Esta carne mía: forma negativa y crítica afroamericana de la modernidad occidental

This Flesh of Mine: Negative Form and the African-American Critique of Western Modernity

Esta carne minha: forma negativa e crítica afro-americana da modernidade ocidental

Jonathan Pimentel Chacón[1]

jonathan.pimentel@gmail.com

Recibido: 15 de agosto de 2013

Aprobado: 11 de setiembre de 2013

Resumen:

Este ensayo trata de analizar algunos elementos necesarios para entender las formas en que el arte, la producción de Capital y el racismo se relacionan, particularmente en el contexto de los Estados unidos de América entre 1890 y 1930, entendiendo que la producción de Capital implica un proceso de racionalización que está vinculado a procesos de civilización, específicamente a constelaciones epistémicas. Dos conceptos de suma importancia para demostrar cómo el racismo y la producción de Capital están vinculados internamente son el consumo del cuerpo y maquinas con órganos, que a su vez son categorías centrales para entender como la relaciones entre representaciones visuales, forma, y producción de Capital son radicalmente criticadas.

Palabras clave: Producción de Capital, consumo del cuerpo, alteridad, racismo, colonialidad, postcolonialidad, subjetividad, visibilidad, carnalidad.

Abstract:

This essay tries to analyze some elements to grasp the forms in which art, Capital production, and racism are related, particularly within the context of the United States between 1890-1930, maintaining that Capital production implies a process of rationalization that is articulated with processes of civilization and, more specifically, epistemic constellations. Two concepts of basic importance are body consumption and machines with organs for they show how racism and Capital production are internally linked, and they are also central categories to understand how the relationship between visual representation, form, and Capital production, are radically criticized.

Key words:

Capital Production, body consumption, alterity, racism, coloniality, postcoloniality, subjectivity, visibility, carnality.

Resumo:

Este ensaio busca analisar alguns elementos necessários para entender as formas em que a arte, a produção de Capital e o racismo se relacionam, particularmente no contexto dos Estados unidos de América entre 1890 e 1930, entendendo que a produção de Capital implica um processo de racionalização que está vinculado a processos de civilização, especificamente a constelações epistêmicas. Dois conceitos de suma importância para demonstrar como o racismo e a produção de Capital estão vinculados internamente são o consumo do corpo e máquinas com órgãos, que a sua vez são categorias centrais para entender como as relações entre representações visuais, forma e produção de Capital são radicalmente criticadas.

Palavras chaves:

Produção de Capital, consumo do corpo, alteridade, racismo, colonialidade, postcolonialidade, subjetividade, visibilidade, carnalidade.

§. Introduction

The African American critiques of Western modernity from W.E.B Du Bois to Willie James Jennings[2] concentrated on, clearly with differences, how the black souled bodies have been physically and symbolically subjugated – although not completely- since the beginning of the institution of slavery throughout the present. The logic of enslavement, however, was not monolithic. As has been postulated, the slavery system has provided, through particular practices, libidinal compensations that guarantee the inscription of slavery domination throughout everyday life. By libidinal compensations, it must be understood that, together with its strict and cruel repressive practices the slavery system provides “supplements” that reinforce the joy of terror.[3] Hartman's analysis, as well as those by Du Bois, affirm that the period after abolition does not suppose a radical transformation in the African- Americans' life conditions. There is a continuity between the period before and after abolition that manifests itself in that which the Argentinian philosopher León Rozitchner denominates the capital of Capital: the modulation and weakening, through terror, of the deepest ground of ourselves, that which allows us to be with and for others: our constitutional carnality.[4]

Modernity, a historical and social process, takes place or inscribes itself in the Black bodies and, therefore, inscribes itself, as a part of the same trajectory, our bodies in an epistemic constellation that tends to unrecognize the density and truth of our own forms to inhabit the world. This ongoing process of dual inscription is constitutive to the modern hegemony of the commodity form. It acquires, however, particularities that are often missed. One of the most important is that the black bodies are considered, since the beginning and as a foundation of modernity, as specific commodity (machines with organs). This specificity introduces the question of form[5]; that is to say that while it is considered a commodity, black bodies are not the product of labor, so in order to rationalize – by this I am not implying a relation of pure causality or transparent intentionality- its commodification it was certainly fundamental to create and reproduce “the form of black bodies”.[6] Thus, my thesis is that the visual production – as a camp of conflict[7] - is both a neglected and basic access to the African-American critique of Western modernity.[8]

Modernity's incarnation on the black bodies has implied the displacement of a plurality of places of enunciation (forms to tell the world and present oneself) as well as rhythms, forms, and to use a Du Bois' notion, have destroyed or concealed part of the beauty of the world. However, the dual process of concealment and over-exposition of black souled bodies[9] is not a closed totality; it has been possible to create and extend immanent fissures, ruptures and displacements that have been introduced, through a negative form, a radical critique of modernity. Following this argument I would like to analyze the African-American visual arts[10] (from Elizabeth Catlett to Aaron Douglas -Harlem Renaissance[11]) as an expression of negative subjectivity. These visual arts often point beyond the hegemony/fetishism of the commodity form and relatively disrupt the domination of Black bodies within Western modernity.

§.1. Western Modernity, Capitalism and Negative Subjectivity

In his Grundisse Marx criticizes the concept of independent individuals as was understood by, among others, David Ricardo and Adam Smith. Marx's critique contains three different aspects. 1) According to him there is no rupture between society and individuality. Thus, the manifestations of modes of individuation are not independent from their social conditions of possibility. This mutual belonging implies that every mode individuation possesses a history and is susceptible to being transformed. Marx's thesis is that in order to grasp the character of a subject it is necessary to understand the specific processes in and through which these individuals manifest themselves. This first aspect of Marx's critique concentrates on the materiality of any mode of individuation. Nonetheless, his critique refers particularly to the thinking according to which the individual (a notion that combines the idea of a complete/autonomous self-production, the primacy of the private property owner and what A. Arendt called “world alienation”[12]) was the natural state of the human being. Hence, Marx's critique procures a non-ontological understanding of human practices as well as a non-natural understanding of history. For Marx the permanent transformation of societies and regions does not follow an ideal logic or Geist; however, he sustained that it is possible to grasp the constitutional logic of Modernity through the analysis of its organization of a complex social division of labor.

By natural understanding of history, Marx also refers to the locus communis which postulates that particular modes of individuation – that arise within modernity- represent a closure of the time.[13] 2) The other aspect of Marx's critique is related to his concept of production. With this concept it is explained, at first sight, that the core of modernity are social individuals. Therefore, in order to grasp the tendencies and flux of its process it is required to introduce, in every social theory, socio-historical delimitation. Thus, in an epistemic fashion Marx uses the concept of production in order to highlight that every production's process is bound by social individuals. Also, he uses the concept to designate a specific form of production (not just economical), namely modern bourgeois production. I shall mention that this clarification made by Marx about the specificity of his analysis has two major implications. First, that his critical theory concentrates on the concrete forms of social domination that are specific of capitalism. When Marx introduces the concept of production he is thinking about forces of production and relations of production[14] at the same time. This distinction does not imply that Marx separates the sphere of production and the sphere of distribution, on the contrary what it implies, as has been pointed out by Moishe Postone, is that for Marx the overcoming of capitalism supposes the transformation of production. That is, in its last consequence, the abolition of value. Second, production designates in this analysis a form in which capitalism extends itself throughout the social relationships and is institutionalized.[15]

