Rev. Ciencias Veterinarias, Vol. 37, N° 2, [11-21], E-ISSN: 2215-4507, julio-diciembre, 2019

DOI: https://doi.org/10.15359/rcv.37-2.2

URL: http://www.revistas.una.ac.cr/index.php/veterinaria/index

Disseminated Histoplasmosis in a domestic cat in Costa Rica

Histoplasmosis diseminada en un gato doméstico en Costa Rica

Histoplasmose disseminada em um gato doméstico em Costa Rica

Alejandro Alfaro-Alarcón1 , Alejandra Calderón-Hernández2, Andrea Urbina2, Isabel Hagnauer3

, Alejandra Calderón-Hernández2, Andrea Urbina2, Isabel Hagnauer3

1 Departamento de Patología, Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria, Universidad Nacional, Heredia, Costa Rica. E mail: alejandro.alfaro.alarcon@una.cr

2 Laboratorio de Micología, Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria, Universidad Nacional, Heredia, Costa Rica. E mail: alejandra.calderon.hernandez@una.cr / andreaurbina3@gmail.com

3 Hospital de Especies Menores y Silvestres, Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria, Universidad Nacional, Heredia, Costa Rica. E mail: isabel.hagnauer.barrantes@una.cr

Corresponding author: alejandro.alfaro.alarcon@una.cr

Corresponding author: alejandro.alfaro.alarcon@una.cr

Received: 10/03/2019 Corrected: 07/07/2019 Accepted: 12/07/2019

Abstract: Histoplasmosis occurs occasionally in cats with and without predisposing factors. A 3-year-old domestic male cat was referred to the Small and Wild Animal Hospital at the School of Veterinary Medicine of the National University of Costa Rica with hypothermia, weight loss, anorexia, and progressive chronic bilateral suppurative rhinitis. The patient died during clinical stabilization. A complete necropsy and histopathology were performed revealing granulomatous inflammation with multiple intracellular yeast-like structures compatible with Histoplasma spp. in several organs. Mycological culture of lung tissue was positive for Histoplasma capsulatum. Possible factors involved in this case are discussed.

Keywords: Histoplasma capsulatum; disseminated histoplasmosis; feline; Costa Rica.

Resumen: La histoplasmosis ocurre ocasionalmente en felinos con y sin factores predisponentes. Un gato doméstico macho, de tres años fue referido al Hospital de Especies Menores y Silvestres de la Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria de la Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica con signos de hipotermia, pérdida de peso, anorexia y rinitis supurativa bilateral crónica. El paciente murió durante la estabilización clínica. Se realizó una necropsia completa e histopatología en donde se encontró inflamación granulomatosa con presencia de múltiples estructuras levaduriformes intracelulares compatibles con Histoplasma spp. en varios órganos. Los cultivos micológicos realizados al tejido pulmonar resultaron positivos para Histoplasma capsulatum. Se discuten los posibles factores implicados en este caso.

Palabras clave: Histoplasma capsulatum; histoplasmosis diseminada; felino; Costa Rica.

Resumo: A histoplasmose ocorre, ocasionalmente, em felinos com e sem fatores predisponentes. Um gato doméstico macho, de três anos foi encaminhado ao Hospital de Espécies Menores e Silvestres da Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária da Universidade Nacional da Costa Rica com sinais de hipotermia, perda de peso, anorexia e rinite supurativa bilateral crônica. O paciente morreu durante a estabilização clínica. Foi realizada necropsia completa e histopatologia, onde foi encontrada inflamação granulomatosa com presença de múltiplas estruturas leveduriformes intracelulares compatíveis com Histoplasma spp. em vários órgãos. Os cultivos micológicos realizados no tecido pulmonar foram positivos para Histoplasma capsulatum. Os possíveis fatores envolvidos neste caso são discutidos.

Palavras chave: Histoplasma capsulatum; histoplasmose disseminada; felino; Costa Rica.

