are vital in supporting China’s partnership network in LAC. China’s one all-weather strategic partner (Venezuela) and seven comprehensive strategic partners (Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Mexico, Ecuador, Peru, and Uruguay) constitute the pivotal countries of China’s partnership diplomacy. These countries have the following three characteristics. Firstly, they are regional strategic partners with global influence and can provide firm support to China on international occasions. For example, China has been Brazil’s largest trading partner for 14 consecutive years, and Brazil is China’s ninth-largest trading partner. Both countries are large developing countries with emerging markets, have similar philosophies regarding global governance, and have established long-term cooperation in various multilateral mechanisms, including the United Nations, the G20, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and BRICS. As another example, in 2016, China and Ecuador elevated their relationship to a “comprehensive strategic partnership.” As Ecuador held the rotating presidency of the Group of 77 the following year, enhanced relations with Ecuador promoted closer collaboration between the Group of 77 and China in multilateral institutions.

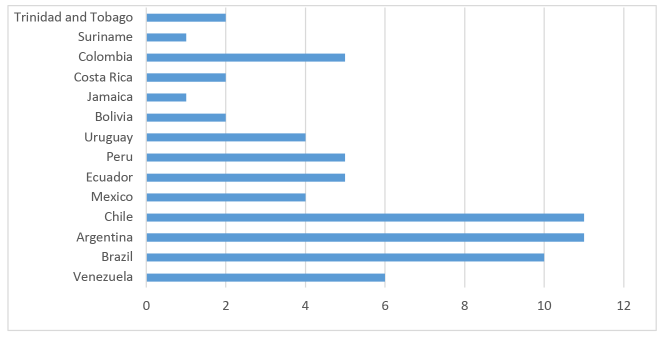

Secondly, there are frequent high-level visits between China and the pivotal countries. Exchanges between heads of state play a top-level design and strategic leading role in Sino-Latin American relations. Figure 1 shows that the frequency of exchanges between the heads of state of China and its pivotal partners is higher than that of other types of countries. Through frequent high-level exchanges, the two sides engage in frank and in-depth communication on issues of mutual concern, which can promptly eliminate misunderstandings, promote the management and control of differences, and help enhance political and strategic mutual trust.

Thirdly, the pivotal countries are China’s most important economic and trade partners in the region. China is the largest trading partner of Brazil, Chile, Peru, and Uruguay, and the second-largest trading partner of Argentina, Ecuador, and Mexico.

Figure 1. Frequency of Exchanges between the Heads of State of China and its Latin American Partners (2014-2023) (Including Multilateral Meetings, State Visits, Telephone or Video Conferences).

Source: Own elaboration based on https://www.fmprc.gov.cn.

Link countries are crucial in building bridges and bonds within the partnership network between China and LAC. Four strategic partners (Bolivia, Jamaica, Costa Rica, and Colombia) constitute the link countries for China’s partnership diplomacy in the region. These countries help expand China’s international cooperation, possess the ability to play a radiating role in neighboring areas, and have relatively close economic and trade ties with China. For instance, Jamaica is among China’s largest trading partners in the English-speaking Caribbean. In February 2005, China and Jamaica established a friendly partnership for common development. It was not until 2019 that the bilateral relationship was upgraded to a strategic partnership. In April 2019, China and Jamaica signed the Memorandum of Understanding on Belt and Road Cooperation. Jamaica is the first English-speaking Caribbean country to sign a cooperation plan with China to promote the construction of the Belt and Road Initiative, which could serve as a positive model for the Caribbean region.

China established strategic cooperative partnerships or comprehensive cooperative partnerships with node countries that have a high degree of friendship with China and can play an exemplary role regionally and globally but have weak economic and trade ties with China. Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago are two node countries in the region. Suriname was among the first Caribbean countries to recognize the one-China principle and establish diplomatic relations with China. For over 40 years, China-Suriname relations have been a priority in China’s relations with Caribbean countries. In May 2018, Suriname became the first Caribbean country to sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on the Belt and Road Initiative with China. In the Joint Press Communiqué of the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of Suriname signed in 2019, Chinese President Xi Jinping stated that China-Surinamese relations can be considered a model of friendly relations and equal treatment between countries of different sizes (Xinhua, 2019).

4.Challenges for China’s Partnership Diplomacy in Latin America

China’s diplomatic partnerships in LAC have not only effectively promoted the development of bilateral and regional relations between China and LAC but have also elevated China’s discourse regarding institutional and public opinion in the international stage. This reflects the new trend of cooperation among countries of the Global South. Nonetheless, constructing China’s partnership network in LAC is a challenging and long-term project, with many risks and challenges to maintaining and expanding this strategy.