Marx's critical theory incorporates a concept of production that implies: “[The] Appropriation of nature on the part of an individual within and through a specific form of society”[16] as a very basic characteristic. Production, therefore, refers to a total process in which particular forms of individuation are possible and necessary. 3) There is a question that Marx notices which constitutes a problem in itself: the relationship between relations of production and legal relations. He specifically said “But the really difficult point to discuss here is how relations of production develop unevenly as legal relations”.[17] This clearly is related to two themes previously mentioned: the naturalization of modern production by bourgeois thought as well as the same notion of production as total process. However, this mention introduces a new element in his criticism: the deepest operation of modern production locates itself in what it is adequate to call permanent self-referentially. This is one of the primordial levels of Marx's critique. By permanent self-referentially I designate three questions:

– Capitalism does not imply a simple negation of history or of its own historical conditions of possibility. It creates a particular historicity; furthermore, it inaugurates a history that tells itself in its own development. It is a movement -that understands itself- without exterior. Thus, production within capitalism, as Theodor W. Adorno has commented, is imagined as an infinite movement, that expresses an irrational rationality.[18] Capitalism is a false universality because it negates its own contradictions. This negation includes the legal use of violence. This violence, however, is not just restricted to the “legal sphere” rather it expresses itself in the form of mythical, cosmological, epistemic and cultural violence.[19]

– If there is a relationship between (the imagination of) infinite production and legal violence within capitalism it is expressed not as residual. Recent studies[20] demonstrate that it was necessary for Western capitalism in order to expand itself – to follow its own identity- to complexly increase its rationalization. Analyzing primordially the experience of Taylorism, G. Lukács affirms that:

With the modern “psychological analysis of the work-process (in Taylorism) this rational mechanisation extends right into the worker's “soul”: even his psychological attributes are separated from his total personality and placed in opposition to it so as to facilitate their integration into special rational systems and reduction to statistically viable concepts.[21]

Lukács' analysis of rationalization – and attempt to bring together Marx and Weber – is strictly focused on the rationalization of the work-process. In the core of his analysis, he said, “We are concerned above all with the principle at work here: the principle of rationalization based on what is and can be calculated”[22], thus, Luckás argues that the increasing specialization and abstraction of the labor process produces a radical rupture in the worker. The analysis, therefore, maintains that Capital production, at its core, supposes, as its condition of possibility, the accumulation, fragmentation, and reduction of human creative energy. Even if Luckás' analysis adequately discusses rationalization as a process that increases irrationality, the notion of rationalization that constitutes the nucleus of Capitalism could be considered more complex.

– A text like Essai sur l' inégalité des races humaines by Arthur Gobineau[23] or the creation/concealment of the other in Western philosophical thought[24] are expressions of a broader and deeper notion of rationalization. When Gobineau affirms that “the negroid variety is the lowest, and stands at the foot of the ladder. The animal character, which appears in the shape of the pelvis, is stamped on the negro from birth, and foreshadows his destiny”[25], it’s not expressing some isolated deviation from Western rationality. Furthermore, as Cedric J. Robinson has displayed, positions like those of Gobineau's are a fundamental feature of Western capitalism.[26] The “science of race” and “metaphysics of form” in which the Essai is grounded is also expressed in the United States in a wide variety of cultural products.[27] Gobineau's highlighting of the alleged lack of rationality of the “negroid” is not an individual prejudice, as Marx himself recognized[28], it is part of the epistemic constellation that dialectically relates to Capital production/ rationalization.

Marx's critique of the bourgeois' notion of individual shows that his analysis of capitalism is an attempt to grasp the internal and immanent logic of a process that reconstitutes the world. In this sense it is possible to argue that Marx's project includes a radical critique of the ongoing civilization process[29] which, I argue, in the case of the African and African-American slavery, colonization, and, in the “postcoloniality” is fundamentally a process of body consumption. In being so, it implies that its own movement constitutes the destruction of a whole of various and different forms to dwell in the world.[30]

The concept negative subjectivity designate the possibility that through complex and irregular processes it is possible to situationally and/or structurally produce ruptures within the everyday production and reproduction of Capital. The positive subjectivity of the commodity, which implies the global extension of the mercantile relations, is related to the invention of the individual. Marx is not only interested in “the individual” as a positive expression of subjectivity, but with its negativity, that which is marginal or transcendental to the expansiveness of Capital. By the notion transcendental our own relative possibility to overcome our own productions and to transform its ambiance is implied. To that process and possibility I refer to as negative subjectivity. Therefore, the institutions, symbols, art and religion produced in Modernity are not just the positive representation – or form of rationalization- of the mercantile relations, but they also could include its negation. That is to say, they could contain and express alternative forms of social relationships.

§.2. Body Consumption, Civilization and Visibility

The consumption of African and African descendent bodies was foundational for Capital production; it functions as a primitive accumulation. Explaining the “Secret of Primitive Accumulation” Marx argues that:

In themselves, money and commodities are no more capital than the means of production and subsistence are. They need to be transformed into capital. But this transformation can itself only take place under particular circumstances, which meet together at this point: the confrontation of, and the contact between, two different kinds of commodity owners; on the one hand, the owners of money, means of production, means of subsistence, who are eager to valorize the sum of values they have appropriated by buying the labor-power of others; on the other hand, free workers.[31]

In Marx's analysis a free-worker is the one that is able just to sell his or her naked body as a source of value. Marx's conclusion regarding primitive accumulation is that “So-called primitive accumulation, therefore, is nothing else than the historical process of divorcing the producer from the means of production”.[32] I shall argue that Marx's argument in this regard is incomplete if it is approached from the relationship between slavery and Capital. From this approach Capital is constituted by a cosmological exile, linguistic rupture and carnal alienation. Willie James Jennings' analysis of the consumption of African enslaved flesh and Western imperial enterprises are inseparable.[33] The historical fact that on August 8, 1444 – in the presence of Prince Henry of Portugal, the Navigator – there was a massive over-exposition of enslaved African bodies with the displacement that such an act implies re-opening for us the core of primitive accumulation. Being transported from different places in Africa to the coast of Cape Blanco – or to the territory of the United States- signified for the enslaved to be not only separated from the means of production and subsistence of their own life: they were relatively subsumed by Capital. Therefore, they were even separate from themselves as “souled bodies”.[34] This separation, in the United States, will later acquire geographical and spatial dimensions that are formative for the reproduction of Capital and White Civilization.

Cosmological exile: the organization of the World that the Western capitalism procured to impose on the enslaved included a negation of the universal possibility to be differently human.[35] That is to say that the Imperialistic process procures or is animated by a desire of closure. The champ of references that were brought with the enslaved was sanctioned as structurally deficient. Jennings adequately affirms that: “The languages of the enslaved will be bound to the languages of the Europeans, as peasant to royalty, as the lesser to the greater. Unknown tongues will be overcome not by a surprising linguistic act of God, but by energies of market and nation-state”.[36] This author pointed out the totalizing process in which slavery is inscribed and through which it is reproduced. Language, market and nation-state constituted the meta-language of Western Civilization. If the cosmological exile implied the violence toward the sacred ground upon which the modes of being in the world of the enslaved were founded, the linguistic rupture makes the entire access to their bodies as pure machines with organs possible, which implies the vanishing of the body as epistemic and sentient locus. Jennings interprets this in theological and cosmological terms saying that “In this horrific scene African's body indicates the ultimate victory of death. The holy use of Jesus' body – the one who became a slave to die as a sinner for humankind- parallels the separation of slaves into lots for Portuguese servitude”[37] Western imagination is exposed for Gobineau's following description:

All food is good in his eyes, nothing disgusts or repels him. What he desires is to eat, to eat furiously, and to excess; no carrion is too revolting to be swallowed by him. It is the same with odours; his inordinate desires are satisfied with all, however coarse or even horrible. To these qualities may be added an instability and capriciousness of feeling, that cannot be tied down to any single object, and which, so far as he is concerned, do away with all distinctions of good and evil. We might even say that the violence with which he pursues that has aroused his senses and inflamed his desires is a guarantee of the desires being soon satisfied and the object forgotten. Finally, he is equally careless of his own life and that of others: he kills willingly, for the sake of killing; and this human machine, in whom it is to easy to arouse emotion, shows, in face of suffering, either a monstrous indifference or a cowardice that seeks a voluntary refuge in death.[38]

The “negroid” is, for the French author, pure reality[39], a naked present phenomena or mere physicists.[40] As Hegel remarks the only physicists are the animals, Gobineau nonetheless does not use the term animal to characterize the “lowest of the races”; rather he uses the notion of human machine, which forms part of the same semantic field as the notion of machines with organs. Marx in Capital II observes that: “The means of production are no more capital by nature than is human labour-power […] labour-power operates only as an organ of capital.”[41] As Marx's notion of surplus-labour designates the consumption of the worker by Capital, the notion of machine with organs refers to the process through which Capital production incorporates an epistemic register that is not simply exclusive or discriminatory. Moreover, it pretends to “swallowed” within itself all its different “components” sustaining a hierarchical “scientific” and metaphysical structure.

The “lowest” race is not excluded from Capital production but is assumed as its organ, its degraded physique or blood; while the “white peoples” are the Spirit of Civilization. Gobineau explains: “The immense superiority of the white peoples in the whole field of the intellect is balanced by an inferiority in the intensity of their sensation […] is less tempted and less absorbed by considerations of the body, although in physical structure he is by far the most vigorous”.[42] I shall refer to the fundamental relation that this corporeal imaginary has to Capital production as had been explained through the notion of Civilization. However, before entering into that discussion it is important to highlight that even if the consumption of black bodies responds to different and interconnected registers, it is possible to refer to it as a type Bio-capital[43]. The beginning, or more precisely a stage in its constant transformations, of what Kaushik Sunder denominates technoscientific capitalism, is precisely the contextual relationship between Western Capitalism and the manipulation of life through the Imperial enterprises and the sciences/metaphysics of race. Hence, Capital production contains within itself a politics of life itself[44].

Civilization is a concept and judgment of value that, for Norbert Elias, is referred to as technisation and power. Elias' explanation of technicization as “the process by which, as it progresses, people learn to exploit lifeless materials to an increasingly greater extent for the use of humankind”[45] does not take into account that as articulated with Capital production, civilization is not just articulated with the use or exploitation of “lifeless” or raw materials, nor with the pure exploitation of human life. Rather, it refers to a large corpus of intelligibility or horizon of sense that allows the manipulation of life. What is important to acknowledge in Elia's notion of technicization is that it recognizes that it is an unequivocally corporeal process. That is to say, that it supposes not just a “better life” but the modification of the body through the increasing efficiency regarding the control of the “environment”.

While Elias maintains that “the process of civilization is related to the acquired self-regulation that is imperative for the survival of a human being” and then continues saying that “Without learned self-regulation a person is not in the position, without great discomfort, to defer -in accordance with realistic circumstances – the fulfillment or urges he or she pursues”[46]. But, he does not refer to the fact that the fantasy according to which the infinite production of commodities is possible[47] – that contradicts his idea of the process of civilization – and the regulation of the other – the degraded blood of Capital – appears inseparable from each other. In other words, he does not take into account a “genetic” contradiction that is at the core of the Western process of civilization.

The unregulated desire of the commodity fetishism or the immanent asceticism of Capital production, as explained by Weber, contents in the West a global regulation that radically interferes with the existence of multiple processes of civilization. Elias affirms that “There is not fundamental sphere in the development of humankind that forms the basis for all others. The Alpha and the Omega of this development are human beings- or indeed humankind itself”[48], the case is that even if one agrees with Elias in its normative statement it is still phenomenologically insufficient. His own analysis, nevertheless, implicitly incorporates an important insight when discussing the multiple forms in which transportation “of goods and people was one of the greatest and most far-reaching scientific- technological changes that took place in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries”[49]. This irruption of new means of transportation allows for not just a temporal and spatial rupture but the expansion of particular civilizing processes. These processes acquire part of their universality through scientific- technological changes, hence they are inscribed in the wide appropriation of the visibility and invisibility of the world by Western imperial enterprises. The coexistence of different processes of civilization, with their particular historicity, rhythm and projections had been differently broken or deeply affected by the incrementation of technoscientific power in the West. Thus, even agreeing with Elias' reserves regarding schematic approaches to historical movements or changes, I shall argue that the processes he describes are not merely occurrences without attachments to its own time.

The latter is recognized even by Elias when he affirms that “The civilizing process is a process of human beings civilizing human beings,”[50] but his declaration still is general. In his essay “Power and Civilization”[51] the author explains that the process of civilization in industrially developed countries generally implies the decreasing of violence and the desire and possibility to co-exist based on respect and mutual responsibility. This process, therefore, is bound by self-constraint and individual agency. Elias' description initiates with the following assertion that affirms that in the Western process of civilization “people identify to a greater degree with other people, even those less powerful, is becoming clear especially in our time”[52], hence the process of civilization of which Elias is thinking when explaining his position is twofold: decreasing of violence and increasing of self-constraint.

Elias ignores that there is a forgotten and foundational violence that shapes the process that he was trying to understand. It is precisely this dismissed violence which is at the core of what this author understood as the basis for human pacification: the modern state formation. The manipulation of the enslaved – the decision about their life -, their use as machines with organs, and their over-exposition as the complete exterior of the West is not estranged to the transformations that accompanied the rise of the Modern state. Furthermore, its institutions were partially produced and reproduced to sanction the rationality of the terror, terror toward the territories of the others.[53]

Visibility

There are several instances through which the question of the visibility of the Black bodies possesses a fundamental character in the total process of Capital production. I shall delimit the following discussion to the case of the United States from the second part of the nineteenth century to the first quarter of the twentieth century. African-American interpretations[54] of the question of Black flesh visibility are being produce from different perspectives and interests. However, among these projects it is possible to identify the attempt to create a strategy to critically read the specific visibility of Black flesh and also to question the forms in which it is created, narrated, linked to its own historical roots.[55] These different analyses engage the question putting relevance on gender, sexual, cultural, geographical and religious aspects. Their disparities as well as their commonalities show that this has been a basic issue in African-American critical thinking during the last few decades. Discussing some epistemic features of these discussions constituted the first moment in this part. The second part presents and discusses effective representations of African-Americans through painting and does so within the temporal framework previously mentioned.