Introduction

Histoplasmosis is an infection caused by inhalation of microconidia of the dimorphic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum infecting animals and humans. The fungus is distributed worldwide (Panackal et al. 2002; Mavropoulou et al. 2010; Brilhante et al. 2011) most prevalent in soil containing bird or bat droppings (Kerl 2003; Gingerich & Guptill 2008; Fernández et al. 2011). Histoplasma capsulatum’s conidia could be carried for miles and vertebrates could become infected without being in direct contact with contaminated sites (Colombo et al. 2011). Upon exposure, dogs and cats are equally likely to develop histoplasmosis (Taboada & Grooters 2005). The acute or chronic form of the disease depends on the patient immune status and inoculum (Gingerich & Guptill 2008). Histoplasmosis is characterized by a primary focus in lungs and dissemination to other organs, specially the reticuloendothelial system. Clinical signs include anemia, anorexia, depression, fever, hepatosplenomegaly, lung disease, thrombocytopenia, weight loss and in some cases pancytopenia (Davies & Troy 1996). The infection may be limited to the respiratory system developing subclinical or asymptomatic forms (Kerl 2003; Quinn et al. 2004; Greene 2006). Once the conidia are inhaled and inside the alveoli, they switch to a yeast form inside macrophages and may disseminate to other organs via vascular or lymphatic system (Clinkenbeard et al. 1987; Kerl 2003).

Case presentation

A three-year-old domestic shorthair neutered male cat, with free access to the woods in the area of Cañas, Guanacaste in the northwest part of Costa Rica, was submitted for clinical evaluation to the Small and Wild Animal Hospital of the School of Veterinary Medicine of National University of Costa Rica, due to suppurative rhinitis, anorexia and progressive weight loss for four weeks. The owner reported that five months ago the patient had an episode of bilateral purulent nasal discharge, which responded to antibiotic therapy. Clinical examination revealed poor body condition, hypothermia (36.6 °C), heart rate of 200 beats per minute, jaundice, pulmonary stridor and tachypnoea. Initially, the cat was treated with heat therapy and intravenous fluid therapy (Ringer lactate) supplemented with amino acids, but died before additional diagnostic tests could be performed. Feline Leukemia Virus and Feline immunodeficiency Virus serology were negative.

Post-mortem examination

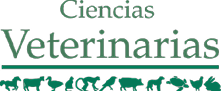

Gross examination revealed poor body condition, yellowish mucous membranes, slightly hemorrhagic pleural and peritoneal effusion. Lungs had multifocal distribution of 5-mm to several-centimeter diameter, multifocal to coalescing, grey-white irregular nodules of granulomatous inflammation (Fig. 1). Mediastinal lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly and mesenteric lymph nodes enlargement were evident. Several tissues were routinely processed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Grocott and PAS stains were used in selected tissue sections. Lung samples were submitted for mycological culture.