First, partnership diplomacy is essential to China’s diplomatic strategy but should cooperate better with other diplomatic means. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi stated that China advocated for a new type of international relations and sought to build a “Community of Common Destiny.” The latter encompasses politics, economics, security, civilization, ecology, and various other aspects. The new type of international relations and the community of destiny of humankind play different roles in great power diplomacy with Chinese characteristics. Therefore, partnership diplomacy should also have its development focus and emphasize better service and cooperation with other diplomatic paths. However, within China’s overall diplomatic framework, there has been no mechanism for integrating and coordinating partnership diplomacy with other diplomatic tools. As a result, few partnerships become formalistic, and the strategy’s effectiveness needs clear measurement standards. Consequently, it is necessary to clarify its strategic goals within the overall diplomatic framework and strengthen mechanisms for regularizing and synergizing its exchanges with other forms of diplomacy to improve the effectiveness of partnership diplomacy.

Second, in the context of increasing competition between China and the United States, some Latin American countries have concerns and misunderstandings about the Sino-Latin America partnership. As part of the great power competition, the U.S. policy towards LAC has shown signs of hegemonic intentions in recent years. The U.S. requires LAC countries to have an “exclusive relationship” with the U.S., and thus not with China (Dussel, 2019). Donald Trump adjusted its policy towards LAC since taking office to reverse the trend of relative estrangement from the region during the Bush and Obama administrations. The Biden administration attempted to further consolidate the United States’ dominant position in LAC, thereby increasing strategic attention and resource investment in the region. The U.S. has established similar economic partnerships and formed ideological alliances with LAC, such as the Build Back Better World Initiative, the Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity (Americas Partnership), and the Alliance for Democratic Development. China’s main partner countries in LAC, such as Mexico, Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Peru, and Uruguay, have joined the cooperation mechanisms as mentioned above. Telias (2021) argues that in the increasingly competitive environment between these two major powers, LAC must avoid falling into the trap of this dispute. For the Latin American region, in the power game between China and the U.S., it should maintain its independence, avoid mindlessly choosing a camp, and evaluate the situation to profit from it and accelerate its development (Oviedo, 2016).

With the exception of the U.S. and China, some Latin American countries chose to strengthen their partnerships with other nations to balance their global strategic interests. For instance, in July 2021, Mexico signed a strategic partnership agreement with Panama. In October 2022, South Korean Prime Minister Han Deok-soo visited Chile and met with Chilean President Gavriel Borich to upgrade the relationship between the two countries from a comprehensive partnership to a strategic partnership. With this being kept in mind, China’s partnership diplomacy in LAC may face the challenge of intertwining with other partnership networks, which could result in strategic competition or cause an imbalance.

Third, political changes in Latin American countries have led to shifts in priority interests, affecting the stability and sustainability of partnerships with China. In the 21st century, left-wing political parties have come to power in more than ten LAC countries, and a “pink wave” has emerged. In terms of time, the rapid development of China-Latin America relations has coincided with the “pink wave” in LAC (Cui, 2019). Nevertheless, after 2015, the political pendulum in LAC swung rapidly to the right. The political changes in Latin American countries would lead to the divergence of national diplomatic positions, weakening the degree of solidarity and cooperation for regional integration. For instance, the CELAC serves as the platform for the collective partnership between China and LAC, but its development is constrained by regional powers. For example, since taking office in 2019, Jair Bolsonaro, the former right-wing President of Brazil, repeatedly criticized China and the Sino-Brazilian relationship. In addition, the Bolsonaro government suspended its participation in activities within the CELAC framework due to severe disagreements among member states on the Venezuelan issue, which hindered consensus.

Fourth, the transformation of the identity of Latin American countries affects the cooperation within the China-Latin America partnership. Although there is a difference in terms of China’s policy towards LAC from 1949 to the present day (i.e., a very revisionist and politically focused goal until the late 1970s as compared to a less revisionist and economically focused one at present), the guiding doctrine of its policy towards the region has never changed (i.e., “South-South Cooperation” on the basis of the “Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence”) (Chen, 2021). However, some Latin American countries have experienced shifts in national identity, which has altered their perception of China and Sino-Latin American relations, significantly reducing the consensus between China and these Latin American countries on specific global governance issues. For example, Mexico, a founding member of the Group of 77, has become an OECD member and no longer adheres to the position of a developing country on a significant number of issues, such as regional integration and global climate change. Instead, it attempts to act as a bridge between the U.S. and LAC, as well as between developed and developing countries. Similarly, as a significant regional power in LAC, Brazil seeks leadership at the regional level and aims to attain great power status within the global system. For instance, one of Brazil’s foreign policy priorities has been to secure a Permanent Seat on the UN Security Council. Brazil hopes China will explicitly support its bid for a permanent seat. While China supports UN reform and a greater role for Brazil within the organization, its attitude towards Brazil’s accession has been ambiguous, leading to voices questioning the relationship between the two countries in Brazil.