As I mentioned in the previous sections of this essay, Western Modernity is a historical process that focuses on, among other aspects, the consumption, production and “scientific” modulation of Black bodies. I argued that this focalization is a foundational determination of Capital production and its rationalization.[56] La dynamique du capitalisme[57] makes place and requires a special mode of visibility that is expressed through different means that are part of a common and flexible epistemic culture.[58] Alesandra Violi's thesis according to which: “l' esperienza della modernità viene rappresentata come un gesto violento che disseziona la forma umana. L´immagine del corpo anatomizato e ridotto in frammenti si ripropone in effeti come una constante nell´estetica del moderno”[59]. Violi's study shows how the occupation of the body for scientific reasons has been a primary motive of modernity's imagination of the human as an object or territory of exploration. Being able to make visible (to constitute it as an object) the presence of the other requires a long process that is composed by modes of knowledge, its institutions, and modes of apprehension.[60] The dominant epistemic constellation of Modernity is inseparable from the kinds of individuation that are dialectically constituted by Capital production. Regarding the discussion of visibility this means that there are processes that enable a form of visibility that turns into commodity and, at the same time, produces the sentiment of invisibility among some African-Americans.[61]

In Capital, Marx argues that: “Commodities cannot themselves go to market and perform exchanges in their own right. We must, therefore, have recourse to their guardians, who are the possessors of commodities.”[62] He is referring in this passage to the subjectivity that is expressed in the process of commodity exchange. In Marx's perspective even the wage-workers expressed this subjectivity when willing to exchange their own body in order to acquire their means of subsistence. But Marx's analysis does not, for historical and theoretical reasons, consider the form of exchange that supposes even the negation of this subjective of the “private property owner”. In the case of the slave trade and exchange what appears is the (fantasy) of the transparency/pure visibility of the machine with organs. The owner of private property represents him or herself through the mediation of the social representation of owners. This positive subjective contains in its visibility the reminiscence of a nucleus of invisibility that remains inaccessible. But, the exposition of Black bodies at the slave market/exchange pretends to show everything -as the desire explained by Violi is to get access to the matrix of the life through the dissection of the cadaver – in order to exchange it. The Black bodies became strictly an object (with organs) that could be measured, weighed and furthermore approached “scientifically”.

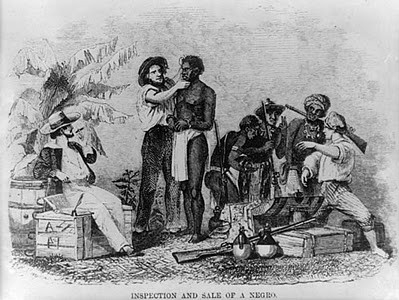

The image above[63] includes the inscription “Inspection and Sale of a Negro” which brings together the intrinsic relationship between knowledge and Capital and also functions as a certification for the reality of what was happening. In the image one of the traffickers is measuring the skull of the African person. This practice, grounded on a multiform politic of the life itself, was common during the nineteenth century and even during the first decades of the twentieth century in the United States. The “Crania Americana”[64] had the purpose to seek the exact potentiality of the commodity as well as to reiterate the complete control under which the enslaved was. Phrenology was in this extent on one side “a physiological rationalization for the global empire”[65] and on the other side “offered an explanation and a language that turned conquest into scientifically determined inevitability”[66].

The fantasy remains: going into the profundity of the body – to its same constitution- becomes not just possible but also confirms that the effective or created anatomical differences are unavoidably linked to social and political destinies. As the image shows the seeking of visibility is inscribed within the exchange/trade which is, at the same time, subsumed by the global expansion of Capital production. But the image itself has its own productivity, it communicates a historical fact rather than just containing and expressing the past, it extends itself toward the future.

Through the exposition of the image it is predicate the irreversibility of the occurrence as far it is “pure fact”. The image appears as completely untied with historical determinations, that is to say, as an encounter of history and reason. The corporeal disposition of the “scientific” traffickers and that of the enslaved reinforces this interpretation. The two white men are sovereigns -the same image is sovereign- as far as their power over the bodies in the image does not even need legitimation. What kind of power is this that does not require the legitimation of a matrix of power? I shall say that the sovereignty expressed through the image is allowed by the dissemination of a particular kind of knowledge that is able or has the faculty to decide over life and death. Furthermore, this knowledge can, with exclusive reference to its own determinations, establish the limits of aliveness of specific lives. At the same time, this knowledge is supported by a more archaic spiritual production, that in the longue durée of the Western history, remains an integral part of the anthropological imagination that is being discussed here. Previous to every biological reduction or science of race is the anthropology/cosmology that created an abyss between body/flesh and soul regarding non Aryan races. The rhetoric that justifies the subjugation of the “negroid” because of his/her carnality found decisive support in the early rejection of flesh and its desires (actus) as opposed to the ens realissimum.

Form and the metaphysics of the visible

Marx's analysis admits that “The difficulty lies not in comprehending that money is a commodity, but in discovering how, why and by what means a commodity becomes money.”[67] The question that I had put here into discussion is how, why, and by what means human flesh becomes commodity (machine with organs). I would like to, as an initial stage of resolution to this question, explore what could be called a "metaphysics of form" that can be characterized as “a theory that refers much more to Plato than to the laws of genetics; that believes much more in the strength of a self- conscious myth than in scientific discourse; that is, a theory that knows perfectly well that the effectiveness of race lies in its mythical and transfiguring force”[68]. Metaphysics refers in this exposition to a mode of thought that accentuates the spiritual/somatic superiority of the Whites people – or Aryan in Gobineau's language – in comparison with other races. As was already referred to, in Gobineau's schema the white people's physical structure is “far the most vigorous”. This feature, besides that of intellect of spirit superiority, is completed by honor. For Gobineau it is almost unnecessary to mention that the word honor – and the Weltanschauung that serves as it signifier- is unknown to both “the yellow and the black man.”[69] Spirit/intellect, somatic perfection, and honor are indissolubly connected.[70] Spirit is the realization of the reason, its self-identity or the encounter with its essence. There is no rupture or distinction between “white peoples” and reason. This encounter is manifested or expressed through the body or, more precisely, to their physical superiority. Reason incarnates itself in “white peoples” and this implies a reconfiguration of white people's strength. Their body makes visible the beauty and power of reason (the Idea or original Form), but this body rather than just being individual is also a political and cultural body, a civilization[71]. This concept introduces, in Gobineau's presentation, different characteristics such as language, social and political organization, and so on. The identity of each civilization depends on several factors; among the most important factors are blood and geographical extension.

Regarding the first factor, it is fundamental to say that the “mixture of bloods” was one of the most important concerns for authors like Gobineau because it supposes, as a rule, the decreasing of the best characteristics of the white race and degeneration.[72] Since the non-Aryan civilizations are inferior it is plausible that the Aryans would have the right to expand, as the free movement of reason, their civilization there were “stagnation supervenes”[73]. Honor expresses itself in the closure of the race and, at the same time, in its spatial extension. This extension is signed by a historical imagination that is adequate to call the return to the roots. Returning to the roots clearly requires creating them and that is done in Gobineau's genealogy of civilizations. He emphatically insists on the idea that when any “minor” civilization produced or expressed some valuable product it was caused by the influence of Aryans. Hence, returning to the roots, in this genealogy, comports the unification of all the Aryans that are united by Spirit, beauty/strength, and honor. Unifying the race, regardless of its internal dissimilitudes, is the labor of the Spirit (and the ancestral hero[74]) and also its artistic creation. This unification is also thought to undermine – and until some extent to overcome- the “liberal dogma of human brotherhood”[75].

The Aryans are constituted by blood, a frontier that could be not trespassed. Gobineau's criticism of Christianity is intimately connected to this “metaphysics of form”. While recognizing several positive aspects of Christianity, the author also criticizes its lack of power to produce a propagate civilization, meaning by that the inability to embrace, as rational, the expansion of white people civilization. As far as unification requires extension and homogenization the type of universality expressed by Christianity is insufficient. Universality, as was thought by this author, has a historical matrix and telos: the pristine self-manifestation of the authentic human civilization throughout the world. Following this, race “[...]is in fact not assumed, naively or instrumentally, to be a biological and factual datum, but rather a Platonic idea that gives shape and brings order to the chaotic world of appearances. Race thus becomes a phenomenon perceived by our senses as an expression of the soul”[76] Just if the race of the white peoples extend and purify itself from previous degeneration it is that Life itself can prosper and express itself. Race is not a mere biological fact, merely material or natural, but a blood heritage, which means continuity between the ancestors and the present. Such continuity is precisely the means through which the blood/honor is historically conserved.