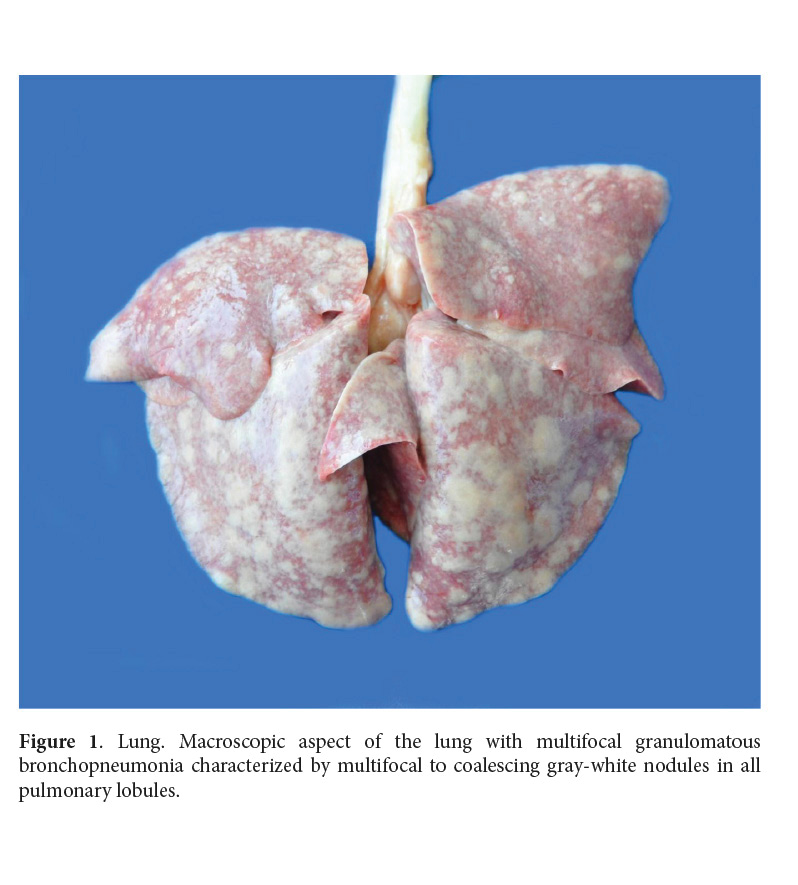

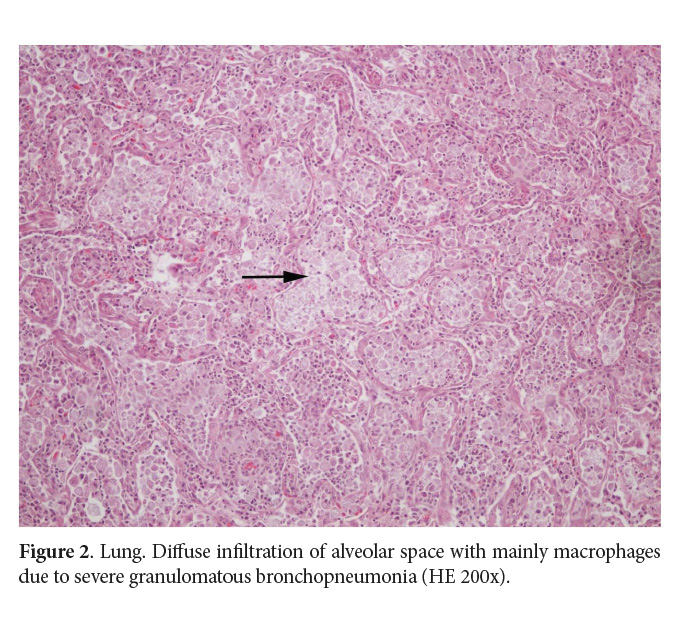

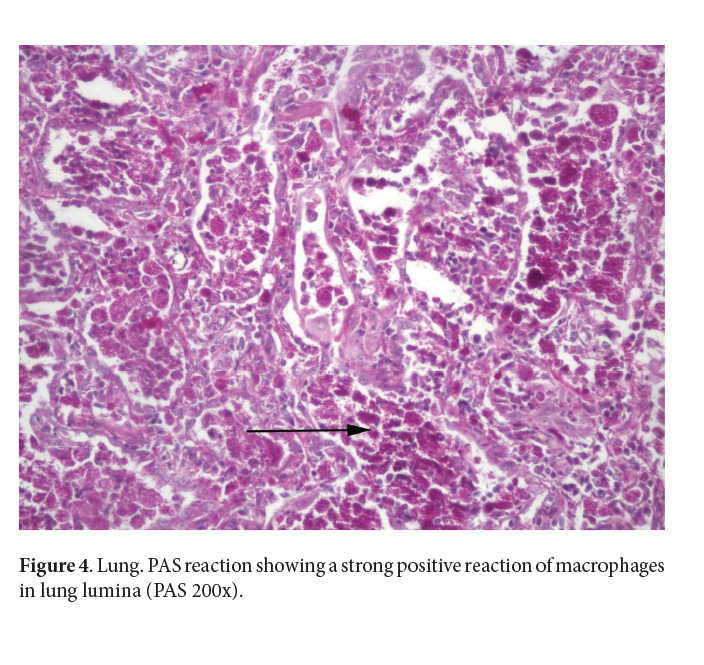

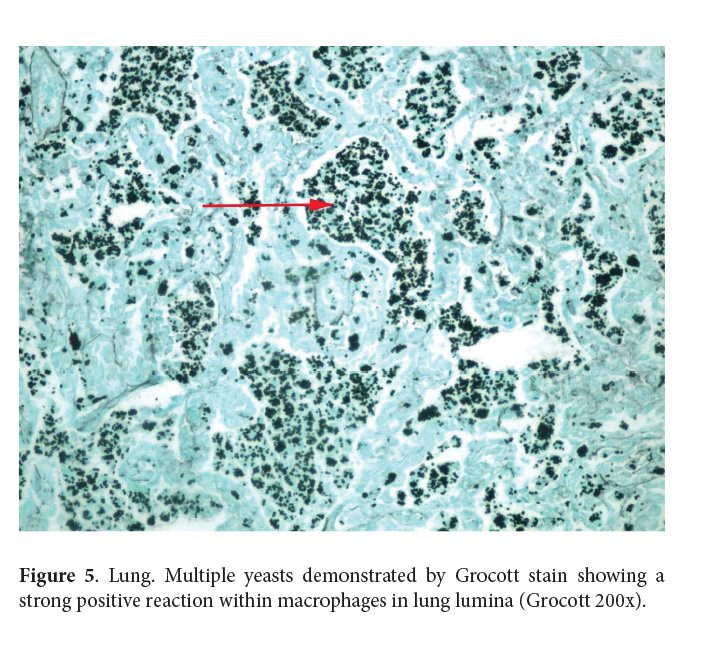

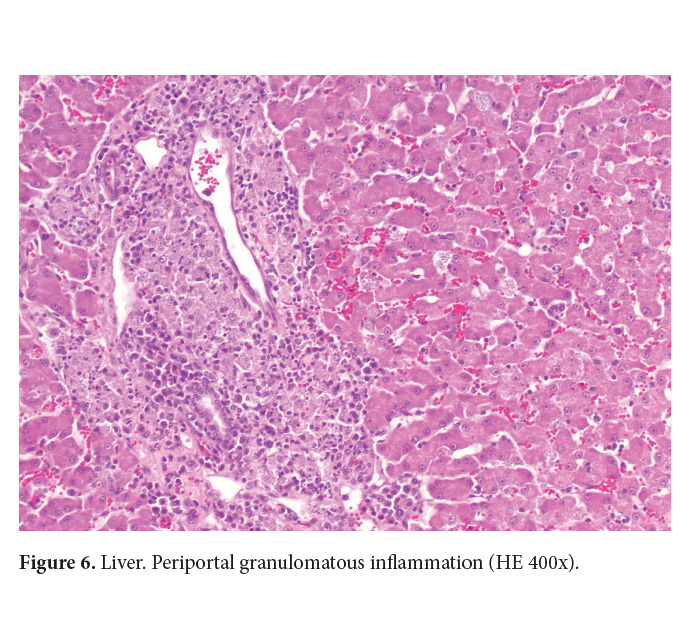

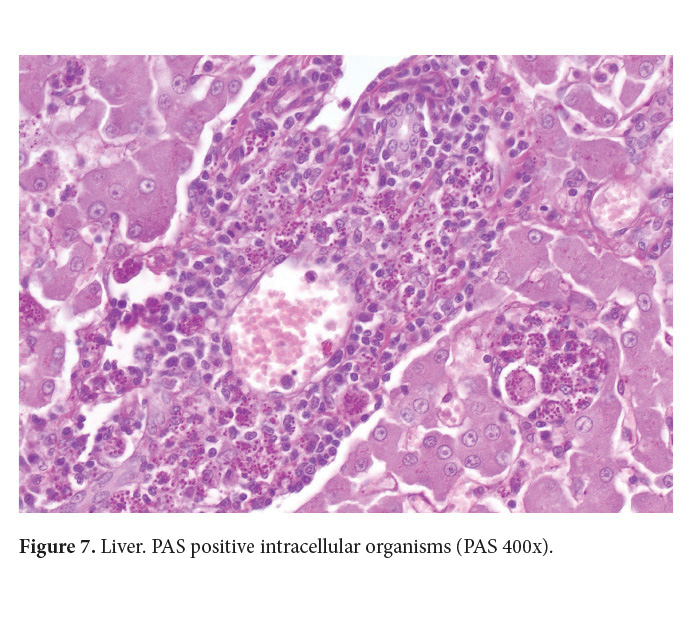

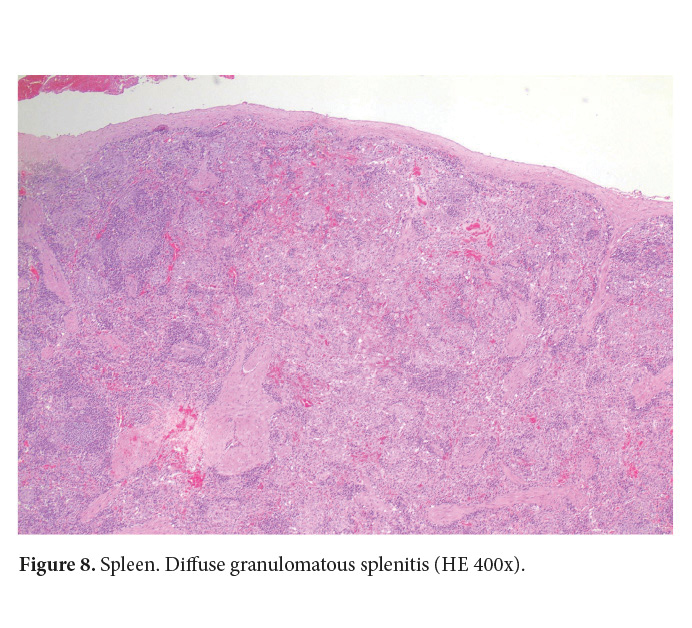

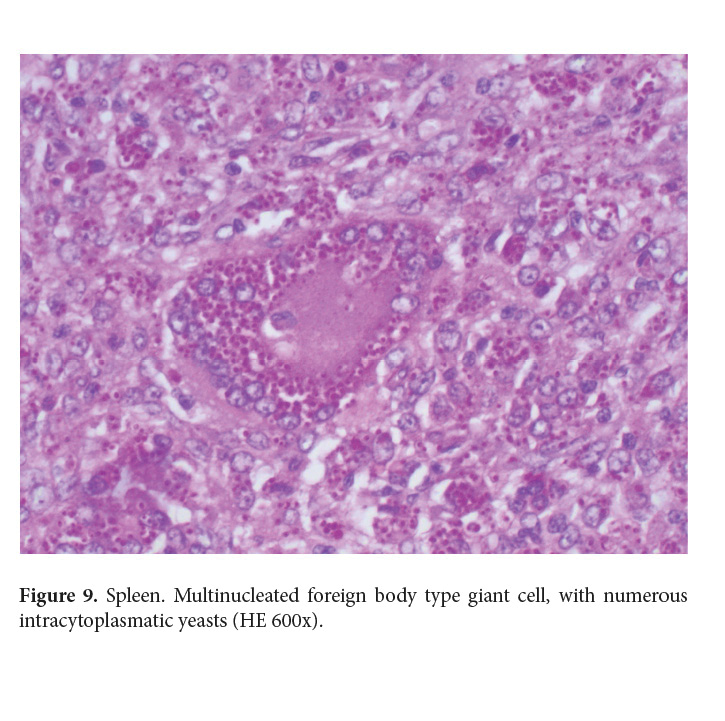

Microscopically, severe granulomatous and necrotizing inflammation was observed in the tracheobronchial and mesenteric lymph node. Lungs presented severe multifocal to coalescing granulomatous bronchointerstitial pneumonia, (Fig. 2). Multifocally, within alveolar lumina there were high numbers of macrophages containing up to 10 cytoplasmic 2x3 µm yeast-like cells characterized by a clear, wide halo surrounding a 1µm basophilic center, (Fig. 3). Liver presented a multifocal granulomatous hepatitis, with single cell necrosis and presence of multiple yeast-like organisms inside macrophages and Kupffer cells (Fig. 6). Grocott and PAS staining of lung and liver revealed numerous yeast-like cells in the cytoplasm of macrophages (Fig. 4, 5 and 7). The spleen had diffuse granulomatous splenitis (Fig. 8 and 9)