China has gradually constructed an all-round, multi-level, and three-dimensional partnership network in the Latin American region through the three stages of strategic exploration, development, and improvement. China’s partnership diplomacy in LAC has adopted a differential governance approach, which enables an active shaping and dynamic management of the partnership network. This paper categorizes the 15 partnership countries into three types: pivot countries, link countries, and node countries based on their political friendliness with China, geopolitical influence, and potential for economic and trade cooperation. China’s partnership diplomacy in LAC is a vital support for implementing the country’s diplomatic strategy in the region., Nonetheless, challenges to the region’s development still exist including insufficient mutual support with other diplomatic means, doubts and misinterpretations of the China-Latin America partnership by a number of Latin American countries, and political and identity shifts within those countries.

Over the last decade, several Latin American scholars have highlighted the concept of “new triangular relationships”, that is, acknowledging the historic and socio-economic relevance of the US in the region, alongside China’s increasing socio-economic presence in LAC since the end of the twentieth century in terms of trade, foreign direct investments, financing, infrastructure, and even national security and military engagement in specific regions and countries (Dussel, 2022). Amid rising tensions between the U.S. and China, there is still significant room for progress in the developmental partnership between China and LAC. Latin American countries can seize the development opportunities for collective cooperation between China and the region by promoting regional integration. An integrated Latin America could nudge great powers operating in the region to cooperate, acknowledge Latin American priorities, and use great power engagement to further advance regional integration (Goodman and Schneider, 2023). Latin American countries can also establish and improve strategic communication mechanisms with China within the framework of partnership to better understand each other’s core interests and major concerns.

Zapata and Martínez-Hernández (2020) indicate that domestic factors, political cycles, periods of global polarity, and economic conditions determine political convergences of LAC that are closer to China as opposed to the U.S. To enhance the role of partnership in maintaining state relations and promoting the implementation of diplomatic strategies, China has introduced new content for its partnership diplomacy in LAC. On the one hand, this has been achieved by strengthening its cooperation with Latin American countries in multilateral partnerships. A “multilateral partnership” refers to a mode of interaction and structure in which a partnership is not established between two parties, but exists among multiple parties, that is, developing relationships with various countries within a multilateral framework or mechanism (Wang, 2018). For example, on October 18, 2018, at the Belt and Road Energy Ministers’ Meeting in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province of China, 17 countries, including Venezuela, issued a joint ministerial declaration establishing the Belt and Road Energy Partnership with China. On the other hand, partnerships emphasizing cooperation in specific fields or topics have emerged within the traditional bilateral partnerships between China and Latin American countries. For instance, the Joint Statement of the People’s Republic of China and the Federative Republic of Brazil on Deepening the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, signed in April 2023, proposed the creation of a digital economic partnership, a sustainable development partnership, and a partnership based upon technology between companies in the two countries. Future research could analyze partnership diplomacy in comparison to other diplomatic tools practiced by China in LAC, including political party diplomacy, public diplomacy, people-to-people diplomacy, and urban diplomacy. Furthermore, a comparative analysis should be conducted on the partnership networks built by China in various regions.

Biato O. J. (2010). A parceria estratégica sino-brasileira: origens, evolução e perspectivas (1993-2006). Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão.

Borquez A., & Bravo C. (2020). Who are China’s strategic economic partners in South America? Asian Education and Development Studies, 10(3): 445-456. doi: 10.1108/AEDS-09-2019-0153

Cottey A. (2021). The European Union and China: Partnership in Changing Times. The European Union’s Strategic Partnerships: Global Diplomacy in a Contested World, 221-244, doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-66061-1_10

Cui S. J. (2019). 中国和拉美关系转型的特征、动因与挑战 [The Characteristics, Drivers and Challenges of the Transitional Relation of China and Latin America]. Journal of Renmin University of China, 33(03): 95-103 (In Chinese). Available online: http://xuebao.ruc.edu.cn/CN/Y2019/V33/I3/95

Chen C. K. (2021). China in Latin America then and now: A systemic constructivist analysis of China’s foreign policy. Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 50(2): 111-136. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/18681026211034880.