Regarding art representations I shall aggregate to that what I already mentioned that “metaphysics of form” expresses itself through art or, more exactly in visual presentations, basically emphasizing the absence of soul (spirit) or ideal form (the strength of Aryan beauty). The following image presents the former expression of “metaphysics of form” through what Hartman calls “innocent amusements and spectacles of mastery”[77].

The image above[78] contains the following inscription: “Man of Color. Ugh! Get out. I ain't one of you no more. I'se a Man, I is!”[79]. Even Gobineau, until some extent would qualify the image as “unhappy” due to his notion of imitation, however important the comment is, first, that the image shows that even the animals were looking with amazement at the young boy. He does not belong simply to the animals; he expresses another form, one more degraded. He lacks, as his use of English language pretends to prove, the intellect/spirit. His same proud results, in its most elementary level, absence of honor and impurity of blood.

The “I” expressed in the phrase “I is” allows the racist reader to confirm the inhumanity of the Black boy and as a part of the same trajectory to re-affirm his/her superiority. Nonetheless, this is just a first level of significance. The next level refers as well to the “free act of speech” that the boy performs in the image. This act of speech is, as represented through the image, a spectacle of mastery. It is a form of subjection – to production of subject- as well as the sign for an irreparable damage: that which is expressed in the same appearance of the boy. What the image sought to do is to turn the apparition of a Black body as equal to spiritless and formless. So, its intentions are deeper than just to produce a subject; rather than an individual what is represented is the impossibility of a black humanity.

J. Lacan observed, in relationship with the formation of subjectivity, and its attachment to the symbolical order that: “Car ce qui est omis dans la platitude de la moderne théorie de l’ information, c’est qu’on ne peut même parler de code que si c’est déjà le code de l’ Autre, or c’est bien d’ autre chose qu’il s’agit dans le message, puisque c’est de lui que le sujet se constitue, par quoi c’est l’Autre que le sujet reçoit même le message qu’il émet”.[80] The formation of subjectivity requires violence in the form of subordination to the symbolical order. Nothing, even the language he acquires since its childhood and which allows it to participate with “sense” in a particular social formation, belongs to him (the Boy in the image). Being a subject is, therefore, to be placed in a context of permanent flux of power, condensed and manifested in language, which passes through the subject’s body, cutting it. The logic of the different “language games” is violent in the sense that they, in order to control the anomalies, delimit the possibilities of significance.

The subject is always lacking or missing something. It is intrinsically unable to produce or recover, through the act of symbolization, its own “identity”, the specular image of the mirror stage. In Lacanian theory there is always a confrontation between the subject and its symbolical identifications; this instability is permanent. The violence I am referring to here is that of normalization. In order to maintain its identity the subject must procure stabilization or repress its residual “psychic life” to coincide with the rules of the symbolical order. But, as Lacan insists, that coincidence is not possible or at least not desirable. The subject is a series of cuts and the lack will always remain. In the case of the image discussed here the conclusion is even more radical: is there no form to fulfill the socio - symbolical order? Is there, in this sense, no path through which the black boy could be normal? Not even that of imitation?

§. 3. Negative Form, art and carnal ethics

W.E.B Du Bois' analysis in his Black Reconstruction[81] and in the essay “The Study of Negro Problems”[82] are important to situate African-American art within the United States’ Capital production. The problem of the color-line forms part of the total process or trajectory of United States’ civilization. In this regard the “Negro Problems” are organically attached to the construction of the country's sociability. As Du Bois explains in the end of the nineteenth century the situation of the Negroes was marked by two fundamental characteristics:

First, Negroes do not share the full national life because as a mass they have not reached a sufficiently high grade of culture.

Secondly, they do not share the full national life because there has always existed in America a conviction - varying in intensity, but always widespread-that people of Negro blood should not be admitted into the group life of the nation no matter what their condition might be.[83]

The first question referred should be read in two complementary forms. First, the allegation about the lack of culture, as had been established previously, functions or acts as a decisive aspect within the “metaphysics of form”. Du Bois' reference to the problem of the lack of culture is, as he shows it in The Souls of Black Folk, a critique of the American racist socio-symbolical order. However, he is also arguing that, as a result of the social relations of domination, the Negro effectively lacks “capitals” to fully develop his/her beauty. The situational and structural discrimination creates structural impediments for the progress – to use Du Bois' language – of the Negro. The second question, clearly related to the discussion of the “metaphysics of form”, whose purpose is none other than to put into radical criticism the notion of freedom and democracy that was hegemonic in the transition toward the twentieth century. Nonetheless, the mention of “blood prejudice” allows one to point out that the conjunction of economy, culture, and knowledge, as posed by Du Bois, does incorporate the acknowledging of the centrality of visual representations as part of the mechanisms of social domination. Within his criticism, Du Bois desires to make possible that the negro expresses his/herself as an artist.[84] His understanding of “Negro art” contemplates three[85] thematic fields or nuclei: 1) tradition and recollection, 2) beauty and flesh, and 3) ethics of art and recognition. As a general remark, it is necessary to say that for Du Bois art is a form of becoming. It does not express a full or final identity or essence; rather it is a way to manifest the ambiguities that are resultant of “To be and Not to be”[86]. What is important for Du Bois is the process, art is both an affirmation and negation or, to put it differently, it contains in itself its own negation. This is clearly important because it opens an alternative notion of form. In this regard the following affirmation results determinant: “That somehow, somewhere eternal and perfect Beauty sits above Truth and Right I can conceive, but here and now and in the world in which I work they are for me unseparate and inseparable”[87]. While the text leaves open the possibility of an Ideal form (Beauty) – but without identifying it with a specific race – Du Bois, rather than embrace a “metaphysics of form”, affirms that beauty is historically understood, beauty is also particular and manifests itself partially and universally in all fleshes: “Such is Beauty. Its variety is infinite, its possibility is endless. In normal life all may have it and have it yet again”[88]. Phenomenological forms, for Du Bois, do not refer themselves to an original One. In order to reach perfection, on the contrary in their condition of becoming, become themselves through their social relationships. In other terms they do not become an essence but their own trajectories.

Tradition and recollection

Thereis a dialectic in Du Bois' presentation between the past, present, and future. While affirming that “We black folk may help for we have within us as a race new stirrings; stirrings of the beginning of a new appreciation of joy, of a new desire to create, of a new will to be”[89]. He insists in that “Negro Art” should recollect -be the memory of the death- the pain, suffering, struggles and incomplete promises of the past. The response to the past is an integral part of an epistemological gesture that is found in the untold history of the victims, in the grotesque and abject, the unstable ground upon which it could express itself. Recollection designates an attitude that is not afraid of death nor gives name to it, to express its concreteness. It is convenient to quote Du Bois in order to appreciate this dimension as is exposed by himself:

I once knew a man and woman. They had two children, a daughter who was white and a daughter who was brown; the daughter who was white married a white man; and when her wedding was preparing the daughter who was brown prepared to go and celebrate. But the mother said, “No!” and the brown daughter went into her room and turned on the gas and died.[90]

These are the sources for the “romance” of “Negro Art” according to Du Bois. As an art that procures to be an expression of the becoming of a race it cannot be purely contemporary or actual. It has to maintain a critical distance with its immediacy, it has to return to the graves, to the forgotten landscapes that still retain/conceal the “brown daughter”. As a result of this “archeology” or “geology”, the artist is impulsed even to appropriate the “common sense” of the racist everyday life. In doing so, he or she destabilizes the “color line” being able even momentarily to leave without effect the power of the “metaphysics of form”.