Mycological culture

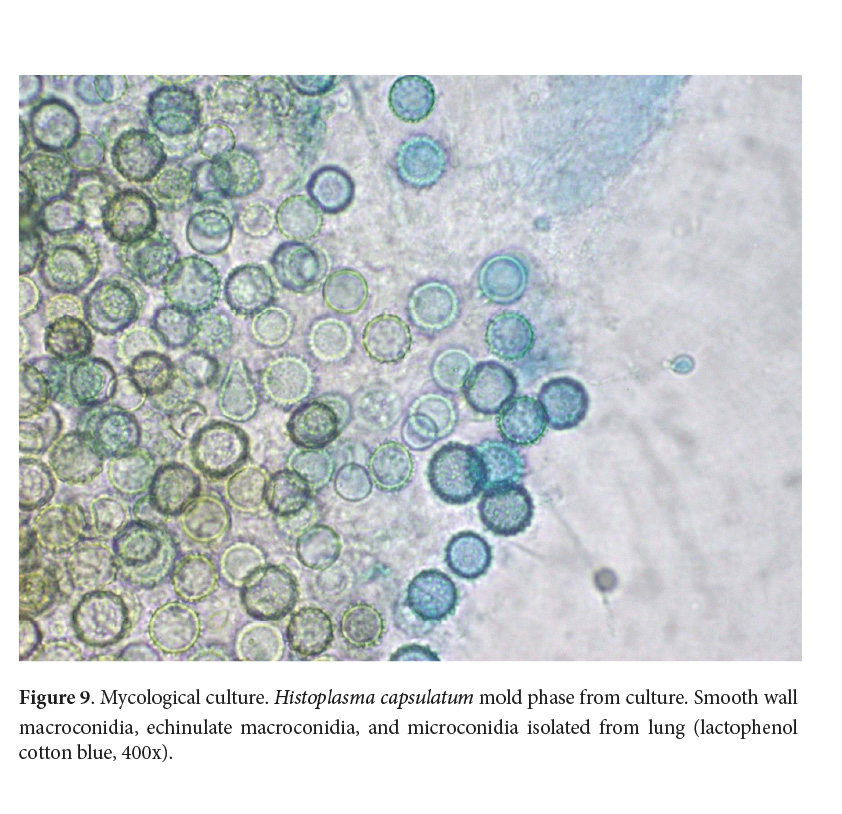

Lung samples were cultured on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar SDA (Oxoid ®, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, UK) and incubated at 28°C. A white filamentous growth was observed in a portion of tissue 22 days later. The fungus was observed with lactophenol blue under light microscopy (Arenas 2003). Thin, long septate filaments, spherical microconidia and smooth and echinulate macroconidia were observed and identified as the saprophytic phase of Histoplasma capsulatum (Fig. 9) (De Hoog et al. 2000; Quinn et al. 2004; Larone 2011). The mold phase was cultured in Brain Heart Infusion Medium (BHI) in order to induce the yeast form in this dimorphic fungus (Quinn et al. 2004).

Discussion

Respiratory and disseminated disease is frequent in feline histoplasmosis, sometimes with nonspecific clinical symptoms (Clinkenbeard et al. 1987; Kerl 2003; Mavropoulou et al. 2010; Lamm et al. 2013; Lloret et al. 2013). It must be differentiated from infections caused by mycobacteria, protozoa and other systemic fungal agents and from neoplasms (Martínez & Revelo 2017).

No predisposing factors were found in the present case and the systemic involvement may be the result of the amount of inhaled conidia (Gingerich & Guptill 2008). Alternatively, the cat could have been suffering immunosuppression due to the stress of being outside its usual environment. This condition may have reactivated a subclinical infection (Klang et al. 2013).