Dong Y. B. (2019). On the Conceptual Analysis of the Reasons for and the Attitudes Towards the Academic Circle towards the Establishment of China’s “Partnership Strategy.” Journal of Jiangnan Social University, 21(03): 63-66 (In Chinese). doi: 10.16147/j.cnki.32-1569/c.2019.03.011

Dussel E. P. (2019). China’s Recent Engagement in Latin America and the Caribbean: Current Conditions and Challenges. China Currents. Working paper. Available online: “https://www.cartercenter.org/resources/pdfs/news/peace_publications/china/china-engagement-latin-america-and-caribbean.pdf” https://www.cartercenter.org/resources/pdfs/news/peace_publications/china/china-engagement-latin-america-and-caribbean.pdf

Dussel E. P. (2022). The New Triangular Relationship between the US, China, and Latin America: The Case of Trade in the Autoparts-Automobile Global Value Chain (2000–2019). Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 51(01): 60-82. doi: 10.1080/08853908.2019.1696256

Envall H. D. P., & Hall I. (2016). Asian Strategic Partnership: New Practices and Regional Security Governance. Asian Politics & Policy, 8(01): 87-105. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/aspp.12241

Feng Z. P., & Huang J. (2014). China’s Strategic Partnership Diplomacy: Engaging with a Changing World. European Strategic Partnership Observatory, (08): 18-19. Working paper. Available online: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/181324/China’s%20strategic%20partnership%20diplomacy_%20engaging%20with%20a%20changing%20world%20.pdf

Gerdel A., & Días J. (2021). China y América Latina Una Asociación Estratégica Integral. Ediciones CVEC.

Gu W. (2016). 网状伙伴外交、同盟体系与“一带一路”的机制建设 [Network Partnership Diplomacy, Alliance System and the Building the Mechanism for the Belt and Road Initiatives]. Journal of International Relations, (06): 78-90 (In Chinese). http://www.1think.com.cn/ViewArticle/html/Article_4FFA4A807C07BCF4B4EF9BFBD2A90C8B_39185.html

Guan G. H. (2022). Thirty years of China–Russia strategic relations: achievements, characteristics and prospects. China International Strategy Review, 4(01): 21-38. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42533-022-00101-6.

Goodman L. W., & Schneider A. (2023). Conflict, Competition, or Collaboration? China and the United States in Latin America the Caribbean. In Aaron Schneider and Alessandro Golombiewski Teixeira, eds., China, Latin America, and the Global Economy, Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2023.

Junior O. B. (2010). A parceria estratégica sino-brasileira : origens, evolução e perspectivas (1993-2006). Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão.

Ko S. (2006). Strategic partnership in a unipolar system: The Sino-Russian relationship. Issues & Studies, 42, 203-225.

Liu H. L. (2015). From Alliance to Strategic Partnership: Connection and Differences. Indian Ocean Economic and Political Review, (05): 42-60 (In Chinese). doi: 10.16717/j.cnki.53-1227/f.2015.05.002

Li Q., & Ye M. (2019). China’s emerging partnership network: what, who, where, when and why. International Trade, Politics and Development, 3(2): 66-81. doi: 10.1108/itpd-05-2019-0004

Men H. H. (2005). Constructing a Framework for China’s Grand Strategy: National Strength, Strategic Concept and International System. Peking University Press (In Chinese).

Men H. H. (2009). Introduction to China’s International Strategy. Tsinghua University Press (In Chinese).

Maher R. (2016). The Elusive EU-China Strategic Partnership. International Affairs, 92(04): 959-976. doi: 10.1111/1468-2346.12659

Oviedo E. D. (2016). The Reality of Sino-Latin Relation. Journal of Jiangsu Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), 42(3). (In Chinese). doi: 10.16095/j.cnki.cn32-1833/c.2016.03.003

Portela C. (2011). The European Union and Belarus: Sanctions and Partnership? Comparative European Politics, 9, 486-505. doi: 10.1057/cep.2011.13

Qiu H. F., & Liang W. L. (2022). 中国–东盟全面战略伙伴关系中的合作外交 [China–ASEAN Cooperative Diplomacy within a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership]. Contemporary International Relations, 32(04): 100-119. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/xdgjgx-e202204006