The images above[91] produced by Elizabeth Catlett are a manifestation of recollection as it insists in presenting again a black man and black woman not just as past but as an unexpected irruption from the borders of our collective memory. In “My Reward” is a laconic piece that expresses, without being excessive in its details, a silence that screams to us the unrecognized sufferings that are still claiming for justice. The man in the painting resists looking at us, his eyes are looking somewhere else, perhaps pointing to others that had been forgotten or to another direction beyond the barbed wire. That is to say, beyond the situational and structural conditions in which the landscapes are for all of us. Catlett's portrait of Sojourner Truth presents evident differences in comparison with “Separation”. The most evident is the presentation of the body. Truth appears strong; her hands are big and firm. Her eyes are looking at us and, at the same time, pointing beyond us. The body of a black woman, in this case, rather than being a metaphor for freedom, justice, or strength is in itself all of that and even more: it is the notion of infinite beauty introduced by Du Bois. The artist's gesture is disruptive since she does not avoid returning to a woman's black body in order to affirm her own being in the world. There is clearly a conscious election in Catlett's representation; she does not return to a dead Sojourner. It is precisely this election that constitutes a matrix for recollection, because for the “metaphysics of form” there is nothing that could be found in the body of a black woman. Catlett indeed found her flesh.

Beauty and Black Flesh

Du Bois' understanding of Beauty is that even if beauty appears universally it is a requirement for “Negro Art” to show the particular beauty of black flesh. Following the previous consideration, it results that all art is propaganda. Du Bois remarks that “[...] all art is propaganda and ever must be, despite the wailing of the purist. I stand in utter shamelessness and say that whatever art I have for writing has been used always for propaganda for gaining the right of Black folk to love and enjoy. I do not care a damn for any art that is not used for propaganda”[92]. The “aura” of the art is grounded on flesh's pleasure. Ultimately art is not an end in itself; it is always part of the political struggle that seeks to recover one's flesh. Therefore the beauty of art is manifested outside it or, more exactly, in its articulation with its own conditions of possibility. This is not an instrumental understanding of art; rather it is a relational/social comprehension of its “nature”. Any form of art is dialectically constituted; hence it follows a non-rigid logic.

Aaron Douglas' pieces[93] relate the pleasure of flesh with the African ancestors – a form of recollection- and with an ironical reading of the religious tradition. In “The Prodigal Son”, Douglas rather than embrace the idea that linked pleasure with sin – separation from God – he creates a genealogy for the Black flesh's pleasure that has important theological resonances. “In an African Setting” shows a communal dance – perhaps a ritual practice – in which the center is the movement, exposure and joy of the flesh. The painting tries to follow the flesh's rhythm, especially that of the couple dancing in the midst of the others. It is significant that the faces become almost irrelevant in this representation, a possible reason for this is that the apparition or manifestation of the other is not, for Douglas, localized or focally concentrated rather it is disseminated throughout the flesh. As Maurice Merleau Ponty affirms: “On ne peut étuder le corps comme on étudie une chose quelconque du monde. Le corps est à la fois visible et voyant. Il n'y a plus ici dualité, mais unité indissoluble. C'est le même corps qui est vu et qui voir”[94]. Douglas' “In an African Setting” expresses this “unité indissoluble”, that among other aspects is clearly opposed to the socio-symbolically produced “machine with organs”, concentrating his exposition in the becoming of movement.

Titling his piece “The Prodigal Son” is quite significant, especially if one establishes the continuity with the previous piece. What is suggested is a certain rupture with the discourse of the Other that comes from certain expressions of Christianity, those that sanction flesh's pleasure as constitutively “sinful”. Du Bois makes an observation that explicitly touches this aspect: “We are ashamed of sex and we lower our eyes when people will talk of it. Our religion holds us in superstition. Our worst side has been so shamelessly emphasized […] in all sorts of ways we are hemmed in and our new young artists have got to fight their way to freedom.”[95] Thus it is not insignificant that Douglas offers a celebration/recollection of both the tradition of the African ancestors and the abject performance of the Prodigal Son. In so doing it rejects the identification of Black that comes with Christianities, but also opens or “fights for the freedom” to create an epistemic space to embrace the Black flesh. In this sense what Douglas does is a powerful gesture: he assumes, without guilt or hesitation, all shame; canceling somehow its effects

Ethics of Art and recognition

At the core of Du Bois' discussion of “Negro Art” there is a carnal ethic. It follows the understanding that as propaganda for the pleasure of the Negro – which is, for him, always social and structurally disruptive – art has a moment of radical negativity. This negativity is related to a call for invisibility or rejection of transparency. While Du Bois affirms the necessity of exposing Black flesh he also maintains that there is a power in the invisibility or, more precisely, in the act of not appearing to the “white folk” or, perhaps, to appear to them as completely abject, unrecognizable. That way they should re-start their own horizon of comprehension or, at least, to realize the strange distance that exists between their representations and the others. Du Bois' position is that as long as “White America” desires to keep reproducing the Negro as, in the best of the cases, good it is necessary to create another space through art. This space would be necessarily a collage. Du Bois reflects as following: “We can go on the stage; we can be just as funny as white Americans wish us to be; we can play all the sordid parts that America likes to assign to Negroes; but for anything else there is still small place for us […] They want Uncle Toms, Topsies, good darkies and clowns”[96]

The images above[97], created by Romare Bearden, present an attempt to create this new place for African-Americans. A place that introduces, through the novelty of its composition and texture, a signal or announcement of the internal possibilities of black beauty. Transfiguring the flesh as in “Evening” is a re-birth. The other is really other at the moment that I am seen by him or her. It is the look of the other that surprises us, that puts into question the “I look” and “I said”. But, in birth (“Evening”) it is the blindness or abject look of the woman of the other that destabilizes us, his/her inability to return us a look. Furthermore, it is the presence of all his/her flesh that completely weakens my intention. In birth, it is not me seeing, it is not the other – me – seeing but radically he/she not seeing me. There is that fleshy presence that is not seeing us, but appearing, making place and I just have the intuition that it is the caress that could give us place together without sacrificing her/his otherness and without leaving her/him in the intemperateness.

Birth: inaugurates a new possibility for the senses; the opening of our mother’s body (that in this case is the artwork) is the same opening of worldliness. However, it escapes from us. The densest instance that passes through us does not belong to us; it is always calling us outside our reachable ambit. Birth: a “phénomène saturé”[98], in which the flesh of the other comes to us, as an unexpected donation, with its invisible visibility and infinitude. The concreteness of the presence of the other flesh– and the political responsibilities that this concreteness supposes- does not unveil all the possibilities that are introduced by the new. There is always a rest, the invisibility like in “At the Clef Club”. The invisible/abject brings with it the useless; the absence of product; to overcome the viscosity of the merchandise is an attempt to re-find the true texture of the blood that is combined, in birth, with tears and excrement. The annihilation of the invisible by the hegemony of merchandise or capital leads us to the paths that Du Bois critically referred to above

In its most radical-romantic passages The Souls of Black Folk contains a theory of beauty that is intentionally opposite to the fetishism of money (he called it Mammonism) but it is in itself radically embodied. Du Bois does not oppose fetishism of money to an ideal beauty (as the symmetrical bodies of Augustine[99]); in its foundation Du Bois' notion of beauty is based on the concrete bodies of black people, particularly their “proud body”. For this author body makes reference to a phenomenological wholeness:

We shall hardly induce black men to believe that if their stomachs be full, it matters little about their brains […] Herein the longing of black men must have respect: the rich and bitter depth of their experience, the unknown treasures of their inner life, the strange rendings of nature they have seen, may give the world new points of view and make their loving, living, and doing precious to all human hearts.[100]