Histopathology is necessary in many cases to support the clinical diagnosis of histoplasmosis, especially when bronchoalveolar cytology is not conclusive. Nevertheless, definitive diagnosis of histoplasmosis is made by culture isolation of the etiological agent from tissuee, body fluid, or organ samples obtained by fine needle (Brömel & Sykes 2005; Arenas 2009). Culture isolation of the etiological agent is considered the gold standard and provides the definitive diagnosis of histoplasmosis (Fernández et al. 2011). Conversion from saprophytic phase to the yeast phase can be achieved by incubating the mold at 37 °C in enriched culture media however, this change was not obtained in the present case. Since the rate of this transformation is low, it is no longer considered a diagnostic tool (Hazar & Hage 2017). Other diagnostic techniques such as serology have been reported as unreliable to identify infected animals since false negatives have been documented (Joseph 2003; Johnson et al. 2004). Histoplasma capsulatum is widely distributed in tropical and subtropical areas and, in Costa Rica human histoplasmosis outbreaks have been reported associated with visits to caves (Lyon et al. 2004). Feline and canine histoplasmosis has been reported sporadically in the Laboratory of Pathology and in the Laboratory of Mycology at the National University of Costa Rica (Alfaro-Alarcón 2013 Unpublished data; Calderón-Hernández & Urbina-Villalobos 2018)). Feline histoplasmosis may occur anywhere in the country especially in areas that meet the conditions for development of this fungus. Systemic fungal infections are often underdiagnosed, mainly because of the nonspecific clinical symptoms. Despite this fact, histoplasmosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of cats and dogs living in endemic areas like our country. From the epidemiological point of view, the confirmation of an animal with histoplasmosis deserves to be investigated since humans may be at risk of acquiring infection from the same environmental source. Although feline histoplasmosis was considered a rare event in the past, it is now accepted that it may occur with the same probability as in dogs (Taboada & Grooters 2005; Greene 2006; Martínez & Revelo 2017). This is the first report of disseminated histoplasmosis in a feline confirmed by histopathology and culture in Costa Rica.

References

Arenas, R. 2003. Histoplasmosis. In: Heras, C. (Ed.). Micología Médica Ilustrada, 2 Edition. McGraw Hill, México, p. 163-172.

Arenas, R. 2009. Histoplasmosis. In: Heras, C. (Ed.). Micología Médica Ilustrada, ٣ Edition. McGraw Hill, México, p. 195.

Brilhante, R.S., Coelho, C.G., Sidrim, J.J., de Lima, R.A., Ribeiro, J.F., de Cordeiro, R.A., Castelo-Branco, D., Gomes, J.M., Simões-Mattos, L., Mattos, M.R., Beserra, H.E., Nogueira, G.Q., de Queiroz Pinheiro, A., & Rocha, M.F. 2011. Feline Histoplasmosis in Brazil: Clinical and Laboratory Aspects and a Comparative Approach of Published Reports. Mycopathologia. 173 (2-3): 193-197. doi: 10.1007/s11046-011-9477-8

Brömel, C. & Sykes, J.E. 2005. Histoplasmosis in dogs and cats. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract. 20 (4): 227–232. doi: 10.1053/j.ctsap.2005.07.003

Calderón-Hernández, A. & Urbina-Villalobos, A. 2018. Veterinary mycosis in a tropical country. 20th Congress of the International Society for Human and Animal Mycology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Abstract, Med. Mycol. 56: S1-S159. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myy036

Colombo, A.L., Tobon, A., Restrepo, A., Quieroz-Tellez, F., & Nucci, M. 2011. Epidemiology of endemic systemic fungal infections in Latin America. Med. Mycol. 49: 785-798. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2011.577821

Clinkenbeard, K.D., Cowell, R.L., & Tyler, R.D. 1987. Disseminated histoplasmosis in cats: 12 cases (1981-1986). J. Am. Vet. Assoc. 190 (11): 1445-1448.

Davies, C. & Troy C.G. 1996. Deep mycotic infections in cats. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 32: 380–391.

De Hoog, G.S., Guarro, J., Gené, J., & Figueras, M.J. 2000. Atlas of clinical fungi, 2nd Edition. Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, The Netherlands/ Universitat Rovira i Virgili Reus, Spain, p. 144, 180-188, 681-682, 755-757.