Renard T. (2016). Partnerships for effective multilateralism? Assessing the compatibility between EU bilateralism, (inter-)regionalism and multilateralism. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 29(01): 18-35. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2015.1060691

Strüver G. (2017). China’s Partnership Diplomacy: International Alignment Based on Interests or Ideology. The Chinese Journal of International Politics, 10(01), 31-65. doi: 10.1093/cjip/pow015

Sun X. F., & Ding L. (2017). 伙伴国类型与中国伙伴关系升级 [Explaining the Upgrading of China’s Partnership: Pivot Partners, Broker Partners and Beyond]. World Economics and Politics, (02): 54-76 (In Chinese). Available online: http://ejournaliwep.cssn.cn/qkjj/sjjjyzz/2017nd2q_8212/201704/t20170407_4353715.shtml

Telias D. (2021). El orden liberal, China y América Latina. China y América Latina: claves hacia el futuro. Edición de Jorge Sahd.

Wang G. F., & Hu J. L. (2005). On Jiang Zemin’s Diplomatic Strategy of Partnership. Socialism Studies, (03): 122-124 (In Chinese). doi: 1001-4527(2005)03-0122-03

Weber K. (2007). Governing Europe’s Neighbourhood: Partners or Periphery?. Manchester University Press.

Wang Z. (2018). Great Power Diplomacy with Chinese Characteristics in the New Era: New Evolution and Characteristics of Partnership Diplomacy (2013-2017). Contemporary World and Socialism, (04): 167-175 (In Chinese). doi: 10.16502/j.cnki.11-3404/d.2018.04.021

Xie W. Z. (2019). Review on China-Venezuela’s Bilateral Relations in the 70th Anniversary of the P. R. C. Journal of Latin American Studies, 41(05): 19-41 (In Chinese). Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=smPsKIJgVaCRcaQAup2NjpuwR2N_v2jlL2MFQFSniUi3Vj0_HEDrs9LptEttYbGUUXhYdnGVcPKQ6cUxXWzzSEcX1qsekKeogKy9IUl7R3TscpFJ5UltQKuNkm5Czgq9nd3L2jN02ZZfwisldqKvSQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS

Xu Yanran. (2017). China’s Strategic Partnerships in Latin America: Case Studies of China’s Oil Diplomacy in Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and Venezuela, 1991–2015. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Xinhua. (2019). China, Suriname establish strategic partnership of cooperation. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-11/27/c_138587311_2.htm.

Yu L. (2015). China’s strategic partnership with Latin America: a fulcrum in China’s rise. International Affairs, 91(05): 1047-1068. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12397

Yu L. (2016). China-Australia Strategic Partnership in Context of China’s Grand Peripheral Diplomacy. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 29(02): 740-760. doi: 10.1080/09557571.2015.1119424

Zhao C. Y. (2014). 浅论20世纪90年代中国与巴西的战略伙伴关系 [An Introduction to the Strategic Partnership between China and Brazil in the 1990s]. Journal of Latin American Studies, 36(06): 60-65 (In Chinese). Available online: http://ldmz.cbpt.cnki.net/WKH3/WebPublication/wkTextContent.aspx?colType=4&yt=2014&st=06

Zhou Y. Q. (2016). When Partners Meet Allies: Interaction between China’s Partnership Network and U.S. Alliance System. Global Review, 8(05): 21-39 (In Chinese).

Zheng B. W., & Sun H. B., & Yue Y. X. (2009). Review and Reflections on the Sino-Latin American Relations 1949-2009. Journal of Latin American Studies, 31(S2): 3-17 (In Chinese). doi: 10.13851/j.cnki.gjzw.201605002

Zapata S., & Martínez-Hernández A. A. (2020). La política exterior latinoamericana ante la potencia hegemónica de Estados Unidos y la potencia emergente de China. Colombia Internacional, (104): 63-93. doi: https://doi.org/10.7440/colombiaint104.2020.03

1 Sun Yat-sen University, China. Researcher at the Center for Latin American Studies. PhD in Latin American Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. E-mail: zhangxiny@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

(*) Special acknowledgments to Garrett Thompson, Sun Yat-sen University (garrettbt@mail.sysu.edu.cn) for his professional support in the language proofreading of this work.

Fecha de recepción: 4 de abril del 2024 / Fecha de aceptación: 12 de agosto del 2024 / Fecha de publicación: 5 de setiembre del 2024

Revista de Relaciones Internacionales por Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional.

Equipo Editorial

Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica. Campus Omar Dengo

Apartado postal 86-3000. Heredia, Costa Rica