Thus, flesh designates a physical, subjective and spiritual materiality that is, to use Du Bois' image, saturated with treasures. The black bodies, for the author or flesh to use our terminology, are permanently transfiguring and presenting themselves in the various textures of their experience. It is important to emphasize that for the author there is not a distinction between body and thought or flesh and soul but an aesthetic of unity. Ethically explained, what is introduced by Du Bois is an ethics of care and self-recognition. By care, a profound respect from oneself and the other must be understood; should be expressed historically through personal and social relationships. Respect functions as criteria of regulation, always that without the respect toward the flesh of the other there is not possibility for an ethic. Economically and politically explained, ethics of care also establish other criteria of regulation. The standpoint of this ethic is the existence of the concrete flesh and the specific dynamics that made its life possible. There are, therefore, conditions of possibility that are unavoidable for this ethic, the first and most important one is the life of the flesh. By this notion is implied, in Du Bois' thought, pleasure, education, access to the best productions of culture and the possibility – freedom- to self- realization through the practices of everyday life. Self-recognition is acquired not through fight or enslavement of the other, but through double movement of destruction and reconstruction. The ethics of care and self-recognition include, as every critical ethic, passing through destruction. This destruction, nevertheless, does not suppose for Du Bois the annihilation of the flesh of the other but disruption of the conditions that are blocking the flourishing of the Beauty of the World.

The images below[101] are just apparently contradictory; both of them are part of the same ethical and political process of the becoming of a new world. Within the “slave ship” and the logic in which it is grounded democracy is impossible. “The Mutiny Aboard the Amistad” is a radical critique – as well as a special form of recollection- of the same roots of Western civilization/Capital production. Making explicit the effective or imagined conflict inside “Amistad” pretends to establish that there is not “freedom” or “post-coloniality” outside the ethical response to the foundational act of violence that inaugurates “our” Modernity. Mutinies are necessary, urgent, and desirable if we want the oceans, our flesh, our dreams freed from “old pirates”. White's “Contribution of the Negro to Democracy in America” includes in itself these two moments or aspects of the process mentioned above. This mural chained the stages of the presence of people of African descent in the United States as an incomplete trajectory that nevertheless is undeniably an announcement from an Angel. As I recalled before, Du Bois' understanding of art is strongly temporal, now it is possible to add that it also contains an ethics of time. In White's mural this ethics of time appears to be expressed in the upper left corner. There an angel is pointing and looking to one side – as the man in “Separation”- in its other hand there is a sword. What is the message of this Angel? What is it looking for and exactly where? What would it do with its sword? Perhaps rather than pointing to the side, the Angel is extending its hand to those who are outside the representation -brown daughters-. The lament of Du Bois is significant for understanding the Angel: “[...] powers of body and mind (of Black Folk) have in the past been strangely wasted, dispersed, or forgotten.[102] To those who have been forgotten the Angel offers its hand and for those who are in the future it offers a sword. The message of the Angel is that there is a possible justice for those that are still waiting for it. This justice, nonetheless, will not be the production of a God or an Angel; it will be a collective creation. What the angel announces is that there is no authentic future when there is absence of ethics toward the past. This includes also an approach to the “present time” and I shall say that the approach is basically interested in the interruption of time's speed.

African-American art does a radical critique of Western modernity and it is expressed in different levels. To summarize I would say that first it rejects a notion of form that identifies Ideal Form with a particular race. Rather, it emphasizes an aspect completely unknown for the “metaphysics of form”, namely the abject. African-American art also makes a gesture which in its lasts consequences is determinant: it returns -recollects – the black flesh as a locus for a re-beginning. In returning to the Black flesh, this artistic expression resists creating a “new essential Negro”; rather, it creates the possibility of even performing the “erasing of the Negro”, as in the case of the woman in “Evening”, erasing his/her positivity, the visibility that annihilates his/her becoming.

Implicitly and explicitly this art also pointed out the relationship between visual representation and Capital production. Perhaps it is through the invisibility of “the Negro” -as in Beardem's art- where this critique reaches its most important expression or, perhaps, also in the abstract art of Samella Lewis, Oliver Jackson or Nanette Carter. The negativity of this art does not appear just through the notion of invisibility but also in the same act of representing black flesh as beautiful. As this could be seen as an essentialist turn it is completely the opposite. What that means is that through art the African- Americans would have the opportunity to have themselves as worth.

§. 4. Last reflection

In this essay I sought to understand or, at least, to postulate some necessary elements in order to grasp the forms that art, Capital production, and racism are related particularly within the context of the United States between 1890-1930. My thesis is that grasping this complex relationship requires an interrogation about the implications of Capital production over the total of social relationships in Modernity. I maintain that Capital production implies a process of rationalization that is articulated with processes of civilization and, more specifically, epistemic constellations.

I focused my discussion on the two concepts that are of basic importance: body consumption and machines with organs. These two concepts allow me to show how racism and Capital production are internally linked. In the realm of this issue, it had been suggested that rather than being a pure biological or natural rhetoric, modernity's racism is grounded on a “metaphysics of form” whose roots could be traced to “beginnings of Western philosophy”. Body consumption is made possible through different means and its rationalization has been intrinsically “flexible”. It was suggested that in order to understand the “commodification of black bodies/machines with organs” it is a basic procedure to interrogate the notions of body that flourishes with Modernity, especially those notions expressed through “expert knowledge”and everyday life visual representations, and their respective context of production.

Especially based on my discussion of W.E.B. Du Bois' analysis of “Negro Art” I proposed an interpretation of African-American art regarding three nuclei: 1) tradition and recollection, 2) beauty and flesh, and 3) ethics of art and recognition. Through each of those nuclei I aimed to prove that both body consumption and the concept machine with organs, as central categories to understand the relationship between visual representation, form, and Capital production, are radically criticized. Of decisive importance in this critique is the notion of flesh that here is related to different traditions. Critically reading Du Bois, I also pointed out important aspects to think about a carnal ethic.

I have introduced this essay with the thesis according to which African-American art expresses a critique of Western Modernity. By critique, it should be understood that what is referred to by the concept of critique is: a) the criteria of regulation, b) the sense of radicalism, and c) its horizon of sense. Hence, critique in the context of this essay refers to a social practice that, based on the desire and necessity of carnal liberation, tries to grasp the social and historical conditions through which social domination is produced and reproduced and struggles for their destruction.

Clearly, there are questions that require further and deeper discussion. Two of those must be mentioned. But before going into those two questions, it is imperative to say that in relation to ethics my discussion functions as a prolegomena. However, that is not, in any sense, a limit but an opening. Art has critical potency and expresses fetishism. In this essay I did not discuss how, for instance, the commodification of art had been affected or limited by the critical possibilities of African-American art. Regarding this issue various questions should be addressed, among others the forms in which the process of commodification juxtapose conceptions of race, gender, and nationality onto African- American art. Along with this discussion, it is necessary to interrogate the project of Du Bois, specifically regarding his notion of race. It is possible to identify limits that still are blocking a more negative assumption of blackness in African-American thinking.

Lastly, it is necessary to read more closely the instances within which expressions of negative subjectivity appear, in order to “organize” a theory of subjectivity from the African-American thinking. What is affirmed here is a theory of subjectivity that needs more, but not less, analysis of particular practices even if they are analyzed in the wide context of Capital production. Of course this project, that is still necessary, includes a complete revision of the trajectories of Capital production and its criticism throughout our societies. In the process of analyzing these trajectories it could be possible to make more precise judgments about the analytical value of concepts that here are not put into question.

Bibliographical references

Adorno, Theodor W. Negative Dialectics. Translated by E.B. Ashton. New York and London: Continuum, 2007.