Fernández, C.M., Illnait, M.T., Martínez G., & Perurena, M.R., Monroy E. 2011. Una actualización acerca de histoplasmosis. Rev. Cubana Med. Trop. 3: 189-205.

Gingerich, K. & Guptill, L. 2008. Canine and feline histoplasmosis: a review of a widespread fungus. J. Vet. Med. 103 (5): 248-260.

Greene, C.E. 2006. Histoplasmosis. In: Greene, C. E. (Ed.). Infectious diseases of the dog and cat, (3rd Ed). Saunders Elsevier, St. Louis, Missouri, p. 577-584.

Hazar, M.M. & Hage, C.A. 2017. Laboratory Diagnostics for Histoplasmosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 55(6):1612-1620. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02430-16

Johnson, L.R., Fry, M.M., Anez, K.L., Proctor, B.M., & Jang, S.S. 2004. Histoplasmosis infection in two cats from California. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 40 (2): 165–169. doi: 10.5326/0400165

Joseph, W.L. 2003. Current diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Trends Microbiol. 11 (10): 488–494. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2003.08.007

Kerl, M.E. 2003. Update on canine and feline fungal diseases. Vet. Clin. North. Am. Small. Anim. Pract. 33 (4): 721–747.

Klang, A., Longaric, I., Spergser, J., Eigelsreiter, S., & Weissenböck H. 2013. Disseminated histoplasmosis in a cat imported from the USA to Austria. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2: 108-112. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2013.04.004. doi: 10.1016/S0195-5616(03)00035-4

Lamm, C.G., Kilburn, J. J., Meinkoth, J.H., & Backues, K.A. 2013. Pathology in practice. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 243 (4): 497–499. doi: 10.2460/javma.243.2.221

Larone, D.H. 2011. Medically important fungi. A guide to identification, 4th Edition. ASM Press, Washington DC, p. 158-159

Lloret, A., Hartmann, K., Pennisi, M.G., Ferrer, L., Addie, D., Belák, S., Boucraut, C., Eqberink, H., Frymus, T., Gruffydd, T., Hosie, M. J., Lutz, H., Marsilio, F., Möstl, K., Radford, A.D., Thiry, E., Truyen, U., & Horzinek, M.C. 2013. Rare systemic mycoses in cats: blastomycosis, histoplasmosis and coccidioidomycosis: ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. J. Feline Med. Surg. 15 (7): 624–627. doi: 10.1177/1098612X13489226

Lyon, G.M., Bravo, A.V., Espina, A., Lindsley, M.D., Gutiérrez, R.E., Rodríguez, I., Corella, A., Carrillo, F., McNeil, M.M., Warnock, D.W., & Hajjeh, R.A. 2004. Histoplasmosis associated with exploring a bat inhabited cave in Costa Rica, 1998-1999. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 70 (4): 438-442.

Martínez, G.E., & Revelo, A.P. 2017. Histoplasmosis en caninos y felinos: signos clínicos, diagnóstico y tratamiento. Analecta Vet. 37(1): 45-58

Mavropoulou, A., Grandi, G., Calvi, L., Passeri, B., Volta, A., Kramer, L.H., & Quintavalla, C. 2010. Disseminated histoplasmosis in a cat. J. Small Anim. Pract. 51: 176–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2010.00866.x

Panackal, A.A., Hajjeh, R.A., Cetron, M.S., & Warnock, D.W. 2002. Fungal infections among returning travelers. Clin Infect Dis. 35 (9): 1088–1095. doi: 10.1086/344061

Quinn, P.J., Carter, M.E., Marney, B., & Carter, G.R. 2004. Mycology. The Dimorphic Fungi. In: Clinical Veterinary Microbiology. Mosby-Elsevier. p. 402-408

Taboada, J. & Grooters, A.M. 2005. Systemic mycoses. In: Ettinger, S. (Ed.). Medicine Diseases of the Dog and Cat Textbook of veterinary internal medicine, (6th Ed). Elsevier Saunders, St. Louis, Missouri, p. 680-682.