Anderson, Kevin. Marx at the Margins: On Nationalism, Ethnicity, and Non-Western Societies. Chicago & London: Chicago University Press, 2010.

Arendt, Hanna. The Human Condition. 2nd Edition. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1998.

Bindman, David and Henry Louis Gates, Jr, editors. The Image of the Black in Western Art. Volume III- IV. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2010-2011.

Blackburn, Robin. The American Crucible: Slavery, Emancipation and Human Rights. London-New York: 2011.

Boime, Albert. Representing Blacks in the Nineteenth Century. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990.

Bordieu, Pierre, Méditations pascaliennes. Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1997. Braudel, Fernand. Le Temps du Monde. Paris: Librairie Armand Collin, 1979.

___________. La dynamique du capitalisme. Paris: Arthaud, 1985.

Calo, Mary Ann. Race, Nation, and the Critical Construction of the African-American Artist, 1920-40.Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Carter, J. Kameron. Race: A Theological Account. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Collins, Lisa Gail. The Art of History: African American Women Artists Engage the Past. New Brunswick, New Jersey and London: Rutgers University Press, 2002. Debord, Guy. La Société du Spectacle. Paris: Gallimard, 1992 [1967].

de Gobineau, Arthur.The Inequality of Human Races. Translated by Adrian Collins. New York: Howard Ferting, 1999.

Du Bois, W.E.B. The Soul of Black Folk. New York: Dover Publications, 1994.

____________. Writings. New York: Library of America, 1986.

____________. Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay Toward a History of the Part which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1880. Philadelphia: Albert Saifer Publisher, 1935.

____________. “The Study of the Negro Problems”. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. Vol. 11 (January, 1898): 1-23.

Dussel, Enrique. Encubrimiento del Otro: Hacia el origen del mito de la modernidad. Quito: Ediciones Abya-Yala, 1994.

Elias, Norbert. The Collected Works of Norbert Elias: Essays II: On Civilising Processes, State Formation and National Identity. Dublin: University College Dublin Press, 2008.

Ewen, Stuart & Elizabeth Ewen, Typecasting: On the Arts and Sciences of Human Inequality. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2008.

Fanon, Frantz. Les damnés de la terre. Paris: François Maspero, 1961.

Fleetwood, Nicole R. Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality, and Blackness. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Forti, Simona. “The Biopolitics of Souls: Racism, Nazism, and Plato”. Political Theory Vol. 34, No. 1 (February 2006): 9-32

Harlem Renaissance: Art of Black America. New York: The Studio Museum of Harlem, 1987.

Hartman, Saidiya V. Scenes of Subjugation: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America. New York Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

___________. Lose your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007.

Hegel, G.W.F. Logic from The Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences. Translated by William Wallace. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1873.

Henderson, Carol E. editor. Imagining the Black Female Body: Reconciling Image in Print and Visual Culture. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Jennings, William James. The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2010.

Knorr Cetina, Karin. Epistemic Cultures: How the Sciences make Knowledge. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Lacan, Jacques. Écrits. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1966.

LeFalle-Collins, Lizzetta and Shifra M. Goldman. In the Spirit of Resistance: African-American Modernists and the Mexican Muralist School. New York: The American Federation for Arts, 1996.

Levinas, Emmanuel. Totalité et infini. Paris: Kluwer Academy, 2010.

Lock, Graham and David Murray, editors. The Hearing Eye: Jazz & Blues Influences in African- American Visual Art. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Losurdo, Domenico. Liberalism: A Counter-History. Translated by Gregory Elliot. New York-London: Verso, 2011.

____________. Heidegger and the Ideology of War: Community, Death, and the West. Translated by Marella and Jon Morris. New York: Humanity Books, 2001.

____________. Hegel and the Freedom of Moderns. Translated by Marella and John Morris Durham and London: 2004.

Lukács, Georg, History and Class Consciousness. Translated by Rodney Livingstone. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1971.

Marion, Jean Luc. Le visible et le révéle. Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf, 2005.

Marx, Karl. Grundisse. Translated by Martin Nicolaus. London: Penguin Books, 1993.

__________. Capital Vol. II. Translated by David Fernbach. New York: Penguin Books, 1992.

__________. Capital Vol. 1. Translated by Ben Fowkes. New York: Penguin Books, 1990. Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Œuvres. Paris: Gallimard, 2010.

Mills, Charles W. Blackness Visible: Essays on Philosophy and Race. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1998.

Munford, Clarence J. American Crucible: Black Enslavement, White Capitalism and Imperial Globalization. Trenton, NJ: African World Press, 2009.

Patterson, Orlando. Rituals of Blood: Consequences of Slavery in Two American Centuries.Washington, D.C: Civitas/CounterPoint, 1998.

Postone, Moishe. Time, Labor, and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx's Critical Theory. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Rajan, Kaushik Sunder. Biocapital: The Constitution of Postgenomic Life. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2006.

Robinson, Cedric J. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Chape Hill & London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Rozitchner, León. El terror y la gracia. Buenos Aires: Norma, 2003.

Sallis, John. Transfigurements:On the True Sense of Art. Chicago and London: Chicago University Press, 2008.

Scala, Mark W. editor. Paint Made Flesh. Nashville, Tennessee: First Center for the Visual Arts- Vanderbilt University Press, 2009.

Violi, Alessandra. Le cicatrici del testo: L' immaginario anatomico nelle rappresentazioni della modernità. Bergamo: Edizione Sestante, 1998.

Wallace, Michelle. Invisibility Blues. London-New York: Verso, 2008.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. The Capitalist World-Economy. Cambridge and Paris: Cambridge University Press & Editions de la Maison des Sciences de L'Homme, 1980.

Wilson, Carter A. Racism: From Slavery to Advanced Capitalism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1996.

[1] Master en Teología, investigador y profesor en la Escuela Ecuménica de Ciencias de la Religión, Universidad Nacional. Actualmente realiza un doctorado en la Lutheran School of Theology, Chicago, Estados Unidos. Correo electrónico: jpimentel@una.cr

[2] Willie James Jennings, The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2010).

[3] Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjugation: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (New York-Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

[4] León Rozitchner, El terror y la gracia (Buenos Aires: Norma, 2003), 321. In this essay I distinguish between body and flesh (I also use the concept of souled body/body souled as a relative equivalent to flesh). The notion black bodies is used here to transmit the representation of the various peoples of African origin or descent that was created by and through the expansion of the Western process of Civilization. This notion, which its more precise expression would be in the nineteenth century machine with organs, designates the metaphysical reduction to the produced as other to his/her naked physical phenomenality or its pure carnality understood as lack of reason and predominance of sensuality. This reduction is grounded upon the ontological distinction between body and mind/soul. In this schema the identification with body, flesh or, more precisely, carnality implies a diminution of humanity or the total negation of it for entire populations, groups or persons. Flesh designates a material phenomena that is not reduced to its biological composition or structure. Following Tertullian (animan corporalem et hic) I affirm that flesh is the nucleus of our cognitive abilities (adeo et sine opere et sine effectu cogitatus carnis est actus ) as well as our only possibility to apprehend and experience the World (nihil est incorporale nisi quod non est), our sensuality/carnality is our constitutional being (nihil amare potest sine eo per quod est id quod est ). Apart from flesh -and its actus- there is opening of the World. Theologically reflected flesh is the primordial dwelling of God (adeo caro salutis est cardo). Contrary to Tertullian I do not distinguish between substantia and actus regarding flesh, not at least in its ontological implications. The notion of actus introduces a non deterministic character for flesh that allows, as I will discuss later, a carnal ethics.